Books Reviewed

Tucker Carlson’s cable-tv show begins identically each night. After the words “Good evening and welcome to Tucker Carlson Tonight”—always intoned and inflected exactly the same way—the host launches into an opening monologue on the news of the day, or what he thinks ought to be the news of the day.

On January 2, 2019, though, there was no news. So Carlson used the holiday lull to deliver a non-stop, 15-minute, 2,571-word evisceration of America’s ruling class—political, industrial, financial, intellectual, and cultural. Our rulers, he insisted, had failed at their ostensible tasks: to improve the health of the country and the lives of its citizens.

The show is usually leavened throughout with puckish humor. Not that night; Carlson was deadly serious. He laid at the feet of our ruling class a devastating litany of failure: the destruction of the family, skyrocketing out-of-wedlock births, the opioid crisis, rampant male unemployment, the sleazy effort to anesthetize the dispossessed with payday loans and pot, increasing financialization and techification of the economy and resultant wealth concentration, and foreign war without purpose, strategy, victory, or end.

But have our rulers really failed? Not if one understands, Carlson explained, that their real aim is to enrich themselves and maintain their power: “We are ruled by mercenaries who feel no long-term obligation to the people they rule.”

Within a day or two, the speech had gone viral. Friend and enemy alike referred to it simply as “Tucker’s Monologue.” Everyone knew instantly which was meant. To those sympathetic, here was a quasi-Trumpist rallying cry not merely for a new Right, but also for millions of apolitical Americans who feel—rightly—abandoned, even preyed upon, by the status quo. By contrast, those opposed sensed a clear danger: a message that—unlike the stale tenets of Republican-study-group, think-tank conservatism—might actually have a chance of inspiring and creating a new majority.

Carlson is the first to admit that he used to be one of the very people he now skillfully criticizes. His first job out of college was at the now-defunct conservative magazine Policy Review. He was one of three staff writers present on day one of the Weekly Standard’s 24-year run.

Still, he was always a bit out-of-step with his colleagues. “I started out as a libertarian,” he recently told me.

I’m still an instinctive libertarian. I have no interest in controlling other people and I don’t care to be controlled. But for a long time, I overlooked all the implausible aspects of libertarian theory. I just believed. I didn’t realize I was a living parody. I thought I was an iconoclast but in truth I was just another member of the herd.

He’s certainly iconoclastic now. The ways in which he breaks—on his nightly show and in bestselling book, Ship of Fools—with the rightist iron triangle of Republican politicians, conservative donors, and the magazine-think tank industrial complex are legion.

Why is capital taxed at half the rate of labor, Carlson asks, and is manifestly unsatisfied by the conventional Right’s answer that “investment” is necessary for “growth and innovation.” What good are the latter, he further asks, if all their gains accrue to a narrowing upper slice while those taxed double for working (assuming they can find jobs) can’t afford to share in the supposed glories of late-stage capitalism?

Why are we still making trade deals, three decades (at least) into a manufacturing decline that has devastated entire American industries and hollowed out many of our communities, all the while enriching some of our most determined foes? Why do our politicians insist on getting us into wars we not only can’t win but for which they can’t even define victory?

Above all, why—at a population of 330 million and climbing, with as many as 22 million here illegally—do our elites refuse to do anything whatsoever to control our borders? Indeed, why do they thwart, at every turn, President Trump on this very issue and attack anyone who speaks up for any limit on immigration whatsoever?

What, specifically, changed the mind of the formerly bow-tied boy-Buckley (or as a friend put it to me, “typical conservative dorkwad”) and launched Carlson toward becoming the leading light of a new conservative movement?

“Two things,” Carlson said.

First, the Iraq war. Like most people I knew and worked with, I supported that war. But I wanted to see it firsthand. So in December 2003, I went to Iraq on assignment for Esquire. What I saw was horrifying.

He describes a scene of total chaos and omnipresent mortal danger:

Before Iraq, I assumed that when smart people of goodwill got together, they make good decisions. Seeing Iraq up close was a formative change in my thinking. It demonstrated the ability of smart people to make obviously unwise, faith-based decisions. What actually happened was not what they promised—not even close. That set off a chain reaction in my mind. I was sincerely shocked that the people in charge were actually really unwise. Worse, they didn’t care. They didn’t even try to correct course. The whole thing made me very distrustful of theories.

And the second?

I’ve been going to the same town in Maine for basically my whole life. Not for a week or two now and then, but three or four months a year for 40 years. I watched it change from clean, reliable, orderly, decent, and bourgeois into something different and diminished. Not just poor but degraded. I asked myself “Why is this happening? What led to this? How did this go from being such a great place to such a troubled place? And why is nobody noticing, or pretending it’s not happening?”

Specifically, what does he mean? Alcohol? Drugs? Opioids? Divorce? Illegitimacy? Unemployment? Welfare? “All of that,” he answers. “All of it. And more.”

Attacked from the “Right”

The establishment right’s reaction to any retrospective doubts about the Iraq war tends to fall into one of three categories: furious denunciation for impiety, chin-rubbing about “flawed execution” of a “worthy mission,” or embarrassed silence. They know they’re not on strong ground here.

Which is why they much prefer to denounce Carlson over his indictment of the elites for their domestic failures. Within a day of Tucker’s Monologue, the “Right” rallied—not of course to denounce the decidedly unconservative trends Carlson complained about, but to attack Carlson himself. “Anyone who thinks the health of a nation can be summed up in GDP is an idiot,” Carlson had said. Right on cue, as if to trumpet their idiocy, in rushed a platoon of policy wonks to defend the sanctity of markets and explain why creative destruction should and must apply every bit as much to people, families, and societies as it did to the buggy whip industry.

Bret Stephens devoted an entire column to riffing on a Monty Python movie, as if Carlson’s meaning were such a joke no serious refutation was warranted. (Then why devote an entire column to it?) It’s worth noting that the proffered catalogue of elite beneficence—“capital financing, deregulation, access to global markets, a stable and predictable regulatory and legal environment, IRAs and 401(k)s* * *talented immigrants, global cities, good food, universities that are the envy of the world, record-making growth and a world in which there’s almost no chance of my children being conscripted to fight a war”—while no doubt offered with utmost sincerely, reads like self-parody.

“The Right should reject Tucker Carlson’s victimhood populism” whinged David French, who, when not exploring a presidential campaign, never misses an opportunity to moralistically lambaste those to his right.

Ben Shapiro took it upon himself to school Carlson in the finer points of political philosophy. Carlson, echoing Aristotle, had declared that “[t]he goal for America is both simpler and more elusive than mere prosperity. It’s happiness.” Not so, replied Shapiro. Carlson has this “wildly wrong. The goal for America wasn’t happiness. It was the pursuit of happiness—the framework of freedom that allows us to pursue happiness.”

Odd choice of past tense aside (perhaps an esoteric assertion of American decline?), it’s hard to know whether to call this a tautology or a hair split so fine it would make Bill Clinton blush. On the one hand, of course it’s true that the Declaration of Independence promises not happiness but only the right to pursue it. The American founders were wise enough to know that no government can guarantee happiness, and that any attempt to do so leads inherently to overreach, opportunity cost, and tyranny. Yet the founders emphatically believed—as they said in that selfsame document—that the purpose of government is precisely “to effect [the people’s] Safety and Happiness.” Moreover, they knew—as George Washington put it in his First Inaugural Address—that “there is no truth more thoroughly established, than that there exists in the economy and course of nature, an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness,” that happiness can be achieved only atop a bedrock of virtue—precisely those virtues whose decline Carlson’s monologue mourns—and that therefore not only can government not afford to be indifferent to virtue, it must actively promote it.

The question—are Americans happier when welfare, child support, cheap consumer goods, and fentanyl replace jobs, families, and meaning?—is precisely the right one, for statesmen and thinkers alike. Our politicians (we have no statesmen) have long ignored it. Their objective is to get reelected, exercise power, and enrich themselves. Our intellectuals insist it’s the wrong question. Any state that concerns itself with the happiness of its citizens, they say, is ipso facto a nanny state, and they know that’s wrong because Hayek, Friedman, Buckley, Goldwater, Reagan, etc.

Not to begrudge any of these figures their genuine accomplishments. But to answer a question with a question: do any of their answers meet the questions of 2019? The answer to that may not quite be an unqualified “no,” but add the qualifier “urgent” to “questions of 2019” and it becomes hard to answer “yes.”

Many conservatives instead try to turn Carlson’s question back on him. When Americans sink into welfare, booze, drugs, video games, and lethargy, who’s to blame? Why, they are! And, to an extent, they’re right. Everyone is responsible for his own choices, his own behavior.

But why don’t these conservatives apply this logic to the ruling class? If men’s free will is to be interpreted to mean that each man is entirely responsible for every outcome of his life, why do we have political leaders at all? If our political officials’ role is not to promote—to create conditions for—the virtue that is indispensable to happiness, what is it? The “conservative” doctrine of “moral agency” taken to its extreme ends up being indistinguishable from total free agency, i.e., libertarianism. Which is to say, doctrinaire, extreme, purity-obsessed, big-picture-denying, and silly.

De Facto Leader

Which is why Tucker Carlson has become the de facto leader of the conservative movement—assuming any such thing can still be said to exist. He didn’t seek the position. I doubt he wants it. He’d probably disclaim it, in fact. But the mantle settled on him nonetheless, partly by default, though it’s more than that.

First, there’s the show. Carlson is something of a Rush Limbaugh for the Trump era. Granted, his audience is not as large as Limbaugh’s at his peak (north of 20 million) or even Limbaugh today (around 15 million), but in an age of media proliferation, fragmentation, and “cocooning”—paying attention only to those few programs that seem narrowly tailored to speak to you directly and personally—Carlson’s audience is impressive. He hosts on any given day the best-rated news-commentary show on cable, averaging around 3 million viewers and on big nights exceeding 5. On one recent night, his single show beat CNN’s entire primetime lineup combined. Ship of Fools reached number one on both Amazon and the New York Times bestseller list, and bumped Bob Woodward’s Fear from the latter.

Second, Carlson’s message is in tune with the times. Limbaugh became famous in part by grasping, early, where conservatism was headed in the immediate post-Reagan era. Carlson is similarly more in tune than anyone else with the mix of populism, economic centrism, immigration restrictionism, and war fatigue that motivates today’s disaffected Right.

Third, like Limbaugh, Carlson did not come to his position of leadership by helming a magazine or a think tank (though, being a former magazine writer, Carlson’s career is slightly closer to that model than was Limbaugh’s). Mostly owing to his prep school background and wardrobe, Carlson is occasionally compared to William F. Buckley. Yet if another, more illuminating comparison may be made, it is that both rethought earlier positions over the course of their careers.

But these similarities obscure very great differences. Not to take anything away from Limbaugh, whose talents as a broadcaster are immense, but he essentially inherited conservatism from Reagan and Buckley owing to their advancing age and his relative youth. He didn’t change or challenge the tenets of their conservatism; he made himself their new champion. And his ascendency was warmly welcomed by the old guard. Also, Buckley’s journey—for instance, on racial issues—was mostly in keeping with that of other conservative luminaries, elite opinion, and the culture at large, and thus (mostly) praised by them all. Carlson by contrast has—apart from his considerable fan base—been vilified for his changes of heart. Interestingly, the Reagan-bots who took it upon themselves to take on Tucker’s Monologue were all a good deal younger—some by decades. Millennial and Gen Z conservatives are sticking up for a status quo that was fading before they were even born, whereas the TV host (age 49) who actually saw the Reagan era firsthand is the champion of a youthful intellectual and political realignment.

In perhaps his most famously enigmatic remark, Aristotle asserts that “natural right is changeable.” This is hardly the place to attempt to plumb the depths of that idea. Yet it is useful in helping us understand why Carlson is both correct and conservative, while his detractors fall short on both counts. The conservative ideas that they venerate originated at specific times to address specific circumstances and challenges. Tax cuts made sense in 1980, when the top marginal rate was 70% and the American economy needed to achieve the escape velocity to leave behind stagflation. Low tax rates are not the most urgent priority when the richest Americans are taxed only on the carried interest of their two-and-twenty, when the share of wealth income controlled by the One Percent has more than doubled since 1980. Carlson gets this. His ankle-biter critics don’t. Like Reagan, Carlson prioritizes the conservation of the actual American nation: its people, communities, traditions, and liberties. That’s what conservatism should be about. All policies—even the best—are just tools to conserve things higher than themselves.

At Home and Abroad

In Ship of Fools’s first chapter, Carlson explains, indirectly, the reason why his heresy is hated. Entitled “The Convergence,” it describes what has been variously termed (though not by him) the uniparty, the junta, the oligarchs, or the ruling class. That is to say, the people who take pains to appear “diverse” on the outside but who in fact all think alike and work together toward the same end: total domination of our country. Conservative intellectuals remain junior—very junior—partners in this coalition; their assigned role is to punish dissidence and enforce conformity by knifing their ostensible co-ideologists in the back.

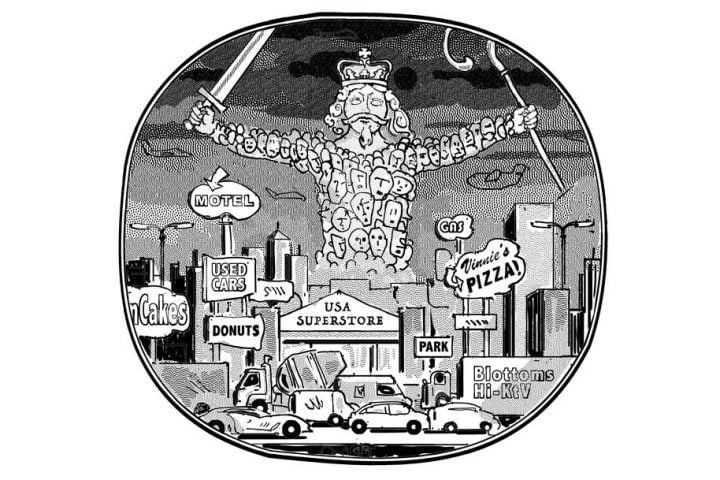

“It looks like a low-I.Q. cable news bestseller” another friend said to me of Carlson’s book. He has a point. The format is smallish, nine by five-and-a-half inches, typical of books deemed unserious by their own publisher. It’s got one of those endless subtitles, so common nowadays, insisted on by marketing departments to remove any possible ambiguity from the title; and its actual words, in the great tradition of cable news subtlety and understatement, warn ominously that America is on “the brink of revolution.” The cover features garish caricatures of eight political and high-tech bosses (plus one leading intellectual, Bill Kristol, Carlson’s former employer). Even the paper is cheap and smells like decaying newsprint.

“But,” my friend quickly added, “it’s not. It’s actually very smart.” That it is, and crisply written. Flipping to the acknowledgements in back, one notices the pointed absence of any reference to a ghostwriter, however euphemistically described. Decades on television have not atrophied Carlson’s ability with the word processor. To the contrary, his style is lean and clean, stripped of all extraneous ornament, a skill perhaps honed writing those monologues. On TV, every second—and therefore every word—counts. Veer astray and viewers click away—and most don’t come back. It’s a testament to his skill that Tucker’s Monologue held so many viewers rapt for so long. It’s not uncommon, in fact, for his monologues to stretch past the ten-minute mark.

Ship of Fools is, in a sense, a guide to the show. The themes it details, Carlson explores every night. But unlike nearly all other cable news bestsellers, low-I.Q. or otherwise, it stands independently of the show, and indeed of the host. One could read this book never having seen the show, even not knowing who Carlson is, and still profit and learn from it.

Six of the seven chapters cover a single topic each: immigration, foreign adventurism, political correctness and thought control, the elite strategy of “diverse and conquer,” feminism and sex, and finally the difference between sincere conservationism and the modern environmentalist cult.

Ship of Fools’s treatment of immigration in its second chapter, “Importing a Serf Class,” is highly informative and entirely correct. “My views on immigration come from growing up in California,” Carlson told me.

People want to make it about race, but it’s not. When I was a kid, my best friend was Mexican. Granted, he was rich, his parents were from the Mexican upper class. But still. The point is, when you allow more poor people into your state than you can assimilate, you create poverty. Unchecked immigration wrecked the state—100%, immigration did that. Whatever the ruling class did to California, I don’t want it to do to America.

“Conservatives,” of course—recent rightward feints aside—are mostly all for mass immigration. “I was too, once,” Carlson says. “But I care more about tactile reality than about theories. The think-tanks are all about theories. Those organizations have become poison.”

The third chapter, “Foolish Wars,” is immensely entertaining, especially to those exasperated by the antics of sanctimonious ex-conservative Max Boot and self-appointed savior-of-conservatism Bill Kristol. Carlson has both dead-to-rights on their innumerable errors and unshakeable self-confidence. Yet this is the one chapter that left me slightly unsatisfied, the same feeling I occasionally get when the show turns to foreign policy. Carlson is undoubtedly right to call out the failures of the last two decades and to hold to account those failures’ biggest cheerleaders. He is especially devastating when he shows how—and how many of—those failures were the direct result of hubristic, imperial overreach so vast it would be comic had its results not been so tragic. Still, I can’t shake the impression that he sometimes goes too far in the other direction. The vanishing America he so ably defends—the country of manufacturing jobs and a thriving middle class—is a commercial republic whose health and prosperity require a muscular foreign policy and strong defense. We still have interests and we still have enemies. Carlson sees this clearly in the case of China, less so when it comes to Islamic radicalism. He is surely right that retrenchment from idiocy is necessary and long overdue. But it would be foolish—perhaps not as foolish as Boot-Kristolism, but foolish nonetheless—to risk our interests and embolden our enemies by overcorrecting.

Fight the Power

Immigration and foreign policy are relatively well-trodden ground, though. It is in the book’s final four chapters that Ship of Fools really shines and, if it does not quite break new ground, at least exposes to a much wider audience ideas hitherto known only in dissident quarters of the right.

Carlson is merciless on our tech overlords and their transparent—but still widely overlooked or denied—effort to work hand-in-glove with the rest of the ruling class to control all speech and thought in what used to be called “the West.” A recurring segment on his show is called “Tech Tyranny” and that’s not hyperbole. The “deplatforming”—from Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Amazon—of dissidents and even skeptics of the ruling orthodoxy continues and accelerates. Disfavored individuals and groups increasingly find themselves locked out of the banking system, unable to book hotel conference rooms, or travel abroad.

This alarms the residual libertarian in Carlson. (It should also be noted that Carlson’s concern for liberty doesn’t end with speech; he’s also a stalwart and consistent defender of gun rights.) The authoritarians in the ruling class aren’t merely all for it; they’re behind it. As for the “conservatives,” all they can muster is the tepid talking point that, so long as the private sector is the actor, then the holy market has spoken and who are the rest of us to judge? That America has de facto ceded many of society’s most fearsome powers—some of which the state is explicitly enjoined from exercising—to corporations, which are using them the way the Chinese Communist Party uses the Chinese state, seems to trouble our conservatives not at all. (Though Bill Kristol did recently call for “regime change” in Beijing. One wonders if he could ever be roused to call for it in Palo Alto.)

Carlson is also more than skeptical of the promises of automation-driven techtopia. No one will have to work! our overlords enthuse. To which Carlson objects: we’ve actually already seen what happens when people don’t work. They become unhappy and self-destructive. How is that a good thing?

The book’s fifth, and best, chapter explains in nauseating detail one of the reasons for our elites’ obsession with “diversity.” Some of them no doubt believe every word of the dogma they force on the rest of us. But the cleverest of them also know that promoting diversity is a key to maintaining their power. The less the disaffected have in common, and the more they squabble among themselves, the less of a threat they pose to the ruling class. Our country has been, and continues to be, disunited on purpose. That’s the hidden fourth motive—after importing Democratic voters, welfare state clients, and cheap labor—for our elites’ stalwart support of mass legal and illegal immigration. The prospect that liberal luminary Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., warned about in 1991 (“disuniting America”) is now official policy of his movement and his party.

As is, via feminism, keeping men and women apart as much as possible and, failing that, for as long as possible. Among the many services Carlson has rendered to his country is getting the concept of “hypergamy” into the bloodstream. Readers of this august journal will have seen the term before (“A Woman in Full,” Spring 2015). To refresh memories, it means that women prefer to date and mate up, but never or rarely down, on the socio-economic ladder. Carlson broached this taboo in his monologue, remarking that

when men make less than women, women generally don’t want to marry them. Maybe they should want to marry them, but they don’t. Over big populations, this causes a drop in marriage, a spike in out-of-wedlock births, and all the familiar disasters that inevitably follow—more drug and alcohol abuse, higher incarceration rates, fewer families formed in the next generation.

This naturally set the feminist furies after him, not for the first time. The sisterhood also gets angry whenever he talks about the plight of men (again, drugs, booze, unemployment, welfare, loneliness, early death), which he does a lot, and thank goodness because hardly anyone else will dare. None of the critics can deny or refute the statistics Carlson cites. They just riposte with “Poor men!” and similar sarcastic jibes. Which is clarifying. If you’re still confused as to whether old-fashioned America’s leftist enemies wish us harm and think we have it coming, just ask them. Increasingly, they’ll tell you to your face.

Without Apology

Indeed, Carlson gets “in trouble” a lot, if we understand the term to mean ginned-up, phony controversies designed to drive him off the air. One of the most effective, sadly, was the response to Carlson’s assertion that mass illegal immigration makes America “dirtier,” by which he meant strewn with litter. Now, this can easily be confirmed by simply visiting and observing places where illegals transit and settle. Anyone from California has known this since at least the 1970s. But the illegal alien is a sacred object in the current year, a saint whose purity cannot be questioned, much less criticized. Carlson’s enemies saw an opportunity, pounced, and cost him a few advertisers.

Their more recent attempt had a happier ending. Democratic Party adjunct Media Matters for America (MMA) assigned one of its 20-something grunts to go back and listen to hundreds of hours of Carlson’s old shock radio appearances. They thought they hit paydirt with a collection of about a dozen outré quotes. A rollout was carefully planned, in conjunction with corporate-Left media (CLM) allies, above all, the Washington Post. The quotes were aired over a succession of days, with the Post alone covering the “story” with an average of three articles per day for a week, including an embarrassingly fawning “profile” of the researcher that read like it was drafted by MMA itself.

Carlson, to his great credit, declined to play his assigned role of groveling penitent. Rather than explaining, or much worse, apologizing, he counterattacked against phony outrage culture and the rotten collusion between the Democratic Party, left-wing agitprop groups, and the CLM. Within a week, the story had blown over and Carlson was still on the air, having lost no further advertisers.

Still, as he said to me, “It’s hard to do a TV show these days.” It’s mostly not hard, actually, so long as you either repeat ruling class talking points or else offer diversionary nonsense. It’s only hard when you take on the ruling class every single night and—more to the point—attack them repeatedly at their weakest points: their dishonesty, venality, greed, stupidity, and myriad failures.

It’s a measure of the effectiveness of Carlson’s criticisms that the opposition fears and hates him so much. He is, more or less, alone out there. And while 3 million viewers sounds like a lot, in a country of 330 million, how impactful is that really?

Judging by the consistent anger Carlson arouses, one must at least entertain the possibility that the ruling class is right to fear him. Carlson and his show are the tip of the spear in a spiritual war, the most effective voice of the disaffected, despised, left-behind, forgotten America that our elites have manifestly failed. The ruling class knows this. Its leftist handmaidens know it. They can’t beat him on the field of ideas. Not simply because he’s smarter and wittier than they are, but more fundamentally because he’s right and they’re wrong. And they know it. As Carlson put it to me:

On some level, they know they’re rotten. They know their gains are ill-gotten and not deserved, the result of bleeding middle America dry. But rather than accept responsibility, what do they do? They blame middle America. They hate middle America because they shafted middle America. Think about it, who do you hate the most? You hate the people you wrong. You get mad at family members more when you wrong them than when they wrong you. It’s the same dynamic. Grown-ups can admit it and apologize. The ruling class can’t.

The ruling class and its social-media-mob bodyguard hates Tucker Carlson not simply because they know he’s right, but because they know he’s effective. The greatest danger to the ruling class is that his message spreads: to other hosts, other shows, other networks, other media and—most dangerous of all—more people.

Especially people in power. Buckley and Limbaugh had their Reagan. Carlson keeps a respectful distance from Trump, praising the president when and where he thinks warranted while remaining unafraid to criticize. Not for any typically conservative reasons but mostly because of what he sees as Trump’s incomplete success—and even, sometimes, apparent lack of interest—in implementing his own 2016 agenda.

If Trumpism is to survive Trump, it will need an intellectual movement, a political party, and above all a new champion. Which raises the questions: Will anyone emerge as Carlson’s Reagan? If not, will he do it himself?

I asked him that, and while he didn’t exactly slam the door airtight, nobody who’d like to see him go into politics should feel encouraged. Others are going to have to carry the political struggle forward. But those others are nearly certain to emerge. My unscientific impression is that the disaffected youth are much more interested in Carlson and his ideas than in warmed-over Reaganism. That Conservatism, Inc., can’t stop dishing out the latter, like a days-old special that always fails to sell out, ensures its looming irrelevance. The kids couldn’t care less about tax cuts, deregulation, and Russophobia.

Carlson’s book, show, and worldview point the way forward. Put people and families first. Remember that the economy exists to serve us and not the other way around. Stop importing scab labor and scab voters to enrich and empower the ruling class. Honor and enforce the fundamental charters of our liberty, especially the first two amendments to the Constitution. Treat people fairly and—truly—equally: no special treatment, no protected classes. Unite Americans around a common destiny.

If we want to avoid the revolution that the subtitle of Carlson’s high-I.Q. cable news bestseller promises, that’s the only way.