Book Reviewed

The Library of America’s anthology of conservative writing shares the idiosyncrasies of its editor. Andrew Bacevich is a citizen-soldier-scholar with a long history of publishing in conservative periodicals. He is also, by his own lights, a conservative. But he is a conservative in opposition to other conservatives, and the chief influences on his mature thought have been the progressive historians Charles Beard and William Appleman Williams, along with the liberal theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Bacevich is trenchantly critical of U.S. foreign policy, but he is neither a libertarian non-interventionist nor a paleoconservative America Firster. He is rather a modern exemplar of anti-war progressivism.

He has assembled an excellent collection in American Conservatism. But it is in effect a progressive’s selection of the best of the American Right, fortified with several items from out-and-out socialists or Left liberals who make arguments with which the editor sympathizes. These items are, for the most part, invigorating reading in their own right. They are also, however, an admission of defeat: Bacevich has failed to find within the conservative tradition itself, even as broadly defined as it is in these pages, sufficient material to support his own principles.

***

The book contains selections from 44 authors plus an introduction by Bacevich himself. There is great diversity here, although the editor laments the preponderance of white men among the contributors: only two women and three African Americans have made the cut. Libertarians aplenty have been counted as conservatives for purposes of this collection, including Frank Chodorov (who once threatened to “punch in the nose” anyone who called him a conservative), the Chicago School economist Milton Friedman, and the anarcho-capitalist Murray Rothbard. Among the socialists, progressives, and center-Left thinkers featured herein, Christopher Lasch and Wendell Berry offer critiques of liberalism and capitalism which are indeed touchstones for certain kinds of conservatism today. The Marxist historian Eugene Genovese likewise finds many admirers on the Right for his work on the Southern intellectual tradition. Randolph Bourne, Charles Beard, Reinhold Niebuhr, and William Pfaff, on the other hand, seem to be here chiefly to reinforce the editor’s own preference for a less interventionist foreign policy—the provocative selection from Beard even argues against U.S. participation in World War II.

Yet the great names from the pantheon of 20th-century conservatism are mostly accounted for, with certain conspicuous exceptions. Russell Kirk, William F. Buckley, Jr., and Frank S. Meyer provide the book’s first three selections; they attempt to define conservatism with respect to its 19th-century history and the legacy of Edmund Burke (Kirk), the coalition embodied by National Review (Buckley), and the theme of freedom in the Western moral and political tradition (Meyer). The 21 items in the book’s second and longest section—“The Fundamentals: Tradition, Religion, Morality, and the Individual”—range from Henry Adams’s The Education of Henry Adams (1900) to Antonin Scalia ’s Obergefell v. Hodges dissent (2015), with contributors ranging from Herbert Hoover and Zora Neale Hurston to Harry V. Jaffa and Andrew Sullivan in between.

The section on “Liberty and Power: The State and the Free Market ” has fewer authors (eight) and greater focus. Likewise the penultimate section, “The Ties that Bind: The Local and Familiar,” contains just four items: one each from John Crowe Ransom, Robert Nisbet, Eugene Genovese, and Wendell Berry. The final part of the book, “The Exceptional Nation: America and the World,” is also of modest length, featuring eight authors, beginning with Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge and ending with Ronald Reagan and William Pfaff.

***

Most of these figures clearly enough have something to do with American conservatism, either as self-described conservatives or—in the case of Allan Bloom, for example—as thinkers who eschewed the label but whose work has been of obvious significance to the Right. What’s less clear is whether they relate to a common conservatism in anything more than a nominal sense: the anthology is, after all, subtitled Reclaiming an Intellectual Tradition. In his introduction, Bacevich proposes that this tradition “emerged in reaction to modernity itself,” where

[m]odernity meant machines, speed, and radical change—taboos lifted, bonds loosened…. States accrued power. Bureaucracies thickened. Banks, corporations, rail systems, and industrial enterprises grew to mammoth proportions. War became more destructive.

All the selections in these pages do touch upon one or more of these themes directly or by implication. Most also exhibit a distinct wariness about power in the hands of liberals—whether that power finds expression in overweening government, a debased cultural consensus, or the reduction of community life to the terms of economics.

Beyond that, though, the real unifying principle of American Conservatism is Bacevich himself. He comes from a midwestern Catholic background—born in Normal, Illinois, in 1947, the year the Cold War is usually said to have begun. He is a veteran of Vietnam and the first Gulf War who reached the rank of colonel; he’s seen combat and suffered family loss from war. He earned a Ph.D. from Princeton and taught at West Point, Johns Hopkins, and Boston University, where he’s now emeritus professor of international relations and history. He is also the president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft.

***

Bacevich’s personal conservatism has always been of a rather market-skeptical variety, which combines, with his critical view of American foreign policy, into an outlook that has much in common with the anti-war Left. Neoconservatives are a particular object of his ire. “[T]hey were never genuinely conservative,” he writes to explain why he has excluded them from his pages. “Neoconservatism is a heresy akin to antinomianism, its adherents declaring themselves unbound by the constraints to which others are obliged to attend.” Despite the ban, Irving Kristol, the godfather of neoconservatism—and practically the only person of consequence on the Right to apply the label to himself—is represented here by an exceptionally fine essay on the moral discontents of commercial society, “‘When Virtue Loses All Her Loveliness’—Some Reflections on Capitalism and ‘the Free Society’.”

Kristol’s wife, the historian Gertrude Himmelfarb, would have merited inclusion in this volume as well. That would have helped alleviate the regret Bacevich expresses in his introduction over the dearth of women and minorities in his pages. He has omitted some other obvious candidates, too: Clarence Thomas and Thomas Sowell, for example, and Jeane Kirkpatrick, who would have been a better choice than Pfaff to conclude the foreign policy section (and the book). If “Dictatorships and Double Standards” seems over-anthologized already, Bacevich might have chosen Kirkpatrick’s 1990 National Interest essay, “A Normal Country in a Normal Time,” which happens to dovetail almost perfectly with his own foreign policy views.

There are other right-leaning critics of American statecraft who could have reinforced Bacevich’s preferences and spared him from having to enlist so many left-wing authors. John Lukacs and Walter McDougall would have been apt choices, and while Angelo Codevilla might favor the use of force in situations where Bacevich would not, his right-wing realism would also have strengthened the foreign policy section. An excerpt from James Burnham’s The Struggle for the World (1947) does mediate between the extremes of imperialism and non-interventionism represented by the selections from Theodore Roosevelt and Charles Beard. But Bacevich’s brief introduction to the Burnham material is disparaging, and a reader who knew nothing else about Burnham would wrongly group him with the likes of T.R. on the basis of the editor’s claim that he was “a forerunner of neoconservatism.” One suspects that Bacevich would similarly dismiss as near-neocons other key thinkers of the Right who have been omitted from these pages—political realists (if not all foreign policy realists) such as Samuel Huntington, Harvey Mansfield, James Q. Wilson, Charles Murray, and Heather Mac Donald. On the other hand, Patrick Buchanan, the archetypal paleoconservative, has been kept out on the grounds that he is “not an original thinker.” Had he and another indispensable chronicler of Western self-destruction, Christopher Caldwell, been included, they would have gone far toward balancing the scales between the literary and rather romantic conservatism that is overrepresented in American Conservatism and the more hard-edged, power-conscious strain of right-wing thought. As it is, there is too much Rousseau in this volume and not enough Machiavelli.

***

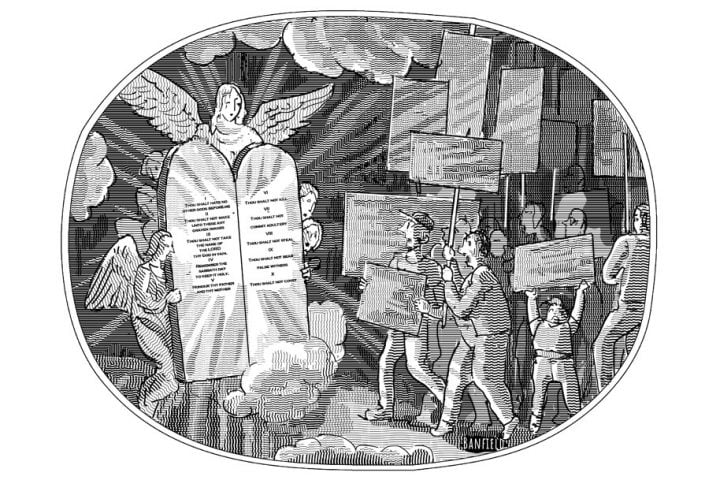

Yet nearly everything that Bacevich has chosen to include is worthy of its place. And he often succeeds in creating a cumulative effect. One of the strongest sequences consists of consecutive selections from Frank Chodorov, John Courtney Murray, Willmoore Kendall, and Harry Jaffa, four men with quite distinct points of view: Chodorov was a radical individualist, Father Murray was a Jesuit, and Kendall and Jaffa famously locked horns about the role of equality in the American regime. Yet all shared an understanding that God-given natural rights are the root of our liberties and order. How to preserve such rights in the face of the Communist challenge was a question that brought Kendall and Jaffa to propose that freedom cannot mean the freedom to end freedom—and thus in principle legal measures could be taken to suppress Communists in the United States, even if they did not pose a “clear and present danger.” Chodorov, by contrast, saw more to fear in failing to promote the philosophy of freedom than in permitting the circulation of totalitarian ideas. He dreaded the power of the state more than any subversive activity: his answer to the McCarthy-era problem of Communists holding government jobs was to “abolish the jobs.”

The selections right after that from Joan Didion (on feminism), Allan Bloom (on identity politics and sentimental nihilism), and Andrew Sullivan (on same-sex marriage) also compound powerfully. Bacevich introduces Sullivan as “arguably the most influential conservative public intellectual of his generation” for his “capacity to transform a controversial point of view into the conventional wisdom” on gay marriage. But Sullivan’s success in this was revolutionary, not conservative, and like many a Jacobin or Old Bolshevik, Sullivan now finds himself overwhelmed by the forces he unleashed.

His conservatism was, and is, of a kind dependent entirely on convention, and his argument to redefine marriage in an unconventional way was supposed to extend bourgeois benefits to homosexuals without damaging the timeless institution. Yet what has actually happened is that natural sex itself has been recast as just one more convention. If within a marriage two women are the same as two men, and the same as one man and one woman, then elementary algebra tells you a man and a woman are the same, interchangeable, and in the end, identical. If that’s true of men and women, it must be true of boys and girls, too—unless our species is the only one that is sexually distinct before the age of reproduction and sexless at maturity. Sullivan justly resists these implications. That places him on “the wrong side of history” and under constant threat of “cancellation” for being insufficiently revolutionary about the conventionality of sex.

***

Every convention oppresses somebody because every convention limits our social roles. Why not scrap them all, then, so all can be free? Or if we cannot live without such things, why not do as Rousseau advised and take conscious political control of our customs and morals, conforming them to the enlightened justice of the general will? This is what is happening with respect to sex, as customs which from time immemorial amplified natural differences are politically replaced by new customs (and laws) which do their best to erase such differences. The result, however, is to create an identity crisis as nature and custom are set at war—and we see the outcome in our confused youth. Allan Bloom saw it already in 1987, and Joan Didion reported on it as early as 1972.

For many of the contributors to American Conservatism, the remedy for modern life’s drift away from nature and its limits is to be found in a return to local community, which is also perceived as the practical check on the growth of centralized power. There is a strongly Anti-Federalist and Southern Agrarian character to this collection, most poignantly expressed by Patrick Deneen, John Crowe Ransom, Eugene Genovese, and Wendell Berry. The classical polis and its virtues loom large for Deneen as a contrast to the selfishness he sees at the heart of the liberal order. But if Sullivan goes awry by disregarding nature, Deneen is inattentive to why Aristotelian or Thomistic ideas of nature no longer seem plausible or binding in light of human experience. And if liberalism is “unsustainable,” as the title of Deneen’s essay indicates, or has already “failed,” as the title of his 2018 book states, then what are we to say about the extinction of the ancient polis and medieval Christendom?

***

This was a question with which America’s Founding Fathers grappled in only slightly less philosophical form. Yet the overall impression one receives from Bacevich’s American Conservatism is that the founders failed—that the only America worth conserving is one that doesn’t exist and never really did: an agrarian, “isolationist,” morally uncomplicated, communitarian land uncorrupted by wars, cities, industry, commerce, and political parties. The common name for the progressive, conservative, libertarian, and anti-interventionist variations on this dream is “Jeffersonian.”

What Andrew Bacevich’s book lacks most are not women, people of color, neoconservatives, or conservatives who actually agree with Bacevich’s principles. Rather, American Conservatism’s most serious deficiency is its lack of conservatives who accept modern complexity and do not counsel retreat. Conservatism cannot be confined to front porches and poetry, as lovely as those things are. It must be of the world to defeat the wolves who are within as well as outside every community’s walls.