Books Reviewed

On the Christmas Eve following Abraham Lincoln’s surprising victory in the 1860 presidential election, his archrival Stephen A. Douglas proposed two amendments to the Constitution to prevent a secession stampede. That same day, South Carolina had declared the causes that led to its December 20 ordinance of secession. So Douglas tried to preserve the American Union by making white supremacy a constitutional imperative. The first sentence of his proposed 14th Amendment stated: “The elective franchise and the right to hold office, whether federal, State, territorial, or municipal, shall not be exercised by persons of the African race, in whole or in part.” The amendment went nowhere, but his proposal to make racism truly “systemic” provides important context for assessing allegations that Lincoln was a racist.

Michael Burlingame, the Chancellor Naomi B. Lynn Distinguished Chair in Lincoln Studies at the University of Illinois, Springfield, takes the title of his book from a little-known eulogy of Lincoln that Frederick Douglass delivered on June 1, 1865. In his most famous speech about Lincoln, delivered 11 years later at the dedication of the Freedmen’s Memorial in Washington, Douglass would describe Lincoln as “preeminently the white man’s President.” In his 1865 eulogy, however, Douglass called Lincoln “emphatically the black man’s president, the first to show any respect for their rights as men.” The 1865 speech proved to be a trial run for the later one. But with Reconstruction’s gains for black Americans all but gone as former rebels reasserted political control in Southern states, Douglass presented Lincoln in 1876 as a president whose “unfriendly feeling” toward black people helped him maintain the support of loyal white Americans in a manner that both saved the Union and liberated black slaves. Black citizens in the waning months of President Ulysses S. Grant’s presidency needed whites to see that a Lincolnian pursuit of national policies could advance the interests of both whites and blacks in the face of growing resistance in the South. Burlingame shows that Douglass’s two speeches, while seeming to draw opposite conclusions regarding Lincoln’s bona fides as a friend to black people, affirm Lincoln’s commitment to their liberation.

* * *

The Black Man’s President is a veritable compendium of Lincoln’s interactions with black Americans, stretching from his early adult years in Springfield to his 50 months in the White House. Most of the book’s chapters chronicle the surprising number of his presidential contacts with black people. Ranging from White House staff to black activists and leaders near and far, they addressed matters such as black employment in the federal government, colonization, enlistment of black troops, and voting rights. Burlingame showcases Lincoln’s meetings with Douglass, a vociferous critic of the first few years of Lincoln’s presidency but, like many citizens black and white, a man eventually won over by Lincoln as a man—“of human goodness and nobility of character, no better man than he has ever stood or walked upon the continent”—and as a politician: “measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, [Mr. Lincoln] was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.”

Burlingame appends a useful chapter that rebuts the claims of Lincoln’s racism, often based on his use of the n-word and controversial comments he made during his 1858 debates with the categorical white supremacist Stephen Douglas. Considering Lincoln’s words in the context of the occasion and audience, as well as the explicit racism of fellow Republicans and abolitionists, Burlingame marshals sufficient evidence to show that Lincoln believed “that Black Americans were not inferior—adeptly using his political capital and cunning to achieve equality in a land that was far less tolerant than he.”

* * *

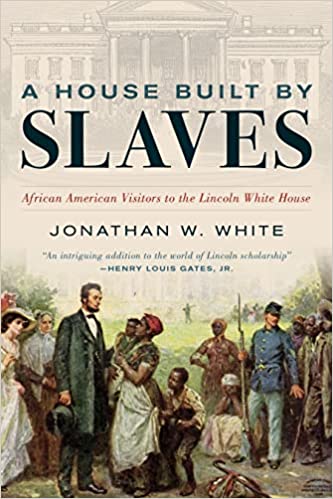

In A House Built by Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House, Jonathan W. White, a prolific historian and professor of American Studies at Christopher Newport University, offers a similar account of Lincoln’s many favorable meetings with black Americans. His approach, however, relates the experience of these meetings as conveyed in the black visitors’ words. (The index highlights their names in bold—four score and seven by this reviewer’s count.) White shows how the Lincoln White House, in becoming an unprecedented venue for numerous black audiences with the president, served as a daring symbol of their prospects for social and political elevation at a time when sympathy for black Americans was not a majority sentiment even in the North.

The reader learns about New Year’s receptions that were no longer exclusively white affairs, Lincoln’s hosting of black diplomats from the newly recognized country of Haiti in 1863, and fundraising picnics by black congregations permitted on the White House lawn in 1864. These events met with outrage, broadcast in newspapers across the country, as whites saw the president as too accepting of black people. In 1864, a Maine newspaper described one such reception as an “insane craving for negro equality, forbidden by the decrees of the Almighty”—a sentiment repeated in other Northern newspapers expressing disgust over the president’s promotion of “social equality between the white and black races.”

* * *

A signal contribution of White’s book is his account of the manifold ways that black Americans did not wait to be treated with equal dignity and respect but constantly pressed for their rights as citizens and took the opportunity of social functions and private audiences provided by Lincoln to make their presence and demands known as American citizens. “I felt big there,” declared Frederick Douglass, after his first private audience with the president in August 1863, a meeting that Douglass initiated. He quickly learned that Lincoln as a man and as a politician was a friend to black people. Douglass had been impatient with Lincoln, especially regarding the equal employment, payment, and promotion of blacks in the military after his issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. But after meeting with Lincoln, he came to understand the constraints under which Lincoln operated as an elected official: “He [Lincoln] knew that the colored man throughout this country was a despised man, a hated man, and he knew that if he at first came out with such a proclamation [regarding retaliation for mistreatment of black prisoners of war], all the hatred which is poured on the head of the negro race would be visited on his Administration.”

These constraints can be summed up in a word: consent. What White and Burlingame demonstrate is the challenge that Lincoln faced in promoting the rights of black Americans in a society where government answers to the governed. This happens through voting and through the public sentiment that expresses itself between elections. Their books amply illustrate the difficult social and political environment of Lincoln’s day, and how readily politicians not interested in refining and enlarging the public views sought to exploit existing and widespread color prejudice.

Both Burlingame and White argue that black Americans like E. Arnold Bertonneau and Jean Baptiste Roudanez helped persuade the president to lobby for the right of black Americans to vote, especially in Louisiana, where Reconstruction looked most promising. What Lincoln preferred to call the “restoration” of federal authority began taking shape before the war ended, and Bertonneau and Roudanez called personally to the White House on March 3, 1864, after their initial entreaties to the military governor of Louisiana George F. Shepley and Union General Nathaniel P. Banks fell on deaf ears. Lincoln heard them out, reminded them that the franchise was not a military question but chiefly a state matter, but added that if expanding the vote to blacks became essential to ensuring loyal governments in former rebel states, then he could support it as a military necessity. Like his rationale for issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln’s endorsement of extending voting rights to blacks could be justified “solely upon political necessities” and not simply on “moral grounds.” His visitors understood and left satisfied that the president had engaged in honest dialogue about the political fate of blacks in America.

* * *

Lincoln would make time for other black visitors who sought his influence on behalf of the vote so they could protect themselves politically once the war was over. Ten days after his meeting with Bertonneau and Roudanez, the president wrote to Michael Hahn, Louisiana’s newly elected governor, that the state convention should enfranchise “some of the colored people…for instance, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought so gallantly in our ranks,” for those citizens “would probably help, in some trying time to come, to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom.” Burlingame and White offer copious details of his meetings with blacks from Louisiana, as well as North Carolina and Virginia, that indicate their efforts bore fruit: in addition to private letters to Hahn and Banks, Lincoln publicly called for black Americans to be granted the vote, most famously on April 11, 1865, shortly before he was assassinated.

That said, as early as August 1863, the president had already been corresponding with General Banks about a new constitution for Louisiana that would not only recognize the Emancipation Proclamation but also provide “[e]ducation for young blacks.” This was not unconnected to his later suggestion that “the very intelligent” be granted the vote. Douglass remarked that the president “never shocked prejudices unnecessarily,” appreciating after Lincoln’s death the great risk he courted whenever he made public overtures in the direction of improving the social and political lot of black Americans. That risk, Burlingame argues, cost Lincoln his life.

Lincoln’s welcoming attitude, demonstrated by his unprecedented acceptance of black Americans, reflected his conviction about the fundamental equality of all human beings. He once said that America was built on the idea of “the progressive improvement in the condition of all men everywhere.” That progress required the able articulation of men who, like Lincoln, sought to align the practices of government more consistently and comprehensively with the principles declared at the very founding of the United States. Lincoln argued for an inclusive path toward that progressive improvement, a path laid out in a principled fashion that would be necessary if blacks were to gain their civil and political rights. His steady, persistent arguments for recognizing all humans’ inalienable rights prevented a very different resolution of the controversy over black slavery. Without Lincoln’s principled statesmanship, the nation would not have witnessed a “progressive improvement” but rather white supremacy firmly ensconced as the engine of American politics, and black slavery well on its way to legalization in all the states.

* * *

With the passage of Stephen Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, Lincoln believed that the greatest obstacle to eliminating slavery in the United States was not slave-owning Southerners but complacent white Northerners seduced by Douglas’s notion of “popular sovereignty” and its ostensible neutrality on the slave question. Douglas believed that whites at the local level—whether in the states or federal territories—had the right to decide the question without interference from Congress. In other words, whether the enslavement of black people would expand or diminish in the United States would be determined not by a majority of all American citizens but by a small majority of white settlers in the territories.

In March 1860 Lincoln framed the issue starkly:

They tell us that they desire the people of a territory to vote slavery out or in as they please…. Caring nothing about it, they let it come in, and that is the end of it. It is the surest way of nationalizing the institution. Just as certain, but more dangerous because more insidious; but it is leading us there just as certainly and as surely as Jeff. Davis himself would have us go.

What made Stephen Douglas’s “don’t care” policy so “insidious” was that for slavery to become national, no politician north of the Mason-Dixon line needed to endorse it. Simply get white citizens in the free states not to care if black slavery expanded into federal territory. Once slavery was accepted as a constitutional right there, as the Supreme Court declared in Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857, its legalization in the free states would follow in short order. Lincoln’s consistent defense of the natural rights of blacks throughout the 1850s led to a presidential election in 1860 that presented a clear choice for white Americans about the future of freedom and slavery in the country. It also acted as a stress test of the constitutional order, one where a significant minority of white Americans were unwilling to accept the outcome of an election. “And the war came.”

In Ralph Ellison’s posthumously published novel, Juneteenth (1999), the protagonist observes, “He’s making somebody mighty uncomfortable because he’s got them caught between what they profess to believe and what they feel they can’t do without.” Lincoln understood this to be the predicament of white Americans in antebellum and Civil War America. As Burlingame and White ably show, Lincoln spoke and acted with black Americans in ways that made many white Americans uncomfortable. He risked their discomfort while fighting to save an American Union he hoped would be “forever worthy of the saving.” As he said to an Ohio regiment heading home in August 1864, “When you return to your homes, rise up to the height of a generation of men worthy of a free Government.” To be worthy of a free government, Americans needed to believe that deserving freedom for themselves meant protecting the freedom of fellow citizens regardless of color. Lincoln preached to the nation what he had practiced in the White House in hopes that a house built by slaves would serve as a beacon of liberty to all coming generations.