In the wake of the presidential election half of our divided nation asked, incredulously: how did Donald Trump lose? Equally incredulously, the other half asked: how could he have almost won?

Joe Biden’s victory will not change the Democratic and Republican parties’ basic dilemmas. For Democrats, the “fundamental transformation” of America promised by Barack Obama is still far from electorally secure. For their part, Republicans haven’t found a way to appeal to a majority of voters—even had Trump won the Electoral College, no fraud claims could have erased Biden’s 7 million national-vote lead.

Why Trump Lost

Granted, the election polls’ repeated underestimating of the Trump vote suggests the possibility of “shy Trump voters.” It’s also possible (though not certain) that job approval polls similarly underestimated Trump’s support throughout his presidency. But it is important not to exaggerate the significance of this effect. Real Clear Politics election polling averaged a Biden lead of 7.2% on Election Day. The end result was a national Biden lead of 4.5%. If one incorporates a similar effect to Trump’s approval ratings from the beginning of his presidency through election day he would still be the most consistently unpopular president since polling began. Most presidents have experienced lows; many have been in the low 40s a year before being re-elected. No one has spent their entire presidency there.Trump’s defeat should not have surprised anyone. It is a truism of presidential elections that, when an incumbent runs for re-election, the election is largely a referendum on the incumbent. This incumbent was the most consistently unpopular president since polling began. According to presidential job approval surveys, fewer than 40% of Americans approved of Trump’s performance for most of his first year in office, and fewer than 45% for most of the remainder of his presidency. The Real Clear Politics approval average showed him reaching a high of 47% after rallying the country to confront COVID-19 in late March 2020, before falling again. His approval ratings were “underwater”—the number approving outnumbered by the number disapproving—from January 27, 2017 for the remainder of his presidency.

The remarkable stability of Trump’s (low) approval ratings was matched by a remarkable stability in Biden’s lead over Trump since mid-2019 when pollsters began regularly asking questions about head-to-head matchups. Biden led by about five percentage points for over a year until building an even larger lead in early October. Some of that lead at the end of the race was clearly dubious, and may have been before. But, again, probably not enough to erase it.

Then there were the circumstances in the country, which resembled other times incumbents were defeated. Historically, it is difficult to beat an elected incumbent—it usually requires a conflation of difficulties that produce not just hardship but a sense of national unravelling. The last losing incumbent was George H.W. Bush, who in 1992 faced a recession, the Rodney King riots, and a mostly positive—but fatal to Bush—sense that the world had changed in ways that required adjustment. Before Bush the last losing incumbent was Jimmy Carter, who in 1980 faced recession, inflation, high interest rates, riots in Miami, oil shortages, and simultaneous foreign crises, including the humiliating hostage crisis in Iran. Before Carter there was Herbert Hoover, who had to contend with the Great Depression, increasingly severe social unravelling, and the disorder surrounding the Bonus Army. (Gerald Ford, who came between Hoover and Carter, was not a comparable case, having not been elected to the presidency initially, but he also faced his share of outsized difficulties, most notably the backlash to Watergate.)

Trump faced COVID, a deadly crisis of international scope that almost no democracy handled well, a depression-like economic plunge associated with the virus and the draconian lockdowns, and the most widespread and destructive civil disorder since the 1960s. Near election day, the percentage of Americans who said the country was on the wrong track outnumbered those who thought it was on the right track by 61% to 32%. That actually represented a modest recovery since August 3, when the margin was 71% to 23%. Except for a moment in March (and perhaps late August) Trump was never able to turn the crises to his advantage. Instead, his reality-TV persona and endless Twitter bombardment proved unequal to the tasks at hand—to calm the nation, embrace the presidential role of head of state, administer the executive branch competently, and make a careful, reasoned argument in his defense.

In the end, too many Americans simply stopped listening. Many had stopped listening before 2020 began. Part of the referendum on Trump didn’t have to do with partisan issues or the state of the country, but with his conduct as president. Though his most fervent supporters tended to dismiss the importance of his comportment, it is undeniable that voters had some vague “presidential” standard which Trump too often failed to meet. CNN exit polls showed he narrowly won among the three fourths of voters who said issues were most important; Biden held a 2-1 margin among the quarter of voters who said the candidates’ personal qualities were most important. Fifty-four percent thought Biden had the temperament to be president; only 44% said Trump did. The president’s boorish behavior in the first debate did not help—it was followed immediately by a doubling of Biden’s lead in public election polls (though it is hard to untangle the effects of the debate from news of the president’s contraction of COVID days later).

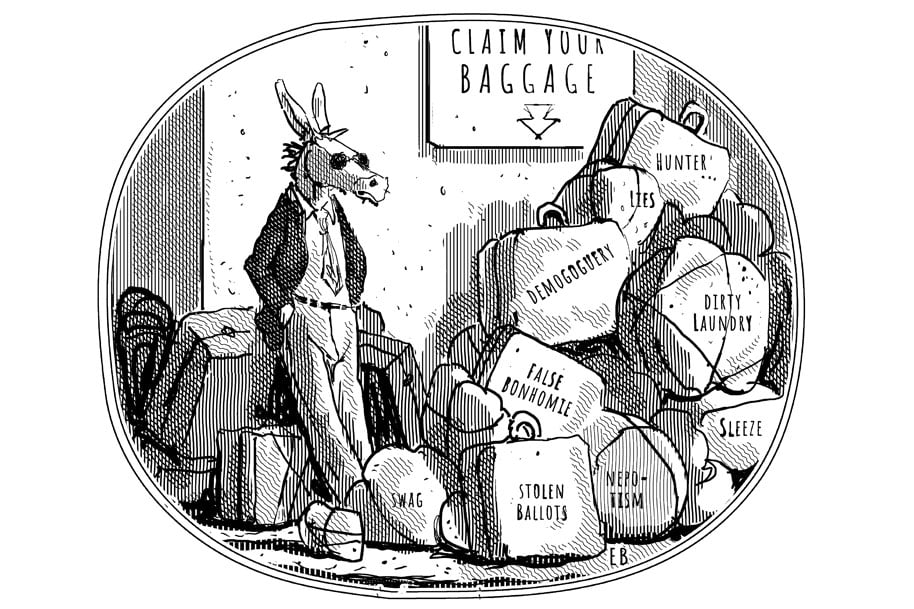

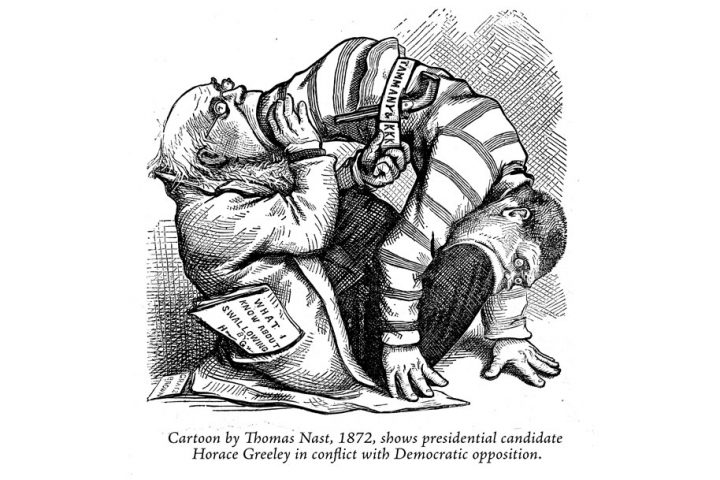

Trump’s defenders argue that Biden’s support owed no small amount to the bias of an overwhelming majority of the national news media, which consistently painted the president in the worst light and his challenger in the best light. They have a point. Since at least 2004, when CBS News tried to peddle an obvious forgery as part of its war on George W. Bush, we have seen a kind of return of the partisan press of the 1800s. In the 1800s, however, there were Democratic and Republican newspapers in every large town and city. Today finds almost all major newspapers, all major networks but one, and all social media empires serving as Democratic Party adjuncts. The result, starting with two and a half years of Russia collusion coverage for which no one has yet apologized, was the most unbalanced coverage of a president in modern times.

Coverage did not improve during the campaign. Coronavirus stories focused on the alleged failings of Trump and Republican governors while letting Democrat Andrew Cuomo, for example, off the hook, despite New York’s suffering a death rate more than twice Florida’s. The Atlantic claimed Trump insulted dead American servicemen, though the story was unsourced and the claim disputed by people who were there (some of whom—like John Bolton—had fallen out with Trump and had no reason to defend him). Bob Woodward revealed Trump had kept worrisome assessments of COVID from Americans early on to avoid panicking them. The New York Times published a piece on Trump’s taxes, which were almost certainly provided illegally.

Worse was what wasn’t covered. The story of Hunter Biden’s laptop, which would undoubtedly have dominated the news for weeks had the laptop been Donald Trump, Jr.’s, was aggressively spiked by social media and most of the rest of the national media complex. A post-election Media Research Center survey showed that, in crucial states, nearly half of Biden voters had never heard about Hunter’s laptop. Around 5% of his voters said they would have switched their votes had they known. The president’s momentous diplomatic victories in the Middle East? The big comeback in GDP in the third quarter? Kamala Harris’s Senate voting record, putting her to the left of Bernie Sanders? All sent down the memory hole after at most perfunctory acknowledgment. One is tempted to say that either we will start having a two-party press or we will stop having a two-party country.

But it is too easy to blame the media. Trump did, after all, give them plenty of material to work with. What fit of arrogance persuaded him to give unfettered access to Bob Woodward? Besides, a large part of the public had already given up on the prospect of evenhanded coverage from the national media—and adjusted their thoughts accordingly. And when Trump had the opportunity to connect with Americans unfiltered by the media—tweets, debates—he often looked no better than when the media controlled the narrative.

What about the impact of mail-in voting? Leaving aside the potential for fraud, there were two unquestionable effects. The first was to boost voter turnout, probably disproportionately on the Democratic side—both because Democrats were, on average, more afraid of in-person voting this year and because Democrats rely more heavily on a support base (starting with young voters) that is more likely to vote if one puts a ballot directly in their hands. The second effect was more random and may have either reinforced or undercut the pro-Democratic effect. When all is said and done, a non-trivial number of ballots will have gone missing, either on their way to or from voters. How those random misfires affected vote totals may be unwound someday with considerable difficulty; it is unknown today.

Coronavirus may thus be said to have hurt Trump in three ways: by darkening the national mood, by throwing the nation into a recession, and by expanding a voting system that (probably) advantaged Democrats. But, remember, the voting system had the effect of confirming what the job approval data and head-to-head polls had been saying all along.

In the end, Trump lost the crucial suburban and Independent vote, after narrowly winning both in 2016. Indeed, with a few exceptions, his vote share deteriorated across the board, in nearly every group—men and women, Catholics and evangelicals, rural as well as suburban, college-educated and those without degrees, even military veterans, where his advantage fell from 26 percentage points in 2016 to 10 in 2020. Given the realities under which the election was taking place, any incumbent would have faced an uphill climb. Of eight notable election models fashioned by political scientists and historians, most based on the “fundamentals” of the election, six predicted a Biden win.

Why Trump Almost Won

While half the country wonders what went wrong in Trump’s defeat, the other half wonders what went wrong in Biden’s victory—why wasn’t it a blowout? Why did they go to bed fearing they had lost, then sweat for days waiting to find out if Biden’s small, early-morning margins in key states would hold up?

First, the steep economic decline related to COVID was sandwiched between a strong Trump economy beforehand and a sharp recovery after midyear. Economic performance was Trump’s best area in polls throughout his presidency, and remained so in the fall. A month before election day, Gallup released a survey indicating that 55% of Americans judged themselves better off than they had been four years before. American elections are always about more than economics, but this data point alone should have forced pollsters and pundits to re-examine their confident predictions of a Biden blowout. The economy was important but in conflicting ways for different people—and sometimes for the same people.

Gallup collected additional survey information that telegraphed to careful observers that no blowout was to be expected. In June, Democrats held a 33 to 26% lead over Republicans in self-reported party affiliation; by October, Republicans had drawn even, 31% to 31%. Counting “leaners,” Democrats led by a 50% to 39% margin in June—an advantage whittled down to 49% to 45% by October.

The narrowing of the partisan gap since summer was undoubtedly the result of the Democratic Party’s increasing radicalism, manifested most clearly in their embrace of Black Lives Matter—despite its Marxist roots and connection to riots around the country—and their refusal to acknowledge even the existence of Antifa during the latter’s nightly assaults on a federal courthouse in Portland. BLM and Antifa were openly revolutionary. One BLM leader in New York promised that if the group’s demands were not met, “[W]e will burn down this system…. And I could be speaking figuratively. I could be speaking literally.” Another in Chicago defended rampant looting as a form of reparations. With virtually no criticism by any prominent Democrat, rioters tore down or defaced statues of, among others, George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, a Wisconsin abolitionist who died in battle at Gettysburg, and the 54th Massachusetts regiment—the second unit of black troops in the Union Army. Add to this picture calls by prominent Democrats to “defund the police,” end fossil fuels, pack the Supreme Court, enact large tax increases, and reform health care in a way that might ultimately destroy private insurance, and the implicit subtext of the Democratic campaign was operating at cross-purposes with Biden’s explicit attempt to deliver a Warren Harding-esque “return to normalcy.” Normalcy, the Green New Deal, riots, CHAZ—one of these things is not like the others.

Just as Trump gave Democrats plenty of ammunition to run a campaign against his character and temperament, Democrats gave Trump abundant material to turn his re-election into an existential fight for America. It didn’t prove enough to overcome the referendum dynamic and win, but it was enough to narrow the gap. And it was enough to give Republicans a chance to turn the tide in the congressional elections, where they held Senate losses well below expectations—at least until they blew the Georgia runoffs two months later with a strong assist from Trump himself—and actually gained seats in the House, putting them within striking distance of a majority in 2022.

There are at least three interesting positive observations one can make about Trump’s vote. The first, frequently heard post-election, is that his smaller share of the white vote compared to 2016—predominantly among college-educated suburbanites—was partially offset by a larger share of the non-white vote. Trump gained four percentage points among blacks (to 12%), four among Latinos (to 32%), and seven among Asians (to 34%). Republicans might learn that they can hold to a firm anti-wokeness line and still increase support among non-whites by aggressively campaigning for their votes. The most woke people in America, after all, are affluent whites—not blacks, Latinos, or Asians.

The other two observations have been largely lost in post-election commentary. One is that, according to exit polls, Trump won among voters who decided in October whom to support. Hunter Biden broke through to some voters despite the best efforts of the national media and Twitter’s Jack Dorsey. So too did Biden’s admission in the second debate that he intended to end fossil fuels in America.

The third positive observation is that Trump broke even among those who had voted before. Biden’s entire popular vote margin was accounted for by first-time voters.

Both observations repeated results from 2016. Trump won October despite the late-breaking Access Hollywood tape; he also lost first-time voters but broke even among all others.

With all the focus of political scientists on the race’s fundamentals, it is easy to forget that campaigns and candidates can matter, at least at the margins. President Trump was an exceptionally polarizing figure who mobilized a record number of voters both for and against. Biden won by playing it safe, remaining in his basement for extended periods and frequently declaring an early “lid” on his campaigning. Biden’s strategy seemed to have been inspired by Napoleon, who was reported to have remarked that one should never interfere with the enemy when he is in the process of destroying himself. It is also altogether possible that Biden was not capable of greater exertion.

But whether due to Napoleonic brilliance or physical and mental exhaustion, Biden’s passivity gave Trump the opportunity to make the election close by mobilizing his enthusiastic supporters. In 1948, “President” Tom Dewey found out the hard way that Americans like a scrappy candidate and are reluctant to vote for those who take victory for granted. Biden nearly learned the same lesson. Trump was a live candidate, running a real campaign. Biden was a cardboard cutout who ventured forth so intermittently that it was not an unreasonable question at several junctures whether he was still alive. When he did appear, he steadfastly refused to say anything (except by accident) that would clarify the deliberately muddy picture his campaign had created. Would he condemn violence by BLM and Antifa? I condemn violence. Those white supremacists are nasty. Would he pack the Supreme Court? You’ll find out after the election. In any case, voters don’t deserve to know. It is hardly surprising that a certain subset of voters rebelled, choosing the lively candidate with views that were easy to parse.

Not least, Trump nearly came away with a win because of the ongoing advantages reaped by the Republicans from the more efficient distribution of their support within the Electoral College system. Unlike Hillary Clinton in 2016, Joe Biden did not owe his entire popular vote lead and then some to California. Nevertheless, three fourths of his 7 million vote national lead came from the Golden State. Democrats’ refusal to move to the center in either their issue positions or their vice-presidential choice meant that states such as Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Georgia, Arizona, and Nevada would be hotly contested. Democrats gambled that Biden could rebuild the old “Blue Wall” by simply reaping the benefits of Trump’s weaknesses, and it worked. But only barely. Most of the crucial states that flipped were states Trump had won by the skin of his teeth four years before. In 2020 Biden won them the same way.

The Issue of Fraud

Of course, no discussion of 2020 would be complete without an assessment of the allegations of massive fraud made—increasingly intemperately—by the president from the early hours of November 4 on. Two things should be stipulated. One is that fraud does occur in the United States; happy assurances to the contrary are factually wrong, starting with a congressional election in North Carolina as recently as 2018 that was vacated and re-run due to widespread fraud. The other is that Democrats demonstrated over the last four years a willingness to bypass any and all ethical constraints to take down President Trump.

Having said that, one has to make distinctions between the varying types of irregularities alleged. The Trump camp, for example, alleged that in many key states there were a large number of votes cast by, or under, the names of ineligible voters. Except for one legal case that is still ongoing in Georgia at this writing, such claims did not hold up in court. Evidence was often shaky, and judges naturally shied away from the draconian remedy of overturning a certified election. In other cases, Trump made the argument that procedures adopted in some states and metropolitan areas established the conditions for fraud, but that is not the same as proving fraud occurred.

The most dramatic claim was that industrial-scale fraud took place across multiple states, implicating both local election officials and the Dominion voting system. Indeed, since he needed to flip at least three states, such an expansive claim was necessary to keep Trump’s hopes alive. His supporters brought forth a variety of circumstantial arguments for the claim, but no indisputable hard evidence. Much of the circumstantial evidence was unpersuasive, based on Trump’s wins in the bellwether states of Ohio and Florida (bellwethers are, after all, bellwethers just until they aren’t) or on Joe Biden’s lack of congressional coattails (in 1988, 1992, 2000, and 2016, presidential winners also lost House seats) or on statistical rules that were of limited relevance to elections (Benford’s Law). Some demanded more consideration, including claims that certain spikes in vote reporting contained unreasonably large Biden majorities, but even then it wasn’t clear that the analysts knew what they were doing, and their numbers were often disputed by other analysts. The Trump legal team itself frequently backtracked on its claims and retracted allegations after making them.

On the other hand, a different form of circumstantial evidence strongly pointed toward a lack of widespread fraud. One would expect that if Joe Biden benefited from large-scale fraud, his reported vote percentages would be significantly higher than his showing in exit polls in the same state. However, Biden’s exit poll percentages in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin were almost identical to his reported vote count. And, while there has been considerable speculation about Dominion on both sides of the aisle over the years, the one actual case in which votes seemed to be switched—Antrim County, Michigan—did not prove what Trump’s supporters contended. In fact, an error in vote reporting—not vote counting—was caught and quickly corrected, and a hand audit of all Antrim County ballots verified the result in December. A hand recount of ballots in Georgia also confirmed the original result there.

In fact, the Trump campaign’s strongest argument had nothing to do with fraud but with the way numerous key states dramatically (and arguably unconstitutionally) altered their voting rules and procedures without consent of the legislature. (The Pennsylvania legislature also adopted an important change that seemed to violate its state constitution.) But these were legal battles that should have been fought months or years before election day. That the president and his team did not, by and large, fight them does not then constitute theft.

What Does It All Mean?

Political institutions are also closely divided. The presidency and Senate have reverted to Democrats, who also hold the House. But both Biden’s margin in the states that gave him the Electoral College and the division of parties in both houses of Congress are so close that no one can take anything for granted. In a 50-50 Senate, Joe Manchin, Susan Collins, and Lisa Murkowski are destined to become the Senate’s most pivotal members. State governments remain predominantly in Republican hands, and the federal courts are (for the time being) infused with conservatives. There is no consensus in the country, and our institutions reflect this. Although progressives made gains in 2020, they fell well short of what they had hoped, and Democrats could easily lose control of both House and Senate in 2022. For their part, though they need to assure ballot security, Republicans face risks from a continued focus on fraud, including further alienating suburban voters and accidentally triggering electoral reforms that lead in the direction of a federalization of elections. The historical significance of the election will be unclear for years. It has exposed challenges for both parties, including divisions within them. The battle between establishment Democrats and progressives is just beginning. The struggle between traditional Republicans and Trumpists, largely submerged for most of Trump’s presidency, has been revived by post-election voter fraud disputes and by the Capitol riot of January 6. In certain respects we now have four parties, not two. Things are likely to remain that way for some time.

Trump, being Trump, will want to remain in the game. He spoke for many Americans who felt betrayed and left behind, and he showed grassroots Republicans the fighting spirit they craved. His administration also accomplished a number of things that conservatives found praiseworthy, from constitutionalist judicial appointments to regulatory reform to a strong (though sometimes belated) stand against identity politics to formation of the anti-Iranian coalition in the Middle East.

Nevertheless, Trump failed to make himself acceptable to a majority, or even a plurality, of Americans. The cold fact remains that he was outpolled by 3 million votes by the most disliked Democratic nominee since polling began (Mrs. Clinton) and by 7 million votes by a mediocre career politician who barely campaigned and who will enter office older than Ronald Reagan was when he left. Even before he gave vent to his most narcissistic and demagogic impulses after November 3, there was simply no reason to believe Trump had the potential to expand his appeal enough to produce a different result. Now, his post-election meltdown threatens to become the dominant memory of his presidency, a descent that outweighs all else.

The foremost question for Republicans is whether they will be able to walk an electoral tightrope: apply what worked for Trump and keep his core constituency, while learning how to appeal to a broader electorate and avoiding the taint of January 6. The congressional elections of 2020 might be evidence that they have already started to construct such a political amalgam, and that voters are receptive to it. The next question is whether Donald Trump will let them.