Books Reviewed

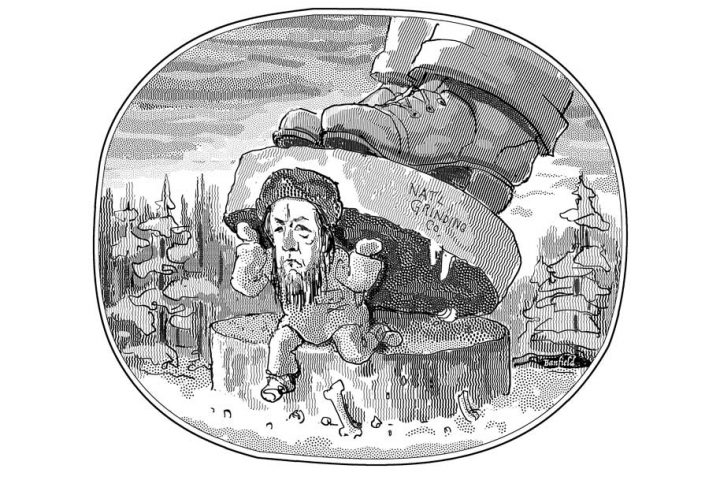

To slavery’s adversaries, 1857 might well have seemed the most dispiriting year in the most dispiriting decade in America’s short history. Earlier in the decade, with two infamous pieces of legislation—the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, followed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854—Congress had sustained slavery in states then existing and enabled its expansion into states yet to come. The crowning blow, delivered by the U.S. Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), removed the choice from Congress and made slavery’s expansion into federal territories virtually a constitutional mandate.

Friends of liberty faced a choice. They could either accept the Court’s ruling, condemn the entire political and constitutional order, and adopt a course of radical opposition; or they could reaffirm the anti-slavery Constitution, expose the Court’s errors in Dred Scott, and redouble their efforts to assemble an anti-slavery political majority on a sound constitutional basis. William Lloyd Garrison and his followers chose the former response. Constitutional abolitionists chose the latter, with Frederick Douglass even declaring after Dred Scott was handed down, “my hopes were never brighter than now.” Soon, he insisted, “the wisdom of the crafty [would be] confounded” and the high Court’s “scandalous and devilish perversion of the Constitution” would shock the nation into a rededication to its original principles. Even as slavery seemed politically invincible, an antislavery majority was forming, and it was doing so with solid constitutional support.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment vindicated Douglass’s confidence in abolition achieved by constitutional means and not by revolution, the opinion that the founders’ Constitution was pro-slavery persisted. Today, Garrison’s view of the original Constitution as a “pact with the devil” still finds support among a broad array of activists, public officials, and academic historians.

Against this doleful chorus comes Sean Wilentz, himself an impeccably credentialed historian at Princeton and the author of several books, including The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (2005), which won the Bancroft Prize and was a finalist for the Pulitzer. For Wilentz, the case for the Constitution as an anti-slavery document is “disarmingly simple.” Amid their compromises with slavery, the majority of framers refused, as James Madison reported in his notes from the Constitutional Convention, “to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.” In fact, nowhere in the Constitution do the terms “slave” or “slavery” ever appear. At every turn, those held in servitude are recognized by the supreme law of the land as “persons,” not property. It was this fundamental determination, Wilentz argues, that eventually “brought slavery to its knees.”

* * *

Slavery was a pervasive and largely uncontested presence in all British colonies from the 17th through the mid-18th century. In the North American colonies, slaves were numerous and slaveholders politically influential. But as more and more Americans during the Revolutionary era began to embrace the idea of equal rights rooted in human nature, a new, organized anti-slavery politics emerged. Although slaveholders north and south vigorously defended their institution, by the time the Constitutional Convention met in 1787, abolition measures throughout the colonies had already brought about the single largest emancipation of human persons to date.

That first wave of emancipation complicated the founders’ effort to establish their new republic. The anti-slavery momentum generated in the 1770s and ’80s frightened slaveholders, especially in the deep South, who escalated their demands for constitutional protections for their way of life. The same momentum led antislavery framers to believe they could safely make such compromises. They did so, however, within principled limits. As Wilentz shows in a careful reading of the Convention’s proceedings, in fashioning every major clause touching the subject, a majority of delegates firmly rejected slavery’s legitimacy.

* * *

In the notorious “three-fifths” clause in Article I, section 2—providing that three fifths of those enslaved (“other persons”) would be counted for purposes of taxation and electoral apportionment—critics from Garrison to the present have perceived a damningly corrupt concession to the pro-slavery interest. Wilentz rejects this view, reporting that the most vocal pro-slavery delegates, those from Georgia and South Carolina, “scarcely believed that the three-fifths clause offered slavery adequate protection.” For Wilentz, the decisive point is that by making persons rather than property the basis of representation, the clause “did not at all imply that the Constitution approved of or legitimized slavery.”

The same pattern appears in the framers’ heated deliberations over Article I, section 9’s clause concerning the slave trade. Whereas others have interpreted it as a slaveholders’ triumph because of its ban on export taxes and its 20-year protection of the Atlantic slave trade, Wilentz emphasizes that slavery’s defenders ultimately didn’t prevail in this contest. Even as they secured the opportunity to import thousands more enslaved Africans in the near term, they allowed a prospective federal power to limit slavery’s expansion—a power they had previously declared intolerable, and one that would prove vitally important to the anti-slavery cause in the decades to come.

Most telling of all is the framing of Article IV, section 2’s fugitive slave clause. In early proposals by South Carolina delegates Charles Pinckney and Pierce Butler, the clause would have required “fugitive slaves and servants to be delivered up like criminals” to “the person justly claiming their service or labor.” The reference to criminals was deleted after Pennsylvania’s James Wilson objected to the implied mandate that free states devote resources to fugitives’ recapture. The designation “fugitive slaves” became “persons bound to service or labor,” and the statement that slaveholders could claim such persons’ labor “justly” was likewise amended to “lawfully.”

* * *

The final version of Article IV, section 2 goes still further in undermining slavery’s legitimacy. After additional revision by the Committee of Style and Arrangement—a solidly anti-slavery committee, as Wilentz points out, that included no delegate from any state south of Virginia—the clause provides only that a fugitive’s labor “may be due” (emphasis added) on the basis of the laws of “one state” rather than the U.S. Constitution itself. What’s more, the fugitive is now described as a person “held,” rather than “bound,” to service—thus clarifying that slavery acted on its victims not by obligation but only by sheer force.

Subsequent chapters trace the career of anti-slavery constitutionalism through the ratification process, from ratification to the Missouri crisis, and finally from the Missouri Compromise to the outbreak of civil war. These chapters, informative in many particulars, serve generally to highlight the continuity of the main terms of controversy from the founding onward. As Wilentz shows, the pro-slavery debauching of the Southern mind long predated the labors of John C. Calhoun, even as disdain for the Constitution as a venal compromise with slavery preceded Garrison’s thundering editorials. Also present from the beginning were the non-extension and popular sovereignty arguments concerning the status of slavery in federal territories, which marked the primary point of contention in the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates. Through it all, the anti-slavery argument drew vital sustenance from the framers’ original careful drafting, and in the end, argues Wilentz, that “made all the difference.”

In the main, No Property in Man is a book to be welcomed by conservatives, in particular by constitutional originalists. It is strong as a work of historical scholarship. It would be stronger still, however, if the author had duly attended the efforts in recent decades by scholars of political philosophy and law, led by Harry V. Jaffa, to revive the natural-rights constitutionalism that informed the founders. Having neglected those efforts, Wilentz remains agnostic about which side in the slavery debate had the correct interpretation of the natural rights doctrine to which both appealed. On this crucial point he ventures no examination of any primary philosophic source; instead he offers only a tentative reference to “current research” by historian Holly Brewer indicating that John Locke’s ideas “were not nearly as friendly to slavery as has been generally assumed.”

* * *

A parallel shortcoming appears in constitutional interpretation. Rather than affirming, with Lincoln, that the founders’ Constitution is decisively anti-slavery and its compromises with slavery prudential, Wilentz holds that the framers “created a terrible paradox”—protecting and strengthening slavery, even as they delegitimized it and provided the basis for its eventual abolition. This is an equivocation, rooted in the author’s discomfort with constitutional originalism. Wilentz in fact performs an originalist inquiry, substantiating his conclusion that anti-slavery readings of the convention’s work “were more in line with what actually occurred in 1787 than others.” Yet, in virtually the same breath he says that neither the anti-slavery nor the pro-slavery interpretation “is ‘originalist.’” The Constitution, he asserts, is “a living document” whose meaning with regard to slavery emerged only in the political contentions of the post-founding decades.

What Wilentz seems to want is an originalism by another name, one somehow compatible with his progressive commitment to the living Constitution. He embraces the founders’ opposition to slavery, yet seems to dispense with the natural-rights constitutionalism that, according to the founders themselves, sustains that opposition. Complaining that originalism has been politicized, he endorses an approach that leaves politics, i.e., partisan political sentiment, as the only available source of constitutional meaning. In contrast to the original Progressives, he seems unwilling to accept the implication of this choice—that the founders’ Constitution must die in order that the living Constitution might live.

Even so, Wilentz’s conflicted aspiration to a progressive originalism is a positive development. A Left that is pro-Constitution and pro-American Founding would certainly be better than the Left we presently have. Frederick Douglass was more sensible than the Garrisonians, not only in constitutional interpretation but also in his prudential understanding that the abolition movement needed the Constitution and the American Founding in order to succeed. Unlike today’s social-justice warriors and identitarians, Sean Wilentz understands that the Left, too, needs the Constitution and the founding. That, at least, is progress.