Book Reviewed

People going into politics often proclaim that they “want to make a difference.” The story of Adolf Hitler suggests this may not always be a wonderful idea. Probably no individual has ever made a greater difference, for ill (though Stalin and Mao have claims). It is true that the circumstances of Germany’s defeat in 1918 made the country ripe for an extremist takeover. But Hitler’s dark rise to power, and the way he wielded that power, were personal and unique. In that sense, the man himself “owns” World War II and the Holocaust. He believed in, planned, and enacted them both.

It is natural, therefore, that people have never stopped asking “what if” questions about Hitler. What if he had never lived? Or what if he had not been refused admission by the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna?

Here is my “what if” question: On October 29, 1914, my great-uncle, Gillachrist Moore, was a 20-year-old British officer under German attack in the First Battle of Ypres. “In this war one is always under fire…” he wrote to his sister, “By Jove one will know how to enjoy life if one pulls through this…I’m sure my men would appreciate a jolly old cake.”

On the same day, in the same battle, the 25-year-old private Adolf Hitler took part in that attack. He, too, wrote a letter. Shells “uprooted the mightiest of trees and covered everything in a horrible, stinking yellow-green mist,” he said. On the road, Hitler and his comrades came under heavy fire.

One after another of our number crumpled…. We charged…and were beaten back every time. There was only one soldier left from my group besides me, and in the end he fell too. A bullet tore its way through my right sleeve, but miraculously, I remained without a scratch.

A week later, my great-uncle was killed by a sniper. Adolf Hitler survived the entire war, and went on to cause the deaths of tens of millions. What if he, too, had died at Ypres, if the bullet that tore his sleeve had hit his heart? There can be no certain answer, but any biographer of Hitler needs to have the question in the back of his mind. How much is he writing about the destructive genius of one man? And how much about a nation driven collectively mad by defeat, depression, and the threat of Bolshevism?

***

Hitler: Downfall 1939–1945 is the second volume of German historian Volker Ullrich’s biography of the Führer. The first followed Hitler from birth to his 50th birthday on April 20, 1939. Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, pronounced that “[t]he Führer was celebrated by the people as no mortal man before him has ever been celebrated.” This was shortly after the illegal, unopposed, and successful German invasion of Czechoslovakia.

“Never stop—,” wrote Ullrich in Volume I, “that was the law by which the National Socialist movement and its charismatic Führer operated and gave the process of coming to and consolidating power its irresistible dynamic.” That law never changed throughout the Nazi era. Volume II traces how its logic worked remorselessly through from Hitler’s opposed, but successful, invasion of Poland in September 1939—which officially began World War II—to the bitterest of ends.

Since I have some criticisms to make of this book, I should first state that it is an impressive piece of work. Solid in its judgments, careful and thorough in its evidence, clear—though never brilliant (at least as translated into English)—in its prose, it is a book one could recommend to anyone seriously interested in the subject. It includes apt quotations from many sources and a strong sense of chronology and narrative. We learn accurately what Hitler did and said, and when.

Nor does Ullrich succumb to the temptation—strong in tackling a story so often told—of advancing unorthodox interpretations that unbalance the whole. He seems to bring a fair mind to his big subject. Even in his strong line against the upper echelons of the Wehrmacht—that most of them were much more complicit in Hitler’s atrocities than they claimed—Ullrich is usually judicious in tone. He carefully evidences, for example, the sense that the generals found it quite easy, from the start of the war, to find reasons not to protest at the work of the Einsatzgruppen, who deliberately murdered tens of thousands of Jews and other resisters as Germany forged eastward. In February 1940, General Walther von Brauchitsch murmurs about “regrettable mistakes” in Poland, but euphemistically adds that the “resolution of ethnic-political tasks necessary for the securement of German living space as ordered by the Führer” requires “unusual severe measures.”

Inchoate ideas among commanders the previous autumn that they could somehow force Hitler not to invade the East faltered. This was partly because the Nazi “never stop” rule included, above all, the conquest of Russia, and partly because it seemed to be working. Hitler had accomplished every invasion until 1939 with hardly any shots fired. Now that there was actual war, military prudence came to look dangerously like treachery. By 1942, when genocidal murder became truly industrial, and victory was turning to dust, it was often literally more than a man’s life was worth to raise any objection.

Besides—and here Ullrich’s own views become a bit confused—Hitler was proving himself a formidable military leader in the first years of the war. Although he hated and despised most of his generals, linking them with the aristocratic classes who, he believed, had failed his country, this did not lead him to disdain military affairs. On the contrary, he studied them closely, envying Stalin’s ruthlessness in purging his Red Army leadership, claiming a kinship with the common soldiers from whose number he had risen, and admiring Frederick the Great above all. He knew a great deal—the maps, tactics, history, numbers, materiel, and the men.

From October 1939 onward, Hitler was devising a bold plan for attack in the West which avoided “the old [First World War] Schlieffen plan of the strong right arm” and was designed to surround the enemy in Belgium. General Erich von Manstein’s version of this thought, upon which Hitler fastened, was to push through the forest of the Ardennes, where the Germans would be least expected. “As it happened,” Ullrich writes, “the Manstein plan was the recipe for success that delivered the Wehrmacht’s astonishingly quick victory in 1940.” Is that the right way to put it? Did the victory owe nothing to Hitler’s skilled military daring?

***

In analyzing such questions, Ullrich seems to suffer from two handicaps. The first is that he does not sufficiently recognize the disadvantage of hindsight. History, of course, is hindsight. But the best historians never forget that the actors in the historical drama cannot know how things will turn out. Apply that thought to June 1940. The turnaround from the German surrender of November 1918 to the French surrender in the same train in the same forest, with Hitler in the same chair in which Marshal Ferdinand Foch had sat, must have seemed utterly miraculous. It is greatly to the credit of Winston Churchill, who had become Britain’s prime minister in May, that he refused to be cowed by this; but it is scarcely surprising that millions of Germans, even the non-Nazi majority, were elated.

Ullrich has an odd way of pre-empting his own narrative. For instance, his chapter about the July 20, 1944 assassination plot begins by telling us that it failed. Yes, most people probably did know this before opening the book, but that is the more reason to imagine what it was like for those living through it. The effect of such pre-emptions is to distance the reader from the reality of the past.

Ullrich’s second handicap is, to put it provocatively, that he seems too ready to criticize Hitler. It is, obviously, morally essential to hold before the eye of history Hitler’s barbarous love of death and destruction. It is also factually essential, because it helps explain how the law of “never stop” drove him to fight the war even more fiercely and cruelly from the winter of 1941 when, having invaded Russia, he began to lose it. A German himself, Ullrich may feel a particular duty to warn. In his very last paragraph, he says that Hitler will “remain a cautionary example for all time” about “what human beings are capable of when the rule of law and ethical norms are suspended.”

He is right, yet the biographer inside me protests a little. Every biographer has a duty to sympathize with his subject. I do not mean, necessarily, to admire, love, or agree with him. I mean “sympathize” in its original sense—to feel with. Without such sympathy, there can be no full understanding. The biographer must enter his subject’s mind—the darker, the harder—and try to travel with him on his life’s journey.

***

I do not think Ullrich fully achieves this. He is so repelled by his main character that he exhibits the error, which Hugh Trevor-Roper criticized in British historians of the subject, of “confusing moral with intellectual judgments.” What did it actually feel like to be Hitler, to get up as he always did very late in the morning and try to fight what he almost blasphemously called a battle for Western civilization? How did he speak in conversation? In his rages, did he swear? Did he love anyone—for example, Eva Braun, his loyal and vivacious girlfriend more than 20 years his junior, whom he married shortly before they both committed suicide in April 1945? Above all, what was the relation between what he thought and what he did?

This biography stays close to Hitler. In some ways, it stays too close. It would have contributed interesting perspectives to learn how he was seen by the opponents he never met—Churchill, Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and their backroom advisers who analysed him. Through the course of the war, Ullrich stays with him, as it were, in his rural idyll of the Berghof and, increasingly, in the grim hideouts of the Wolf’s Lair, the Eagle’s Nest, and the Berlin bunker. He well conveys the backbiting of the court, the grey claustrophobia of the bombproof surroundings, and the physical transformation of the Führer from vigorous middle-aged leader to drug-diminished, stooped, trembling, bulging-eyed, prematurely old man. Yet, strangely, one does not come to know him much better.

Again, one feels that Ullrich cannot quite make up his mind. Was Hitler deluded, even crazy? Sometimes, as downfall approaches, the author seems to think so, portraying him in his “rants” as a man who cannot face the truth. Shortly before Christmas 1944, visiting the Wagner family, Hitler speaks to them of the “festival of peace” with which he, always the spoiled aesthete in his dreams of glory, will celebrate victory in the following year. This bore no relation to reality. And yet Ullrich also describes Hitler as facing the situation “realistically.” He understood, as colleagues did not, that the Allies’ demand for unconditional surrender at the Casablanca conference in January 1943 meant there could be no peace for his Germany except through victory. Ullrich is at pains to emphasize that, certainly from January 1945, Hitler did recognize that the war was lost, rather than retreating into fantasy. The author insists he retained responsibility.

***

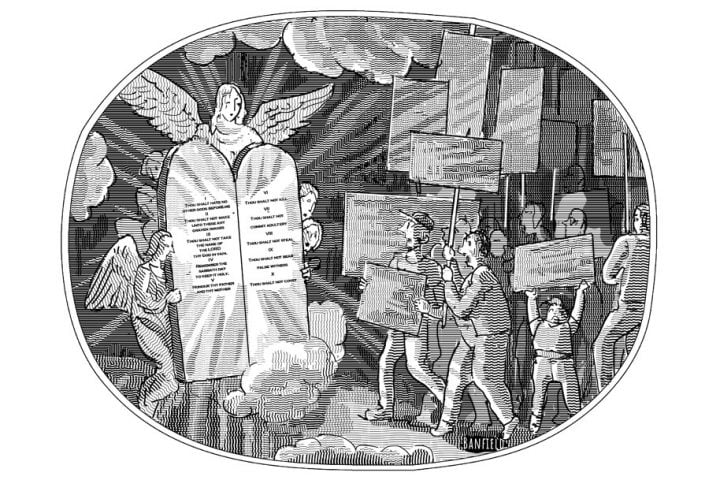

In his first volume, Ullrich quotes Joachim Fest, the distinguished earlier Hitler biographer: “He had the aura of a magician, a whiff of the circus and of tragic embitterment, and the harsh shine of the ‘famous beast.’” All true, but unlike Fest, Ullrich does not seem to recognize that such a characterization does not explain how Hitler could master, strengthen, and then destroy the largest nation in Europe, almost wiping out an entire race as he went. Might there not have been something both grander and worse in him than the bogus showman? In Milton’s Paradise Lost, Satan, heading for the Garden of Eden to corrupt mankind, wrestles with doubt, but finally decides, “Farewell remorse: all good to me is lost. / Evil, be thou my good.” This seems to have been Hitler’s decision, supported by an ideology which appeared to justify it. More than 20 years before his death, he had developed a theory of race and of history from which he derived “the German living-space problem.” The Teutons would gain world mastery if they won the East, enslaving the Slavs and destroying the Jews. The Jewish “problem” to which Hitler eventually devised “the final solution” was, in his mind, a subset of the German living-space problem. Ullrich does not sufficiently recognize that he had thought this through, and then fought it through. The failure of German elites to resist properly was the result not only of cowardice, but also of incomprehension.

In May 1944, addressing senior officers gathered on the Obersalzberg, Hitler spoke of the “life and death” struggle of the German people. “Although I have attracted the hatred of the Jews, I for one do not want to do without the advantages that hatred brings. Our advantage is that we possess a clean, organized body politic with which nobody else is allowed to interfere.” He lived and died trying to achieve this horrible idea. His life is the most shocking example ever of the dangers of consistency.