Books Reviewed

Nearly a half century ago, in his 1968 election and 1972 reelection, Richard Nixon helped initiate the movement of blue-collar workers from the New Deal Democratic coalition to the Republican Party that accelerated under Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, and was decisive in Donald Trump’s 2016 victory.

In many ways, Nixon was Trump’s opposite. He grew up poor, not wealthy; became a lawyer, not a businessman; was socially and physically awkward, not athletic and outgoing; was intensely intellectual, not impulsive and intuitive; and was a longtime, not a fickle, Republican, convinced when choosing between the parties in his early adult years that “a continuing drift toward a planned economy was perilous.”

The most important difference between Nixon and Trump, of course, is that Nixon spent nearly all of his adult life in politics and government: four wartime years at the Office of Price Administration and in the navy, four years in the House of Representatives, two years in the Senate, eight years as vice president, and 12 years as a presidential candidate or ardent campaigner for his party’s nominees in every national election from 1960 to 1972. But there’s also the quality that Nixon biographer John A. Farrell could with equal accuracy find in Trump: “He yearned, above all, to be a great man. He had that sense of drama.”

* * *

Farrell, who has previously written about Clarence Darrow and Tip O’Neill, recounts with literary grace and surpassing empathy Nixon’s life as a striver, always feeling that he was on the periphery but wanting desperately to be at the center. His father, Farrell writes, was a “cranky blowhard” and his mother was remote and, for much of Nixon’s youth, preoccupied with caring for two of his brothers, both of whom died from gruesome diseases. His family’s hardscrabble finances, which kept him working long hours in their barebones grocery store, prevented Nixon from applying for the scholarships Harvard and Yale alumni encouraged him to seek. At Whittier College, small and local, he co-founded a new social club, the Orthogonians, because the rich kids’ society (the Franklins) wouldn’t take him. “Glee clubs and choirs prized his voice,” Farrell writes—who knew?

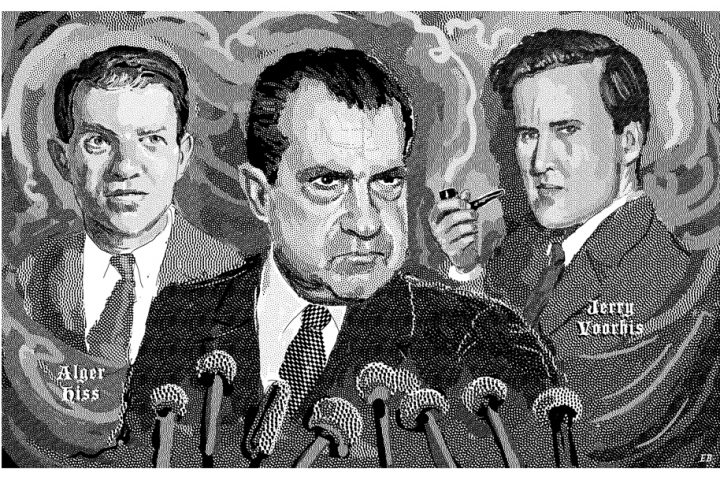

Nixon left California for law school at Duke, which offered him a full ride but whose degree back then, even though he finished first in his class, did not open doors at the best New York firms. His election to Congress in 1946 against wealthy incumbent Jerry Voorhis was resented by Washington society, which found the “handsome, pipe-smoking” Democrat properly liberal and clubbable. The same was true when he took down Alger Hiss, whom Nixon knew (and Farrell knows) to have been a Communist spy even as he was serving in the upper reaches of the State Department. “Johns Hopkins and Harvard,” Hiss sniffed when Congressman Nixon asked about his alma mater. “And I believe your college is Whittier.”

Farrell rightly observes that the Hiss case had a galvanizing effect on the budding conservative movement, bringing together “[Senate Republican leader] Bob Taft’s Old Guard, young literati like William F. Buckley, Jr., the blue-collar admirers of Senator [Joseph] McCarthy, and an inchoate crop of Sunbelt activists.” Among other things Hiss “inflamed their hostility toward the Ivy League elite.” So did the Left’s disdainful reaction to Nixon’s defeat of nose-in-the-air Helen Gahagan Douglas, who accused him of having a taste for “nice unadulterated fascism” in their 1950 Senate election. Two years later Republican presidential nominee Dwight D. Eisenhower put the 39-year-old Nixon on the ticket both for—in Nixon’s own words—his “rocking, socking campaign” style and his commitment to an active role for the United States in international affairs. This commitment was deeply rooted. Nixon had supported the Marshall Plan against the wishes of his southern California congressional district, then worked to convince isolationist constituents to change their minds. “Nixon had given them his best judgment,” Farrell observes, “and they thanked him for it.”

* * *

Nixon’s role in the 1952 presidential campaign was to dismantle the Democratic nominee, Adlai Stevenson, who like Voorhis, Hiss, and Douglas was a favorite of educated liberals. Nixon did so with relish. (Later, he would deride Stevenson privately in his diary as “the so-called ‘liberal intellectual’ at his worst…assuming a superior, mincing attitude…which characterizes the Georgetown, Ivy League social set to whom he is the second coming of Christ.”) Nixon answered bogus charges, fueled by the then-left-wing New York Post, of being on the take with arguably the most effective televised speech in history, baring his young family’s meager finances and persuading average voters that, in Farrell’s words, “I am one of you, and they are screwing us.” “Now,” Farrell adds, “it was Nixon who claimed a visceral connection with ‘the forgotten man,’ and the Democrats who…looked like elitists.”

Once in office, the politically aloof Eisenhower continued to deploy Nixon to “do the grubby work…that Ike deigned not to do” and then belittled him for doing it. But grassroots Republicans appreciated Nixon’s solicitude more than Eisenhower’s detachment and nominated him for president in 1960. When he lost narrowly to the glamorous, wealthy Harvard graduate John F. Kennedy and then lost by a large margin the 1962 California gubernatorial election to incumbent Democrat Pat Brown, ABC News aired a documentary called The Political Obituary of Richard M. Nixon. It featured a triumphant Alger Hiss.

* * *

Nixon vowed to quit politics but didn’t. From the beginning, he had been a fighter who as the 1960s unfolded not only stood for but also embodied the little guy whom the budding New Left movement and its media apologists disdained. Running once again for president in 1968, after several years in which rioting in the nation’s inner cities had become an expected part of the “long, hot summer” and murders, rapes, assaults, and robberies doubled, Nixon embraced “law and order.” It was the perfect issue with which to divide the New Deal Democrats. Nixon disdained racist appeals (which, as Farrell shows, had always been anathema to him), leaving that to the segregationist independent candidate George C. Wallace. But after winning Nixon was able to add Wallace’s 14% to his own 43% when running for reelection, securing a 49-state landslide in 1972. He did so by opposing busing for racial integration, while leaving popular social programs like Medicare alone and even raising Social Security benefits by 20% and indexing them to inflation. Strong public support allowed Nixon to pursue his real passion, foreign affairs. He successfully divided the Communist world, playing China and the Soviet Union against each other by establishing détente with both.

Ending the war in Vietnam, inherited from his Democratic predecessors, proved a tougher nut to crack. Farrell’s book made news when it was published, revealing that Nixon had directed campaign aides to send word to South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu in October 1968 that he should wait until Nixon was elected before entering peace talks with the Communists. True, but Thieu didn’t need Nixon to tell him that a new Republican president would try harder than a Democrat to keep South Vietnam alive. “Probably no great chance [for peace] was lost,” conceded William Bundy, a national security official in Democratic administrations who had no love for Nixon.

In a 1969 speech, the most successful of his presidency, Nixon identified his people as “the great silent majority,” a phrase that Trump picked up nearly a half century later. Who were they? “They donned their best clothes and went to church on Sunday,” Farrell writes. “They gave their time to the Boy Scouts…. They honored Old Glory. They laughed with Bob Hope and cheered John Wayne.” Starting with Nixon, increasing numbers of them voted Republican.

Nixon always described himself as a “practical liberal,” which was another way of saying (in White House counsel John Ehrlichman’s phrase) that “the president doesn’t have a philosophy.” He cared about domestic policy only to the extent that it helped him get elected—as when he ran up the budget deficit and imposed wage and price controls on virtually every product, service, and occupation to jump start growth and temporarily suppress inflation during the run-up to the 1972 election. The bill came due in the form of runaway inflation soon afterward. “The kick had been terrific,” Farrell observes; “the hangover was a killer.”

* * *

Nixon cared about getting elected for two reasons. The noble one was to do great things in foreign policy. The ignoble one was to gain and maintain power for its own sake, the summit of the career to which he had devoted his adult life. That’s the one that got him into trouble.

Having attained the presidency, Nixon couldn’t bear criticism from his enemies or the revelation of secrets, even if, as with the leaking of the Pentagon Papers, they were embarrassing to other presidents, not him. Matters came to a head when he was told in 1971 that the Brookings Institution might have a safe full of files revealing his role in thwarting the 1968 Vietnam peace talks. Nixon ordered the creation of a Special Investigations Unit within the White House—the self-described “Plumbers”—to “blow the safe and get it.” Keystone Kops to a man, they didn’t, but instead of being decommissioned their unit was shipped off to the Committee to Re-Elect the President.

Nixon lost track of what the Plumbers were doing, even though it was being done in his name. When their break-in at the Democratic National Committee’s Watergate office was foiled on June 17, 1972, he was “genuinely baffled,” writes Farrell, but “there was never a thought that they would not cover it up.” On June 23 he ordered CIA Deputy Director Vernon Walters to “call the FBI in and say that we wish for the country, don’t go further into this case, period!” How do we know this? Not just because the whole thing was recorded on tapes that eventually, in response to a unanimous Supreme Court decision, were made public. Walters also covered his backside with memos to the file, and FBI deputy director Mark Felt began meeting in a parking garage with a young reporter he knew at the Washington Post, Bob Woodward. Nixon hung on as president until August 1974, but resigned when Senator Barry Goldwater and other Republican stalwarts told him he “didn’t have a prayer” in an impeachment trial.

Politics “is a piece of cake until you get to the top,” Nixon told former aide Ken Clawson soon after he resigned. Even though you have made it, “you find you can’t stop playing the game the way you’ve always played it because it is part of you…. [Y]ou continue to walk on the edge of the precipice because over the years you have become fascinated by how close to the edge you can walk without losing your balance.”

These are cautionary words for any president, including Trump, whom left-wing opponents have been scheming to remove from office ever since declaring in angry demonstrations the day after the election that he is “Not My President!” His saving grace may be that, not having spent his life climbing the greasy pole of politics, he may not be tempted to take the desperate, foolish actions that Nixon took. If he does, he like Nixon will frustrate the hopes of the blue-collar Republicans whose votes made him president and who desperately want him to succeed.