Books Reviewed

For Yoram Hazony, governments are either nations or empires. This is a more superficial distinction than Aristotle’s, for whom a regime’s purpose is paramount, whether ruled by one, few, or many. Despite its limitations, however, Hazony’s new book, The Virtue of Nationalism, is worth reading because it focuses so succinctly on what nations are, why they are good, what distinguishes nations from empires, and why Western elites’ attempt to drown nations in “liberal” supra-nationalist institutions is bad. The book presents “an anti-imperialist theory that seeks to establish a world of free and independent nations”—un monde des patries, as Charles de Gaulle would have said.

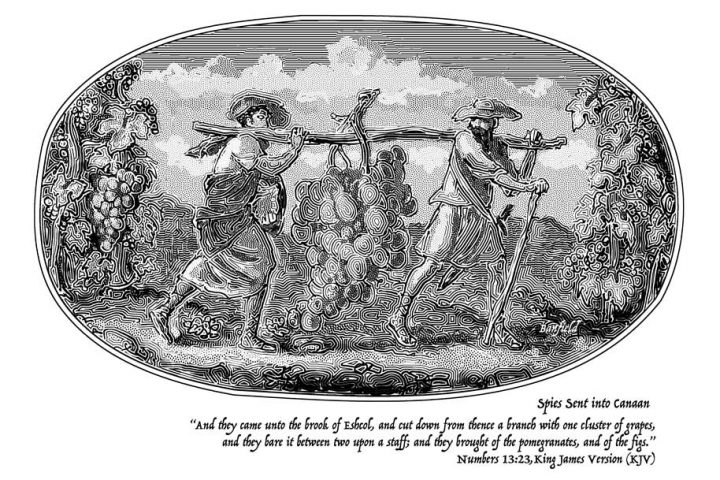

The president of the Herzl Institute in Jerusalem, and himself an Israeli, Hazony is a proud part of the prototypical nation: a people forever defined by the covenant they made with the Lord God. In quasi-Platonic terms, Israel is thus the idea of the nation. Others are nations insofar as they approach that idea. The Israelites defined themselves by their adherence to God, who shaped His people morally by giving them the Ten Commandments to instruct them in basic personal behavior. Hazony calls these “the moral minimum.” God at once endowed and limited his nation by giving them a land to be their own, while warning them—as he does in Deuteronomy 2:4-19—to “meddle not” with other peoples, whom He had also endowed with lands to be their own.

Ye are to pass through the coast of your brethren the children of Esau, which dwell in Seir…. Meddle not with them; for I will not give you of their land, no, not so much as a foot breadth; because I have given mount Seir unto Esau for a possession…. Distress not the Moabites, neither contend with them in battle: for I will not give thee of their land for a possession; because I have given Ar unto the children of Lot for a possession…. And when thou comest nigh over against the children of Ammon, distress them not, nor meddle with them: for I will not give thee of the land of the children of Ammon any possession; because I have given it unto the children of Lot for a possession.

From the beginning, then, Hazony shows that the prototypical nation was “living within limited borders alongside other independent nations…and uninterested in bringing its neighbors under its rule.” It welcomed strangers who said, as Ruth did, “thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.” God willed that Israel rule itself, as the prophet Jeremiah declared: “And their nobles shall be of themselves, and their governor shall proceed from the midst of them.” Its rulers would serve the people, because only God Himself is master of all. Having freed Israel from the Egyptian empire, the Lord settled His people in the midst of the Assyrian, Babylonian, and other Near Eastern empires, whose masters intended to deprive of self-rule as many peoples—nations—as they could conquer.

* * *

Hazony rightly reminds us that “all states are perpetually on the verge of losing their cohesion and independence.” The Hebrew Bible first taught the fragility of political order, “at every moment either rising or falling, moving toward either consolidation or dissolution,” depending on “whether human freedom is aided or hindered by the state, and whether the extension of the imperial state [leads or not] to mankind’s enslavement.” Peoples who are free to rule themselves are perpetually at risk of giving up the conditions of nationhood—the moral minimum and independence—and hence of being absorbed into empires, as the Israelites eventually became the successive vassals of the Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans.

Empire also results from the mistaken faith that only an authority superior to discrete peoples can prevent their pursuit of disparate purposes from ruining peace and prosperity. Hazony may be excused for attributing the Western world’s taste for empire to Catholic Christianity. But regarding the Holy Roman Empire as a continuation of Roman imperialism, as he does, misconstrues Christian political thought.

In fact, Pope Gelasius I’s doctrine of “the two swords,” secular and spiritual, restating as it does Augustine’s City of God, simply reiterates Christ’s distinction between duties to Caesar and duties to God. Hazony himself notes the same distinction, and tension, between the demands of what he calls the “right of national self-determination” (secular power) and those of the “moral minimum.” What’s more, the medieval political order was anything but imperial: countless jurisdictions flexed manifold autonomies. The emperor was one German potentate among many.

Hazony credits the Protestant Reformation for having introduced diversity in Christendom. But in fact, for good and ill, it only confirmed its constituent parts’ growing independence. Hazony cites Sir John Fortescue’s De Laudibus Legum Angliae (In Praise of the Laws of England, circa 1470) as an example of the new diversity. But Fortescue was describing laws and customs elaborated during the Middle Ages, while kingdoms in Spain and Christian republics in Italy were doing the same. Throughout Europe, post-Reformation politics became much harsher as rulers, Protestant as well as Catholic, arrogated to themselves spiritual as well as temporal powers—for which they were roundly criticized by both Catholic cardinal Roberto Bellarmino and Protestant divine Richard Hooker.

* * *

America’s founding generation was both steeped in the Bible and confirmed by circumstance and habit to decide things for themselves. They rebelled in the name of a politics such as Fortescue had described, arising from a version of Christian politics that, by then, was a distant memory. Having come a long way to get clear from the rest of the world, the colonists were keen to keep clear—and assumed that they could stay clear because the world is rightly made up of independent nations. Conscious as they were that their county’s future greatness would tempt their progeny to follow Rome’s path, they eschewed the Pax Romana explicitly. Nevertheless, any number of Americans today, including conservatives, yearn to administer a Pax Americana.

But in America, where imperialism is a curse word, advocacy of such things as the European Union, Hazony points out, “is conducted in a murky newspeak riddled with euphemisms such as ‘new world order,’ ‘ever-closer union,’ ‘openness,’ ‘globalization,’ ‘global governance,’ ‘pooled sovereignty,’ ‘rules-based order,’ ‘universal jurisdiction,’ ‘international community,’ ‘liberal internationalism,’ ‘transnationalism,’ ‘American leadership,’…and so on.”

He strives to show how modern liberalism subverts any people’s capacity for nationhood and readies them to become imperial subjects. Citizens need “the minimum requirements for a life of personal freedom and dignity for all,” which, in turn comes from observing the Ten Commandments or something close. This provides the strength and coherence (wisdom, too?) for securing “political independence…a right of self-determination…the right to govern themselves under their own national constitutions and churches without interference from foreign powers.” “Yet these two principles,” he observes,

also stand in tension with each other…. [N]atural standards of legitimacy…[mean] that nations cannot do rightly whatever they please…. On the other hand the principle of national freedom strengthens and protects the unique institutions, traditions, laws.

This tension “imparted a unique dynamism to the nations of Europe”—and, one might add, to the United States.

This beneficent nationhood is being undone from within by what Hazony calls the “liberal construction,” namely, the assumption that “there is only one principle at the base of legitimate political order: individual freedom.” Its root, he argues, is John Locke’s contention in his Second Treatise that “consent” is the only bond between human beings. “[T]he individual becomes a member of a human collective only because he has agreed to it, and has obligations to that collective only if he has accepted them.” That individual is motivated, argues Harzony, only to achieve and preserve a secure and pleasant life. “Anyone embracing [such premises] would be unable to understand, much less defend, the existence of the family…. [I]n real life, nations are communities bound together by mutual bonds of loyalty, carrying forward particular traditions…common historical memories, language and texts, rites and boundaries…identification with their forefathers and a concern for what will be the fate of future generations.”

* * *

Like Notre Dame’s Patrick J. Deneen, Hazony sees modern progressivism as the culmination rather than the repudiation of the founders’ liberalism. Thus, America was corrupt from the start. Yet, an elementary acquaintance with the founders’ writings should be enough to show that they did not read Locke in the way Hazony and Deneen do. Consider John Quincy Adams’s description, in his 1821 Fourth of July speech, of the Americans who declared independence:

[T]he people of the North American union, and of its constituent states, were associated bodies of civilized men and Christians, in a state of nature…bound by the laws of God, which they all, and by the laws of the gospel, which they nearly all, acknowledged…by the principles which they themselves had proclaimed in the declaration…by all those tender and endearing sympathies, the absence of which, in the British government and nation, towards them, was the primary cause of the distressing conflict in which they had been precipitated…by all the beneficent laws and institutions, which their forefathers had brought with them from their mother country…by habits of hardy industry, by frugal and hospitable manners, by the general sentiments of social equality, by pure and virtuous morals; and lastly they were bound by the grappling-hooks of common suffering under the scourge of oppression…. Had there been among them no other law, they would have been a law unto themselves.

Any people that lacks adherence to laws natural and divine, reverence for their ancestral institutions, habits of frugality and industry, general sentiments of social equality, pure and virtuous morals, and a willingness to endure personal suffering for common causes—in short, who lack “bonds of mutual loyalty”—is a collection of individuals whose consent is always up for grabs. Such people cannot become, nor long endure as, a nation.

Nor can such people hope to find peace and justice under any supra-national arrangement. That is because the question “who rules?” hovers over all politics. The answer, which Plato and Aristotle never forgot and which Hazony reminds his readers, is: more often than not, rulers rule on their own behalf. Even imperial imposition of impartial norms is an illusion because, invariably, empires reflect the emperor’s character. As Hazony explains:

The empire…necessarily concerns itself with abstract categories…that are, in its eyes, “universal.” But these categories are always detached from the circumstances and interests, traditions and aspirations of the particular clan or tribe to which they are now to be applied. This means that from the perspective of the particular clan or tribe, imperial law will often appear to be ill-conceived, unjust, and perverse. Yet…the unique clan or tribe with no standing to protest…must inevitably strike the imperial order as narrow-minded.

More importantly, “the imperial state has to be built on some bond of mutual loyalty, or its solders will not be willing to fight and die for it.” This means that every empire depends on “a ruling nation, its language and customs, and its unique way of understanding the world.”

* * *

This discussion would have been more enlightening had Hazony descended from generalities to describe the empires that have ruled so much of mankind for so long, and then compared them with the “liberal empire” that attracts so many of today’s elites. The best such discussion is James Kurth’s “The Adolescent Empire” (National Interest, Summer 1997). Consistent with classical philosophy, Kurth cites particulars to show that every empire reflected and promoted a certain type of person and corresponding way of life. For the Spanish empire it was the priestly warrior, Ignatius of Loyola. The British empire was by, of, and for Harrow’s and Eton’s noble graduates. The brief post-World War II American empire was about Dwight Eisenhower, George Marshall, and Dean Acheson—intensely practical adults. Kurth then asks what human type his contemporary America honored, what way of life did it promote? Youthful entertainers like Michael Jackson and Michael Jordan, he regrets to say.

Since then, a very different kind of person has set the tone of life in America and the rest of the Western world. In our time, adults imitate and children aspire to become wealthy, well-connected CEOs, such as Tesla’s Elon Musk and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, or one of the bankers or high-ranking officials who join them for the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting every January in Davos, Switzerland, for conspicuous consumption, collusion, and self-congratulation. And in fact, during the past quarter-century, Newspeak terms like “multilateralism,” “new world order,” “globalization,” “pooled sovereignty,” and “rules-based order” have meant neither more nor less than more power and wealth for “Davos Man.” Hence, in practice, Hazony’s choice between “nationalism” and “imperialism” asks whether Europeans and Americans will succeed in clawing back the power—domestic and international—they have ceded to Davos Man’s empire.

* * *

Unfortunately, readers must wait a hundred pages before the book’s key term is defined. A “nation,” Hazony writes, is:

a number of tribes with a shared heritage, usually including a common language or religious traditions, and a past history of joining together against common enemies—characteristics that permit tribes so united to understand themselves as a community distinct from other such communities that are their neighbors.

There is nothing here either about independence or morality, though Hazony adds both two pages later without connecting them to the original definition. He also considers India a nation, though it has none of the main definition’s qualities, never mind a moral minimum.

The author’s explanation for European nationalism’s violent history may be the book’s weakest point. Although the leaders may be “sometimes misguided,” he writes, “wars between national states tend to be relatively limited in their aims, in the resources invested in them, and in the scale of the destruction and misery they cause.” Nevertheless, Europe has “known general wars of virtually unlimited devastation” because, Hazony asserts, these were not really national wars but ideological wars “in the name of some universal doctrine.” This includes the Second World War, “in which a German-Nazi empire aimed at establishing a new order according to its own perverse universal theory.” That is a plausible explanation, but weak. Most of the Second World War’s fighters—Germans and Russians, too—fought for their nation rather than for Nazism or Communism or democracy.

* * *

World War I is Hazony’s pons asinorum. Like Lenin in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, he attributes the European powers’ drift to war to their struggles for overseas empire. The Great War’s combatants were “world states,” not national states, he argues. Alas, not so. In fact they had become what one might call “idol states,” objects of cult, ritual, and human sacrifice. The process had begun in the late 15th century. As kings gained ascendancy over the Church, they focused even more popular sentiment onto themselves.

As the French Revolution finished severing government’s legitimacy from Christianity, it wrapped government—especially its military side—in pseudo-religious ritual, complete with national anthems, the most explicit of which was “Deutschland Über Alles,” or Germany Over All, which replaced officially what had been Prussia’s unofficial anthem, “Nun Dank Wir Aller Gott,” Now Thank We All Our God. Nineteenth-century European literature presents each nation as a self-contained “race,” with its own “genius,” and that devotion to the nation was indeed “über alles.” Nothing stood in that pseudo-religious devotion’s way. Socialists were sure that since the workers had no fatherland, they would not fight each other. But did they ever! And the Christian churches, instead of pointing out that the Great War’s disproportion between harm inflicted and goods sought was the very definition of unjust war, abetted its slaughter. The nationalism of that era died a bloody death, between 1914 and 1918, for better and for worse.

But that nationalism is not today’s problem. We suffer instead from the insidious growth of an imperialism that seeks to expand its global reach while feeding on the last of its decomposing remains. Because Yoram Hazony’s The Virtue of Nationalism states the essence of today’s problem so clearly, we may cheerfully overlook its shortcomings.