Book Reviewed

Once upon a time, America welcomed the world to her shores. Then, a group of bad people, playing to the fears of the country’s prejudiced white Protestant masses, closed the nation’s doors. Luckily, enlightened reformers, alongside the plucky children of maligned immigrants, overcame the bigots and restored America’s ideals. But the nasty people are always waiting to pounce, so we have to remain on guard against these dark forces. We are a nation of immigrants, so we must welcome the stranger the same way our ancestors were welcomed. It is the duty of every enlightened American to let in anyone who wants to come—whether through the front door or, if that’s not open, through the back.

This cosmopolitan morality tale has been circulating for over 50 years. A less ideological version of it goes back even further—to Israel Zangwill, Herman Melville, Alexis de Tocqueville, and William Penn. In the 1960s, among the American upper classes, it became almost morally compulsory to think of America in these terms. Jia Lynn Yang’s One Mighty and Irresistible Tide: The Epic Struggle Over American Immigration, 1924–1965 offers a lively retelling of the “borderless America” narrative, backed by original archival research. Yang is a highly decorated journalist—a deputy editor at the New York Times and a member of the Washington Post team whose coverage of Russian interference in the 2016 election won the Pulitzer Prize. Her book is engaging and well-written. But she completely fails to explain why the cosmopolitan dream of an open America, which was marginal for most of the country’s history, seems suddenly poised to redefine the nation’s soul.

***

I was attracted to this book because it focuses on the comparatively neglected period between the enactment of strict immigration restriction with the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, and its repeal via the Hart-Celler Immigration Act of 1965. Alas, those hoping to gain new insights into the processes that led to this shift will be disappointed. This book is the literary equivalent of colorizing a black-and-white movie: it takes an established set of facts and arguments, then adds descriptive biographical detail from archival records to bring them to life. The result is a series of engaging anecdotes but little in the way of comprehensive analysis. For example, we learn that Albert Johnson, co-sponsor of the Johnson-Reed Act, had a father who apprenticed at Abraham Lincoln’s law firm in Springfield, Illinois. Labor Secretary James Davis, another key restrictionist, sprang from a hardscrabble Welsh village and worked at a nail factory in Pittsburgh. Senator Pat McCarran, co-sponsor of the restrictive McCarran-Walter Act of 1952, was born on a sheep ranch outside Reno; and Representative Emanuel Celler of Hart-Celler fame was a German Jew from Brooklyn.

These biographical portraits are colorful. But Yang’s compulsion to moralize history leads her to offer one-dimensional, cartoonish depictions rather than nuanced portrayals. Eugenicist Harry Laughlin is a “bald, ghostly pale” man. Senator David Reed, Johnson’s co-author, is a “tall man who carried himself with great confidence, much of it unearned.” Restrictionist Senator Henry Cabot Lodge is an “argumentative snob.” Pat McCarran is described as overweight and anti-social. Those on the restrictionist side are typically hard-bitten and mean, while liberals like Celler, Lehman, and even Lyndon B. Johnson come across as full of warmth and humanity.

More generally, Yang is quite incurious about the deeper social forces which inspired the restrictionism of 1924, as well as about those which drove the liberalizing trend of the ensuing period. Reed-Johnson was the country’s first comprehensive immigration control law. It gave preference to the “Nordic”—as they were called at the time—countries of Britain, Germany, Ireland, and Scandinavia, whose former citizens were already dominant in the population. Yang accounts for the restrictiveness of this period by gesturing toward the Red Scare, the interest in eugenics reflected by the Dillingham Commission report of 1911, and the revival of the Ku Klux Klan. These are all real, lamentable things that happened. But simply focusing on the personality defects of the supposedly rotten individuals behind such trends gives an incomplete picture of how immigration policy evolved.

***

As far back as the late 1880s, social Christians like Josiah Strong had raised concerns about urban ills and inequality, which they linked to alcoholism and immigration as well as rapacious capitalism. Progressivism, influenced by the Social Gospel, introduced the idea of immigration restriction alongside a suite of reforms like temperance and workplace regulation, displacing the laissez-faire “divine will” theology of the post-1865 era. Protestants who had blithely assumed that unchurched Catholic immigrants would gravitate to Protestant churches realized with alarm that the institutional Catholic Church was booming. “Old immigrant” Scandinavians, Germans, and even many Irish, established in craft unions like the Knights of Labor and American Federation of Labor, formed a key constituency backing restriction. The Republicans won seven out of nine elections between 1896 and 1928 by appealing to these urban workers against “new immigrant” competition. The 21st-century divide between liberal openness and conservative restrictionism just doesn’t map neatly onto this period the way Yang wants it to.

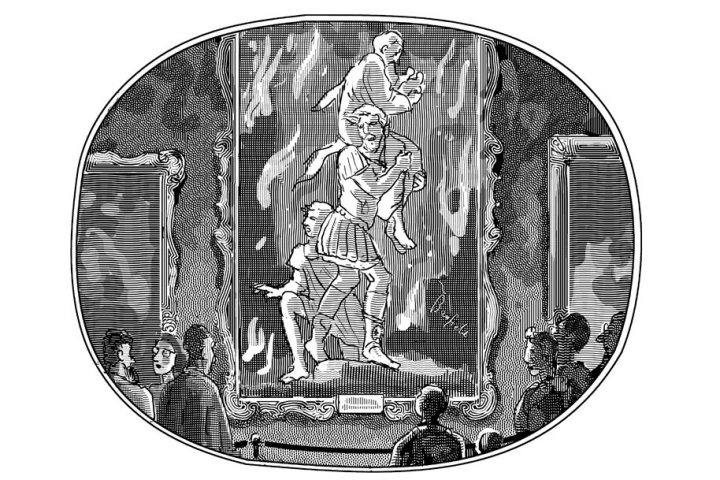

Her ensuing story of the years from 1924 to 1965 is similarly incomplete and selective. During World War II, nearly all of the public and the newspapers backed restriction. By the early 1950s, popular support for repealing restrictions was “too strong to resist,” according to Yang. But the book breezes past this extreme change in attitudes with only superficial explanation. Yang neglects to mention that the editorial positions of major newspapers rapidly shifted, from widespread support of restricting immigration on the basis of national origins in 1924, to universalism between the early ’50s and ’60s. To understand this requires more than character study or descriptions of legislative events. It requires understanding the themes I discussed in my first book, The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America (2004). To wit: liberal Progressivism and ecumenism gained currency in the 1910s, and this converted mainline Protestant elites to a pro-immigration position. The Interfaith and Goodwill movements of the interwar period, along with Modernism in the arts, fed into a wider pluralist movement that redefined Progressivism in the ’20s and ’30s. Pluralism informed the work of the National Education Association, which, between the 1930s and ’60s, successfully campaigned for schools to replace Anglo-centered nationalist works like David Muzzey’s American History (1911) with liberal texts featuring the Statue of Liberty and “immigrant contributions.” Wartime films and novels portrayed white ethnics—Italians, for example, and Irishmen—as fully American for the first time.

***

Yang does not explain any of this. Simply put, hers is not an academic book. It offers a just-so story of immigration policy as the outcome of chance events, national mood swings, and personal relationships. We learn that an important reason for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was resentment of America’s restrictions on Japanese immigration! The rise of restrictionist sentiment in the 1920s is apparently explained by World War I-era patriotism “curdling into disappointment and rage” in contrast to the optimistic Progressive era. The conclusions Yang draws from her predetermined morality tale are facile and, at times, absurd.

One Mighty and Irresistible Tide is basically a reprise of political scientist and former Democratic state legislator Keith Fitzgerald’s argument in The Face of the Nation (1996), albeit with more flair and less systematic analysis. Yet when I scanned Yang’s references, I was stunned to find Fitzgerald’s book missing. I have no doubt Yang would have cited Fitzgerald had she known about him. But this is a serious omission that more extensive research should have unearthed.

A reading of Fitzgerald’s book would show that the rise of a powerful federal bureaucracy during the New Deal and wartime enabled the State Department to become a voice for foreign policy interests pressing for a creedal, universalist Americanism. Diplomats argued that liberal democracy and capitalism, unsullied by ethnic and racial exclusion, would win friends abroad. As Fitzgerald shows, the State Department and the wider security state successfully reframed the elite-level immigration debate. Instead of ethno-culturalism versus universalism, they narrowed the bounds of policy discussion to include only rival versions of universalist Americanism. The sole question now was which universalist idea would define the “Ideal Nation”: cosmopolitan pluralism, anti-Communism, or both.

In place of Fitzgerald’s patient analysis, Yang slips in a few anecdotes about how a “McCarthyist” State Department palled around with J. Edgar Hoover while refusing to issue passports to immigrants and suspected Communists. The implication is that these anti-Communists were of a piece with nativists—a wholly misleading assumption. Had the deep state been in charge, restrictionists would have lost out much earlier. Along with other sections of the elite, they were pushing against a congressional ethno-culturalism which was able to resist due to the territorial principle of the Senate and malapportionment of population between congressional districts, both of which gave rural and Southern interests clout. Public opinion was with the congressional conservatives, but elite opinion was considerably more liberal by the 1940s.

***

The passage of the Hart-Celler Act in 1965 repealed the provisions of the 1924 act which had excluded Asians and established immigration quotas based on the ethnic composition of the country in 1920. Nevertheless, Yang laments that the bill covered Latin America for the first time, placing a numerical limit on Mexican immigration. She buys the myth, popular among liberal academics, that migration from Mexico had been seasonal before it was regulated, with Mexicans keen to return home after the harvest. Once restricted, according to this myth, workers couldn’t risk returning home and settled instead. Hart-Celler’s cap on Mexican migration is fingered as the cause of a more punitive labor migration regime that resulted in today’s pool of 11 million undocumented aliens.

In reality, permanent Mexican settlement took off after 1930 once wives began to accompany male workers. Quite rationally, they sought a better life. Temporary work schemes like the Bracero program in the ’40s did not reduce the number of overstayers but instead coincided with persistent growth in the number of undocumented settlers, as Brian Gratton noted in a 2013 article for International Migration Review (“Immigration, Repatriation, and Deportation”). Yang conveniently overlooks the small matter of rising deportations to Mexico in the 1940s, increasing into the low hundreds of thousands under Harry Truman’s presidency and cresting with Dwight Eisenhower’s “Operation Wetback” in the 1950s, which deported over a million Mexican workers in a military-style operation. Loss of political will to deport, rather than the 1965 Act, explains why the number of undocumented rose so dramatically between the 1950s and the post-1965 era.

***

A great deal is at stake here. Since 1965, as Yang readily acknowledges, skeptics like Southern Democrat Sam Ervin who prophesied that the law would lead to radical change in the country’s ethnic composition have been proven correct. In contrast, Bobby Kennedy and others who argued that geographically neutral criteria could be implemented without dramatic ethnic change were wide of the mark. For Yang, the unintended consequence of the 1965 Act is a positive: it opens up the possibility for a multicultural, post-Anglo America. She neglects to recognize that this dream is built on a deception—never a promising foundation for consensus.

In addition, events since 1989 weakened the Communist challenge to liberal democracy, which had made liberal-democratic universalism relevant for American identity as defined in opposition to the Soviets. Neoconservatism’s creedal nationalism was born of anti-Communism and was given a new lease on life by the War on Terror following 9/11, when the Right was again moved to emphasize American openness by way of contrast with a new foreign enemy. Yet this, too, has passed, and may come to be seen as the last gasp of a dying right-wing universalism. America’s Anglo-Protestant ethnocultural tradition, which Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington wrote about in his final book, Who Are We? (2004), has grown increasingly relevant. This important source of American identity has come under pressure from both demographic change and the rising assertiveness of the cultural Left, whether in its liberal-multiculturalist or radical white-bashing guise.

To be clear, this book is not a work of critical race theory that views America as an irredeemable land of white supremacy. Yang expresses admiration for American progress. Yet her left-liberal worldview shares important traits with the totalizing radicalism of critical race theory. Left-liberals and critical race theorists both exhibit a reflexive tendency to view minorities warmly and majorities suspiciously, seeking to maximize the interests of the former while weakening the latter. Both envision a multicultural nation with open borders. Both are politically intolerant toward the culturally protective attachments of conservatives; both tend to paint restrictionists in broad strokes; and both swiftly resort to epithets like “racist” or “xenophobe” to smear opponents’ motives and silence them.

***

Inconveniently for Yang’s thesis, however, we know that cultural conservatism is not coterminous with racism. Decades of research by social psychologists such as Ohio State University’s Marilynn B. Brewer confirm that attachment to ingroups is a psychologically different disposition from hostility toward outgroups. Smearing positive attachments drives them underground, whence they resurface in sublimated form—as in the case of California’s Proposition 187 (which made illegal immigrants ineligible for public benefits), the rise of the religious Right, or, more recently, the election of Donald Trump.

In the wake of Black Lives Matter activism, statues of America’s Founding Fathers have been torn down and buildings renamed in a quest to erase the Anglo-American past. In my own survey work, which I summarized in Quillette (“The Great Awokening and the Second American Revolution”), I have found that almost eight in ten white liberals favor changing the national anthem and adopting a new constitution. A majority wants history books rewritten, streets renamed, and statues toppled until “white supremacy” is defeated. Over half of “very liberal” whites want Mount Rushmore destroyed. The young are more radical than the old, and the desire for change has increased sharply since the death of George Floyd. People really think they can erase the implicit tradition of WASP identity in America, and that this will bring forth a millennium in which values, not race, define our citizens.

But they are wrong.

Ideology is becoming less relevant as the basis of American nationhood. Indeed, it is a source of division. Liberal democracy is the norm across Western countries. So too are diverse, ever-changing cities. Universalism, whether creedal or cosmopolitan, does not distinguish America in today’s post-Communist, demographically churning world. The impulse to destroy the WASP tradition began with dreamers like John Dewey and Randolph Bourne over a century ago, but only recently has it begun to wield overwhelming elite power. The problem is that the Anglo-Protestant tradition suffuses most of American history and vernacular culture. It pervades America’s “everyday nationalism,” as it’s been called, the stock of cultural minutiae and understandings that implicitly define many people’s view of what the nation is. The kind of Orwellian Year Zero editing that would be required to extirpate WASP culture and bring forth the multicultural revolution is so far-reaching that it would invariably alienate many. I’m not simply referring to conservative whites, but to many minorities who have come to identify with, and see themselves in, the country’s Anglo-European traditions, memories, and vernacular expressions.

***

To the extent the Left’s cultural revolution succeeds, it will merely result in a Disneyfied replica of actual ethnic diversity, a kind of World’s Fair writ large. Meanwhile, defenders of the old Americanism will grow increasingly resentful and insecure. The woke republic that too many liberals believe is just around the corner will be no closer to realization when the median voter is a Millennial and whites are a minority. Polarization and congressional sclerosis will be the order of the day.

A more intelligent way forward would be to cherish and adapt both the Anglo-Protestant and cosmopolitan traditions, inducting the descendants of non-Europeans into this American inheritance. Immigration should be set at a level intermediate between the desires of liberals and conservatives. This will permit multicultural Americanisms to persist, looming larger in metropolitan areas. Shorn of its cultural imperialism, cosmopolitanism can once again interweave with Anglo-Americanism in the relaxed way it did during Jia Lynn Yang’s golden period of the 19th century.