With Moscow and Washington staring each other down over Ukraine, it is imperative to understand the man who controls Russia’s nuclear arsenal. This is the most dangerous proxy war in decades, yet there is little agreement or knowledge in the West about our adversary. Many American and European press reports portray Vladimir Putin as a Hitler-ian madman bent on world domination, and now a war criminal to boot, against whom we all must rally to save Western civilization. To certain admirers on the American Right, by contrast, Putin is a disciplined statesman who stands up to Western meddling in defense of Russia’s core interests, his unapologetic nationalism buttressed by old-fashioned masculine courage. The contrast between these two portraits could not be more jarring.

But however consequential a statesman he has been, the real Putin is much less colorful than these caricatures. Though he is a competent politician capable of delivering well-received speeches, Russia’s president has never relished public adulation: he lacks the charisma of the demagogue. Despite various successes and a few notable failures in the foreign policy realm—and at the time of this writing it is not yet clear where the Ukraine war will fall on this spectrum—Putin is also a less visionary statesman than his admirers believe. Nor is Putin an especially original thinker. Certainly he is more cunning, more genuinely curious about the world and how it really works, and consequently more effective, than most Western statesmen today. But that is an embarrassingly low bar in the age of mediocrities like Joe Biden, Justin Trudeau, Emmanuel Macron, and Olaf Scholz. The closer one looks at Putin and his political career, the less remarkable he appears. Putin is at his core a quintessential Russian state servant, a career bureaucrat who ascended to national leadership because of his more mundane qualities, not because of any that made him stand out.

Putin grew up in material circumstances that Americans might consider “working-class,” and his path into the Russian elite was not easy. But his family was well connected. Putin’s grandfather Spiridon, a talented chef who once cooked for Rasputin, survived the revolution to cook for Lenin, Lenin’s widow, and Stalin as well. Because Spiridon Putin could not have been trusted with such sensitive work absent the highest-level security clearance, it is generally assumed that he worked for the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs—the secret service, or NKVD. Putin’s father, Vladimir, also served in the secret police, although in his case it was in an elite combat unit fighting the Germans on the Leningrad front in World War II. The family suffered terribly like others during the Leningrad siege years—Vladimir’s older brother Viktor died of diphtheria at age two—but both parents survived.

After the war, the Putin family lived in a typical communal apartment in Leningrad, and his parents worked hard in factory jobs. Young Vladimir, born in 1952, would be the first in the family to go to college. Still, by Soviet standards the Putins were decently well off, and they had social standing—no one in the family seems to have fallen afoul of Soviet authorities in the Great Terror or war years, and Putin’s father was a wounded war hero. Although there was no formal “Table of Ranks” in the USSR, the University of Virginia’s Allen C. Lynch argues in Vladimir Putin and Russian Statecraft (2011) that the Putins were something like petty Soviet nobility, a proud family known for loyalty to the “throne”—which is to say the Communist Party.

The only unusual part of Putin’s early life is that he was rejected by the “Pioneers,” the Soviets’ more ideological version of the Boy Scouts. It was not for political reasons, though—Vladimir was a lazy student and something of a schoolyard bully, prone to fighting. It was only after Putin discovered martial arts, at the age of 13, that he matured and began to take his schooling seriously—he became particularly proficient in German. A few years later, Putin visited a local KGB branch and asked to be recruited. Though he was rebuffed and warned not to try anything like that again, a file was opened and Putin was recruited into the agency shortly before finishing his college degree in law, with a focus on economics and international relations.

From Jobless to President

Putin’s reverence for the Russian state, in whatever form it has assumed since the days of Ancient Rus, was and remains his defining feature. It is patriotism of a sort, but not the flag-waving or self-sacrificing kind most of us are familiar with. Joining the KGB is not really the same thing as volunteering for the national guard, the army, or, say, the local fire department. It is a calling of a much colder variety, entailing a certain distance from the people one is not so much serving as looking down upon from above. One of Putin’s first tasks as a young KGB officer was harassing dissidents and dispersing protests—a job at which he excelled. Unlike a soldier, a KGB operative rarely risked his life, especially in a “friendly” Soviet-occupied country such as East Germany, where Putin was posted from 1985 to 1990, putting his German skills to good use in Dresden.

Still, if he did not exactly sacrifice himself for his country, Putin made himself useful to his bosses, displaying an impressive work ethic, following orders, and seeing things through. After returning to Russia in 1990, Putin, unlike many of his fellow KGB officers, did not cash in his connections to profit from Russia’s collapse. He even declined a prestigious KGB job in foreign intelligence in Moscow, because he wanted to stay close to his family in Leningrad. Instead he took a job in the dean’s office of Leningrad State University, spying on foreign students.

The main quality that appealed to Putin’s superiors throughout his career was his loyalty. After the failed coup of August 1991, Putin did receive permission to leave the KGB and work for Anatoly Sobchak, mayor of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). But he did even this out of a sense of obligation: Sobchak had been one of his favorite undergraduate teachers, instructing the future president in economic law. Putin served his old professor faithfully: there is a famous story that he reported former KGB comrades for trying to get him to forge the mayor’s signature. He was so devoted to his boss that, when the mayor was voted out of office in 1996, Putin helped whisk Sobchak out of the country to avoid prosecution on corruption charges.

Among Putin’s briefs as deputy mayor was negotiating food imports, a sensitive issue for a Leningrader whose older brother had died in the siege of 1941-44. While working in the mayor’s office, Putin wrote an economics dissertation for a candidate degree (loosely the equivalent of a Ph.D.) on the “Strategic Planning of the Reproduction of the Mineral Resource Base of a Region under Conditions of the Formation of Market Relations.” The region in question was his native St. Petersburg. The prose of the thesis is uninspired, and it seems doubtful that he actually wrote the more technical passages himself, but he clearly took an interest in the subject. The key theme, whether developed by Putin or a ghostwriter, was the need to harness market economics and foreign trade, while keeping the government firmly in the driver’s seat and ensuring that favorable deals were negotiated with Russia’s vast mineral wealth as collateral. “Mineral and raw materials,” the dissertation concludes, “represent the most important potential for the economic development of the country,” and they should therefore “be regulated by the state…acting in the interests of society as a whole.”

There is a paranoid school of thought which sees in the ascendancy of Putin and his old siloviki cronies from Leningrad a grand design, as the KGB plotted to take back control of the Russian state after the chaotic free-market liberalism of the Boris Yeltsin years. Putin’s career arc is certainly improbable enough to intensify such suspicions. After Sobchak’s fall in 1996, this ex-KGB officer was appointed first to run Yeltsin’s “Property Management Department,” with oversight over the Kremlin’s vast real estate empire, then to head the GKU or “Main Control Directorate,” overseeing (and sometimes quashing) corruption investigations. Then, in July 1998, Putin became the head of the KGB’s successor spy agency, the FSB, from which post he was promoted by Yeltsin in 1999 to secretary of the Security Council, prime minister, and then acting president. As political scientist Karen Dawisha dryly observes in Putin’s Kleptocracy (2014), Putin went from “jobless to President in three and a half years.”

The problem with this theory is that no one predicted the rise to power of Putin and his old secret police or siloviki cronies in August 1999 before it happened, least of all Putin himself. His two immediate predecessors as prime minister, Yevgeny Primakov and Sergei Stepashin, had much higher profiles. Primakov, a former foreign minister who had also worked for years in the KGB’s foreign intelligence branch—at a far higher level than Putin—was appointed to appease the Duma after Russia’s embarrassing default in August 1998. Primakov was so independent of Yeltsin that, upon being sacked in May 1999, he teamed up with the popular mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov, to form an opposition party called “Fatherland–All Russia” (OVR). OVR soon led national polls, and in the feverish political atmosphere of summer 1999—with Russia reeling from a financial crash and humiliated by the U.S.-NATO “Kosovo War” conducted against her Serbian client from March to June—there was talk of impeaching or prosecuting Yeltsin if OVR won the Duma elections in December. It was assumed that Stepashin, an old intelligence hand who had been one of the “hawks” in Yeltsin’s inner circle when the First Chechen War was launched, was the strongman who would see off OVR and protect the Yeltsin “family.” Putin, though a well-connected Kremlin insider, was unknown to the general public and featured on almost no one’s political bingo card.

Avenging Russia’s Wounded Pride

Thus Putin was little more at first than a useful cipher, a political blank slate onto which an image could be grafted. In the first poll of possible presidential successors to Yeltsin taken after his appointment, Putin received just 2% of the vote. As Putin himself told Yeltsin, “I don’t like election campaigns. I really don’t. I don’t know how to run them, and I don’t like them.” Neither charming nor magnetic, Putin was nonetheless seasoned, unafraid, and willing to do the political dirty work. There is still controversy over the outbreak of the Second Chechen War in the wake of a series of apartment terror-bombings in Russian cities in September 1999. Some allege collusion between Yeltsin insiders and the rebel leader Shamil Basayev. One of the bombs that did not go off, in Ryazan, even turned out to have been planted by the FSB. Scrambling quickly, Putin’s successor as FSB director, his old KGB comrade Nikolai Patrushev, announced that this was a fake bomb, put in the basement of a large Ryazan residential complex as a training exercise. Patrushev congratulated residents and local police for their “vigilance.”

Whether or not Putin had anything to do with the suspicious Ryazan “exercise,” he reaped the political benefits as Russia sought vengeance for the other apartment bombings, famously vowing on September 23, 1999 to “waste” Chechen terrorists “in the outhouse.” By October, Putin had caught up to Primakov in the polls (at 27-28%); by November he surpassed him at 40%, having meanwhile assembled a pro-Kremlin political party called “Unity.” Unity handily beat OVR in the December Duma elections, finishing a close second to the Communists. On the Y2K New Year’s Eve 1999–2000, in the traditional presidential address given to herald the New Year, Yeltsin named Putin his designated successor as acting president. Putin was on his way, and he has never looked back.

To the extent he had a mandate, it was to restore the dignity of the state after the iniquities of the 1990s. Yeltsin’s reelection campaign in 1996 had been financed by corrupt oligarchs who benefitted from a grotesque series of “Loans for Shares” auctions, acquiring control of oil and gas companies for a song even as Russia de-industrialized, the country’s assets were looted, and billions of dollars disappeared into foreign banks. The corruption was so over the top that many Yeltsin advisors were photographed with suitcases full of cash, and Yeltsin frequently embarrassed himself with displays of public drunkenness.

Putin certainly restored sobriety to the Kremlin, along with state control. Oligarchs who refused to play ball, such as Vladimir Gusinsky, Boris Berezovsky, and Mikhail Khodorkovsky, were shown the door, exiled in the first two cases and jailed in the third. Capital flight declined from $15 billion annually in the late Yeltsin years to $3 billion by 2003; Russia’s foreign debts dating back to the late Soviet period were paid off in full and ahead of schedule; and Russia’s gold reserves began a steady climb which continues to this day. After a period of uncharacteristic weakness, the Russian state was back, the private sector brought to heel.

Likewise, Putin restored Russian military prestige by bludgeoning Chechnya into submission after the debacle in the First Chechen War, when in June 1996 the Chechen rebels had reconquered their capital largely by bribing their way into Grozny past army checkpoints, as Russian officers sold out their men. However brutal the methods, however horrendous the casualties, there is no denying that Russia won the Second Chechen War, after losing the first.

To be sure, the price of these victories was high. We really do not know how many soldiers and civilians died on both sides in the Second Chechen War, but estimates run from the high five figures to the low hundreds of thousands. Grozny, already hard hit in the first war, was pulverized. In the Beslan school hostage episode of August-September 2004, which took place in North Ossetia in Russia’s North Caucasus region, more than 300 children perished along with 31 Chechen terrorists. The Beslan catastrophe also put paid to the last vestiges of local democratic autonomy in the Russian Federation: Putin used the crisis as a pretext to end direct election of regional officials, thereafter appointing governors directly (subject to ratification by regional parliaments). Putin thus completed the top-down revolution in Russian constitutionalism he obliquely referred to as the vertical’naya vlast’ or “vertical line of power.”

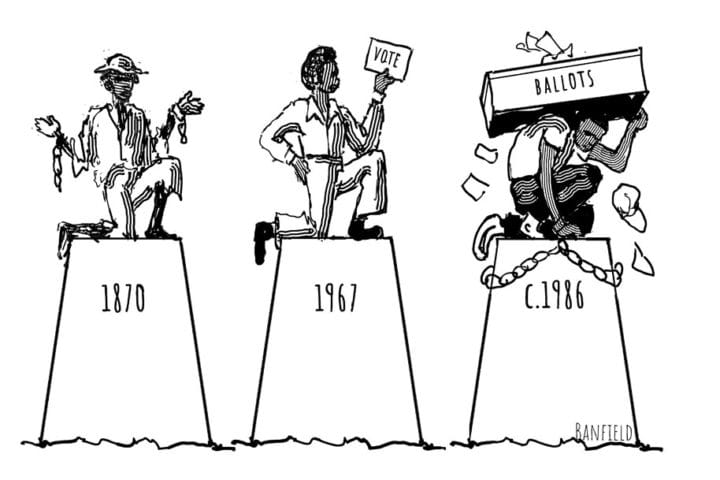

Putin never really cottoned to democratic politics—perhaps he intuited, as Hitler did of the Germans in his day, that most Russians didn’t like it much, either. There was, for a time, a pro-Putin youth group called Nashi or “Ours,” at one point boasting 120,000 members. This was compared by Western critics to the Hitler-Jugend and the old Soviet Komsomol, with their disturbing air of indoctrination and great-man worship. But the resemblance is only superficial. Aside from sharing pictures of a shirtless Putin hunting, fishing, and wielding rifles, Putin’s handlers never made much of an effort to develop a personality cult, almost certainly because Putin himself had no interest in doing so. Nashi no longer exists.

Mid-Level Authoritarianism

There has also been much tut-tutting in the West about the supposed anti-Semitism fueling Putin’s crackdown on “liberal” Russian oligarchs who happened to be Jewish. But Mikhail Fridman, one of the original “Loans for Shares” oligarchs, was no less Jewish than Berezovsky, Gusinsky, and Khodorkovsky, and his holdings were never touched. Putin is actually philo-Semitic, having grown up with many Jewish friends. His German teacher in high school was Jewish and, as Lynch recounts, Putin revered her so much that he sought her out on a state visit to Israel and purchased an apartment in Tel Aviv for her. It is not ethnicity or religious identity that matters to Putin, but loyalty to the Russian state. Western critics may imagine Putin as a racial chauvinist, but Russia remains a multi-ethnic empire, as it was under both the tsars and the Soviets. At a public pro-war rally on March 18, 2022, Putin proudly declared that “we, the multinational people of the Russian Federation, are united by a common destiny for our land”—the land where Russians have traditionally lived and ruled.

In the current war, it is not the Russian but the Ukrainian government which has flirted with racial supremacism, claiming in a now-deleted tweet that “Ukrainians originate from Slavic tribes. The Russian nation was formed to a large extent from mixing.” By contrast, Putin has notoriously leaned on Muslim mercenaries from Chechnya and Syria. It may be that Putin’s generals are outsourcing the more gruesome tasks in this increasingly ugly war because they lack faith that Russian soldiers will follow through on orders to kill fellow “Slavs.” But there is nothing inconsistent in this with historical precedent. Not unlike the late tsarist empire, or the British empire, Putin’s Russia prizes minority peoples who know how to fight—who like to fight. Putin is a traditionally Russian kind of imperialist, whose empire welcomes non-Russians, as long as they are loyal to Russia.

One can see similar echoes of the tsarist past in the area of censorship. The invasion of Ukraine in February precipitated an obvious escalation, which has seen the shuttering of the last truly independent Russian media organizations (Echo of Moscow radio, Dozhd or “Rain TV,” and Novaya Gazeta or New Times). But constriction of press freedom dates to the earliest Putin years. In the 1990s, biting critiques of the First Chechen War were aired on primetime television, including on a popular puppet show (Kukly) which skewered Yeltsin as a feeble drunk. One unforgettable episode, aired during the Kosovo War, depicted Yeltsin as Bill Clinton’s poodle, and Clinton as a warmonger unable to control his machine gun’s, er, ejaculations. (A popular cocktail in Moscow at the time, the “Lewinsky Dress,” featured Blue Curaçao and cream.) After the rigid information control of the Soviet period, and the obtrusive though inconsistent tsarist censorship, this was all great fun—but wholly out of sync with Russian tradition.

It was not fated to last. One of the first signs of the Putin effect was tightened limits on the press in the Second Chechen War, manifested not least in the end of Kukly: Putin did not appreciate being caricatured as a big baby. Much as the Pentagon learned its lesson from Vietnam and applied stricter press controls in the Gulf War of 1990-91, Russia fought its second round in Chechnya under a media blackout. This new crackdown made international headlines in January 2000, when the Russian Army kidnapped a critical Russian reporter, Andrei Babitsky, in perverse homage to Chechen rebels who often kidnapped Westerners for ransom money.

Putin’s authoritarianism falls in a middle ground between Russia’s tsarist and Soviet inheritance, more heavy-handed than the former but less totalitarian than the latter. Soviet-style purges of the disloyal have returned, along with mysterious deaths of journalists such as Anna Politkovskaya, the poisoning of defectors like Alexander Litvinenko and Sergei Skripal, and the shocking assassination of opposition figure Boris Nemtsov near the Kremlin in 2015. All that said, whether or not Putin was personally responsible for these attacks, the cumulative body count in two decades is less than was rung up in an hour during Stalin’s Terror.

Glory Days

Still, a certain nostalgia for Soviet times is hard to miss. As early as 2004, Putin’s campaign team unveiled posters of Stalin and Solzhenitsyn, celebrating the USSR’s most famous dissident—and the dictator who persecuted him. On a visit to Poland in 2010, Putin acknowledged Soviet responsibility for the “Katyn Forest” massacre of nearly 23,000 Polish officers and elites in 1940—only to insinuate callously that Stalin ordered the executions to retaliate for Polish atrocities against Russian prisoners of war captured in 1920. Putin has disowned Communism and Lenin, while presiding over the rehabilitation of the Stalin cult, which is, by some measures, stronger than ever in Russia. Statues of Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder of the Cheka, forerunner of the KGB, were removed in the early Yeltsin period, only for several to be re-erected in recent years.

It would be wrong, however, to view Putin as an atheist-Communist retread. Helped along by a state-financed cathedral building binge, the influence of the Orthodox Church in today’s Russia is real and growing, though tinged with elements that would not have been out of place in the USSR. Since U.S.-Russian relations went into a deep freeze after the Ukraine crisis of 2014 and the “Russiagate” hysteria of the Trump years, conservative talking points in Russia’s religious revival have merged with hoary old Communist tropes about American capitalism. In December 2018, I caught a blast of the emerging fusion while discussing a historical documentary on the Orthodox TV channel Spas. Both the documentary and most of the commentators lustily blamed Americans, in particular Wall Street bankers, for the outbreak of World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, and the murder of the now-sainted Romanov family in 1918. Dissident voices (such as mine) pointed out that this was an utterly evidence-free interpretation, ahistorically reading post-Cold War levels of U.S. power and influence back into the early 20th century. But the general sentiment in the room remained that Americans were to blame for just about everything from 1914 to today. Not a few Russians told me that, to reverse the tragic, U.S.-manipulated course of Russia’s modern history, the old monarchy should be restored—with Putin as tsar.

Is this what Putin wants? A new monarchy, beatified by the Orthodox Church, celebrating ever more grandiose military parades? Writing in the Spectator (“Vlad the Invader,” February 2022), historian Niall Ferguson reports that Putin keeps a “towering bronze statue” of Peter the Great (who reigned 1682–1725) over his desk in the Cabinet room, suggesting a model. Peter’s reign was defined by the construction of Putin’s native St. Petersburg and Russia’s historic military victory over Sweden at Poltava in Ukraine in 1709, heralding Russia’s rise as a European power. As Putin himself claimed in a speech on June 9, by winning the “Great Northern War” with Sweden, Peter did not so much conquer new foreign lands as “return [what was Russia’s],” a clear allusion to Russia’s current mission in Ukraine.

And yet Peter’s Russia never did conquer Ukraine, forfeiting a hard-won naval base on the Sea of Azov after losing a battle with the Ottomans in 1711. Peter was also a ruthless autocrat who forcibly Westernized Russian culture, or tried to, and weakened the Orthodox Church by ending the Moscow Patriarchate. Putin may admire Peter’s “vertical” statist autocracy, but his own legacy, after the Ukraine war, may be a very un-Petrine bifurcation of Russia from the West.

It is unclear whether this is by design. In an article posted at kremlin.ru in July 2021, Putin spoke ambitiously about the “Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” aiming to restore a shared identity he claims was unnaturally dissolved by Western meddling, epitomized in 2014 by the U.S.-backed Euromaidan Revolution (or “coup”) and the flow of American aid and arms ever since. As Putin said in his speech on February 24, the day of the invasion, “all the peoples living in today’s Ukraine…must be able to enjoy the right to make a free choice” about whether or not to join “their historic homeland, Russia,” as Crimea allegedly did in its 2014 referendum. More menacingly, Putin added that the aim of the invasion was “defending Russia from those who have taken Ukraine hostage and are trying to use it against our country and our people.” In this line of thinking, once Ukraine is weaned from the temptation to join NATO, she will return to her natural orientation as a vital Eastern Slavic component of “historic” Russia.

As the war has bogged down, however, Putin’s rhetoric has darkened. The fierce resistance of Ukraine’s armed forces, and of her people, vitiated Russian hopes of winning a quick victory and installing a friendly regime in Kyiv. Since February, Putin has ever more loudly emphasized “disarmament” and “de-Nazification,” all but conceding that Ukraine is not really part of Russia, but rather a hostile buffer state to be chastised and punished. Alexander Dugin, the philosopher who has been called “Putin’s brain,” wrote on the digital platform Telegram that “the military operation is directed against Atlanticism and globalism. The unipolar world is liberal Nazism…. And Ukraine, seduced by liberal-Nazism, believed it and succumbed to the provocation.”

Stumbling into Global Conflict

With the war of weapons turning more brutal and the war of words more heated, is Putin finally morphing into the “Eurasianist” Dugin has long wanted him to be? In his now-infamous “foie gras” speech on March 16, Putin denounced Russian elites unwilling to forego Western luxuries as “traitors” who must be “cleansed” (or “spit out like flies”). The harsh nationalistic rhetoric seems to be working, judging by Putin’s skyrocketing approval rating, now above 80%. As journalist Farida Rustamova reported from Moscow on March 31, 2022, “sanctions and propaganda have rallied even those who were against the invasion around Putin,” such that “Putin’s dream of a consolidation among the Russian elite has come true.” Rich Muscovites and Petersburgers may not need foie gras after all—nor Netflix, McDonald’s, or Disney, which have pulled out of Russia. As one government official gloated to Rustamova, “now they’ll have to buy rubles on the Moscow exchange just to buy gas from us. But that’s just the beginning. Now we’re going to f[–]k them all.”

There is something poignant in Russia’s failure to achieve the acceptance by the Western world which has defined national aspirations since the time of Putin’s hero Peter the Great. Perhaps Russians feel a certain Schadenfreude in finally purging their national inferiority complex. But there cannot be true celebration in rejection. Despite his cresting popularity amid the fires of conflict, in recent newsreels Russia’s president looks grim. Putin does not appear to be a happy warrior.

He often insists in his speeches that Russia wishes to be a “normal country,” disowning the old Soviet—and tsarist—messianism. The fact that Russia has become a lightning rod in the emerging split of East and West may excite philosophers like Dugin, but there is little sign that Putin shares this enthusiasm. We should not forget that Putin studied German, not Chinese, that he comes from the city Peter founded as a Window on the West, and that his entire career has been defined by close study of, and confrontation with, the United States and NATO. Despite his having launched a Ukraine invasion which now looks more and more like an existential struggle against the West, one gets the sense that Putin has resigned himself to this role less out of conviction than a traditional Russian fatalism. For the rest of us, the return of an iron curtain in eastern Europe is hardly something to celebrate.

It is tempting to search through Putin’s record for lessons in statecraft, whether positive or negative, but we must resist the urge to generalize from his country’s unique and troubled path. Putin is a Russian statesman operating in a long authoritarian tradition that affords him almost untrammeled control of domestic and foreign policy. He is not beholden, as western European and American politicians are, to democratic and civic institutions—however hollowed out these may be today. We can find solutions to our own policy dilemmas neither by emulating Putin’s approach to statecraft nor by demonizing him as a new Hitler whose villainy gives meaning to our increasingly empty national life. Our salvation must come from within.