Book Reviewed

In Republic of Wrath, Brown University political scientist James Morone tries to explain the political distemper of our times. To Morone, “Who are we?” has been the central question of American politics since the beginning, when worries over immigrants in the 1790s led a Federalist Congress to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts. Race is a mainstay of his account, too; the book opens with a barely-averted slave rebellion in Richmond on the eve of the 1800 election.

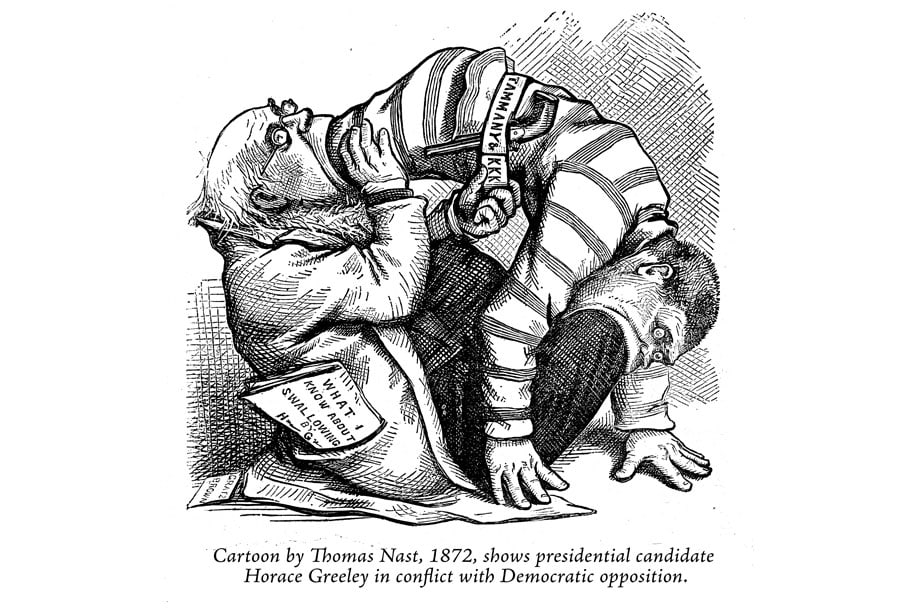

Despite his wide sweep, Morone focuses his attention on moments or eras that, in his view, best capture the dominant tendencies of American politics: the elections of 1800 and 1840, the Civil War and Reconstruction, the populist movement of the late 19th century, the New Deal, the election of 1964 and its immediate aftermath, and the modern era from 1968 to the present.

He identifies two long-term patterns which, he believes, have shaped party competition and political discourse. One is that white supremacy has been consistently linked with doctrines of limited government. The other, more original claim is that blacks and immigrants have usually had opposing partisan patrons. In the 19th century, Democrats took up the cause of immigrants, while Whigs and Republicans were more sympathetic to the rights of blacks. What makes the current era so incendiary, Morone argues, is that for the first time in American history, one party is favorable to both immigrants and blacks (Democrats, if you’re wondering) and the other party (Republicans) is hostile to both. Our politics are, as a result, more “tribal” than ever. (One wonders if Morone is inviting cancellation for use of this term.)

***

Republic of Wrath is not without its merits. For one thing, it is engagingly written. For another, though it’s not exhaustive, it covers a lot of ground. In doing so, Morone puts a spotlight on a great many interesting tidbits, including the domestic impact of the Haitian slave revolt and the trade treaty signed by the John Adams Administration with its leader, Toussaint Louverture; the (likely) true details of William Henry Harrison’s untimely demise (contaminated water from an open sewer near the White House); and the story of Robert Smalls, the escaped slave who stole a Confederate steamer, sailed it to freedom, and later became a U.S. congressman. Not least, Republic of Wrath is full of salutary reminders that sharp partisan conflict—even conflict the antagonists see as politically existential—is a thread that runs throughout U.S. history.

Morone is clearly a man of the Left, and tells his story from that perspective. Yet he resists the temptation, which seems particularly strong in our day, to make sweeping and ungenerous assessments about conservatives as a whole. “Democrats vastly oversimplify,” he argues,

when they tag Republicans as a band of racists. Many conservatives are baffled to hear their party denounced that way…. [Many Republicans] have their gaze fixed on entirely more honorable matters: less government, lower taxes, fewer regulations, religion, patriotism, the military, protection for the traditional family. And above all, a philosophy of leaving people alone.

His argument, instead, is that honest conservatism has become tainted by association with racists who became part of the Republican coalition in 1964. To a degree, this criticism has already been accepted by a number of conservatives themselves, including Newt Gingrich, who back in the 1990s repented of Barry Goldwater’s vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (even though Goldwater voted on constitutional, not racist, grounds).

***

Nevertheless, the gist of Morone’s story is open to criticism on a number of fronts. First, the association of white supremacy with limited government is not as clear as he thinks. True enough, 19th-century Democrats were both the party of white supremacy and the party of strict construction, right up until Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)—when they jettisoned the latter, and shortly took up arms against limited, constitutional government. And what about Martin Van Buren? Morone notes that Van Buren was the first president to use the word “slavery” in an inaugural address (1837), but fails to mention that he later bolted the Democratic Party in order to run as the presidential nominee of the Free Soil Party in 1848, without in the least abandoning his limited government principles.

The connection becomes even less obvious in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. White supremacy ultimately joined forces with populism in the South. Morone notes the crude racial views of Georgia’s Tom Watson and South Carolina’s Ben Tillman without ever mentioning that both were populist Democrats. The Jim Crow South was Woodrow Wilson’s electoral bulwark, and Morone lightly glides over the fact that Wilson was not only a racist and ardent segregationist but a big-government progressive, leading a movement that had declared natural rights, separation of powers, and a restrained executive passé. And, of course, the South was largely happy with New Deal activism until it began inching toward civil rights and the importation of aggressive labor unions into the region. Whatever constitutional sentiments issued from the mouths of Southern orators, the solid South served as the reliable electoral foundation for Progressive and liberal policymaking.

***

Morone’s treatment of the modern era suffers similarly from the attempt to fit the facts into an overly simplified narrative. For example, although the deep South voted for Goldwater in 1964, the outer South (Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, Florida, and Texas), which had started voting Republican for president in the 1950s, went for Lyndon Johnson in 1964. In 1968, the deep South voted for George Wallace, most of the outer South for Richard Nixon, except for Texas, which voted for Hubert Humphrey. After the Nixon blowout of 1972 when virtually the whole country voted Republican, Jimmy Carter won most of the South in 1976. In 1980, the Reagan campaign initially assumed the deep South would stick with favorite son Carter, and focused on the Midwest. Only when polling showed promise late in the campaign did resources shift. Reagan ultimately won deep South states Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas by a whisker. The South didn’t become solidly Republican territory in presidential elections until the late ’80s.

The same could not be said of congressional elections until 1994, three decades after Goldwater and the Civil Rights Act. As Morone acknowledges, with a few notable exceptions, the Southern Democratic officeholders who had upheld segregation did not become Republicans; they retired and were replaced by Republicans, sometimes with another Democrat in between.

Morone’s emphasis on the persistence of white supremacy obscures all such nuance, and doesn’t do justice to the enormous changes in American attitudes toward race since 1950, even in the South. Neither does the rise of Donald Trump fit neatly into the thesis of Republic of Wrath. Morone repeats the standard trope that Trump’s 2016 victory was driven by “racial resentment,” as measured in surveys. A closer look reveals that the questions often measured not animus against blacks but resentment of perceived racial double standards. In any case, Morone forgets to mention that it was the voters in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ohio who voted for Trump, after having voted for Obama twice, that made the difference in 2016.

Republic of Wrath concludes with advice for Democrats, Republicans, and the country as a whole. James Morone’s advice to Republicans is not half bad: take your message directly to Asians, Hispanics, and African Americans. “There are plenty of connections between the conservative message and each of these groups,” he notes. In 2020, Trump took that advice and increased his share of each voting group, and the surprising Republican gains in the House were built on the same strategy. That might not have been the author’s preferred outcome.