Books Reviewed

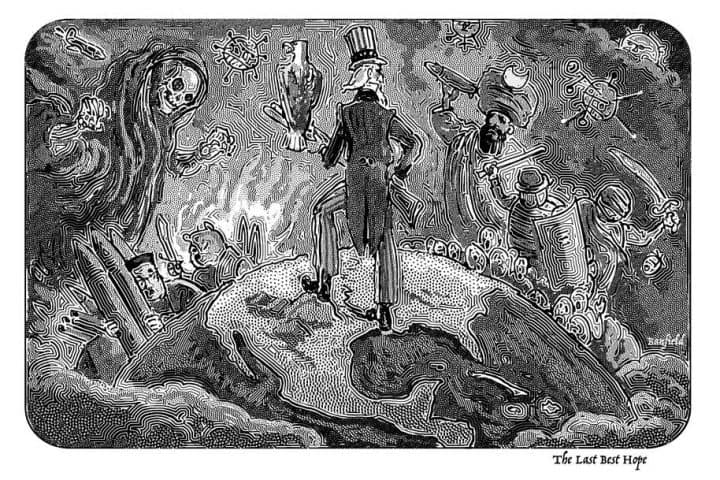

Our progressive march toward a harmonious, borderless world, with universally accepted rules governing everything from commerce to human rights, appears to have stalled. Though globalization’s devotees continue their annual political pilgrimage to Davos, most political leaders appear more interested in protecting their citizens or ensuring their regime’s survival than in solving “global challenges.” Global citizenship’s promise and the exalted values of diversity and inclusivity, moreover, don’t seem to appeal to the masses. People are preoccupied with the fate of their own cities, neighborhoods, families, friends, and—yes—nations. The quest to create global citizens who fervently face the day’s global challenges—from sweating polar bears to plastic swirling in the oceans—leaves them cold.

The most common response to such indifference is condemnation. Before being elected president, Barack Obama bitterly complained about people clinging to their “guns or religion.” Hillary Clinton similarly derided the “deplorables” who wouldn’t accept the progressive agenda. Donald Trump’s 2016 electoral victory and analogous developments in Europe have drawn denunciations on both sides of the Atlantic. Learned critics fear the world is regressing to a condition where states have borders, mass migration is controlled, and nations protect their heritage. Instead of postmodern globalization, we seem to be relapsing into the pre-modern age of nationalism and tribalism. War, they think, is surely to follow.

* * *

In her new book, Political Tribes, Yale professor Amy Chua tells the worried Davos man to calm down. Chua—whose first book, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother (2011), became a New York Times bestseller for four months—explains that the desire to belong to a group—a tribe—is neither unique to pre-modern man nor a modern redneck psychosis, but simply part of our human nature. In the book’s first words Chua states a truth most of us know, though it bears repeating:

Humans are tribal. We need to belong to groups. We crave bonds and attachments, which is why we love clubs, teams, fraternities, family.

This need to belong demarcates our tribe from others: the “tribal instinct is not just an instinct to belong. It is also an instinct to exclude.” We love our kids, not just kids in general; we crave these friends, not friendship in the abstract.

Left, Right, center, progressive or conservative, nationalist or globalist—we are all tribal. Many reject that claim, believing they’ve achieved a higher level of civilization. “American elites,” Chua observes, “often like to think of themselves as the exact opposite of tribal, as ‘citizens of the world’ who celebrate universal humanity and embrace global, cosmopolitan values.” That’s plain silly, of course; they simply belong to a cosmopolitan tribe as judgmental and exclusive as any other. Chua’s strong introduction refreshingly describes groups across the ideological spectrum as just that—groups—which necessarily exclude outsiders.

* * *

Unfortunately, after this promising beginning, her book meanders, becoming multiple books compressed into one lengthy pamphlet on the United States’s ills. Five of her eight chapters recount how Americans, in particular, fail to understand tribes. We become involved in wars without understanding the motivations of the parties we support or oppose. As a result our foreign policy generates one disaster after another. Chua begins with the Vietnam War, in which U.S. policymakers misdiagnosed Vietnamese motivations, ignoring the anti-Chinese sentiments of the majority of the local population. The reader is next transported to Afghanistan where, since the Soviet invasion, we’ve ignored the intricate tribal divisions between Pashtuns and other ethnicities. Iraq presents another example of our failure to understand tribes—though a brilliant officer, H.R. McMaster, got his soldiers to develop in-depth knowledge of Iraqi tribal configurations, so there’s hope. But the problem was (and is) much bigger, and a few brave individuals could only address the symptoms rather than the deep causes. As she notes, the prevailing belief is that “markets and democracy would transform the world into a community of prosperous, peace-loving nations, and individuals into civic-minded citizens and consumers.” Instead, we find tribes killing each other, and enjoying it.

Chua next examines Islamist tribalism, showing how group mentality can lead to acts of unspeakable brutality. She warns that ISIS and similar terror groups will continue to form so long as Muslims feel victimized throughout the world. A chapter on Venezuela—another country we don’t understand—follows. Hugo Chavez’s rise was surprising only to those who did not comprehend the deep cleavages in Venezuelan society, driven by skin color (Latin American societies are, we’re told, “pigmentocratic,” favoring those with lighter skin color) and wealth inequality.

Chua’s dizzying survey ends with Trump and the United States, moving from “Nascar nation” to “Occupy Wall Street,” from MS-13 to the more than 50 Facebook designations of gender. Her overarching point is that the United States, torn by tribalism, no longer acts as a “super-group” in which tribes coexist. Undoubtedly, there is something to this: the continued postmodern insistence on identity as the self-realization of individual preference is indeed splintering society.

* * *

Unfortunately, in trying to explain everything, from the Vietnam War to President Trump’s appeal, Political Tribes loses its analytical value. At the heart of this problem is its bloated concept of tribes, encompassing family and friends, churches and Berkeley activists, ethnic and racial groups, social classes and sports fans—the list goes on. When “antifa” and the family are both “tribes,” equal in their effects on society, the concept becomes of questionable utility. Not every woman is my wife and not every kid is my kid—and I won’t pay for college for anyone but my kids. We naturally prefer our own. But this preference does not make me a racist or a hater of other groups.

Not all tribes are created equal. Some are necessary for a well-ordered polity; others, destructive of it. The whims of utterly confused, gender-bending millennials are not comparable to a family that works hard at passing traditions and culture to the next generation. The problem is not with “tribes,” but with some of them. The difficult, divisive question is: which tribes are the problem?

Given the impossibility of answering this question without taking a clear stand, Chua is left with only a vague hope that the U.S. will transcend its current tribal fights. But it remains unclear how this will occur: Chua senses only a “shift.” For instance, we are moving past our tribal differences over same-sex marriage, she claims; and the all-minority cast portraying the Founding Fathers in Hamilton indicates for her a similar transcendence of race. Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Lin-Manuel Miranda are among her heroes. If “we’re to come together as a nation,” Chua declares, “we all need to elevate ourselves.”

But is accepting a drastic redefinition of marriage or rewriting history really a sign of a return to a more united and ordered community? The divide in the U.S. and the West largely arises from our inability to agree on the fundamental issues of justice and the good life—not just on proper levels of taxation or the scope of foreign military involvements. If to “elevate ourselves” means accepting the existence of an objective reality, a higher law to which our laws ought to be “brothers” (as Socrates says in Plato’s Crito), then there’s hope. Unfortunately, Amy Chua’s assumptions prevent her from seeing it.