Book Reviewed

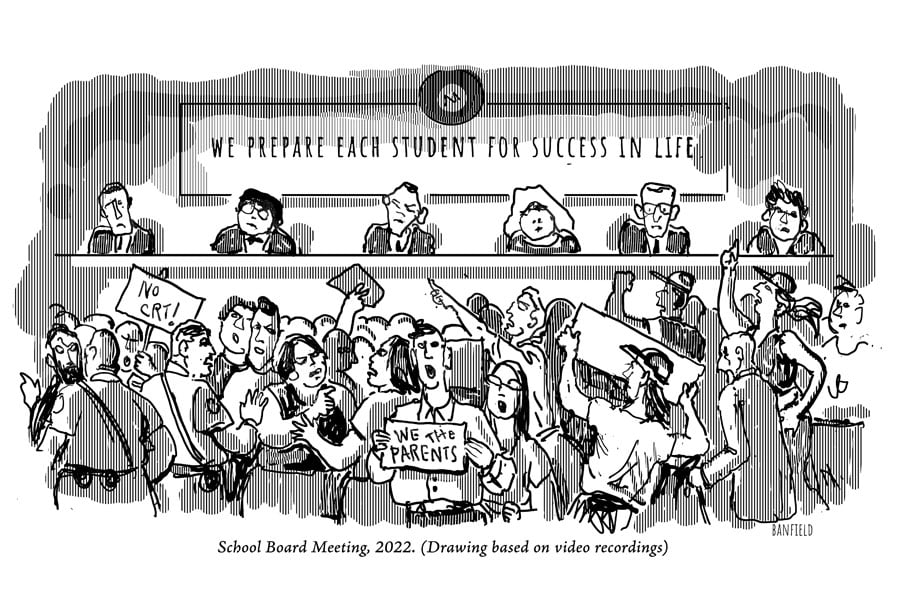

Scenes from the Loudoun county, Virginia, school board meetings riveted Americans during 2021. A girl had been raped in a school bathroom by a boy dressed as a girl. For fear of running afoul of transgender ideologues, the district covered up the crime. Soon after her father was arrested for complaining bitterly at a school board meeting, the National Association of School Boards asked the U.S. Department of Justice to treat complaining parents as domestic terror threats. An early draft of the Association’s letter called on the federal government to deploy the National Guard and military police to restrain parents at school board meetings.

Luke Rosiak’s Race to the Bottom shows that such episodes are produced by an educational system that has abandoned excellence for ideology. The proximate causes of the equity agenda include zealots in the ranks of teachers, principals, and board members. But, Rosiak shows, the ultimate cause is a system funded from top to bottom by social justice crusaders determined to transform the public schools in order to transform the country.

An investigative reporter for the Daily Wire who broke stories putting a national spotlight on Loudoun County public schools, Rosiak reveals “the secret forces destroying American public education,” as his subtitle promises. The book also shows how the Left “marches through”—captures and controls—powerful governing institutions. Once you see this process in detail here, you will see it everywhere.

* * *

As Rosiak shows, local school districts adopt the Left’s political agenda from environmentalism to forced busing (now back with a vengeance). Starting with the most local but rising to a shadowy level of national players exempt from effective political control, Rosiak reveals the story in layers. Each comes with a case study and explanation, followed by another layer. By the final chapter a complete picture has emerged.

For every pedagogical failure, readers learn, our education industry devises a public relations solution. When too many students fail to attend enough school to graduate, schools create “credit recovery” systems, as happened in Brooklyn: bogus, pass-through classes allowed students to meet graduation targets. When 94% of Bronx students passed their math classes in a year but only 2% showed proficiency on standardized math exams, the standardized tests were denounced as measures that stifled students’ creativity and forced instructors to “teach to the test.” When black males were disproportionately likely to be suspended from schools, districts responded by “Rethinking Discipline” in ways that kept students out of the “school-to-prison pipeline.” The number of suspensions in Los Angeles fell from a combined 75,000 days in 2007-08 to 5,000 seven years later because troublemakers were allowed to continue making trouble. When millions of students need remedial courses at college, the institutions recalibrate their standards so that these remedial courses can be called something else.

The fundamental problem, Rosiak shows, is that local school boards are vulnerable to outside manipulation and control. In theory, these elected bodies are meant to bring the local community’s interests and sensibilities to bear on the complex job of administrating schools. In practice, outside forces can co-opt school boards, which often lack sources of information independent of school administrations. As a last resort, school board elections can be bought and sold, most often by well-funded teachers unions.

* * *

When parents seek to penetrate a district’s public relations cloud, the teachers, staff, and school boards close ranks to prevent transparency, much less accountability. Having long ago recognized that school boards threaten their sinecures, teachers and administrators captured boards so that no independent force can criticize professional educators. School board members are often teachers or the family members of teachers. In Loudoun County, Rosiak shows, six of the nine school board members were either teachers or a teacher’s spouse. No dispute between management and labor can arise when teachers represent both. Teacher union officials control many Parent-Teacher Associations as well. When genuinely independent candidates do run for school boards, unions, school officials, and outside donors make sure that establishment forces outspend and outwork the interlopers. School board elections, usually drawing ballots from a small fraction of registered voters, are easily rigged by teachers with their deep, abiding interest in the outcome.

The second layer in the system arises from national movements like Common Core and national laws such as the Obama-era Every Student Succeeds Act. These create national markets for activist trainers and curriculum suppliers as localities struggle to meet the new standards. Curriculum and teacher trainers—almost all of them are controlled by foundations and other sources of funding on the Left—arise to help districts meet these new standards.

For example, the George Floyd riots in 2020 merely expanded the calls for services like “Courageous Conversation” from the consulting firm Pacific Educational Group (PEG), which provides training for teachers, administrators, and school boards. Consultants routinely charge districts six-figure fees for such services. Edina School District in Minnesota, once one of the best in the country, contracted with Glenn Singleton, PEG’s owner, to train teachers in “educational equity” and “decolonizing” the curriculum. An English teacher inspired by Singleton stopped teaching literature with the Socratic method and started teaching “active social justice work.” When a school board member complained about reduced academic performance, other board members, in the district’s employ, disciplined her. Meanwhile, the English teacher was named Minnesota Teacher of the Year. Rosiak shows how such consultancies spawn ever more work for consultants, even though (or perhaps because) academic results decline.

* * *

Complementing such consultants are curriculum suppliers like Learning for Justice, funded through the Southern Poverty Law Center, or EdJustice, the National Education Association’s activist arm, each of which provides lesson plans consistent with Common Core and Black Lives Matter. Also available are Action Civics or Project-Based Civics or the New Civics, which are about teaching activism to students, more and more of whom know less and less about the basic facts of American history or government. This new government money is, in effect, used to create student activists who lobby government to fund student activism.

The least accountable and most important layer in the public education space is private foundations. “These rogue foundations are perhaps the most radical, powerful, and least understood force in American politics,” writes Rosiak. Ones like the Gates Foundation helped design Common Core standards that called for new curriculum and training. Big foundations fund studies that unions, school boards, and activists use to criticize testing, demand more equity programs, or dilute teaching standards. Wherever there’s an educational cover-up, trendy cause, or new curriculum, big foundations are near the scene of the crime.

President Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative to get local school districts to loosen disciplinary standards was funded with $15 million from the Kellogg Foundation. When studies showed that discipline-lax restorative justice programs led to more violence and less student success, the George Soros Foundation dropped $1.2 million to get schools to implement the programs anyway. The FairTest group, known for criticizing standardized testing, is an arm of the National Education Association, funded through grants by the Ford, MacArthur, and Soros foundations. FairTest’s former executive also heads up the Advancement Project, a black advocacy group funded by Ford and Kellogg. The 1619 Project was seeded by millions from MacArthur. It is impossible to measure just how much big foundations spent on equity and school reform generally. Among Gates, Ford, Kellogg, and MacArthur, the number surely exceeds $3 billion over the past decade.

Such foundations also provide personnel to staff new equity bureaucracies within school districts. Within schools they fund youth groups like the Gay-Straight Alliance for activists, who, in turn, lobby sympathetic school boards to fund more youth-centered groups. No one speaks on behalf of real education. As test scores go down, the well-funded public relations machine controls the education megaphone. Anyone who criticizes public education, it is said, hates teachers or wants to undermine public education. Foundations support the canard that more education spending and hiring will solve every problem.

* * *

To augment their enormous power, the big foundations collaborated with others to establish New Venture Fund, a non-profit that promoted activism with at least $2.7 billion between 2015 and 2019—and more since. New Venture Fund seeded educational media in many states, where websites and “reporters” carry water for the education establishment, while hiding what is really going on. The websites have homespun names—Sounds like Tennessee or Colorado Chronicle—but they are covers for foundations promoting the equity agenda in schools. Teacher of the Year awards are funded. Board members for national organizations of school boards or overseeing certifications come from the foundation funding world. “Groomer clubs,” as their critics deride them, pop up “spontaneously” in high schools and middle schools, headed by sympathetic faculty receiving stipends through local groups.

Rosiak concludes with case studies of New York’s famous Stuyvesant High School and the imposition of the “One Fairfax” busing program in Virginia’s Fairfax School District. Stuyvesant, one of the first and most successful magnet schools, was a testament to an achieving, meritocratic America. As such it was a standing insult to the educational public relations show and the equity industry. First, political officials in New York attacked the standardized tests by paying $400,000 to a Kellogg Foundation-backed group called the Center for Racial Justice in Education to persuade parents that the meritocratic schools were racist. Parents complained, but the politicians ordered police to stop parents from participating in open forums.

When the city reached an impasse in 2019, Mayor Bill de Blasio appointed Maya Wiley, a former senior advisor in the Soros Foundation, to establish a School Diversity Advisory Group to provide further academic cover for stopping admissions to select students based on test scores or grades. Then federal programs for Action Civics became important, as AmeriCorps hired adults to recruit students to advocate the elimination of admissions standards. Students wrote plaintive letters and provided public testimony about how they loved “educational equity” and hoped to have government dismantle oppressive institutions. Government money was used to lobby government under the government’s direction. Activists within de Blasio’s administration, planted there under earlier efforts to expand equity, used their small empires and large budgets to insist that implicit bias and inequitable funding accounted for every aspect of poor academic performance. Admissions standards have been watered down as a result—all students who score above a certain threshold are placed in a lottery and have an equal chance of admission. Efforts to return to a strictly merit-based enrollment have failed, but it could be worse.

The Fairfax, Virginia, example is a small-scale model of New York’s experience. A local school board allowed itself to be lobbied by researchers, activists, teachers unions, students, and others to impose a district-wide busing policy, even though there were no discernible racial inequities in the school district. Rather than use the term “busing,” the educrats’ jargon stressed the importance of “intra-district zoning policies that maintain socioeconomic and racial equity as its [sic] guiding principle.”

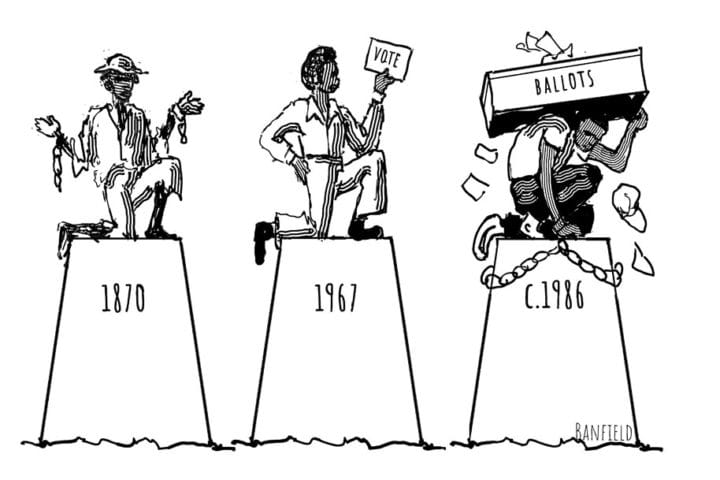

It’s comforting to think that government closest to the people is the most accountable to the people. Determined minorities, animated by powerful ideologies and big money, can, however, win despite the wishes of local communities. This happens repeatedly, Rosiak shows. Citizens support merit-based pay, only to find that, according to teachers and consultants, 99% of teachers are above average. Teachers unions are hardly popular, but they rule schools and systems. Less than 40% of the country trusts institutions of public education, but little radical restructuring happens. No one in Fairfax wanted busing, but busing they got. New York manufactured consent for transforming popular magnet schools.

* * *

Rosiak’s book demonstrates that local governments aren’t really all that local. With national laws as the opportunity, private foundations and their allied consultants, researchers, and curriculum developers leverage bigness and necessity to have their way. Foundations are usually pushing on an open door, since the education establishment wants to go where foundations are taking them. Foundations are two steps ahead, as Rosiak writes, but all are tending in the same direction.

America’s public education system, health authorities, intelligence agencies, higher education, and other institutions suffer from trust deficits. “I am no longer sure America’s public school system can be saved,” concludes Rosiak in his epilogue. Given their record of “manipulating data, lying, and keeping the public at bay,” he writes, trusting public school officials’ promises or data requires that hope prevail over experience. Rosiak believes sending his kids to the local Fairfax County public schools “would amount to child abuse.” Since more than 80% of American students attend public schools, this portends a dark future for the country.

Only determined, persistent efforts could rescue this sinking ship. That means, first, destroying the grip of the educational establishment by using methods like school choice and alternative accreditation.

Still, no nation can ever depoliticize education, so “choice” programs are never enough. Education is always political. That means, second, that parents and school board reformers need to insist that schools teach sensible, intelligent patriotism and the analytical skills necessary for life in a modern commercial republic. State governments willing to require such basics are indispensable, too. Efforts to work backward through the institutions, eliminating malign forces, should be on the minds of every conservative.