Books Reviewed

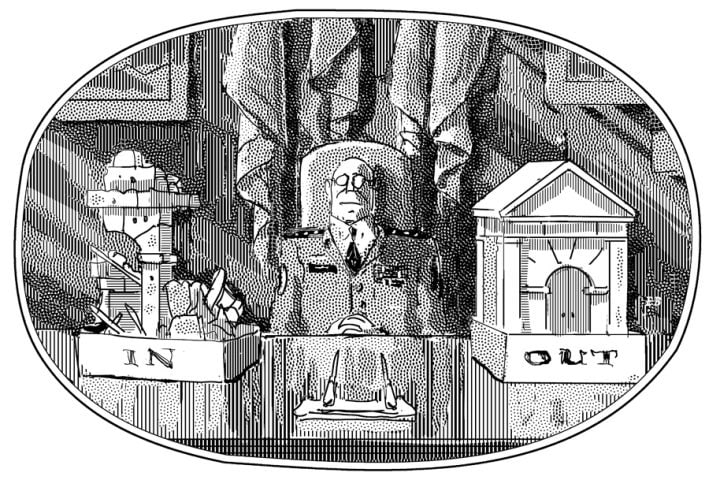

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then the reader should perhaps keep in mind three pictures while he reads the few thousand words that follow. The first picture is that of a young Syrian child lying dead on a Turkish beach after drowning in an attempt to reach Europe by small boat; the second is the news picture of a large column of Middle Eastern migrants walking into Europe that Nigel Farage’s Brexit campaign used as a campaign poster; and the third is a moving picture, Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk, which depicts in miniature the calm patriotic unity of the British people as they came together to help their army retreat from Europe as a necessary first step to defeating the German onslaught.

Two of these pictures have already had an impact on the questions discussed in the two books reviewed here. The photograph of the dead child was one important symbol in a media coverage that persuaded European (and especially German) elites to welcome refugees from war and oppression in Syria and to suppress popular resistance to doing so. But only a minority of migrants arriving over borders in violation of Europe’s rules of entry were refugees. Not even the poor child pictured was a homeless refugee; he was legally settled with his family in Turkey. He died because his father, like unknown millions of others, was seeking the better economic opportunities of life in western Europe. What therefore did the news photograph symbolize?

The second picture was criticized as a racist stigmatizing of refugees from oppression, even though it was a news photograph showing only what we had seen throughout the summer of 2015 on our television screens. Its implication that the migrants would shortly be able to settle anywhere in the European Union, though denounced as alarmist, was substantially true. What it now symbolizes is not the prejudice of nativists but how the “welcome culture” of European elites has come to be resisted—and its means of enforcing this culture to be distrusted as undemocratic and manipulative—by many ordinary Europeans.

And though judgment on the political impact of Dunkirk must be provisional, its depiction of ordinary Englishmen in uniform and in civilian dress behaving stoically and decently in desperate times undercuts the portrayal of ordinary people, in particular “the white working class,” as xenophobic bigots itching to attack migrants. Insofar as it influences popular opinion, Dunkirk is likely to undermine the post-Brexit demonization of all nationalisms, including civil patriotism, as symptoms of a dangerous and ignorant “populism.”

* * *

Two new books reach the gloomy conclusion that, whatever its past prospects, Europe’s future is likely to be bleak and turbulent. The continent, in short, is going to the dogs. All that remains to be decided is the identity of the dogs, and here the two authors differ.

James Kirchick is a neoconservative American journalist who has been reporting from Europe for almost a decade (we were colleagues at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty). In The End of Europe, he portrays a continent plagued by a long list of overlapping problems: the weakening of the political center and the mainstream parties, the rise of populism, the United Kingdom’s Brexit vote and its potential to weaken European unity, the Euro crisis, the threat from a revanchist Russia, a failing commitment to liberal democracy, the growing appeal of Vladimir Putin’s authoritarianism, an aversion to a robust foreign policy and a corresponding unwillingness to spend money on defense, a disturbing rise in anti-Semitism in western Europe (even more than in eastern Europe), and a migrant crisis that at times resembles a non-military invasion by predominantly young Middle Eastern and African men who are also largely Muslim. These crises interact with each other to produce a more general crisis of political, moral, institutional, and even civilizational self-confidence. And—what especially matters to America—they weaken Europe as a strategic and economic partner for Washington in global affairs.

Douglas Murray, a conservative British writer and deputy editor of the London Spectator, would accept most of Kirchick’s analysis—Brexit is an exception—and would sympathize with his robust candor. Murray’s The Strange Death of Europe shows, however, that, like the hedgehog to Kirchick’s fox, he knows one big thing: the migration crisis is far more dangerous than all the others. It poses an urgent existential threat to Europe’s future, and how it happened suggests that neither the European Union nor national governments have much of a clue how to resolve it. Both Kirchick and Murray are sharply critical of how the German and Swedish political and media establishments have tried to conceal evidence of migrant responsibility for an increase in rapes and other violent crimes. Despite occasional overlapping agreement, however, the two writers end up on different sides of a large political gulf.

* * *

In addition to his varied multinational palette of topics, Kirchick has a broad theory of what has gone wrong across the continent: a rising populism with authoritarian overtones has undermined both liberal democracy and European integration that between them had created a peaceful Europe inhabited by citizens enjoying unprecedented rights and security.

To make this case, he examines the specific politics of seven countries and the European Union itself in eight chapters sandwiched between an introduction, “The European Nightmare,” and a conclusion with recommendations, “The European Dream,” dealing with the overall crisis. In recent history, of course, the dream actually preceded the nightmare. But the wider drawback to Kirchick’s method is that it’s a messy blend of ideological preaching and national reporting in which the former sometimes distorts the latter. One French reviewer, though favorable to the book, complained that the chapter on France ended up being mainly about anti-Semitism, which is an important component of France’s crisis but far from the whole of it.

This is not a discrediting point, but it’s not a minor one either. Most of Kirchick’s analysis, especially the chapters on Sweden, Greece, and Germany, are well-informed, balanced, and written in a briskly readable prose. Their overall picture of Europe is written from the standpoint of a Cold War liberal disappointed at what has gone wrong in the last decade or two. This is a realistic starting point, and the author’s particular insights are worth knowing and largely persuasive. His account of Germany’s reflexive anti-Americanism, for example, is a shrewd look at an underestimated phenomenon in European politics. Anti-Americanism has joined with pacifism and commercialism to shape a new German national character that makes the country a less reliable partner, particularly in European energy politics. When Kirchick stands back and reports or analyzes coolly, he is excellent.

* * *

But his desire to press home his larger ideological case of populism versus liberalism distorts his reporting in other cases. His account of the current politics of Hungary and Britain, for instance, is closer to propaganda than to journalism. The chapter on Hungary—which depicts Prime Minister Viktor Orbán both as ambiguous on anti-Semitism and as the harbinger of a new European authoritarian populism—raises too many sensitive issues to deal with fairly in the limited space available here. But the chapter on Brexit and Britain, though equally one-sided, is more comically so.

Among other charges, it expresses a kind of baffled horror that the British people should have rejected the advice of a long list of international eminent persons and expert institutions; it greatly exaggerates the role of Nigel Farage in the campaign, suggesting that he emerged from it as the main victor; it gives the second share of credit to London’s former mayor Boris Johnson whom it depicts as an insincere politician who misled the voters on serious issues; it blames a 500% increase in “hate crimes” on the result; it predicts that Brexit will result in the break-up of the U.K.; it forecasts a serious economic downturn even in the short term; and it treats the decision to leave the E.U. as a withdrawal from the defense of Europe and the decline in U.K. defense spending as evidence of Britain’s withdrawal from world influence.

None of these accusations withstands scrutiny. To respond in reverse order: Britain is a leading member of the only serious European defense organization, NATO, and one of the three members that meet their 2% of GDP spending pledge. (Kirchick thinks other NATO members will catch up. Well and good. But until then should he treat Germany, Spain, Italy, etc., as withdrawing from European defense and world influence?) The various short-term economic setbacks predicted by Brexit’s “Remain” opponents, whom Kirchick echoes, have yet to appear. The U.K. economy is now projected to grow by 1.7% next year, which is the third highest growth projection in Europe.

As to the break-up of the U.K., that too has been postponed. The Scottish Nationalists lost ground in the most recent election and have now been compelled to announce that they will not seek a second independence referendum until after Brexit has been decided. It is hard to imagine that if Britain leaves the E.U., the canny Scots would choose independence without any firm prospect of a sugar-daddy in Brussels. In these regards Kirchick has been discomfited by a publishing schedule that caused his predictions to reach us late, like light from dead stars.

The rise in “hate crimes” turns out to be (1) a large percentage increase from a small base—a regular weekly average of 63 crimes to 331 in Brexit week—that subsequently fell again; (2) an increase not in crimes but in the number of complaints phoned in to a police line; and (3) to consist mainly of such crimes as spitting, catcalls, and jostling if the courts decide the complaints are crimes at all.

* * *

As for “who won Brexit,” Boris Johnson was certainly an important voice for the “Leave” campaign because he was a political Big Beast. It would be odd if he chose the Leave side from motives of ambition, however, since like everyone else, he thought it would lose. And if his speeches sometimes exaggerated the Leave case, they pale alongside then-Prime Minister David Cameron’s warnings that Brexit would cause a world war and a depression. (“Which comes first?” asked a television interviewer to loud audience hilarity.) Nigel Farage was also an important factor in the victory of Brexit because he was an early, brave, and eloquent advocate of a cause that, while it was treated as unrespectable and even lunatic by most elite institutions, including the BBC, consistently scored above 30% throughout 40 years of opinion polling. But by the time of the campaign his advocacy—which alienated as well as attracted voters—was one voice in a choir of many, including front-benchers from both parties, two former finance ministers, and even representatives of the Great and Good such as Edward George, former governor of the Bank of England, and historians Noel Malcolm and David Starkey. Electorally Brexit was passed not by fringe voters but by a coalition of most Tory voters and by about 40% of Labour supporters. Since Brexit, popular support for Farage’s U.K. Independence Party has drained away to mainstream parties and Farage himself has left politics, at least temporarily, for the media.

Finally, how can Kirchick be so firmly disapproving of the British for rejecting the advice of eminent persons from banks, Brussels, and global institutions such as the International Monetary Fund when, as he himself describes, these various elites have mishandled the Euro crisis, the Greek crisis, the banking crisis, the E.U.’s democratic deficit crisis, and, above all, the migrant crisis? One cannot dismiss the popular suspicion of experts without first examining the success rate of expert advice.

All in all, it is hard to see that Brexit was an angry populist upsurge at all. It looks far more like a rational decision, after a vigorous democratic debate, to retrieve sovereignty from a remote bureaucracy that was governing badly.

* * *

And that raises the second problem with Kirchick’s overall approach: populism and liberal democracy, though common terms in the higher journalism, are slippery ones. If “populism” describes a movement that is personalist, rooted in a leader-principle, hostile to the “regime of the parties,” and based on blending Left and Right in a vague new synthesis, as political scientists have traditionally argued, then the most successful populist leader in Europe today is President Emmanuel Macron of France. He is never described as such, however, and the E.U.’s Jean-Claude Juncker has even hailed his election as the beginning of the end of populism. That is because Brussels and establishment opinion generally approve of his ideological bent, which embraces such familiar policies as multiculturalism, open borders, a banking union to underpin the Euro, and a kind of militant born-again Europeanism. They regard populism as a threat to these policies and so they ignore the populist aspects of the Macron victory. As generally used, therefore, populism is not a neutral term but a “boo” word employed to discredit or to indicate disapproval.

Liberal democracy, too, can be an example of verbal shape-shifting. Kirchick writes at one point that democracy has to be intertwined with liberalism in order to be truly democratic. That would be true, as it used to be, if liberalism meant such things as free speech, free assembly, a free press, etc. How can an election be free without free speech to enable discussion of the issues?

In recent years, however, liberalism has come to mean the proliferation of liberal institutions—the courts, supranational bodies, charters of rights, independent agencies, U.N. treaty monitoring bodies, etc.—that increasingly restrain and correct parliaments, congresses, and elected officials. This shift of power was questionable when these bodies merely nullified or delayed laws and regulations. But more recently they have taken to instructing democratically accountable bodies to make particular reforms and even to impose them on the entire polity through creative constitutional and treaty interpretation. Their decisions have concerned a wide range of official powers from welfare rules and gay marriage to regulations on migration and deportation (of, among others, convicted terrorists). Liberal democracy under this definition becomes the undemocratic imposition of liberal policies (often with the silent cooperation of liberal legislators), and if unchecked over time, it devolves into a new political system that Hudson Institute scholar John Fonte calls “post-democracy.”

Once we take this (fairly major) development into account, it becomes possible to reach a definition of populism that is not simply a way of abusing a political party or set of proposals. Political scientists are belatedly realizing this. As the Dutch political scientist Cas Mudde said some years ago: “[P]opulism is an illiberal democratic response to undemocratic liberalism. It criticizes the exclusion of important issues from the political agenda by the elites and calls for their re-politicisation.” That is true and important of no issue more than of the massive flood of immigrants into Europe that began in the 1950s and that may now be reaching a crescendo.

* * *

Douglas Murray’s new book is a comprehensive examination of mass non-Western immigration to Europe and a treasury of practical, political, and philosophical reflections on it. It is also a book with the controversial and (to some) outrageous thesis that most European countries will cease to be European by mid-century. It answers in the negative the question that opens Christopher Caldwell’s Reflections on the Revolution in Europe (2009): “Can Europe be the same with different people in it?”. Indeed, Murray begins his book: “Europe is committing suicide.” How does he justify such an inflammatory judgment?

He begins by tracing the stages in the postwar migration by which we went from a Europe composed of countries that (outside a few regions like the Balkans) were largely monocultural to one in which (outside central Europe) large non-Western immigrant communities live alongside their native-born neighbors. The raw figures of this demographic change are remarkable. London was an overwhelmingly “white British” city in 1955; by 2011, white British people accounted for only 45% of its population. What U.N. demographers call “replacement immigration” had changed the population and character of a major capital city and, of course, it changed the country, too.

It began very modestly with guest workers coming over on a temporary basis to fill labor shortages in German car factories or in Britain’s National Health Service. But they never went home and were soon joined by family and friends, who now had points of contact when they arrived in a strange German or British city. As the news spread that jobs were to be had at wages far above those in the developing world, the trickle of immigrants increased.

Legal attempts to regulate immigration were made by governments, but the rules were quite liberal since politicians felt guilty about keeping out poor people from former colonies, and besides, the immigrants learned to game the system. So a modest but relentless rise in immigration continued, not much hindered by official controls, until Tony Blair became prime minister in 1997 and adopted a policy positively encouraging migration—to boost economic growth, official documents argued; to swamp the Tories electorally, said a Blair policymaker. The new policy accelerated the transformation of Britain into a multicultural society with racial and religious tensions; terrorist murders, bombings, and beheadings; physical attacks on gays in East London; the extraordinary epidemic of the rape and sexual grooming of underage girls by Pakistani Muslim gangs in Rotherham and in two dozen other provincial cities; hostile demonstrations against British soldiers returning from Afghanistan; an estimated (by the British Medical Association) 74,000 cases of female genital mutilation by 2006; the occasional honor killing; and excellent restaurants.

* * *

Most migrants, and in particular most Muslims, are entirely innocent of the crimes mentioned above, but opinion polls show that substantial minorities think them justified and that larger numbers have firmly illiberal attitudes to anti-Semitism, homosexuality, blasphemy, and apostasy. Other European countries—in particular Germany, France, and Sweden—have experienced much the same. But their problems have become more severe and more widespread since German Chancellor Angela Merkel “welcomed” a million Syrian refugees into Europe and accepted many hundreds of thousands of them with suspect refugee credentials.

How could this happen? Murray’s initial answer is that it happened because we told ourselves lies to justify each stage of the process. There aren’t many migrants and it’s no big deal; that argument showed an unawareness of the demographic truth that large percentage increases in small numbers add up to a lot quickly. (Think compound interest.) They contribute more to the economy and the welfare state than they receive; in fact immigration does not raise a nation’s per capita income and it imposes heavy net fiscal costs on national and local treasuries. They will rescue the welfare state and pay for our old age; in fact migration provides little or no alleviation of social security costs (see previous point) and because migrants have children too, it increases them long term. They make our dull societies more diverse and thus more exciting; but many people like home to be familiar and comfortable, and cultural change can be destructive as well as vibrant. They’ll soon assimilate to our liberal values. Really? How soon? For how long should we be prepared to accept a rise in rapes or restrictions on free speech as a price worth paying for those better restaurants? And what if the newcomers don’t assimilate but demand that the “native” community does so instead by, for instance, demanding sharia or blasphemy laws? Recent British governments have shown themselves not unwilling to move in such directions. Given population trends, as Murray points out, they will have stronger incentives to do so in the future.

* * *

A reduction in overall numbers of immigrants, incidentally, would naturally reduce incentives for identity politics and multiculturalism, and increase those for assimilation. If a minority amounts to 1-2% of the population, it realizes (without thinking much about it) that it can’t demand the wholesale reconstruction of society to reflect its own cultural values. Over time it will likely reach an easy accommodation with its neighbors. Numbers count more than anything else in achieving assimilation; but rules favoring economic skills and cultural similarities help too. America still has the chance to implement such policies—most recently in the bill introduced by senators Tom Cotton and David Perdue. For most of Europe it’s probably too late.

Murray deconstructs the official optimistic scenarios on migration rather like a psychiatrist diagnosing the delusions of a patient with strong defense mechanisms. He shows, for example, how the British government would trumpet the favorable statistics of an interim report on the economics of migration and then bury the unfavorable ones reached reluctantly by the final report. He advances the debate most effectively, however, by going out to meet the migrants in camps and border-crossings and the politicians in parliaments and offices to hash out the moral arguments surrounding the claim of non-Europeans to enter Europe over local resistance. Does the Syrian civil war justify lifting all restrictions on refugees? He finds that Syrians are not popular with most inmates of the refugee camps. An Afghan refugee explains that since Afghanistan has also had a war for five years, it’s unjust that Syrians should be preferred to him and other non-Syrians.

* * *

But if we admit all refugees fleeing civil wars or, more ambitiously, all migrants fleeing misery of every kind, won’t that overwhelm the recipient nations, create social conflict, and unjustly impose a more dysfunctional reality on the citizens of European countries? Indeed, might it not abolish Europe altogether? Murray finds that a liberal-minded German politician, wanting to affirm both the moral necessity of welcoming people in misery and the ability of Europe to remain itself après le déluge, points out that there’s no contradiction because the migrants have stopped coming. When Murray responds that this is because Merkel has stopped them by reaching an agreement with Turkey to keep them there, the politician won’t really listen to this explanation. He prefers to keep himself morally innocent by refusing to consider the likely consequences of his policy.

When those consequences become unavoidably obvious, what will he say? Faced with this question, some maintain that this replacement migration was inevitable anyway and so not blameworthy. But Japan’s stricter immigration controls refute that claim. Others argue, like a Swedish minister, that the natives should feel grateful because, in Sweden’s case, a rich Kurdish culture will fill the vacuum of a nation that has no culture at all “except silly things like a mid-Winter festival.” That seems insulting to, among others, Ingmar Bergman and August Strindberg and a case of blaming the victim as it applies to all other living Swedes. Yet if he had met resistance, wouldn’t he have told Swedes they were racist and undeserving of sympathy—the terminal where all excuses end up?

* * *

What explains this mixture of delusion and determination that underpins Europe’s migration policies and its suicidal openness to its own destruction? Murray answers this question with a series of philosophical reflections on the flimsy moral character of political and intellectual leaders in the modern West. He sees a tiredness and listlessness in Western civilization that arises ultimately from the 19th-century German Biblical scholarship that persuaded many Victorian intellectuals that their faith was in vain. That loss of faith was a fierce and terrible experience for individual believers like the poet Arthur Hugh Clough, but it has since spread in a diluted and organic form to the social classes who run society and shape its moral messages. Most do not realize consciously that their absence of belief has undermined, claims Murray, the founding image of our civilization, God on the cross, that powered the building of Notre Dame cathedral, the music of Bach, the sculpture of Michaelangelo, and the poetry of Milton, Keats, and Tennyson. But that absence has dried up the sources of energy and weakened the virtues, secular and religious, of our civilization in all its pursuits. It becomes vulnerable to guilt and shame for its historical crimes and still more so for its great achievements. Our governments and political parties, which deal in lesser works, are accordingly timid, apologetic, masochistic, and indecisive in the face of threats from outside. They pass the buck to the future.

These are speculative arguments—though powerful ones—and they gain some force from the grace of Murray’s writing. (They ignore, to be sure, the considerable contribution of the Greek philosophical tradition to the West.) One might say, in the light of his religious ambivalence—he is a “cultural Christian” or “Christian agnostic”—that he writes like a fallen angel. He also sees that the death of God has opened the way to any number of Mammons and Molochs—to the religion of art, the worship of food, the sanctimony of NGOs, or the great political faiths of the 20th century, Communism and Nazism, snakes that are still “scotched…not killed.” European politicians believe they can construct a new kind of polity in which rigid faiths, ancient nations, and the possessors of armed doctrines will gradually meld into a single peaceful community under the flag of universal values.

* * *

Neither author is optimistic that this will happen, though James Kirchick is slightly less pessimistic. Though he acknowledges that over-ambitious E.U. policies are at the root of such deep crises as the migrant crisis, and perhaps because he attaches relatively modest significance to its democracy deficit, he harbors some hope for an E.U. revival and suggests reforms to achieve it. Considered abstractly, the reforms Kirchick recommends are reasonable, reminiscent of the reforms successive U.K. governments urged on their European partners without success, and his boosting of NATO is better and more necessary than that. But the specific E.U. reforms are inadequate to the size of the challenge. Charles de Gaulle’s decentralized “Europe of Nations,” which Kirchick recommends, will not be advanced by moving powers from one Brussels institution, the Commission, to another, the Council of Ministers. And as the pre-Brexit negotiations showed, the E.U. establishment is unwilling to consider reforms a great deal more modest than that.

It may be that instead of moving from a nightmare to a dream, Europe has gone in the other direction. Kirchick writes at one point that the citizens of Europe have never enjoyed such rights and security as in the European Union. That gets the timing slightly, but significantly, wrong. European countries enjoyed their golden age of economic growth and political stability between about 1948 and 1974—and it continued as a somewhat less golden one until 1989. Successive treaties turned the European Economic Community into the European Union with more member-states, greater centralization, and some federalist great leaps forward like the Euro and Schengen, which have the smell of utopia about them. The citizens of Europe have enjoyed lower economic growth and less political stability since then. The 2008 financial crash and other external factors played their part, but non-European countries recovered from them more quickly than Europe. It is clearly doing something wrong.

Kirchick should now consider whether the answer is not “more Europe,” but a radical decentralization of the E.U. within a larger but more liberal economic bloc composed of Europe and the U.S. (which, after all, has been guaranteeing its security all this time). A “Big Bang” project like that might be the only way to spark the revival of Europe and the West that he rightly seeks.

Even so, a revived Europe would still run slap-bang into Douglas Murray’s one big thing. It is, he thinks, likely that Europe will just drift further and further towards its own replacement by an anti-Europe built on different cultural foundations. Those Brits, Germans, Swedes, and Frenchmen who can’t adapt to the new national culture will retreat like hobbits to rural backwaters. Eurabia will prevail.

Murray holds out only one faint glimmer of hope. Throughout this history the great majority of ordinary Europeans, Brits in particular, were at every stage opposed to continuing high levels of immigration. They had to be deceived, repressed, and ignored in order for the policy to prevail as it did. They, in turn, have come to distrust and rebel against their deceivers; hence “populism.” As a further twist, their rulers have come to despise and even hate them as a recalcitrant obstacle to their own dreams of utopia and status. This class resentment downwards has been evident in Britain since the Brexit referendum in the open and bitter attacks by Remainers on both the poorer and less educated voters and on the idea of democracy itself. It’s repellent, but it’s also an unwilling tribute to the power of ordinary people in a democracy. As 1984 predicted,

“If there is hope,” wrote Winston, “it lies in the proles.”

If there was hope, it MUST lie in the proles, because only there in those swarming disregarded masses, 85 per cent of the population of Oceania, could the force to destroy the Party ever be generated.

We’ll see.