Book Reviewed

In 1996 Bob Woodward embarrassed First Lady Hillary Clinton by revealing that she had attempted to commune with the ghost of Eleanor Roosevelt during a session with a spiritualist in the White House solarium. Mrs. Clinton explained that her “conversation” with Mrs. Roosevelt served no occult purposes but was merely a psychological exercise to put herself in the mind of the only presidential wife in history more hated than Clinton herself. During her 2000 campaign for a U.S. Senate seat from New York, Mrs. Clinton appealed to her predecessor again. Mrs. Roosevelt had briefly considered running for a Senate seat from New York in 1945 after her husband’s death. Hillary hinted that her own election would redeem that missed opportunity and ratify Eleanor’s legacy.

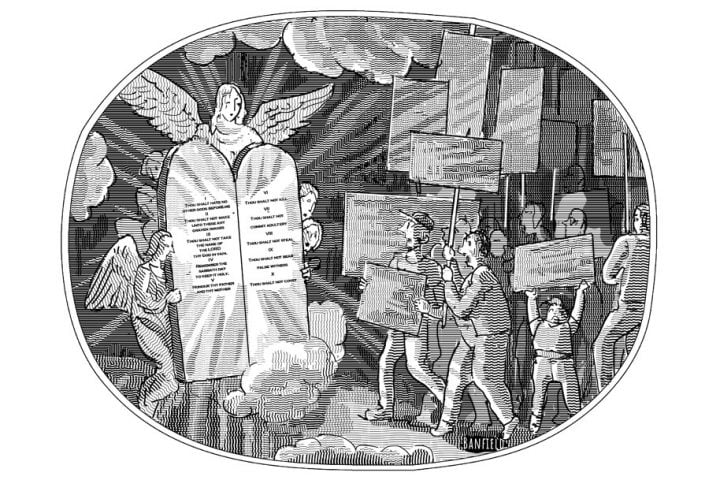

The irony of Eleanor Roosevelt, feminist political icon, is that her career was a 50-year vindication of every misogynist cliché about women in politics. Her politics were sentimental rather than rational. She was impulsive and easily swayed, a busybody who meddled in every issue under the sun without bothering to master anything intellectually. She honestly believed we could end poverty and war by all being a little nicer to each other. Hillary at least has a political temperament. Eleanor, had she not married Franklin Delano Roosevelt, probably never would have gone near politics at all.

***

How did a person so unsuited to the political life become the most admired woman in America and “First Lady of the World,” as Harry Truman dubbed her? David Michaelis, biographer of cartoonist Charles Schulz and illustrator N.C. Wyeth, tells the story without ever quite solving the enigma. In the end, the most we can say is that Eleanor was the opposite of her husband. The lesson of FDR’s life was the power of character to overcome unfavorable circumstances. The lesson of Eleanor’s was the power of circumstances to make a heroine out of the most unpromising character.

The place to start is with her face. The bovine eyes, the vanishing chin, the buck teeth, those jowls. During the fight over women’s suffrage, anti-suffragists claimed that only ugly women were interested in politics, to compensate for their inability to find happiness through normal channels. A cruel and baseless generalization, no doubt, but certainly in Eleanor they had their most glaring data point since the Quaker sisters and abolitionists Angelina and Sarah Grimké.

Perhaps it was a blessing that she was homely, otherwise her ferocious desire to be loved could have sent her down the road of her Aunt Edith “Pussie” Hall, whose romantic disasters were the inspiration for Lily Bart in Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth. Eleanor was the daughter of an alcoholic, and like many children in that situation she strove to be ever more doting and selfless in the hope that one day her father would love her enough to stop drinking. Alas, Elliott Roosevelt pursued self-destruction with the same fixity and determination that his brother Theodore brought to progressive politics. He died at 34 after leaping from his mistress’s window in a drunken fit. Nine-year-old Eleanor was not permitted to attend the funeral, for fear she would encounter her father’s lowlife gambling associates or her illegitimate half-brother.

***

The passion for self-abnegation that she developed trying to rescue her father eventually led her to her fifth cousin once removed, Franklin, another glib charmer whose emotional default was to take and take without giving back. No historian has ever satisfactorily explained what Franklin saw in Eleanor, but for her part, she had another man to please. Michaelis tells the story of how Eleanor nursed Franklin through a bout of typhoid fever in 1912, carrying his trays and dispensing his medicine, until her mother-in-law came for a visit and noticed that Eleanor herself was radiating heat. The doctor took her temperature and found a fever of 104. She’d had typhoid for two weeks. To be uncomplaining was Eleanor’s greatest joy in life.

Some women not blessed with good looks go in search of an alternative source of charm and find it in cultivating their intellect or in a life of good deeds. That is not quite what Eleanor did. Politics was not her way of trying to get people to like her. She long ago had decided that the only way for a charmless girl like her to be happy was not to care whether people liked her or not. This indifference, combined with her position as the wife of a powerful politician, meant that people were constantly asking for her help with some scheme or another and she was constantly saying yes, without worrying that she might embarrass herself or her husband. That was how Eleanor blundered into a political career of her own, almost by accident.

Consider her first major political project as first lady, the Arthurdale development in West Virginia. Eleanor was moved by the desperate plight of out-of-work miners and, because they lived so close to Washington, it was convenient to throw herself into the effort to help them. She insisted that their housing include modern amenities like indoor plumbing and refrigeration, even though that put the homesteads far beyond what the beneficiaries could afford. She tried to have a furniture factory built in Arthurdale, not realizing that subsidizing new competition in the middle of a depression would not sit well with existing furniture makers. By the end of the decade, no factory had been built, most Arthurdale residents were still on welfare, and the unit cost of their homes had risen to $16,635, up from an original target of $2,000. “My Missus, unlike most women, hasn’t any sense about money at all,” FDR shrugged.

***

Her inability to graduate from sentimentality to principle meant that Eleanor was easily blown hither and yon by the gust of events. When Neville Chamberlain signed the peace deal at Munich, she applauded as a pacifist. When her husband advocated war against Hitler, she applauded as a humanitarian, with no sense of inconsistency. Even on the issue for which she was most famous, the rights of African Americans, her strength as an advocate came not so much from passion as from simple-mindedness. This was helpful when it came to asking why black contralto Marian Anderson couldn’t sing for anyone who wanted to hear her in 1939. But when Brown v. Board of Education was handed down in 1954, her “My Day” column on the ruling was almost insipid:

Southerners always bring up the question of marriage between the races, and I realize that that is the question of real concern to people. But it seems to me a very personal question which must be settled by family environment and by the development of the cultural and social patterns within a country. One can no longer lay down rules as to what individuals will do in any area of their lives in a world that is changing as fast as ours is changing today.

This compulsion to find the good in both sides made Eleanor worse than useless during the Cold War. Her naïveté in the face of Communism was staggering. As far back as the New Deal, her idea of vetting the American Youth Congress was just to ask them. “I told them that since I was actively helping them, I must know exactly where they stood politically…. In every case they said they had no connection with the communists.” (Believe it or not, some of them were lying.) Later, during her “First Lady of the World” phase, she reasoned that the way to win the Cold War was simply to outcompete the Communists for hearts and minds: “[T]here are good things in the Soviet world and we should give them credit for these. Then, on our own initiative, we should develop a program that we believe will be of greater advantage to the newly developing nations of the world.”

***

Considering that she had no knack for it, it is tragic that Eleanor should have sacrificed every other sphere of life to politics, but she did. She was a notoriously bad dresser, bad hostess, bad housekeeper. The White House kitchen served hot dogs and peanut butter sandwiches while she was First Lady, to Franklin’s chronic dismay. Nor did she devote much energy to raising their children, leaving that to her mother-in-law and the servants. The American people held this against her when the Roosevelt brood grew up to be feckless and scandal-prone, with 14 divorces among them. If Eleanor had not been off do-gooding, they reasoned, she might have been a better mother.

As the decades rolled on, Eleanor grew further out of touch with the mainstream of liberalism. She did not care for rock and roll (“I have found that stirring up pure emotion with very little reason behind it is never a very good thing for young or old”) and thought John F. Kennedy a step down from Adlai Stevenson. Still, the sheer longevity of her career, and the talismanic power of her surname, made her a pillar of Democratic politics well into the 1960s, particularly in New York State. She did not have to do much; it was enough for her simply to be there. Looking over Michaelis’s sympathetic survey of her long life, one gets the sense that was always the secret of Eleanor’s success. She was not more intelligent, or public-spirited, or kind-hearted than other women of her class. She was simply in the right place at the right time with the right name.