Books Reviewed

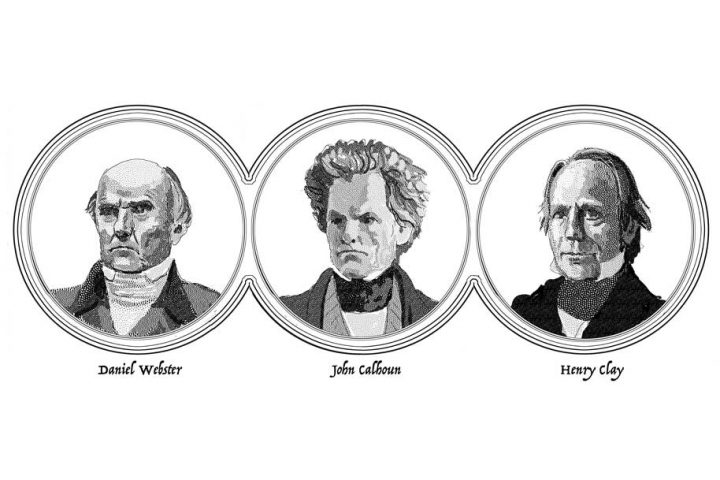

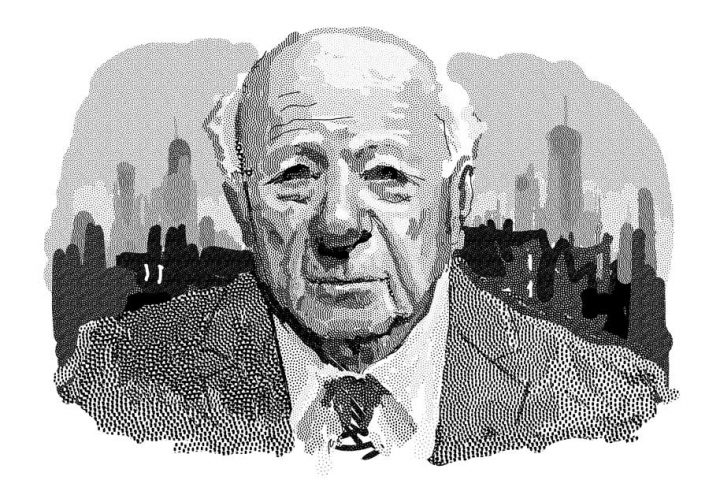

From the War of 1812 to the Compromise of 1850, American politics was dominated by four men: Andrew Jackson, the hero of New Orleans and two-term president; and three prominent senators: Henry Clay, John Calhoun, and Daniel Webster. Having previously explored this era in his 2006 biography, Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times, H.W. Brands now returns to tell the story of the “Great Triumvirate” in Heirs of the Founders: The Epic Rivalry of Henry Clay, John Calhoun, and Daniel Webster, the Second Generation of American Giants.

In a series of short, episodic chapters, Brands, the Jack S. Blanton Sr. Chair in History at the University of Texas at Austin, examines the intersection of personal ambition, party politics, and sectional division in a time of freewheeling democracy and Romantic passion. A gifted storyteller, he makes good use of his subjects’ oratorical prowess with generous, well-presented excerpts from their most important speeches, supplemented with the pithy observations of several contemporary diarists and other key primary sources of the period. The result is a lively narrative that reintroduces the senators and their political battles and goes some distance, at least, in establishing their claim to be “heirs of the founders.”

If Clay, Calhoun, and Webster were the founders’ heirs, what did they inherit? One obvious answer is the founders’ fame and prominence: they were political “giants”—and not just during their time in the Senate. Clay was the principal negotiator of three sectional compromises, Speaker of the House for ten years, secretary of state for John Quincy Adams, and the leader of the Whig Party for almost its entire history. Webster argued more cases before the Supreme Court than any other 19th-century lawyer, served as secretary of state first under William Harrison and John Tyler and later under Millard Fillmore, and attracted enormous crowds and a vast readership for his congressional and occasional speeches. Calhoun was vice president for both John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, secretary of war for James Monroe, secretary of state for Tyler, and the intellectual godfather of a Southern ideology that defended slavery as a “positive good” and the right of states to nullify federal laws and secede from the Union.

They were also heirs in another sense, according to Brands, as inheritors of the unresolved questions surrounding the proper balance of state and national power: “The founders had left deliberately vague where the boundary lay between state and national authority; similarly blurred was who would determine the boundary and how it would be enforced. They knew that any explicit answer might wreck their experiment in self-government before it got fairly started; they left their heirs to find a solution the country could live with.”

* * *

The search for such a “solution” was involved in all the most famous accomplishments of Clay, Calhoun, and Webster, though they couldn’t agree among themselves, much less establish a permanent consensus on the matter. For Clay, the answers were political, found in well-framed compromises that required neither side to give up essential principles. Prudence counseled mutual forbearance in examining the compromises too closely—the compromise itself was the thing, ennobled by the cause it served: the preservation of the Union as the foundation of American liberty.

Compromise, however, was inimical to Calhoun’s character and principles. “[W]e must meet the enemy on the frontier,” he said in a speech against accepting petitions calling for federal restrictions on slavery. His solution was philosophical, based upon necessary deductions from first principles. The several states, in their sovereign capacity, had made the national government. It was therefore their creature, not their master, and the states could rightfully judge the propriety of its actions—the states individually, since none of them had surrendered its sovereignty to the whole. Thus, for Calhoun, when a state believed the national government had assumed powers not delegated to it under the Constitution, it could nullify the law, declaring it unenforceable within the state. Such a judgment would stand unless the power was positively affirmed by a convention of the states and ultimately adopted in a constitutional amendment. In that case, the nullifying state could submit or withdraw from the Union if it could not accept the new terms of the federal compact.

* * *

According to Calhoun, not only was the logic of nullification airtight, but he also believed he had the greatest authorities on his side: Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, principal authors of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798, respectively, written in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts. Brands accepts Calhoun’s judgment here uncritically even though it was strenuously disputed by Madison himself at the time. In a private letter written in 1832, Madison explained that his Virginia Resolutions had consistently spoken of the “states” (plural) as the “parties to the Constitutional compact of the United States.” This “distinction was intentional” and, indeed, “required by the course of reasoning employed on the occasion”—a call for joint action. Though Madison admitted that the language of the Kentucky Resolutions was “less guarded,” Jefferson, in other writings, clearly denied essential premises of what Madison called the nullifiers’ “colossal heresy.”

Webster, unsurprisingly, attempted a legal resolution to these controversies. The people, not the states, had made the Constitution, he claimed in his famous reply to South Carolina Senator Robert Hayne (as Calhoun, vice president at the time, watched from the Senate president’s chair). In doing so, they had limited the sovereignty of the states in many particular ways, but most fundamentally in declaring the Constitution, laws made pursuant to it, and federal treaties the “supreme law of the land…anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.” Even state constitutions had to give way to federal authority when a genuine conflict existed. But who was to determine if such a conflict did exist? This too, Webster believed, the people had resolved beyond dispute by including cases that arise under the Constitution in the jurisdiction of the federal courts. “These two provisions cover the whole ground,” he concluded. “They are, in truth, the keystone of the arch! With these it is a government; without them it is a confederation.”

A federal power of judicial review necessarily followed from Webster’s constitutional premises. As Alexander Hamilton demonstrated in The Federalist, a judicial power to “pronounce legislative acts void, because contrary to the Constitution” follows from any combination of a sovereign people and a limited constitution: the courts must prefer the will of the people, as expressed in the fundamental law, to the will of their legislative agents, as expressed in mere statutory law. Brands, nevertheless, treats Marbury v. Madison (1803) as an unprecedented novelty, derived from Chief Justice John Marshall’s “dubious” reasoning. Brands further suggests that Marshall “strengthened the nation—as distinct from the separate states—in ways neither Hamilton nor Jefferson could have envisioned.” Webster was the winning lawyer for many of the Marshall Court’s key decisions, including McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819), and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). It is hard to think of one among them that wouldn’t have resulted from Hamilton’s own constitutional reasoning.

* * *

Fittingly, Brands concludes his narrative with a careful retelling of the early stages of the debate over the Compromise of 1850, which tried to hold the Union together in the face of disputes over whether slavery would expand into the new territories recently acquired from Mexico. Clay was the first to speak, proposing eight resolutions that he hoped would settle all outstanding questions connected to slavery. He asked his fellow senators to join him in a willingness to sacrifice something of their “feelings” to save the Union.

Calhoun, in the last stages of tuberculosis, responded with a speech read by Virginia Senator James Mason. In characteristic style, Calhoun answered, step by step, the question with which he began his address: “How can the Union be preserved?” The short answer was simple: by convincing the South that remaining in the Union was consistent with its “honor and safety.” In that simple phrase, repeated throughout the speech, Clay had his answer: Calhoun would not sacrifice his “feelings.” If, Calhoun concluded, all American territory were opened up to slavery, the fugitive slave clause of the Constitution were properly enforced, the Constitution were amended to restore the sectional balance of power (with some form of Calhoun’s “concurrent veto”), and the North would “cease the agitation of the slave question”—only then could the South be satisfied. Whatever the merits and political prospects of the first three propositions, the fourth was simply impossible. If Southern “honor and safety” required that Northerners ignore slavery, there was no way that Calhoun’s terms could be met.

Nevertheless, Webster, responding to Calhoun, was willing to go further than many of his constituents expected or desired. The South was right, he conceded, to complain of Northern efforts to prevent the return of fugitive slaves. Webster also spoke critically of abolitionists, whose agitation, however high-minded, had only tightened the slaves’ bonds. Extremists on both sides, he argued, caused unnecessary division with their insistence that “what is right may be distinguished from what is wrong with the precision of an algebraic equation.” Calhoun may well have fit that bill, but so did many abolitionists, a moral equivalence that tested the sensibilities of less radical opponents of slavery.

* * *

Remarkably, none of the great triumvirate voted on the final compromise. Calhoun died the last day of March, four weeks after giving his speech. Webster became secretary of state in late July, after Zachary Taylor’s sudden death elevated Millard Fillmore to the presidency. Clay shepherded his omnibus bill through the Senate until a series of votes on July 31 made it clear that no single bill could pass. Exhausted by the effort, he went to Rhode Island to recuperate for a time, leaving it to 37-year-old Illinois Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas to put the compromise in its final form—five bills, not one—and missing the key early votes on these measures. Webster and Clay died just two years later and the ascendency of the third generation was complete.

What did Clay, Calhoun, and Webster leave to their political heirs? No final resolution to the sectional divide, to be sure. Nonetheless, Brands concludes, they “had confirmed [the] freedom” secured by the founders and “guided the Union through four decades of crisis.” The Whig Party, meanwhile, quickly “fell to pieces” without “the leadership of Clay and Webster.” But it is only fair to say that the Whig Party “fell to pieces” in part because of the leadership of Clay and Webster, whose final efforts at compromise could not obscure or adequately answer the fundamental challenge posed to the regime by Calhoun’s defense of slavery. In the most important sense, none of the three was the heir of the founders: willing and able to defend the founders’ regime with the founders’ principles, as John Quincy Adams did in their generation and Abraham Lincoln in the next.

In the end, H.W. Brands has given his subjects their due and perhaps a bit more. Though Heirs of the Founders focuses on their political practice rather than their political thought, it admirably brings to life a neglected period in our history and challenges the reader to reflect upon the conditions necessary to maintain liberty and political Union—questions more relevant in our own day than we would like.