Books Reviewed

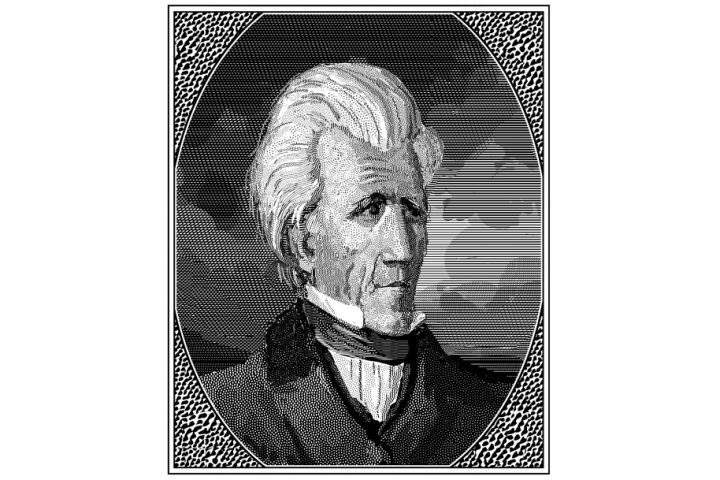

The devotion Andrew Jackson once enjoyed is hard to overstate. By 1859, he was second only to George Washington in townships named in his honor. Celebrated as the champion of ordinary Americans against corrupt elites, Jackson feared that American national government was especially vulnerable to capture by the creeping, undeserved influence of a privilege-seeking few. Yet, as McGill University historian J.M. Opal shows in Avenging the People: Andrew Jackson, the Rule of Law, and the American Nation, he was more complicated than his popular image suggests. For much of his life he embodied frontier America’s tension between civilization and barbarism, where Enlightenment liberalism clashed with the pre-modern politics of honor and glory-seeking.

Commemorating Jackson’s 250th birthday in March 2017, at the Hermitage, his estates in Tennessee, Donald Trump identified Jackson’s martial virtue as a key to his success. He fought in the Revolution, but his rise to national prominence came after his victory at New Orleans (1814-15) at the end of the War of 1812, where “his ragtag—and it was ragtag—militia…drove the British imperial forces from America,” observed Trump. We can hardly conceive today of a militia, let alone a “ragtag” one, defeating a foreign power on American soil, and elevating its relatively obscure commander to the presidency.

* * *

Modern titans are often admired for lucrative industrial or technical innovations; Jackson was admired for his manliness and bravery. He couldn’t stomach the obscurity of plying a trade and living modestly in the Waxhaws, a frontier Carolina territory, during the 1780s and ’90s. The Battle of New Orleans?where he led a vastly outnumbered American force to victory?gave him, Opal writes, “all the glory he had ever wanted,” convincing “a broad mass of people that God had directly intervened to save his most favored nation” through Jackson’s leadership. His attraction, argues Opal, was rooted in Americans’ desire for justice?and to conquer and punish?rather than in a commitment to democratic republicanism and its humane ideals.

Jacksonians “raged at the moral chaos of the world,” where scalpings were answered by bloody campaigns of vengeance and calls for total war. Jackson was a throwback. His righteous indignation had a tribal flair, characterized by anger against perceived injustices, whether from the British or American Indians, or from personal slights. His military and political conquests, especially against the Indian tribes of the southeastern U.S., were driven by a desire to revenge violent assaults against white settlers on the frontier. His brand of justice, Opal believes, was unrestrained by law.

* * *

The Federalists in the national government had failed in the early 1790s to placate Indian tribes through treaties and payoffs. The Cumberland was besieged by fear and violence: “everyone knew family members who had spent time in the [wartime] forts or whose loved ones had died in horrifying ways,” writes Opal. With little loyalty to the legal order that failed to protect them, frontiersmen engaged in repeated campaigns of retribution. Through first-hand accounts, Opal shows Jackson clashing with the Federalists over law’s purpose—justice through vengeance versus Enlightenment due process.

Jackson thought the Indians “had no concept of ‘the law of Nations’ and only sought to commit ‘Murder with impunity.’” Treaty-making with them was largely ineffectual and meaningless. By 1793, the worst year of frontier violence, fearful settlers vacated their homes and relocated to makeshift forts. Opal thinks it probable that Jackson defended, late that year, a widely circulated pamphlet calling for Indian extermination.

Doubling down on their largely ineffectual commitment to the rule of law, the Federalists admonished frontiersmen for not trusting in the “arm of society,” which had “put an end to the bloody havoc of distinct times and savage places.” Jackson, as attorney general for the Southwestern Territory, excused vengeance seekers by painting a legal veneer on their vigilantism. He argued, for example, that an entire Indian nation could be punished if they refused to extradite suspected murderers hiding in their territories.

Opal too quickly dismisses as legal manipulation Jackson’s commitment to the right of self-defense. By arguing that frontiersmen ought to be allowed to choose how to administer justice and security in what was virtually a state of nature, Jackson made a defensible case for a certain sort of rule of law, born of natural right.

But Jackson was a controversial glory-seeker, immoderate and unrefined. His sensitivity to personal slights overshadowed his devotion to the Declaration of Independence’s natural rights teaching. In 1806 he killed a man in a duel for insulting his wife, nearly getting killed himself in the process. He met public criticism by defaming his victim, claiming he had “rendered no ‘essential service to the Publick’” and speculated in the slave trade. That same year Jackson was convicted of assault and battery for a separate incident and almost entered a second duel. As Opal demonstrates, the “quarrelsome and contentious” Jackson fell far short of Aristotle’s or anyone else’s ideal of a gentleman.

* * *

Opal uses Jackson’s vengeful nature to build an explanatory narrative of his life, including his presidency. Jackson’s fitness for office was often questioned in terms of his potential for dictatorship since his deepest political passions were satisfied by the relative freedom of military command. Yet, as president, he was painfully constrained by intermediary institutions, especially by the Whigs in Congress.

Jackson’s complicated love of just punishment is best illustrated by Opal’s analysis of an obscure episode, in which he operated as judge, jury, and executioner over traitors during an 1818 Florida campaign. Two British soldiers had been detained for inciting Indians to attack American settlers. Standing “alone in a Florida wilderness that no European nation had effectively claimed, in the half-light of a war that no European nation had officially declared,” Jackson prescribed a set of ad hoc legal procedures to try and punish the prisoners. Jackson wrote evocatively of the episode as exemplifying the slow but just power of men to exact retribution and ensure heaven’s vengeance on earth.

Given Opal’s argument that Jackson was motivated by the love of vengeance—his “sense of justice was the rule of law”—Jackson’s insistence on some semblance of legal process is curious. Opal notes that he justified his approach through the “law of nations,” which prescribes that “any individual of a nation making war against the citizens of any other nation, they being at peace, forfeits his allegiance, and becomes an outlaw and pirate.” But why should an outlaw and pirate deserve any semblance of procedural justice, however rudimentary?

Confusion about the relative weight of Jackson’s commitment to law and the “right” of vengeance is shot through Avenging the People and maybe through Jackson himself. Opal is strongest when he shows how figures like Jackson were caught at a crossroads of early American political development. They seem most at home seeking reprisal and glory in courageous moments against enemies. At the same time, they were conditioned by a liberal tradition that sought to conquer glory-seeking through the rational administration of law.

Opal’s confusion might have been avoided had he taken seriously Jackson’s arguments as president. “There is no question,” he asserts, “that the presidency changed Andrew Jackson, perhaps more than it had his predecessors,” but he dwells little on Jackson’s words, and leaves us in the dark about Jackson’s intellectual development. He neither analyzes the constitutional arguments surrounding the national bank controversy, nor Jackson’s response to the Senate’s censure after his unilateral removal of the Federal Bank deposits in 1833.

* * *

Jackson invented a new presidential doctrine, in which the president exercises greater authority in controlling and removing a treasury secretary than Congress, because the president “is the direct representative of the American People.” Opal ignores this. I suspect Opal deemphasizes Jackson’s constitutional and legal arguments because he assumes they do not explain his presidential behavior. He mentions Jackson’s famous veto message, with its defense of the “humble members of society” against the self-dealing rich and well born, but he overlooks Jackson’s attempt to bring this theme to the defining center of American politics.

Jackson’s attempted reordering of the separation of powers to make the president, rather than Congress, the steward of the people’s interests was a watershed moment in the development of American political thought. Avenging the People is a missed opportunity, not only for understanding Jackson on his own terms, but for understanding the thread that links him with current cultural and political debates. Instead, Opal distances Jackson from us. For him, Jackson’s novel view of sovereignty, as the right to heed one’s passions in the defense of natural rights, is rightly consigned to the dustbin of history.

But another kind of Jacksonianism remains alive today in Donald Trump’s claims to embody “real people,” unjustly victimized by the smug privileged. Like Jackson, Trump speaks of fair economic opportunity and the virtues of honest labor; like Jackson, Trump points to an idealized republican past, in which self-sufficient, locally-oriented families prospered without moral or economic meddling from external forces, be they elites, immigrants, or powerful commercial interests. Did Jacksonianism constitute a reasonable movement, as Trump has said, to “reclaim the people’s government from an emerging aristocracy?” Or was it simply motivated by a hatred of certain classes of “elites?” Opal’s focus on Jackson’s thirst for vengeance neglects these questions.

Jackson organized and mobilized groups of Americans, not so much for their superior numbers or “whiteness,” but for the way of life to which they aspired: self-sustaining, sober, unpretentious, and directly connected with the fruits of their labor. These alone represented the “real people” deserving of the Constitution’s blessings. Trump appealed to this Jacksonian spirit at a campaign rally in May 2016, declaring that “the only important thing is the unification of the people—because the other people don’t mean anything.” For Jacksonians like Trump, America’s spiritual renewal—its republican virtue—depends upon the “sober pursuits of honesty industry,” the virtues associated with coal mining and construction work, for example. These virtues not only prepare the ground for the perpetuation of communities, but foster the republican citizen’s sense of self-worth and confidence.

Jacksonian Democracy, wrote historian Marvin Meyers in 1957, constituted “an appeal to an idealized ancestral way” that defended the virtues of “simplicity and stability, self-reliance and independence, economy and useful toil, honesty and plain dealing.” While Opal sheds much light on Jackson as a glory-seeker, he almost totally ignores Jackson as a republican statesman. His otherwise stimulating book too-easily reduces Andrew Jackson’s motives to his inordinate and bloodthirsty passions.