Almost a century ago, President Woodrow Wilson addressed the Senate, offering his services as a disinterested peacemaker to the warring nations of Europe. With his assistance the Great War could be ended, he predicted, on the humane, negotiated basis of “peace without victory.” Two months later he led the United States into World War I and then into the negotiations that produced the debacle of the Treaty of Versailles, essentially winning victory without peace.

Liberals’ acumen on foreign policy has not improved since. To “peace without victory” they added a new objective, “war without victory,” which America pursued in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and now Syria. Ronald Reagan was actually the first president to set out to win the Cold War. And he did win it, thanks to a combination of good strategy and good fortune.

Barack Obama has said all along that his purpose was not to win but to end our wars in the Middle East. Yet even though his heart is not in them, he has extended the American military’s involvement in the Afghan fight and returned troops to the war in Iraq. But as with every liberal commander-in-chief before him, it is “the moral equivalent of war” that he finds compelling. He is quite prepared to conscript us all into wars on poverty, racism, disease, and other homegrown evils—wars without final victory, to be sure, but certain to keep the government growing, and all the more idealistic for it.

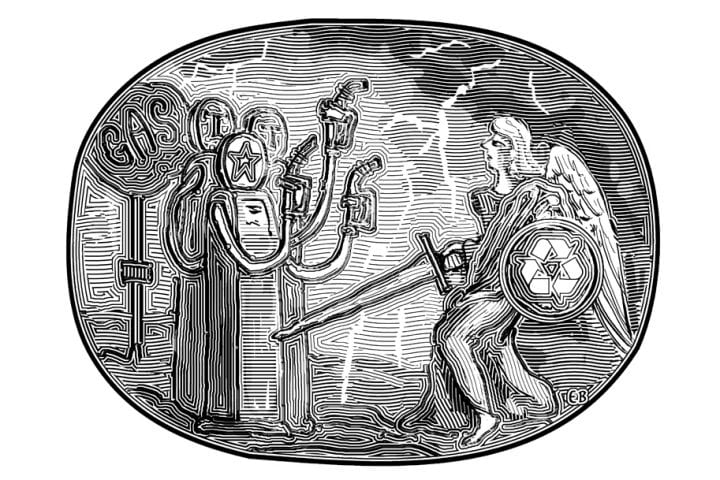

Obama didn’t repeat the mistake of George McGovern, who while running for president on the platform “Come home, America” said in an unguarded moment he would crawl to Hanoi on his knees if it would end the Vietnam War. Not only is President Obama prepared to use force abroad—particularly if it’s for misguided humanitarian purposes, as in the disastrous intervention in Libya—he is even prepared to enjoy using force abroad. He boasts of getting Osama bin Laden, and of hurling thunderbolts of death, Zeus-like, against individual terrorists within range of our drones. “When you come after Americans, we go after you,” he said to applause (but then, what isn’t said to applause?) in his recent State of the Union address.

“Let me tell you something,” he declared in the same speech.

The United States of America is the most powerful nation on Earth. Period. (Applause.) Period. It’s not even close. It’s not even close. (Applause.) It’s not even close. We spend more on our military than the next eight nations combined.

Worthy of one of the lesser Roman Emperors, Obama’s declamations are meant to counter “all the rhetoric you hear about our enemies getting stronger and America getting weaker.” But of course the two propositions are hardly incompatible. America is, currently, the most powerful nation on Earth. And America is growing weaker and our enemies stronger. China’s defense spending, for example, has for years been increasing at double-digit rates; ours has declined in recent years, increased at low single-digit rates before then, and always includes billions in wages and benefits. So long as these trends continue, at some point the two curves will cross. Besides, it isn’t all about dollars, technology, and firepower. Rome’s legions were usually more advanced in the art and science of war than her opponents were. But where is the empire now?

Left, right, and center, analysts of American foreign policy have noticed the accumulating mistakes of the Obama Administration. In Ukraine, the South China Sea, Syria, Iran, North Korea, and many other places, Obama has been wrongfooted—surprised by events and, even worse, by the kind of motives and conduct he thought history had abolished long ago. “In today’s world,” he told Congress, “we’re threatened less by evil empires and more by failing states,” but the terrorists who spring from these states, he assured his audience, cannot and “do not threaten our national existence.” Until they do. The threat that kept George W. Bush and Dick Cheney up at night—the fear of terrorists with nuclear weapons—has not disappeared just because no one wants to think about it.

Countries (and terrorist groups) that believe in winning their wars have a powerful advantage over countries that believe victory is optional, at best, and embarrassing and uncivilized, at worst. From the end of the Napoleonic Wars to August 1914, a general war in Europe appeared obsolete, impossible, contrary to all the interests of Europe’s great and civilized nations. But the long, fertile period of peace ended when the war to end all wars broke out. If conservatives have a single thought to offer on foreign affairs, it is this: there will be another war, and we had better win it, for the sake of a just and lasting peace.