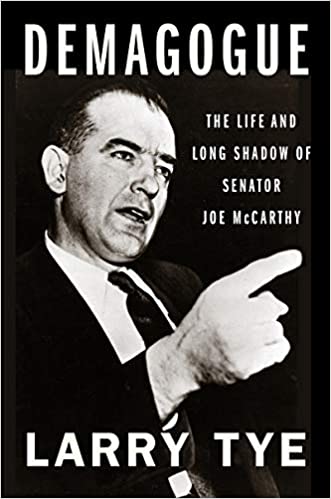

Book Reviewed

Writing history is not as easy as people sometimes think. Many assume it’s simply a matter of assembling a jumble of facts in chronological order, lacing the narrative with insights borrowed from academics and other authorities, throwing in one or two truly sensational details, and then rounding it all out with comparisons to contemporary events to make it relevant to readers. In fact, though, the real labor of history has little to do with writing down the brute facts of the past. It’s about understanding why people back then acted or spoke as they did, which means understanding the context in which events arose and unfolded. Explaining this context to readers is hard work and doesn’t come as easily as praising or blaming historical figures for what they did or didn’t do.

Unfortunately, there’s not much evidence that former Boston Globe reporter Larry Tye has put this kind of thoughtful work into his new biography, Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy. Senator McCarthy’s notoriously obsessive search for Communist agents in the federal government gave birth to one of the most chilling “‑isms” in modern political language: McCarthyism. Tye has bravely ventured into the McCarthy papers at Marquette University, which are largely a giant scrap heap of news clippings and copies of speeches. But he shows no sign of having peered into the rich FBI records and newly declassified sources that augmented the last serious biography of McCarthy, M. Stanton Evans’s Blacklisted by History (2007). Instead, Tye’s account rehashes the familiar research—and judgments—of previous McCarthy detractors and biographers. Tye himself has little to add except numerous oral interviews and email exchanges with figures including (for reasons not explained) Senator Susan Collins of Maine, and Michael and Kitty Dukakis. Demagogue also suffers from a fatal reverence for the opinions of mainstream journalists from the McCarthy era.

***

Those reporters had managed to overlook or downplay the most extensive infiltration and subversion of American government institutions by a foreign power, namely the Soviet Union, in American history. Joe McCarthy, Wisconsin junior senator from 1947 until his death in 1957, came late to the party: by the time he started his investigations, as Tye duly acknowledges, the 200 or so Soviet espionage agents working in the government had been captured, expelled, or neutralized. That included the most dangerous of them all, the State Department’s Alger Hiss. But McCarthy understood that those who had allowed this disgraceful and dangerous situation to develop had to be held accountable. That meant, above all, the political party that had been in power during the years leading up to and during World War II: the New Deal Democrats. McCarthy’s method of hounding these Democrats led to his downfall and ultimately discredited his cause. Nonetheless, the burden of moral failure falls more heavily on those whom McCarthy pursued than on McCarthy himself. Decades of critics who have tried to suggest otherwise have obfuscated the historical truth.

***

Joseph Raymond McCarthy was born on his father’s farm outside Appleton, Wisconsin, on November 14, 1908. Detractors have searched high and low in these humble beginnings for evidence of the man they would come to despise. But in fact Joe McCarthy was a happy, hard-working teenager capable of handling multiple jobs at once—including running his own chicken farm. McCarthy himself was deeply aware of the social gap that separated him from most of his contemporaries in ’50s Washington. At one lavish Georgetown party, he was overheard remarking, “I wonder what these people would think if they knew I once raised chickens.” McCarthy’s Wisconsin farm roots certainly separated him from patrician opponents like President Harry Truman’s Secretary of State Dean Acheson and Senators Millard Tydings and Prescott Bush (grandfather of George W. Bush). On the other hand, his Roman Catholicism bound him early on to a powerful set of allies: former Ambassador Joe Kennedy and his children. One of those children, Jack Kennedy, became a McCarthy supporter from across the Senate aisle and tactfully avoided having to vote for McCarthy’s censure in 1954 by claiming a last-minute illness. Another Kennedy, Bobby, went on to serve on McCarthy’s investigative staff.

The young McCarthy was profoundly ambitious. At age 21 he balanced work with completing his high school education; then he earned a law degree at Marquette while working full-time at a gas station. When World War II broke out, McCarthy served with the Marines in the Pacific Theater as a second lieutenant intelligence officer. Like many other previous biographers, Tye makes much of the fact that McCarthy later exaggerated the number of bombing missions he went on. Nonetheless, he did fly enough missions to present himself plausibly as “Tailgunner Joe” in his Senate campaign against one of the most famous names in Wisconsin politics: Robert La Follette, Jr., son of Washington and Wisconsin legend “Fighting Bob” La Follette.

Going up against La Follette was a mad scheme for someone with no real political experience. But McCarthy’s manic energy, plus a series of bad breaks for La Follette and his campaign, tipped the scales. To everyone’s surprise except his own, McCarthy won and headed to Washington along with other returning veterans, the so-called Class of ’46 (including former Navy officers Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy). McCarthy was eager to stand out from the bright and energetic pack he’d joined. In 1949, he made a disastrous attempt to do so in the soon-to-be infamous Malmedy trials.

***

Malmedy, Belgium, had been the site of a massacre of American POWs by Waffen-SS soldiers during the Battle of the Bulge in 1944. Headline stories in some newspapers hinted that some of the Nazi officers responsible for the killings had had their confessions beaten out of them. Although there was no doubt they were guilty, the German officers’ mistreatment looked to Tailgunner Joe like a clear miscarriage of U.S. military justice. Coming from a state with a large number of German-American voters, he jumped at the chance to join the Senate subcommittee investigation of the charges in 1949. Tye is not the first to suspect some ideological connection between McCarthy and the Nazis on trial. But Tye rightly concludes there’s no evidence to support such allegations. Rather, McCarthy naïvely hoped that attacking the Malmedy Nazis’ mistreatment would earn him plaudits with voters and colleagues. This backfired. It also revealed an ugly side of the volatile McCarthy personality. He bullied and angrily dismissed witnesses who didn’t answer his questions the way he hoped; he quarreled with colleagues, including fellow Republicans; he stormed out of sessions to denounce the proceedings to the press as “a farce.” Already he was showing signs of the psychological imbalance and alcoholism that would haunt him the rest of his career.

Even before the smoke had cleared from his Malmedy debacle, however, McCarthy had found another scandal to sink his teeth into. It was one ready-made for someone bold, reckless, and untutored in the ways of Washington. By 1950 the Venona Project, a counterintelligence program which decrypted messages from Soviet spy agencies operating out of the Russian embassy in Washington, had uncovered at least 200, and possibly 400, active Soviet espionage agents in the United States. The existence of Venona was not public knowledge. What was public was the testimony of witnesses, including former Communist spies Hede Massing and Whittaker Chambers, who had contacted and worked with these agents.

When McCarthy became interested in the subject, there had already been a series of investigations by Congress and the FBI. The most shocking result of these probes was the conviction of Alger Hiss, former undersecretary of State and darling of the Democrat foreign policy establishment. Hiss had been outed by Chambers, his former co-conspirator, thanks to persistent efforts by none other than Richard Nixon. It’s true, as Tye says, that the threat of Communist espionage was already abating when Hiss was convicted in 1950 of perjury for denying his Communist Party membership, but Tye consistently understates the level of that threat, absurdly asserting that Communism couldn’t do any serious damage to America because declared Communists made up only .06% of the population.

***

It was the undeclared communists who were the real worry, including government officials like Hiss and Harry Dexter White, undersecretary of the Treasury. McCarthy grasped that the issue by 1950 wasn’t just Communist subversion. It was the Democrat establishment’s failure to do anything about it during 18 years of running Washington. The Roosevelt and Truman Administrations had shown unaccountable passivity in the face of secret operations at home that served the interests of America’s most dangerous foe abroad. A blue-ribbon commission headed by naval war hero Admiral Chester Nimitz (the existence of which Tye ignores) found that the government’s loyalty program to screen out Communists and other potential security risks had largely been a failure.

To any Republican, this was a national scandal waiting to be exposed. McCarthy took the plunge with a Lincoln Day speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, in which he declared, “I have here in my hand…a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working for and shaping policy in the State Department.” This sensational claim led to a general uproar. Democrats and the Truman Administration hit back with a subcommittee, led by Senator Millard Tydings (D., Maryland), to investigate not the charges McCarthy had made, but McCarthy for making them. At first, his opponents angrily dismissed the notion that he even had a list. Then they complained that if he did, he never explained whether it contained 205 names, as some sources reported, or 57 names, as others claimed. There were in fact at least two lists: one prepared by a former FBI agent named Robert Lee in 1947 for the House Appropriations Committee, detailing examples of poor security screening at the State Department, and another supplied by Secretary of State James Byrnes to a congressman in 1946, detailing some 284 cases of security risks inside the Department. Tydings and the Democrats were determined to argue McCarthy must be working from the Lee list, which was out of date and had already been investigated by the House. But McCarthy was too clever to be caught by this clumsy stratagem. He presented to the Senate a list of names drawn up from various sources that went far beyond the Lee list, apparently confirming what everyone knew but had failed to say: that the leaky security check system installed by the Democrats allowed more than a few highly suspect individuals to slip through the net, as Alger Hiss had done.

***

The storm center in the Tydings hearings was the case of Johns Hopkins Professor Owen Lattimore. Tye prefers to treat Lattimore as Lattimore treated himself: an innocent victim of McCarthy’s slander. In fact, it was Lattimore’s memoir, Ordeal by Slander, that first coined the term “McCarthyism” in 1952. But he was far from innocent. He may not have been “Moscow’s top spy,” as McCarthy initially claimed, but Lattimore was far more than the academic consultant he pretended to be. His pro-Communist and pro-Soviet leanings were already notorious enough in 1941 for the FBI to consider interning him in the event of a national emergency. Yet he had served as FDR’s chief advisor on China. His writings, particularly in the journal of the Institute of Pacific Relations, Pacific Affairs, had helped to shape the idea that Mao Zedong represented China’s progressive future.

Lattimore had always been careful to hide his allegiance to the Communist Party behind a façade of scholarly authority, as did another on McCarthy’s list: State Department China hand John Stewart Service, who secretly provided classified documents to Philip Jaffe, co-founder of the journal Amerasia, in order to encourage a benign view of Mao and his comrades. Stewart’s antics eventually cost him his job, but not before the FBI realized that Jaffe was directly connected with Soviet intelligence. By unintentionally highlighting the case histories of “useful idiots” like Lattimore and Service, the Tydings committee accidentally helped make McCarthy’s name.

Then, on June 25, 1950, North Korean forces launched a surprise attack on their South Korean neighbors and the Americans who occupied the region. In a few weeks the North had pushed U.S. forces down to a tiny enclave at the tip of the peninsula; the Cold War had suddenly turned very hot. The surprise attack, and America’s subsequent near-catastrophic defeat, seemed to prove the gravity of McCarthy’s case against the Democrats, who paid the political price for the Korea debacle. Then-Secretary of State Dean Acheson, Defense Secretary George Marshall, and President Truman are seen today as Cold War stalwarts. That was not, however, how they seemed in the summer and fall of 1950. The Truman team’s incompetence and neglect seemed rather to have made possible not only the Communist invasion of Korea, but also Mao Zedong’s takeover of China in 1948 and the descent of the Iron Curtain across Eastern Europe after 1945. McCarthy’s claim that Democrats were in Moscow’s pocket seemed plausible to many Americans as an explanation for the disaster. His denunciation of Acheson as the “Red Dean”; a long, rambling speech portraying Marshall as an unwitting tool of Moscow (although it was McCarthy’s colleague William Jenner, not McCarthy, who called the famous general “a living lie”); and his attacks on China advisers like Lattimore and Service, had a sudden credibility they completely lack today.

***

The immediate fallout came in the midterm election of 1950. It was a decisive Republican sweep, including the defeat of Senator Tydings by Joe’s handpicked candidate, John Marshall Butler—sweet revenge indeed. But the real turning point came two years later, when McCarthy’s growing prominence as anti-Communist crusader and scourge of the Democrats played a key part in Dwight D. Eisenhower’s victory, making him the first Republican to win a presidential election since 1928. Ike handed McCarthy the chairmanship of the Senate’s Committee on Government Operations and its Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI)—ironically, Harry Truman’s old investigative subcommittee. This gave McCarthy virtual carte blanche to expand his queries into Communist infiltration of the federal government, together with subpoena powers to back them up.

Remarkably, Government Operations and PSI would be the only real positions of power McCarthy would ever hold, with the narrow scope of investigating federal government misconduct (as Tye rightly acknowledges, efforts to tie him to Hollywood blacklisting or other alleged excesses of the era have no foundation). McCarthy’s remarkable gift for publicity, including squeezing the most advantage out of the thinnest possible case, got him hated in liberal establishment circles, but it warmed the heart of Republican voters. What Tye misses is that it was not McCarthy’s cause but his method—focusing on maximum publicity for himself with minimum care and preparation for the cases at hand—that would ultimately lead to his downfall.

***

When McCarthy accused Democrats of being soft on Communism, and some of them of even being Communists themselves, the public was ready to believe him. But when as chairman of Government Operations and PSI he started accusing Republicans in the Eisenhower Administration of being soft on “Communists and crooks,” his credibility plunged. Above all, his choice to target the U.S. Army after 1952 was a fatal error. Some of McCarthy’s charges were certainly true—e.g., that the Army had harbored security risks within its ranks. It was a bureaucratic organization as capable as the State Department of serious errors in judgment, including promoting an obvious Communist fellow traveler like Army dentist Irving Peress to the unearned rank of major. (I was the first to go through the declassified record on the Peress case, and I discovered that almost all of McCarthy’s accusations of bureaucratic malfeasance were true.) But by picking on the U.S. Army, McCarthy made an enemy of President Eisenhower, who gave the Wisconsin senator just enough publicity rope to hang himself. His bull-in-the-china-shop approach, and his attacks on Ike’s idol George Marshall, helped bring the entire McCarthy show to an end.

In 1954 Roy Cohn, one of McCarthy’s top lawyers, was investigated for allegedly attempting to use the threat of a full-press, Reds-under-the-bed investigation into the Army to get McCarthy aide David Schine a draft deferment. The nationally televised hearings revealed McCarthy at his worst: exhausted and spitting mad at perceived mistreatment by the press, McCarthy at one point lashed out at the Army counsel Joseph Welch’s staffer, Fred Fisher, as a Communist sympathizer. (Fisher had been a member of the National Lawyers Guild, a Communist front.) Welch’s measured response—“Have you no decency, sir, at long last?”—became a byword in American politics.

***

By 1954, the world had changed. Peace had come to Korea; Stalin was dead; Ike was firmly in charge of Washington. The fears and alarms that had sustained McCarthy’s rise were dying away—thanks to some degree to McCarthy’s own efforts to get America to arm itself against the internal threat. Now all the figures in Washington he had offended and alienated, including many Republican Senate colleagues, were able to plot their revenge with Ike’s secret encouragement. In November 1954 they delivered a vote of censure that signaled his political extinction. Grief and bitterness over censure destroyed him in more ways than one: three years later, his physical and mental decline and spiraling alcoholism sent him to his grave.

His funeral in Appleton was attended by an unexpected visitor, Bobby Kennedy, who had briefly served on McCarthy’s committee staff alongside Roy Cohn, and who had been a decade-long friend of McCarthy. The Kennedy factor poses problems for Tye, the author of an admiring biography of Bobby. On the one hand, Tye would prefer that his hero had no association with a miscreant such as McCarthy; on the other, there is no getting around the fact that Kennedy saw in McCarthy the kind of tough iconoclast he aspired to be himself. Nor can Tye evade the fact that the Kennedys respected McCarthy’s anti-Communist credentials. When then-Senator John Kennedy heard someone make a remark comparing McCarthy to Alger Hiss, he retorted, “How dare you couple the name of a great American patriot with that of a traitor!” When RFK spoke to some reporters shortly after the censure vote, he told them, “OK, Joe’s methods may be a little rough, but after all, his goal was to expose Communists in government—a worthy goal.” This was a generation of Democrats who saw Communism as the same kind of mortal threat that Nazism had been. When a local reporter spotted Bobby at the funeral (Tye chooses to omit the incident), Kennedy asked him to keep the visit a secret. Later, Kennedy wrote of McCarthy in his private journal:

He was a very complicated character…. He was sensitive and yet insensitive. He didn’t anticipate the results of what he was doing. He was very thoughtful of his friends and yet he could be so cruel.

Joe Kennedy, Sr.’s view of his former friend (McCarthy often played shortstop on the Kennedy’s family softball team) was more prosaic: “I thought he’d be a sensation. He was smart. But he went off the deep end.”

***

How much damage did Joe McCarthy really do—not just to individuals who came under his investigatory scrutiny, but to the country? As I once explained in Joseph McCarthy: Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America’s Most Hated Senator (1999), about 10,000 Americans lost their jobs because of their direct or indirect affiliation with the Communist Party during the so-called Red Scare of the 1940s and ’50s. Of these, 2,000 had worked in the federal government. Joseph McCarthy was responsible for perhaps 40 of those people being fired. In only one case—that of Owen Lattimore—did McCarthy’s accusations actually lead to legal proceedings. In all, fewer than a dozen Americans ever did time for espionage activities on behalf of the Soviet Union (one of them was Alger Hiss, who was convicted before McCarthy appeared on the scene). Only two, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, were ever executed.

This compares to the three and half million Soviet citizens who were sentenced to the Gulag during Joseph Stalin’s Great Terror, of whom at least 680,000 were executed in 1937-38 alone. And yet it is McCarthy who is almost universally denounced as the evil grand inquisitor and unscrupulous demagogue. (Ironically, the fact that no one did go to jail on his watch is used against him as evidence that he never actually caught any Communist spies). As the years rolled on, his opponents and targets like Lattimore and Service began to enjoy a verdict of “innocence by association”: to be attacked by McCarthy became a badge of honor indicative of a clean bill of moral as well as legal health. That bill would be extended even to obviously guilty parties like Hiss and the Rosenbergs. The American Left quickly learned to use McCarthy as a means to discredit the anti-Communist cause as a whole. Today, even mentioning that someone was in fact a member of the Communist Party, such as Barack Obama’s mentor Franklin Davis, isn’t just bad taste but an exercise in—of course—McCarthyism.

Hence we have to conclude the worst damage McCarthy did was to his own cause, as well as to his own political party. Conservative Republicans instantly went on the defensive after McCarthy’s fall. For more than 60 years, his fate gave liberals, Democrats, and the media a kind of moral ascendancy over the Republican Party—an ascendancy confirmed by Watergate and the downfall of another old “Red Hunter,” Richard Nixon. Democrats rarely had to explain their motives or the consequences of their disastrous actions and failed policies, whether it was the war in Vietnam or the war on poverty. Republicans learned it was best to go along to get along in a polity that seemed to move farther left every year. Those who resisted were branded McCarthyites or, latterly, racists.

This was the fraudulent moral order that McCarthy’s disgrace enabled, while his tactics gradually achieved a new level of perfection—or outrageousness—among liberals, who deployed guilt by association, personal smears, deliberate disinformation, and fake news against nearly every Republican president from Nixon to George W. Bush. In the past four years it has reached an appalling level of perfection. Donald Trump’s hand-picked national security advisor was convicted of perjury on obviously fabricated evidence, one of his Supreme Court nominees was accused of rape on no evidence at all, and a once-distinguished magazine, the Atlantic, printed the anonymously sourced libel that Trump himself had called dead American heroes suckers and losers.

Unsurprisingly, Larry Tye tries his best in Demagogue to compare McCarthy to Trump. Events surrounding the outcome of the 2020 election will only inflate the comparison, even as Republicans disavow their former champion as they did McCarthy. But in historical terms this linkage is valid only in an ironic sense. Far from being McCarthy’s principal imitator, Trump is probably McCarthyism’s most egregious modern victim.