Books Reviewed

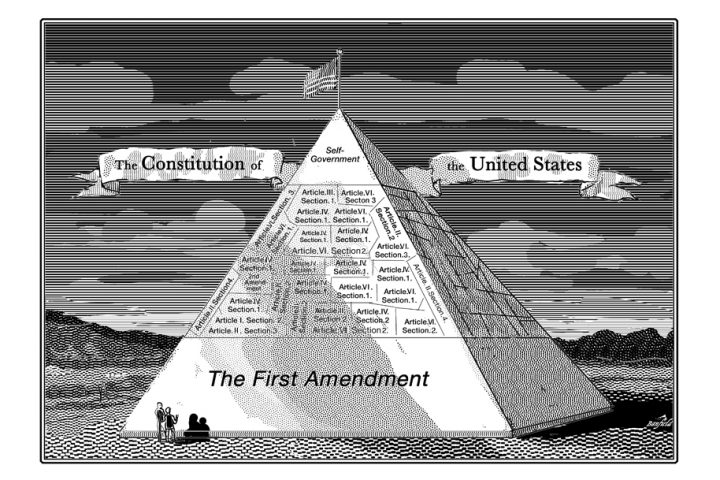

Whatever else might be said about American exceptionalism, free speech’s status in American law really is exceptional. Although free speech is affirmed in international documents such as the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, there it is typically qualified by other imperatives, or even openly subordinated to other goods. The First Amendment, by contrast, is absolute: “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” How can any American patriot not exalt such rights?

Floyd Abrams certainly does in The Soul of the First Amendment. Abrams’s eminence as a First Amendment lawyer goes back to his work with Alexander Bickel on the brief for New York Times Co. v. United States (the Pentagon Papers case) in 1971, and continued with his winning argument for Senator Mitch McConnell in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010). Abrams’s book recounts the bipartisan triumph of what might be called free-speech absolutism, from its first stirrings a century ago to its dominant position on the Supreme Court today, all the while contrasting American law with British or European. Though the First Amendment’s language applies strictly to Congress, Abrams accepts the incorporation doctrine that extends its prohibition to the states. He asserts, as well, that it binds the executive and judiciary, not just the legislature.

* * *

In fact, he argues that Bridges v. California (1941), in which the Supreme Court reversed California’s holding a newspaper in contempt for its comment on a pending case, is “the first and most authoritative rejection in the United States of English law governing expression” and “nothing less than a new declaration of American independence.” By contrast, he quotes a dissent by Justice Stephen Breyer from a 2014 decision that struck down campaign finance limits, in which Breyer contended that the First Amendment protects not only individual rights “but also the public’s interest in preserving a democratic order in which collective speech matters.” Abrams doubts “that the First Amendment can serve both ends.” Because the Amendment has an “anticensorial soul,” he argues, “Permitting the government—the very entity the First Amendment was adopted to protect against—to limit the speech of some would inevitably risk the rights of all.”

Abrams’s stirring defense of free speech is biographical as well as analytical. He credits Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent in Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990) with changing his mind on whether corporations can be punished for spending that promotes or opposes political candidates. This reconsideration led him to help overturn Austin in Citizens United, a development illustrating the migration of free speech commitment from the Left to the Right with the turn of the new century.

* * *

The Soul of the First Amendment deplores the courts’ acquiescence in censorship in the early part of the 20th century, noting that American jurists did their country no favors by following English precedent. Abrams criticizes the English law of libel and documents its worldwide menace to free speech, blocked here by congressional legislation and now somewhat reformed in England itself. The European Union’s “right to be forgotten,” he discovers, has led to the deletion of over half a million news articles online on topics of real public interest, particularly concerning crime. He makes the case against hate speech laws, ubiquitous in Europe but largely and blessedly, in his opinion, absent from the United States.

Only when he turns to the question of the Pentagon Papers and the recent publication of government information leaked by Bradley/Chelsea Manning, Julian Assange, and Edward Snowden, does Abrams seem at all conflicted in his libertarianism. He’s offended, as a patriot, by Assange’s description of his mission: “to safely and impartially conduct the whistleblower’s message to the public, not to inject our own nationality or beliefs.” This neutrality, Abrams believes, probably ended the lives of some overseas informants and certainly risked others, when their names were made public, and compromised undercover practices that protect national security as well. His First Amendment absolutism absolves neither leakers for violating their duties, nor editors from being held accountable in the court of public opinion for publishing classified material. Criticism for abusing rights is free speech, too.

Though Abrams’s bracing defense of free speech is particularly welcome in our censorious age, his approach is ultimately insufficient. It’s easy enough to accept the rule permitting even seditious speech absent an immediate danger of a serious evil, but is the city of Charlottesville really defenseless when white supremacist Richard Spencer and his “fine people” come to town itching to provoke a riot? What about Antifa’s commitment, expressed in word and deed, to use violence to stop speech its adherents detest? Abrams takes for granted that free speech includes expressive conduct, or to put it differently, that free speech equals free expression; but what if erasure of the line between speech and conduct has helped to paralyze us in the face of real threats from extremists? Justice Robert Jackson famously wrote that the Bill of Rights is not a “suicide pact,” a formulation suggesting that Abrams-style libertarianism has a death wish.

* * *

Timothy Garton Ash’s Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World addresses the full range of contemporary questions concerning freedom of expression, particularly those that have emerged in the age of the internet and globalization. Having established his credibility on the speech issue with his fearless reporting from behind the Iron Curtain as it was beginning to crack, Garton Ash spent years developing the framework he expounds here.

Alexis de Tocqueville long ago noticed Americans’ irritable patriotism, which in the past 50 years has been matched by most intellectuals’ irritable anti-Americanism. Garton Ash, who is British, is not entirely immune to this, but his task is actually to defend and promote American-style free speech to a skeptical world. Genuinely thoughtful and unabashedly liberal, his is a book to be reckoned with.

It begins with the circumstances of modern speech, what Garton Ash labels “cosmopolis,” the “world-as-city.” This results simultaneously from the internet, which gives a huge proportion of mankind the ability to be in touch with one another almost instantaneously, and from recent migration patterns, which have made dozens of cities around the world multi-racial, multi-ethnic, and multicultural. Both circumstances are genuinely new, he argues, noting that the modern immigrant does not leave the old country behind but often remains in daily contact with family and friends back home. Similarly, the internet has allowed the spirit of America to penetrate the daily lives of people everywhere.

Free Speech’s account of cosmopolis is not uniformly celebratory: though it instantiates the Enlightenment ideal, it also creates and enables the modern terrorist. Nor is cosmopolis egalitarian, enhancing the “big dogs” (powerful states) and “big cats” (powerful corporations). At the same time, writes Garton Ash, it enhances the “power of the mouse,” the individual user who has access to the web, to social media in particular.

Given these circumstances, he proposes an ideal of free speech, a sketch of norms rather than laws, to guide cosmopolitans’ thinking. It’s unclear whether law, based in territorial jurisdiction and dependent on the politics of a state, has the power to control the internet. China, Russia, and Iran have built digital firewalls, but this is a technical achievement, not a legal one, and its stability is uncertain. The term “free speech” carries different connotations in different tongues, making universal norms problematic, but increasingly supple machine translation and the universality of English make the language boundary porous, too. Americans have promoted global free speech to entrench our own global leadership, a sort of “unilateral universalism” as Garton Ash calls it, but in the realm of norms a genuinely “universal universalism” is at least possible.

* * *

What, then, grounds free speech norms? He offers four arguments. We need free expression, to “realize our individual humanity,” to “find the truth,” because “it is necessary for self-government” and because it “helps us live with diversity.”

The gravamen of the book is the elaboration of universal norms. As promised in his subtitle, Garton Ash proposes ten. First is the fundamental purpose, what he calls the “lifeblood” of free speech: “We—all human beings—must be free and able to express ourselves, and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas, regardless of frontiers.” It isn’t hard to recognize that his “able” is a loaded word. Garton Ash deplores the way “money howls through political campaigns” in the United States. Together with the power of big cats like Google and Facebook, wealth speaks with inordinate force—but the rest of the norms make clear that the aspiration for more widespread economic empowerment is no excuse for silencing the fortunate.

The second norm, “We neither make threats of violence nor accept violent intimidations,” rejects the heckler’s veto and the “assassin’s veto.” Free Speech calls out jihadi Muslims as the chief perpetrators of the latter. The standard he proposes would allow legal suppression of speech only when violence is “intended and likely and imminent.” His argument distinguishes speech from action, while recognizing that ideas have consequences. His working proposal for online communication, in particular for the republication by reputable websites of incendiary expression, is the “one-click-away” principle: make the Danish cartoons available, but as links, so only the reader who goes looking for offense will encounter it.

The remaining norms are “about defending the line drawn in the second principle while we exercise the right spelt out in the first.” Two, in particular, show that Garton Ash not only chronicles but endorses cosmopolis. He welcomes challenges to “all limits to freedom of information justified on such grounds as national security,” and wants to “defend the internet and other systems of communication against illegitimate encroachments by both public and private power.” The former is not as categorical as it sounds: Garton Ash agrees with Abrams that Assange’s indiscriminate leaking of informants’ names was irresponsible. The latter, too, is complicated. Garton Ash recognizes that taming private power usually requires augmenting public power. While he despises the power of money in politics, he admits that “a free market of purveyors enhances the free market of ideas.” Perhaps in the end he would be persuaded by Abrams that Citizens United is not the root of all evil.

The final principle in Garton Ash’s list is courage, circling back to the need to face down the threat of violence that would suppress free speech. He rightly invokes Justice Louis Brandeis’s opinion in Whitney v. California (1927): “Those who won our independence…believed liberty to be the secret of happiness and courage to be the secret of liberty.” Free Speech was published in 2016, before Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. While it is too soon to tell whether these events signal the end of cosmopolis or just anger at its excesses, the issues the book raises have hardly disappeared.

* * *

Compared to these bold contributions to the free speech debate, two new books on free speech on college campuses are disappointing, though in different ways. Both identify the issue of the day as free speech versus inclusion, and both insist that the two goals, properly understood, are compatible. Both are by faculty with senior positions in university administration, which perhaps explains their felt need to equivocate, though in fact both include sensible counsel on a number of issues and profess unyielding support for academic freedom. But none of the authors seems to quite grasp—as Abrams and Garton Ash do—that defending free speech today entails a willingness to face down the purported egalitarians who would suppress it.

When they wrote Free Speech on Campus, Erwin Chemerinsky and Howard Gillman were, respectively, founding dean of the University of California, Irvine School of Law, and that university’s chancellor. (Chemerinsky is now dean of Berkeley School of Law.) Both have independent reputations as scholars of constitutional law, Chemerinsky for his prolific legal commentary, Gillman for his studies of the Supreme Court and American political development.

Like Abrams, they tell the history of the constitutional law of free speech, less colorfully but more systematically. They support free speech for standard reasons—for freedom of thought, democracy, and for a free society—although it is easy to overlook that their emphasis in all three is on individual expression, not truth. They emphasize the benefit free-speech law has provided to groups once outside the mainstream in American society—blacks, religious minorities, sexual pioneers—presumably so college students come to understand that, despite what they are hearing from radical professors, free speech once served the cause of progress.

Chemerinsky and Gillman speculate as to why this is necessary. “This is the first generation of students educated, from a very young age, not to bully.” Very well, but isn’t the issue why they don’t leave behind childhood lessons, as other generations of students surely thought they were doing when going off to college?

* * *

Nevertheless, on many questions the authors’ instincts are good and their judgments sound. They clearly rebuke the British National Union of Students’ “no platform” policy of blacklisting speakers they consider to be fascists or racists and forbidding their appearance on campus—contrasting it to the policy advocated by the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley in the 1960s that insisted in principle, if not always in practice, that all political speech was welcome on campus. They refute legal philosopher Jeremy Waldron’s case for suppressing hate speech, and offer an uncritical summary of recent Supreme Court decisions that have struck down or undermined the suppression of group libel and “fighting words.” They acknowledge the experience of American universities that adopted speech codes in the 1990s: “In practice, the code was used not against the kinds of purely hateful slurs that inspired its passage, but against people who expressed opinions that others objected to.”

Free Speech on Campus lists “what campuses can and can’t do,” and the advice is for the most part sensible, if a bit complacent about the current state of the law. Chemerinsky and Gillman oppose censoring speech just because someone considers it harmful or offensive, but favor punishing speech “that meets the legal criteria for harassment, true threats, or other speech acts unprotected by the First Amendment.” They’re against the destruction of property, and the disruption of classes and classroom activities. The book supports time, place, and manner restrictions on protests so that they don’t disrupt “the normal work of the campus, including the educational environment and administrative operations.”

Does this mean that, when the next crisis comes, the liberals who govern institutions of higher learning will have the backbone and the judgment to stand up for their schools and the nobility of learning, unlike in the ’60s? The authors may prefer this course, but they do not commend it persuasively. If all learned speech is at root self-expression or “personal truth,” and what distinguishes the scholar is only “discipline,” what sustains academic freedom against the “authenticity” of its opponents? They conclude, “If we expect [the current generation of students] to fight for these [free speech] values, we must teach them these values.” But what if the young decide they prefer their equality values to their elders’ liberty values? Are Chemerinsky and Gillman willing to say that some values are better than others, so much so that the superior should be imposed and the inferior discouraged?

* * *

Sigal Ben-Porath is professor of Education and Philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, but she starts her book, also titled Free Speech on Campus, by describing a crisis involving her duties “as chair of the university’s Committee on Open Expression.” The students had occupied the administration building “demanding changes to the school’s investment portfolio to bring it into better alignment with their ideology,” and she returned to campus in the evening, negotiated for two days, took care that the students were safe overnight, protecting “the free speech of students…while the university operated as smoothly as possible.” Ben-Porath eventually persuaded them to leave so the university could consider their demands, presumably without losing face. This, she writes, is “commonplace” on campus and more typical than the dramatic incidents at other schools that garner attention in the press.

Ben-Porath seeks to construct an ideal of “inclusive freedom,” simultaneously protecting free speech, not least the speech of student protestors, while assuring first-generation college students and minorities that their dignity and opinions are respected. Despite her civil tone, she repeatedly inveighs against the insistence on civility, which she apparently thinks privileges old-fashioned manners over frank expression by the less socially endowed. She comments on the hot cases of the past year or two—Charles Murray at Middlebury, Halloween at Yale, racial trouble at Missouri, the repudiation of trigger warnings at Chicago, and Milo Yiannopoulos wherever he goes—and she seems generally to sympathize with the students or at least to portray them sympathetically, except of course the students who invite Milo. Ben-Porath admits that Erika Christakis at Yale, pilloried by students for suggesting that sensitivity had limits, was a “thoughtful commentator” who got “caught in the middle of [a] polarized debate.”

* * *

Some of her suggestions make sense, such as distinguishing “dignitary safety” (try not to hurt people’s feelings) from “intellectual safety” (it’s okay to argue). Colleges should be concerned about hurt feelings, but must foster challenging ideas. Thus, “mandatory sensitivity training for all faculty members goes too far.” She criticizes “bias response teams” for undermining “the direct relations between students and instructor, and…because of the chilling effect they have on instructors’ speech.”

But such comments are few and far between. When discussing the Middlebury case she condemns the violence against Murray, but praises the students’ arguments against bringing him to campus as serious efforts “to expand the democratic reach of free speech to groups they see as harmed and silenced, not to protect themselves within a liberal cocoon.” In reality, Middlebury’s “harmed and silenced” groups had many chances to hear other speakers at Middlebury that same semester, including Emory philosophy professor George Yancy on “Fear of the Black Body,” Vermont ACLU director James Lyall, Edward Snowden (via the internet), Time magazine’s Joe Klein, Harvard’s Tarek Masoud on “Islam and Democracy in the Age of Trump,” and Amy Goodman of “Democracy Now!”

To say in such circumstances that shouting down the one clear conservative voice is “to expand the democratic reach of free speech” is Orwellian. Fortunately, there are still liberals in the public sphere like Abrams and Garton Ash, and in the academy like Chemerinsky and Gillman, who speak up for free speech and open inquiry, however much the shortcomings of their arguments may cry out to others for more thought, more speech, and more action.