Books Reviewed

Winston Churchill, having forgotten his earlier meeting with the future president in London in 1918 when Franklin Roosevelt was assistant secretary of the navy, later remarked that meeting him as president, “with all his buoyant sparkle, his iridescence,” was like “opening a bottle of champagne”—high praise from Churchill, who drank Pol Roger and was easily satisfied with the best. In 1941, Roosevelt rejoined that “it was fun to be in the same decade with you.”

The friendship between the wartime leaders of Great Britain and what Churchill called “the great republic” began when Roosevelt wrote a letter to Churchill, who had been reappointed first lord of the admiralty in September 1939 upon the outbreak of war in Europe, signing it “Former Naval Person.” It continued after Churchill became prime minister in May 1940 with 11 meetings during the war and an exchange of almost 2,000 communications, meticulously edited by American historian Warren F. Kimball in Churchill and Roosevelt: The Complete Correspondence (1984). Publication of these messages, together with the official multivolume Churchill biography begun by the statesman’s son, Randolph, and completed by the late Sir Martin Gilbert, filled out the picture drawn several decades earlier by Churchill himself in The Second World War (1948-53). Roosevelt left no comparable memoirs, but notable books on Churchill and Roosevelt include Churchill and Roosevelt at War: The War They Fought and the Peace They Hoped to Make by the late British historian Keith Sainsbury (1994); Forged in War: Roosevelt, Churchill, and the Second World War by Kimball (1997); Roosevelt and Churchill: Men of Secrets by British historian David Stafford (1999); and Franklin and Winston: An Intimate Portrait of an Epic Friendship by American journalist Jon Meacham (2003). Subsequent volumes of wartime documents to accompany the biography, now being published by Hillsdale College Press under the editorship of Hillsdale College president Larry Arnn (Gilbert’s former assistant), reveal more about their relations.

* * *

In his new book, American banker, businessman, and philanthropist Lewis E. Lehrman, whose previous books include two fine studies of Lincoln, Lincoln “by littles” (2013) and Lincoln at Peoria (2008), draws on these sources and many others listed in his extensive bibliography, broadening the subject to focus not only on his title characters but also on contemporaries around them. In the preface he explains that, although “Churchill, Roosevelt & Company is a book about some of the principal actors and events in the most massive global war of history,” its “purposes are strictly limited to exploring some of the diplomatic, political, war-making, and peacemaking efforts of Churchill, Roosevelt, and several of their key civilian and military teammates.… [I]t attempts to cast a singular spotlight on specific people, decisions, and events.”

After explaining that Churchill had learned to leave written records of his decisions while Roosevelt declined to be pinned down by the written word, Lehrman lays out some differences between the two statesmen. He describes Churchill as better prepared than Roosevelt, more focused on the goal of winning the war, and also more honest and tenacious. Churchill was “straightforward,” Roosevelt “practiced at deception.” People thought of Churchill as a bulldog, while Roosevelt compared himself to a cat. Churchill was impatient, Roosevelt cautious. The president took his bearings from public opinion; the prime minister often got ahead of it, relying on his ability to persuade members of parliament and ordinary citizens. Churchill governed by hammering out consensus, Roosevelt “by dissimulation and surprise.” FDR often ignored his own government’s departments or worked around them by assigning power to informal agents, who were liable to end up at odds with each other or their formal superiors. Churchill could be overbearing and irritated subordinates, but “respected the constitutional traditions of the Parliament and of cabinet government.”

* * *

Lehrman’s successive chapters focus mostly on men closely associated with Churchill and Roosevelt during the war. Roosevelt had dispatched Joseph P. Kennedy, a potential rival for the Democratic presidential nomination, to be American ambassador to Britain. At the beginning of the war, Kennedy sent him a steady stream of messages claiming that Britain was finished and would be defeated by Nazi Germany. Kennedy urged a negotiated end to the war in Europe, recommending that America stay out. His defeatism encouraged isolationists in America, exasperated Churchill and his government, and led Roosevelt, who foresaw an alliance against Germany between the United States and Britain, to send William J. Donovan and William Stephenson to Europe as his secret agents, which Kennedy resented. FDR also maneuvered around Secretary of State Cordell Hull, preferring to work hand in glove with Undersecretary Sumner Welles. In time, both Kennedy and Hull resigned in frustration.

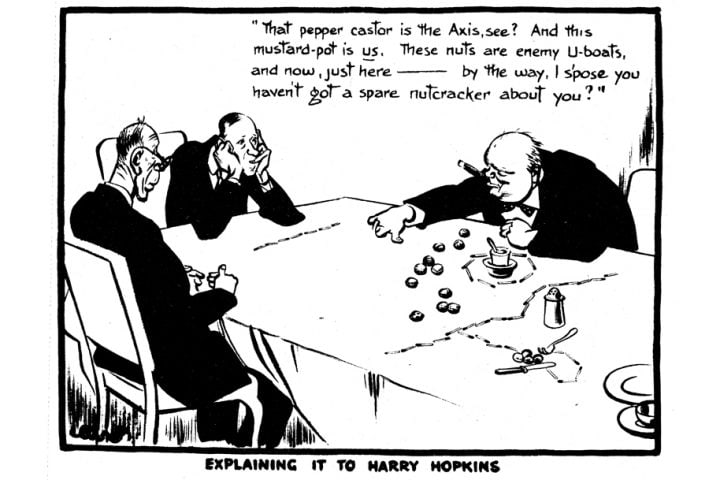

Roosevelt’s closest confidant and most important unofficial agent was Harry Hopkins, a rumpled, self-made man of the left—nicknamed “Pinko” and “Do-Gooder” by a more conservative colleague—who had served as secretary of commerce. FDR sent him to Britain in January 1941 to meet Churchill and gauge the strength of British support for the war. Hopkins, who lived in the White House, had a remarkable ability to discern “the root of the matter” and to match his counsels to the changing moods of his chief. Recognizing in him a powerful American friend, Churchill applied to Hopkins his formidable powers of persuasion and made him an ally in securing American support for Britain from a president who remained reluctant. Another of Roosevelt’s ad hoc agents, William Averell Harriman, managed to woo, bed, and eventually wed the wife of Churchill’s son, Randolph, in between sympathetic conversations over countless card games of Bezique with the prime minister.

For his part, Churchill relied on his friend the newspaper magnate Max Aitken, originally a Canadian, who had become Lord Beaverbrook. Although “known for his eccentric behavior,” he applied his energy and decisiveness to a series of crucial tasks, beginning with the multiplication of Britain’s air power. Meanwhile, perhaps taking a page from Roosevelt’s book, Churchill found a way to replace Lord Halifax, his foreign minister and chief rival for the prime ministry after Neville Chamberlain resigned in 1940, with Anthony Eden, a much firmer opponent of Nazi Germany, by dispatching Halifax to be British ambassador to the United States.

* * *

Lehrman’s sketches include important military leaders. He explains how General George C. Marshall earned Roosevelt’s confidence and the key post as army chief of staff by resisting the president’s blandishments and offering advice that was unvarnished and blunt. Quite different in character was General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who earned his position as supreme allied commander by consummate tact in knitting together in a seamless team American and British officers who had begun by regarding each other with suspicion and frank disdain.

Churchill’s endeavor to enlist America’s help in defeating Hitler had borne fruit when he and the president met in person in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, in August 1941 to announce their agreement on an Atlantic Charter—and even more when the United States declared war on Japan and Germany after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After describing the “honeymoon” between Churchill and Roosevelt, however, Lehrman moves on to the story of how divergences in the national interest of America and Britain caused the special relationship between the two countries—personified in the friendship between the president and the prime minister—to founder. Toward the end of the war, as America assumed a larger role in fighting Germany on the western front and Roosevelt aimed to enlist Russia’s help in concluding the war against Japan, the president was friendlier to the Soviet Union than to Britain, snubbing, ignoring, and even ridiculing Churchill in Stalin’s presence at Tehran.

Lehrman, whose “studies in character and statecraft” in this book mostly focus on choices, incidents, and personalities, reporting approval or disapproval from contemporaries without explicitly assigning it himself, clearly admires Churchill’s frank and courageous opposition to Hitler more than the president’s sinuous resistance to being pinned down in any permanent friendship or alliance, which Lehrman calls “Machiavellian.” As his account progresses, he focuses more on the work of Soviet sympathizers in the American administration. Drawing on historical evidence briefly made available by the opening of Russian archives after the fall of the Soviet Union, Lehrman shows how Roosevelt’s hope of being able to share leadership of the postwar world with Stalin, coupled with his hands-off indifference to the work of subordinates and inattention caused by his final illness, allowed the Soviet Union, through its agents in America and Britain, to profit more readily from its conquest of eastern Europe by bending postwar geopolitics and finance to its own advantage.

* * *

Chief among Lehrman’s company of Soviet agents is Harry Dexter White, Roosevelt’s assistant secretary of the treasury, who with like-minded associates highly placed in federal agencies diverted American aid from Britain to Russia, passed on secrets to the Soviet authorities, and favored the interests of the Soviet Union during the war and in making arrangements for the postwar world. White, “the most powerful man at Treasury except for Secretary [Henry] Morgenthau,” was chiefly responsible for conceiving and drawing up the “Morgenthau Plan,” which called for a pastoralized and de-industrialized Germany after the war was won. Hastily vetted and approved—at Roosevelt’s urging—by Britain and America at the second Quebec conference in summer 1944, the plan died a slow death by inanition, as Americans and Europeans realized over the next year, while Stalin’s Red Army occupied eastern Europe, that only resuscitation of a strong, democratic nation in the western half of Germany, including the rebuilding of her industrial might, could prevent Soviet domination of the continent. But White’s other machinations—encouraging Stalin to subvert the freedom of Poland and the Baltic nations and allowing the Soviets to deflate the new German currency after the war—were more successful in tilting the balance of power in Europe toward Russia.

Lehrman blames Roosevelt and his close associates for turning a blind eye to actions by White and other Communist agents in the American government which weakened our country at the beginning of the Cold War. In offering the reader a gimlet-eyed introduction to the cast of characters surrounding the prime minister and the president during the Second World War, Churchill, Roosevelt & Company does not shrink from calling out members of the company who should never have been allowed to be part of it.