Books Reviewed

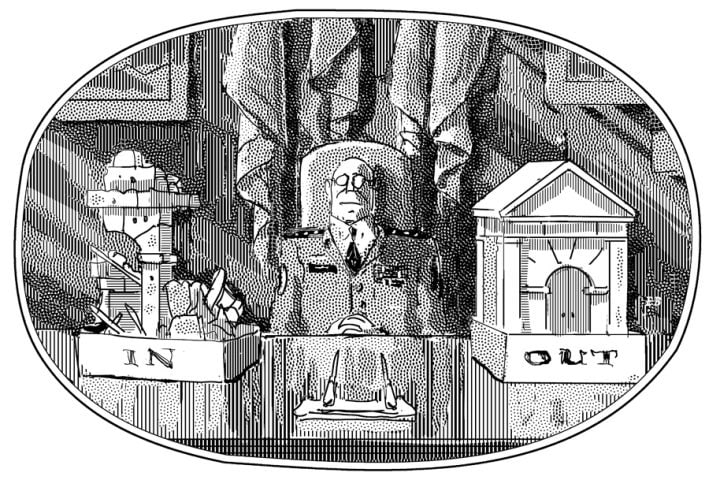

For a businessman it must be frustrating to sit at the Resolute desk in the Oval Office and realize how unbusinesslike is the government surrounding you.

President Trump issues executive orders, which can be stayed immediately by some obscure federal judge in a deep-blue state. He can ask the State Department to unwind the Iran treaty, but his own employees drag their feet. He negotiates with scores of congressmen who, like cats, enjoy being stroked but immediately go their own ungrateful way. And don’t even purr.

No wonder he is said to be frustrated. Some of these vexations come with the job. They are consequences of the very constitutional system he has sworn to preserve, protect, and defend. Separation of powers, an independent judiciary, and checks and balances are meant, in part, to frustrate over-ambitious office holders and their schemes.

These same constitutional devices, however, are also supposed to lead to better, more deliberative laws, judicial decisions faithful to the Constitution, and a chief executive who can energetically, to use The Federalist’s word, enforce the law and protect national security. They are supposed to produce good government, in other words.

But good government has not been forthcoming lately. This isn’t the Constitution’s fault. Its commands have been disregarded, or reinterpreted, and its operations distorted for so long and to such an extent that it functions as our frame of government much less reliably than you might think. Though still to be reckoned with, the capital-C Constitution yields far too often to the small-c (“living”) constitution, another word for government as usual in Washington, D.C.—that is, government as we have come to know, fear, and resent it since the 1960s.

When Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton concluded the political deal that put the nation’s capital on the banks of the Potomac, the District of Columbia was partly swampland; and to the metaphorical swamp it is returning. Trump is right about that. Some buildings, mostly monuments, museums, and memorials, continue to rise high above the muck, but others seem to inch lower every year.

Consider the Capitol, and the biggest legislative accomplishment it has seen since the 1980s, Obamacare. How could Congress have passed Obamacare the way it did in 2010—on a party-line vote, with corrupt bargains aplenty, and unconstitutional (big-C) provisions galore—and then turn around and fail to repeal the law the way it did this summer? “To lose one parent,” observed Oscar Wilde, “may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.” To have passed President Obama’s health bill may be regarded as a grave constitutional misfortune. But to fail to repeal it smacks of constitutional carelessness. Democrats were responsible the first time, Republicans the second. The former didn’t tell the truth about Obamacare, the latter (some of them, at least) about their oath to repeal it. How then are the American people supposed to reassert control over their own government, if neither party can be trusted?

* * *

But a breakdown of understanding helps to generate the loss of trust. Congress ties itself into a knot first on health care and now on tax reform in order to comply with its own arcane budget rules. Then, if decades of experience can be relied on, it will promptly toss all the budget and procedural rules aside—no separate authorization and appropriation bills for each department—in order to pass a hurried Continuing Resolution to fund the whole federal government at last year’s levels (which were carried over from the year before, and the year before that…), plus or minus a few billion here and there. Edward Luce of the Financial Times puts it nicely: the Congress “is a sausage factory that has forgotten how to make sausages.”

It isn’t just Congress. Across the government, the derelictions of duty mount, along with the sense that nobody here knows how to play this game. Few seem to miss good government because few remember it any more.

Trump’s executive orders valiantly reversing Obama’s can themselves be reversed by the next president. Organic problems in the executive agencies themselves, which cry out for legislative remedies—above all, the agencies’ propensity to combine legislative, judicial, and executive powers in the same set of hands, “the very definition of tyranny,” as Madison warned—go untreated.

Early in the administration, Steve Bannon called for “deconstruction of the administration state.” That was a political bullseye, but it can’t succeed without a serious effort to reconstruct constitutional government at the same time. Now is the time to think not only about draining the swamp but about keeping it drained, through a wise system of dikes, dams, and pumping stations. To prepare such reforms, perhaps we need a presidential commission to examine all the leading elements of our era’s constitutional and political dysfunction.