Book Reviewed

What a difference the last five years have made to U.S.-Chinese relations! Up until about 2015 it was still possible to talk about “Chimerica,” the word invented by historian Niall Ferguson in 2006 to describe the symbiotic relationship between the U.S. and Chinese economy—responsible, according to Ferguson, for the greatest and most rapid period of wealth creation in human history. Since 2019, however, the same Niall Ferguson has been talking about “Cold War II,” the new, heightened state of economic, political, and military competition between the two countries. Any number of media commentators have tried to blame President Trump and his trade war for worsened relations, but serious observers have seen trouble coming for over a decade. Ferguson himself maintains that the responsibility for Cold War II lies principally with the Chinese themselves, under the ambitious government of Xi Jinping.

How serious is the Chinese threat to the United States, what is the nature of that threat, what are China’s ultimate goals, and what, if anything, should the U.S. do to respond? Michael Auslin and David Goldman tackle those questions in new books, both of which could fairly be called alarmist, though Auslin’s book is the more balanced of the two. Both authors insist that the U.S. is still in a position to contain China’s challenge, but warn that the time to do so is short, and immediate, decisive action will be necessary.

***

Auslin, a research fellow specializing in Asian policy at the Hoover Institution, is by training a historian of Japan. That may in part account for his unusual geopolitical vision in Asia’s New Geopolitics, which aims to see what he calls the “Asiatic Mediterranean” as an “integrated strategic space.” The Asiatic Mediterranean is constituted by the series of “inner seas” running from Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula north of Japan down to Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, and comprising the Sea of Japan, the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea, and the South China Sea. More than 70% of the world’s trade goods pass through these waters, and freedom of navigation is guaranteed in them principally by the United States Navy, in cooperation with naval forces from Japan, Australia, and India.

From the Chinese point of view, however, the islands from Japan to the Philippines and Borneo are the “first island chain” separating China from the Pacific; they are China’s “rimlands” as opposed to its “heartland.” Especially in the South China Sea, China disputes sovereignty over a number of small islands with the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, and Malaysia. Its evident purpose is to contest control of vital navigational routes with the U.S. Navy. In the East China Sea China disputes possession of the Ryukyu Islands with Japan, and it disputes Taiwan’s very right to exist as an independent sovereign nation.

***

In Auslin’s view, America’s strategic goal in the region should be “to ensure that no aggressive power gains control over the Asiatic Mediterranean and thereby threatens the region’s stability.” This policy would require “a combination of maintaining the balance of power and asserting America’s ability to control the waters, skies, and cyber networks of East Asia’s inner seas, if necessary.”

In order to counter China’s challenge, however, Auslin recognizes that the U.S. must make a realistic assessment of China’s overall aims and capacities, and discard some long-standing delusions of American policy elites. The principal delusion—now largely abandoned—was the old Washington Consensus that China’s enrichment would require it to embrace more liberal institutions and make it “a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in the international system.” Few cling to that comforting analysis today. For Auslin, “American policy makers undervalued the resiliency of China’s national interests and the power of the CCP [Chinese Communist Party], misunderstood Chinese history, and underestimated Beijing’s intention to become not merely a leading but a dominant global power.”

The new, more realistic assessment of China requires us to understand what Auslin calls “the New China Rules.” After a concerted effort to develop its soft power following the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, China in recent years has come to the realization that the only way it can win a charm offensive in the developed world, still dominated by liberal democracies, is by discarding its repressive political system. It is clear that under Xi’s leadership China has no intention of allowing that to happen. If there is one thing that the country’s present rulers fear, it is political freedom. What China now seeks to do is to use its astonishing success in economic development and its growing technological prowess to extend its power around the world. The principal strategic means to achieve this goal is the Belt and Road Initiative, which includes a reconstitution of the ancient Silk Road across Central Asia, military and economic cooperation with Central Asian states, a string of naval bases to support its trade across the Indian Ocean and into Africa and the Mediterranean, and the creation of economic colonies in South America, the Caribbean, and elsewhere.

***

In accordance with the New China Rules, the country is building up its armed forces at a tremendous pace, especially its naval and cyberwar capabilities, with the aim of controlling its littoral waters and projecting power into the Indian Ocean. It has exchanged soft power for what has been called “sharp power”: widespread influence campaigns targeting media, politicians, think tanks, and educational institutions as well as industrial espionage and aggressive theft of intellectual property from advanced countries. Scandals such as the arrest of Harvard professor Charles M. Lieber—among the world’s leading nanotechnology experts—dramatized the penetration of China’s policy of “elite capture.” In Australia, the revelation that China had been making massive donations to leading politicians led to legislation there to “limit the influx of third-country influence operations and Chinese funds to officeholders.”

Sharp power abroad is complemented within China by “the smothering of domestic liberal trends and prevention of the further growth of civil society…, all to forestall any domestic liberalization, such as threatened the CCP in 1989.” China uses its economic power abroad ruthlessly to prevent any squeaks of protest making their way into the ears of mainland Chinese. The Marriott Corporation, Mercedes-Benz, the NBA, Hollywood moguls, and many other global corporations have bent to Beijing’s will; those foreign journalists perceived as unfriendly risk deportation. China has raised up as national champions Alibaba, Baidu, Renren, Weibo, and WeChat to defend the Great Firewall against Western invaders such as Google, Facebook, and YouTube. China’s social credit system, though not yet the dystopian nightmare alleged by some Western commentators, will allow the Chinese government far more centralized control over credit scores and financial information than all U.S. credit agencies and the IRS put together, and more alarmingly, is gradually being linked to measures of a citizen’s political loyalty.

Obviously the U.S. and its allies can do little about what happens within China, but how to respond to China’s behavior abroad, and especially in the Asiatic Mediterranean, is a question that policymakers cannot avoid. Auslin is clear, though hardly original, about what U.S. aims should be:

The goal for America remains the same as it has been since 1945—namely, to maintain a balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region while supporting liberal nations that are attempting to create ever more accepted norms and durable links. Such a strategy should not be waylaid by an unwise attempt to contain China, but rather should focus on American strengths and Washington’s deep relationships to create meaningful communities of interest on everything from trade to maritime security. Such will do more to blunt China’s rise than a frantic attempt to counter every move Beijing makes, and this approach is more sustainable for the long run.

***

Auslin’s book is invaluable, however, in describing the current strategic constraints on both China and the U.S., and the two countries’ competitive advantages and disadvantages. He begins from the famous principle first enunciated by Walter Lippmann, that a nation must balance its commitments with its power. The limits of U.S. power mean that it must avoid “interven[ing] in every dispute between Beijing and its neighbors,” while working with allies to prevent Beijing from “unilaterally set[ting] maritime or aerospace rules of conduct or alter[ing] national boundaries, whether through intimidation or force.” America should stop incentivizing disruptive Chinese behavior by ignoring provocations. We should avoid mere diplomatic protests or tit-for-tat complaints about Chinese human rights violations: when China abuses its trading partners, the U.S. should impose concrete economic costs for its bad behavior, by encouraging businesses to reroute supply chains, for example.

The U.S. has long recognized that it cannot continue to project its naval power into East Asia and the Indian Ocean—what the Pentagon now calls the “Indo-Pacific” theater—without help from powerful allies in the region. Of these, Auslin sees the greatest potential in Japan. (The wonderful chapter on Japan, “Japan’s Eightfold Fence,” explaining and defending its “exclusionary nationalism,” is alone worth the price of the book.) It is clear that Auslin has the greatest admiration for Japan’s government and social system, as well he should, and the balance it has managed to strike between modernization and tradition. Against critics who believe that Japan’s development model has been eclipsed by the Chinese economic miracle, Auslin argues that Japan’s embrace of liberal democracy, relative equality, social security, and the rule of law give it real advantages over China in the battle for influence in Asia. “Japan seeks to be loved; China, feared.” China is now the second-largest arms dealer in the world after the United States, and its military sales in Asia have mostly gone to unlovable regimes such as North Korea, Iran, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Burma. Japan, by contrast, is the largest giver of official development assistance in Asia, and its assistance comes with many fewer strings attached than infrastructural assistance coming from China.

***

Though Auslin doesn’t say so, it’s evident that Japan would make a much better leader in any Indo-Pacific coalition to restrain China than the U.S. currently does. Japan has the world’s third-largest economy and has been a global player for decades. It invests more in Southeast Asian infrastructure than either China or the U.S. and far surpasses the U.S. in the provision of foreign direct investment to India. In Asia, as Auslin shows, it has contested control of the region with China for many centuries and knows its adversary well. With the U.S. as its partner and a powerful China as its rival, its neighbors would not have to fear any revival of the Japanese Empire’s “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” of evil memory, any more than Europe now fears German military ambitions.

Japan is also a model for countries across Asia trying to reconcile tradition with modernity. Like Thailand and Malaysia, Japan has a constitutional monarchy that supports a state religion while tolerating religious pluralism. Its Confucian culture links it with Vietnam, Taiwan, and South Korea, and its rich Buddhist traditions create bonds of sympathy in countries with large Buddhist populations such as Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and South Korea. As the dominant power in the region after China, its role in safeguarding the freedom of navigation and international norms of interstate conduct looks far more legitimate to its neighbors than America’s inconsistent activities as the world’s policeman. It doesn’t engage in ideological hectoring the way both China and the U.S. do. In short, Japan has more strategic credibility than the United States in the Indo-Pacific and is better positioned to take the principal role in any alliance to contain China.

A major obstacle to this line of thought is the self-important belief of many in our foreign policy establishment that only the U.S. can and should take the lead in any coalition against totalitarian threats. We still take it for granted that our president is the “leader of the free world.” Still wrapped in our fading national myths, we have difficulty comprehending how the U.S. has been hemorrhaging influence within Asia in recent years. Soft-power experts blamed President Trump’s “America First” policies for its reputational decline, but under the new Biden Administration, the slide is likely to continue.

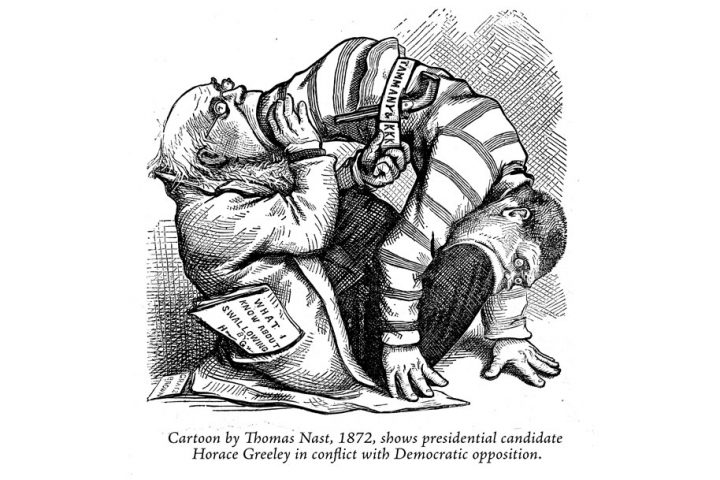

American political life has become hyperpartisan and dysfunctional. We are no longer the poster boy for liberal democracy. Meanwhile, our educated elites have largely abandoned their country’s traditional advocacy of free speech, free exercise of religion, and private property. Woke leftists embedded in universities, large corporations, and professional societies are now determined to brand our country as “structurally racist,” offering up declarations of guilt that CCP propagandists have seized upon with glee. They are bent on establishing a form of ideological tyranny that resembles Mao’s Cultural Revolution, which even the CCP has repudiated. In that context, to deploy the standard U.S. weapon of attacking China for its violations of human rights will hardly seem other than absurdly hypocritical. The Left and the Democratic Party can be counted on to continue their assaults on capitalism—an aspect of American culture genuinely admired by Asians—and to advocate radical experiments in sexuality and family life—a side of American culture that the vast majority of Asians find embarrassing or repulsive.

Edmund Burke famously wrote, “[t]o make us love our country, our country ought to be lovely.” The same applies to relations between countries. The U.S. is becoming increasingly unlovely on the world stage, and in Asia the audience is not loving it. Progressive ideology may be attractive to many Europeans, but it is far less so in Asian countries, which have much more recent and positive experiences of economic freedom and are generally more conservative in their social norms. If the U.S. wants to exercise real leadership in East and South Asia—moral leadership—we need to recover belief in our own traditions of ordered liberty, free enterprise, and civic virtue. Otherwise U.S. leadership amounts to little more than a large bank account, some aircraft carrier battle groups, and a matchless ability to eavesdrop on other nations.

***

Auslin’s book is a must-read for anyone interested in the question of how the U.S. can respond to China’s ambitions to dominate East and South Asia. I have more reservations about David Goldman’s book, though there is much to be learned from it. As a former investment banker with wide experience in China over several decades, Goldman acquired an intimate view of Huawei’s operations and was among the first to realize the wider implications of its 5G capabilities. He has been, as he writes, “inside the belly of the dragon.” Like many others I profited from reading his columns in the Asia Times, written under the pseudonym “Spengler,” which offered sharp insights into Chinese business practices and technology, and their links to Beijing’s strategic objectives. But the virtues of an opinion columnist do not necessarily appear to advantage in the longer format of a monograph. You Will Be Assimilated is a series of firecrackers deployed in chapters assembled from op-ed columns, long-form journalism, interviews, and oral presentations. Goldman’s stock-in-trade is strong, attention-getting claims and myth-busting, eked out with mounds of statistics and streams of anecdotes, many of them entertaining and instructive. A sense of his manner is given by the title of the book’s introduction, “Everything You’ve Heard about China is Wrong (Or Not Right Enough).”

Goldman’s principal objective in the book is to focus attention on “China’s plan for global economic supremacy.” He has a banker’s view of the Belt and Road Initiative and a financier’s understanding of China’s capital markets and the deceptive way China deploys infrastructural aid to developing countries—what has been called its “debt-trap diplomacy.” Both are informative perspectives, to be sure. He is less cogent in his analysis of Chinese education and military capacities. It is true that China graduates six times as many engineers as the U.S., but the quality of its STEM education can be uneven. China has an amazing capacity to build roads, bridges, high-speed rail lines, universities, and even whole cities in short periods of time. You need a lot of engineers to do all that. But for high-tech engineering and especially biotech and nanotechnology, China is still very much dependent on Western talent and innovation. Huawei has succeeded in its quest for 5G dominance only by hiring tens of thousands of Western engineers.

***

Huawei is the central exhibit in Goldman’s presentation of China’s economic threat. He gives some illuminating examples of how 5G is being used to transform robotics and industrial design, and how it was deployed effectively—though with massive invasions of privacy—to track and trace the coronavirus. He predicts that 5G will take away within a few years the U.S.’s longstanding advantages in “SIGINT,” its ability to eavesdrop on other countries via electronic networks.

Goldman agrees with some other analysts that 5G is so important that the economic disruption it will cause will amount to a Fourth Industrial Revolution. The Anglosphere created the first three industrial revolutions (steam, electric, and digital), but China is creating the fourth, which will give it the power to dominate the world economically. The U.S. cannot allow this to happen, Goldman writes. His solution is for the government to invest vastly more resources in research and development than it has hitherto, to build out its own national champions in quantum computing, big data, and 5G networks. Huawei’s 5G advantage is the new Sputnik, and we need at least the equivalent of NASA to counter the new technology.

For Goldman, America’s genius for innovation still gives us an advantage over China. We should use that advantage to create “game-changing break-throughs.” His argument here is that we cannot rely on the free market, with its “small ball” profit incentives, to produce the kinds of major innovations we need. We need the government to back “long ball” projects, as it did in the cases of the nuclear arms race, the space race, and the internet. The Chinese use the same argument to explain why their system of state-controlled industries is superior to Western free market capitalism.

Goldman dismisses, however, the idea that China presents an ideological challenge to America. “There are more Marxists in Cambridge, Massachusetts, than in the whole of China,” he quips. China’s economic challenge to the U.S. is a straightforward power play, he maintains, and the CCP does not aim to impose its ideology on the rest of the world, as the Soviet Union sought to do in the Cold War. This is far too glib. Some elements of the Chinese elite are certainly aware that its political system doesn’t have wide appeal. China’s leading political theorist, Yan Xuetong, recently warned the CCP leadership that it would be unlikely to profit from its current attempts to ramp up ideological debate with the United States. Yet China certainly understands that its track record of rapidly increasing its own wealth and influence, educational levels, and military power while maintaining authoritarian government will be attractive to many Middle Eastern monarchies, African dictatorships, and former Communist regimes. Development models always have an element of ideology, and Mao’s image remains on every banknote issued.

***

Goldman’s reading of China’s objectives in Cold War II is shaped by his tendentious understanding of Chinese history. One of his ideas, for example, is that China in the past generation has escaped a “tragic cycle” which kept its attention directed inward, and is now for the first time economically secure enough to turn its attention outward, to world conquest. Most historians of China, by contrast, see its long history as a series of expansionist and isolationist episodes. If its economic health was precarious before recent times, so was that of every other nation before the First Industrial Revolution. Until around 1800, most individuals in the world lived on one or two dollars a day. China experienced many invasions, civil wars, and changes of dynasty over its 3,000 (not 5,000) years of recorded history, but for much of that time it was far more prosperous, peaceful, and technologically advanced than Western societies were between the fall of the Roman Empire and the 19th century.

A more serious misreading of Chinese history is Goldman’s take on imperial China’s political principles, which he believes still inform the CCP’s outlook and policies. A historian of China would call these principles Legalism. Legalism is not about the rule of law in the modern Western sense, as the name might imply. As a school of political thought and practice it might better be labeled authoritarianism or political realism. It has often been compared to Machiavellianism. It was born in the Qin dynasty, a period of total war, as a strategy for producing a “rich state and a powerful army,” as Sheng Yang, prime minister of the Qin in the 4th century B.C., put it. This meant maximizing the coercive power of the state and subordinating all of economic, cultural, and intellectual life to that one aim.

Goldman sees all of Chinese imperial and modern history as driven by the Legalism of the Qin dynasty; for him origins are destiny. The problem with this view is that the Qin lasted only 15 years, from 221 to 206 B.C., and its rapid collapse, as all later Chinese historians agreed, was precisely due to its reliance on a hateful political philosophy that failed to secure willing obedience from the people—the basis of all enduring government. China’s embrace of Confucian political philosophy in the subsequent Han dynasty was the direct result of Legalism’s failure. There have been some attempts in the recent historiography to argue for the continuing, subterraneous importance of Legalism in Chinese imperial history, but the fundamental fact is that the ruling political philosophy of the Chinese empire from the Han dynasty, contemporaneous with the Roman Empire, until 1911 was Confucian.

***

The Confucian approach to foreign relations was, and is, a deeply moral one which rejects predatory state behavior as un-Chinese and inhumane. Confucian ethical and political thought has been powerfully revived in the contemporary Chinese academy as well as in its wider society, and it is contesting the revived Legalism of Mao Zedong and the older generation of party leaders. It has made inroads even at the Central Party School and among younger members in the CCP leadership. China’s first Legalist dynasty lasted 15 years; the second, Maoist one, has already lasted over 70. How much longer can it go on without reform?

What’s more, it has by no means been lost on the Chinese that their attempts to exercise influence abroad have been crippled by the Legalist features of their foreign policy: its secrecy and duplicity, its “sharp power” attacks on its trading partners, its military threats to its neighbors, its hatred of political freedom, its attacks on privacy and religious life. Goldman is certain that China is destined to rule the world unless the U.S. engages in vigorous efforts to stop it. But other views are possible. It may well be that China is one foreign policy disaster away from a transition to a more humane form of government.

Given his jaundiced view of Chinese history and culture, Goldman is unwilling to entertain the possibility that China might have a better future. This prejudice extends also to his view of the Chinese people in general. He says he’s “not a panda-hugger,” and that’s an understatement. For him, the Chinese people are willing partners in the evils of the CCP regime. “The character of China’s government corresponds to the character of its people,” he asserts. In his portrayal, they are a cruel people—pagan, pragmatic, and materialistic. “[T]he Chinese are probably the least spiritual people in the world.” “Cruelty is the norm in Chinese governance.” It is a “ruthless meritocracy” where friendship hardly exists and affective relations are confined to the family. But even Chinese families, according to Goldman, are vitiated by “amoral familism,” which makes them function like the mafia. There is no possibility that China might liberalize, since, lacking the Judeo-Christian concept of human dignity, it has no respect for individuals. “There’s no sense of rights and obligations as we have under Roman law”—a truly absurd statement in view of the deep impress that Confucian ethics (similar in some ways to Stoicism) still has on the modern Chinese character.

***

I have to wonder about the sort of Chinese people Goldman has met in his life over the past few decades. I have been teaching Chinese students for 30 years, and have found them in general to be friendly, modest, decent, respectful of their teachers, extremely hard-working, and eager to learn. I wish I could say the same of all my American students. In any event, if someone were to say the kind of things about Jews that Goldman says about the Chinese, he would be accused of anti-Semitism.

Although Goldman is surely right in his larger judgment that China is not about to evolve into a Western-style liberal democracy, there may be a middle way. Its most liberal political theorists hope for a kind of hybrid regime, mixing local democracy with a re-moralized meritocracy at the higher levels of its central administration. They advocate a revival of Confucian tianxia, a model of international order in which a Middle Kingdom acts as a source of power and civilized values and allies itself with sympathetic states at its periphery against yi or barbaric states. Much of the demonization of China in the West comes from the misguided view that, since we no longer think China will become like us, it can only remain a totalitarian Communist country, an enemy state implacably opposed to humane values. While one cannot but agree that China’s actions internally sometimes deserve condemnation and its behavior abroad sometimes requires energetic containment on the part of America and its allies, we need to be aware that this great and ancient country harbors other visions for its future.