Books Reviewed

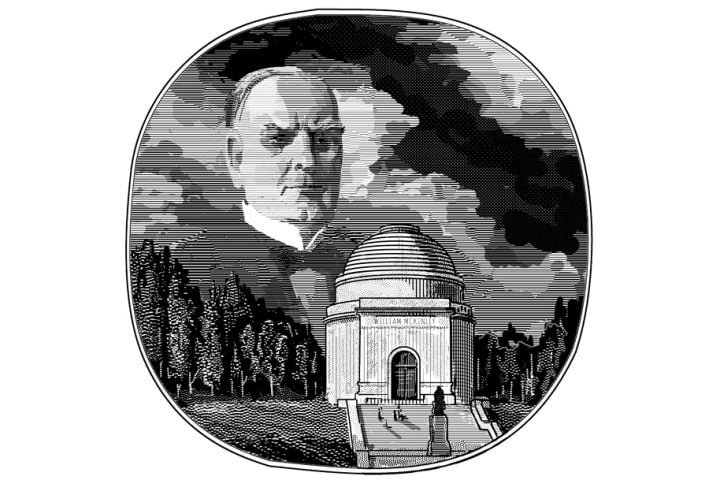

For most Americans, the 25th president is largely unknown, overshadowed by the rambunctious man who replaced him, Theodore Roosevelt, and by William Jennings Bryan, the man whom he twice defeated for the White House. Yet after winning in 1896 one of the nation’s five great realigning elections (the others were in 1800, 1828, 1860, and 1932), William McKinley devoted his presidency to leading America into new prominence on the world stage.

The list of modern McKinley biographies is comparatively short. There’s Margaret Leech’s 1959 Pulitzer Prize-winning In the Days of McKinley. It was followed four years later by William McKinley and His America from University of Oklahoma professor H. Wayne Morgan and then by University of Texas historian Lewis L. Gould’s The Presidency of William McKinley in 1980, part of the “American Presidency Series” from the University Press of Kansas. In 2010 R. Hal Williams of Southern Methodist University also drew attention to McKinley with his Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan, and the Remarkable Election of 1896 from the University of Kansas’s “American Presidential Elections” series. Still, the man and his achievements remain underappreciated.

* * *

Now Robert W. Merry, a former Wall Street Journal reporter and later managing editor, executive editor, editor-in-chief, and president of Congressional Quarterly, has joined this hardy band of biographers and put his considerable talents to work expanding the public’s understanding of McKinley’s pivotal role in American history.

Merry’s previous book, the masterful history A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent (2009), argued that Polk was a consequential president who made America a continental nation by winning the war with Mexico and settling a long-standing dispute with England over Oregon’s border. On the domestic side, he slashed tariffs and reformed the banking system, then retired after one term (and died four months later)—America’s only effective president between Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln.

In his new book, Merry tackles McKinley in the same revisionist spirit, painting a persuasive picture of the president who launched the United States on the path to becoming the 20th century’s dominant nation. As a young man he was a war hero, enlisting as a private at the Civil War’s start and ending the conflict as a brevet major, with three battlefield promotions for conspicuous bravery that included surviving two suicide missions. When recommended for the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism at Antietam, he discouraged his comrades from pursuing the matter, saying he was only doing his duty.

He soon became a skilled legislator, serving in the U.S. House for nearly 12 years from a swing district in Ohio, then as now a key state in national elections. He earned a reputation in Congress for hard work, adroit management of legislation, and a genial manner that earned him respect across the aisle in an era of intense, bitter partisanship. (By comparison, today’s Washington looks like both parties are roasting marshmallows and singing “Kumbaya” around a campfire.) Even when—in a practice common to both parties in close contests during the Gilded Age—the Democratic majority threw him out of Congress in May 1884 after he had won re-election in 1882 by only seven votes, some of his fiercest Democratic adversaries voted to seat him in a show of respect. McKinley’s popularity caused Speaker of the House Thomas B. Reed to complain, “[M]y opponents in Congress go at me tooth and nail but they always apologize to William when they are going to call him names.”

* * *

Merry also draws attention to McKinley’s admirable family life. His colleagues and the public saw the loving care he showered on his wife, Ida Saxton, a fragile, nervous woman who developed epilepsy after the couple lost both their children, one daughter at the age of just five months and the other before her fifth birthday.

Before his ascent to the presidency, “The Major” (as he preferred to be called) was a two-term reform-minded governor from 1892 to 1896. Though Ohio’s chief executive had few real powers, McKinley passed an ambitious agenda of tax reform, railroad safety measures, and infrastructure improvements. In his second term, his efforts at promoting labor peace and providing relief for those hit hard by the 1893 depression cemented his reputation as a Republican champion of the workingman.

McKinley became the GOP presidential nominee in 1896 as an outsider, besting the party’s bosses in state conventions where he out-organized the establishment and defeated the front-runner, Speaker Reed (“Czar Reed” as he was called, and not just behind his back). The Major then went into a raucous general election that he hoped to fight on the issue of trade protection. Instead, he was forced to battle Bryan on the currency issue, on which McKinley had a mixed record. Bryan’s surprise nomination and oratorical skills propelled the Nebraska populist into the lead in the late summer and early fall. But by mid-September, McKinley had found his voice on the currency question and began turning the issue among urban industrial workers. His message of sound money, protection, and national unity made him the first presidential candidate since Ulysses S. Grant in 1872 to win more than 50% of the popular vote. His victory kicked off a 36-year period of Republican dominance during which the GOP lost power only when it split briefly in 1912.

* * *

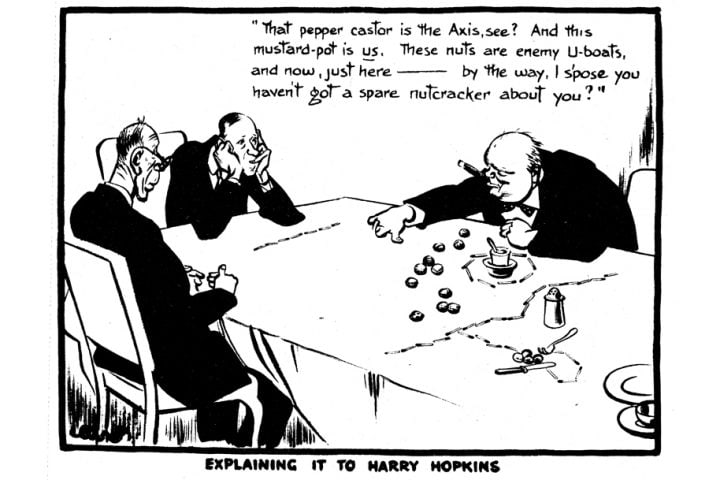

As president, McKinley began building the modern American navy; acquired the “Gibraltar of the Pacific,” with the annexation of Hawaii; and won the Spanish-American War, giving the U.S. possession of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam while granting Cuba its independence. What’s more, McKinley’s “Open Door” policy provided equal trading rights in China and kept the Middle Kingdom from being carved up by world powers. He helped to forge the “special relationship” with Great Britain that’s been a key element of American foreign policy ever since.

When McKinley took office in 1897, the deep depression the country had endured for almost four years under Democrat Grover Cleveland quickly dissipated. Part of the reason for this recovery was that McKinley wasn’t Bryan. Bryan’s Free Silver rhetoric had terrified business leaders while The Major approached the currency question in a reassuring way that united labor and capital, restored confidence, and renewed the animal spirits of the nation’s business community.

Merry shows how McKinley codified this sound money policy with the 1900 Gold Standard Act, after deftly deflating sentiment for bimetallism in much of America by proving no other major power supported an international agreement for currencies based on both gold and silver. The guarantee of a sound currency also attracted investment from home and abroad that was needed to build factories and railroads, and open mines and new agricultural regions. The mild inflation America experienced—after gold strikes in Alaska, South Dakota, and elsewhere had increased the money supply—contributed to prosperity’s return.

He called Congress into early session in 1897 to reinstitute the Republican tariff policy. This was the main issue The Major had advocated during his years in the House, earning the nickname, the “Napoleon of Protection.” Here Merry demonstrates his skill as an historian for the McKinley who occupied the White House was different from the one who had served in the U.S. House. Economists still argue how much the Republican policy of high tariffs contributed to the nation’s economic growth in the Gilded Age. Although Representative McKinley favored protectionism, he thought business interests were often too greedy with their tariff demands. He voted, for example, against a tariff bill sponsored by his mentor, Ways and Means Committee Chairman William D. “Pig Iron” Kelley, because he thought it too generous for domestic manufacturers. McKinley also championed removing tariffs from imported consumer staples like sugar and coffee, and from materials for industrial production that were not domestically produced.

* * *

But by his inauguration, the new president believed the country’s prosperity increasingly depended upon selling its goods abroad. So he put a stronger emphasis on the principle of reciprocity: America would reduce its trade barriers to countries that removed obstacles to the sale of U.S. goods in their markets. President McKinley acted on this belief by backing the Dingley tariff, a moderate measure sponsored by Congressman Nelson Dingley of Maine. Though the bill was manhandled by high-tariff senators who attached 872 amendments raising rates for specific goods, McKinley signed it in late July 1897 and then appointed a special commissioner to negotiate reciprocal trade agreements.

He also moved against the industrial trusts, expanded civil service reform, and worked to maintain labor peace. He enjoyed cordial relationships with both parties in Congress and so strengthened and broadened the chief executive’s powers that Lewis L. Gould has called him “the first modern president.”

By the end of his first term, the country was prosperous and at peace after the short and popular war with Spain. Running on the slogan of “A Full Dinner Pail,” McKinley won reelection with the (then) biggest popular margin in history, demolishing Bryan again. He had served just over six months of his new term when an anarchist shot him on September 6, 1901, at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. He lingered until—despite days of upbeat bulletins from his physicians—dying on the 14th.

* * *

Merry ends his volume by asking why historians have passed over or belittled McKinley’s accomplishments. Some of the critics argue that he was simply in the White House when events altered America’s course. Others attribute his successes to the able men he gathered around him. Some give the credit to presidents who followed up on the initiatives McKinley began.

And of course, there’s Theodore Roosevelt, whom Merry calls “impetuous, voluble, amusing, grandiose”—words that would never be applied to The Major. T.R., he writes, “took the American people on a political roller-coaster ride, and to many it was thrilling.” But to Merry, it was T.R.’s reticent, gentlemanly, patient, focused predecessor who is the true author of the American Century.

Even Roosevelt knew the greatness of the man who had picked him as his running mate, having previously rescued him from political oblivion by making him assistant secretary of the navy, a post without which T.R.’s future rise would have been impossible. As William McKinley was laid to rest in the Canton, Ohio, cemetery, the entire cabinet was seated before the receiving vault, many openly weeping. The young new president stood a few yards apart, reluctant to sit with his colleagues for fear he, too, would lose control of his emotions. The country experienced a moment of grief it had not felt since Lincoln’s assassination, and would not experience again until John F. Kennedy’s. Readers of Robert Merry’s excellent book will better understand why at that instant America so deeply loved its fallen chief.