Books Reviewed

Long before his last name became a verb in the Oxford English Dictionary, Robert Bork had already enjoyed a distinguished career as a scholar and public servant. Now a distinguished fellow of the Hudson Institute and professor at Ave Maria School of Law, his latest book is a sprawling collection of the writings he has produced over more than four decades. Its publication offers us the opportunity to think about questions that citizens of a constitutional republic have a duty to think about.

Who among us—of a certain age, at least—can forget our current vice president’s role in derailing Bork’s Supreme Court nomination? Or the late Teddy Kennedy’s not quite measured claims that

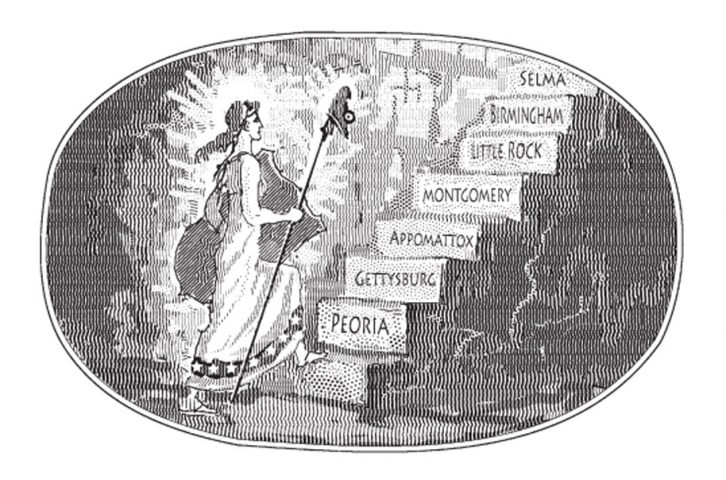

Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the Government, and…

and indeed.

The Bork nomination was a watershed event, one of those “eureka!” political moments for so many people who came to know—in a visceral, publicly televised, in-your-face sort of way—that there is something truly rotten about the manner in which a lot of people view the Constitution, including the constitutionally appointed gatekeepers on the federal bench.

As the Obama Administration looks forward to appointing judges who, in the words of our president, have “the heart, the empathy, to recognize what it’s like to be a young teenage mom, the empathy to understand what it’s like to be poor or African-American or gay or disabled or old,” Robert Bork belongs increasingly, at least in certain respects, to what Joseph Story in the 1830s called “the old race of judges.” He is of the race that cares about constitutional originalism—about constitutional text, tradition, logic, and structure, instead of an ever-evolving model of a “living” Constitution that grows and flourishes so as to sanction, or indeed require, the latest innovations demanded by the elite avatars of cultural radicalism.

Aside from being a vital prod to informed reflection on the politics of judicial nominations and constitutional originalism, A Time to Speak also proves to be essential reading for anyone interested in the full range of Bork’s thought. Included within its covers are some of his constitutional briefs and oral arguments, his opinions as a federal appellate judge, his articles and essays on everything from antitrust law to natural law, and a few memorials and witty remonstrances.

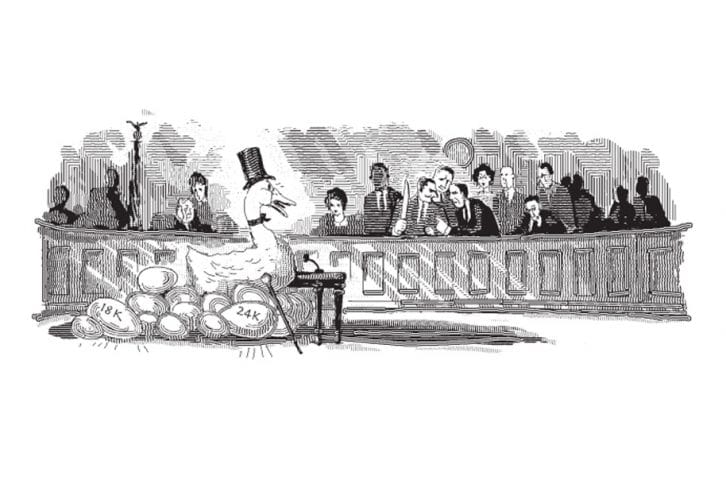

Bork holds up inconvenient truths to those who would embrace the version of judicial progressivism that claims enlightened interpretation of a living constitution is more democratic than strict construction. Do the people really want to do all the wild, wonderful things that so many judges claim they want to do—such as restricting capital punishment (a punishment that is several times explicitly mentioned in the Constitution’s text)? If they do, asks Bork, then why don’t they just get on with it, and leave the judges like the Maytag repairmen of old, with nothing to do?

As he notes in dealing with the use of foreign law in U.S. decisions, some of our jurists’ decidedly un-American attitudes stem from the fact they have simply determined we are not as advanced as our European or Canadian friends, whose progressivism offers a guide to where we are headed. There is a symmetry between this argument and the one he made in an earlier book, Coercing Virtue: The Worldwide Rule of Judges (2003), that the example set by U.S. courts helped transmit the virus of judicial activism abroad. Alas, in an endless cycle of ever-expanding demands on our Constitution, American courts now catch radicalized and transmogrified strains of the very virus they spread.

Judge Bork deserves credit for reinvigorating in legal circles an idea that had once been taken for granted: constitutional interpretation must have recourse to one or another form of originalism in order to be legitimate. If it does not, we live under a rule of men rather than law.

* * *

But many conservatives rightly have bones to pick with what they take to be his unremitting legal positivism. In making the case for originalism in an influential 1971 law review article, he went so far as to say: “There is no principled way to decide that one man’s gratifications are more deserving of respect than another’s or that one form of gratification is more worthy than another.” Yet any serious, or even not so serious, student of philosophy knows there are many principled ways to do just that. The fact that there is disagreement over the right way is no proof that there isn’t a right way. As Bork’s intellectual foils—including Harry V. Jaffa and Hadley Arkes—have pointed out, if conservative jurisprudence attaches itself to such legal positivism, it will have nothing to say on many matters of moral consequence.

The Constitution assumes—and the founders explicitly elaborated—the idea of a morally ordered universe. The Constitution guarantees a republican form of government because its authors understood the republican form to be in accordance with the pre-political laws of nature and nature’s God. We therefore enjoy the right of consent not simply because the Constitution positively guarantees it. Rather, the Constitution positively guarantees it because it is a natural right. So to be a positivist is not really to be a proper originalist; at most, it is to be a stunted originalist, incapable of bringing careful moral reasoning to bear on cases where the Constitution is ambiguous or silent.

The Constitution does not explicitly guarantee the right of a man and a woman to enter into a marriage. Does this mean that Congress or a progressive-leaning state could ban the practice, perhaps as a way of guaranteeing equal dignity and respect to those who are not married or cannot be married? As the Constitution assumes a morally ordered universe of consenting human beings, so it assumes that this very same moral order precludes our consenting to that which is inappropriate to our nature as human beings. The simple fact is that any jurisprudence or political theory—if it is to avoid not simply the imposition of “the judge’s own values,” as Bork fears, but of morally reprehensible values—must ultimately bottom itself on a theory of human nature. Hence the natural rights theorists are quite a bit more respectable than Bork allows.

Bork maintains that “[c]ourts must accept any value choice the legislature makes unless it clearly runs contrary to a choice made in the framing of the Constitution.” But this raises the question not only of exactly which choices our founders made, but why they made them, and why they thought they could not “choose” to do otherwise. As Harry Jaffa notes in a reprinted exchange with Bork, “It is just as illegitimate for a conservative to deny rights that are recognized by the Constitution as it is for liberals to invent rights not recognized by it.”

Bork seems to think that a “natural law judge” would necessarily make “new constitutional principles.” But there is a difference between a “new” constitutional principle and a principle embedded in our constitutional order and evidenced by the very nature of that order. Our founders knew it was best not to try to spell out each and every such principle textually, given the infinite variety of circumstances with which a prudent interpreter of the Constitution—judge or statesman—might be faced.

Now it is quite true that advocates of a natural law or natural rights jurisprudence still have much heavy lifting to do before they can offer concrete guidance on the many actual constitutional disputes that come before courts. As Bork notes, it is not sufficient that such advocates confine themselves to clarifying the moral and constitutional absurdity of Justice Taney’s majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857)—though even this has some value against contemporary liberals who insist on embracing Taney’s reasoning that the Constitution as originally drafted did, in principle, protect slavery.

A proper natural law or natural rights jurisprudence would hardly be a license for judicial supremacy, as Bork fears—assuming the other branches are doing their jobs. A vigorous exercise of constitutional powers to contain judicial hubris—including executive refusal to enforce unconstitutional judgments, and Congress’s power to limit appellate jurisdiction and impeach judges—would go a long way to damping such fears. These and other powers would be the enforcement arms of a sober departmentalism, in which each branch takes seriously its role as an expositor of constitutional meaning. As Abraham Lincoln noted in his speech on Dred Scott, the general policy of the country should not be controlled by a Supreme Court decision that is contrary to “legal public expectation” and the established practices of the departments, and in addition evinces false historical claims and deep disagreement among the justices themselves.

* * *

But conservatives should not allow their important disagreements with Bork to overshadow the immense debt of gratitude we owe him for giving us a high-profile model of a judge whose distinctive judicial virtue is not his empathy, but his intellectual seriousness in interpreting the Constitution as a document that sets the metes and bounds of our public life together—rather than as an empty vessel into which any judge may pour his postmodern concoctions.

Even as Bork goes astray, he reminds us what we have in common. In the book’s last entry, we see his flawed application of the “original understanding” principle to the martini. He rightly condemns those “activist bartenders” who imposed on us the chocolate or raspberry “martini” in lieu of the actual beverage as it was originally understood by its founders. He then goes on, however, to condemn the olive, declaring that the strict constructionist response to such a thing is to say, “When I want a salad, I’ll ask for it.” That is rather like saying, when asked if one wants water with his scotch, “I’m thirsty, not dirty.” But while the interpretive principle on which the latter remark rests clearly holds in any originalist or common-sense understanding, no fair-minded martini drinker would banish the olive. Still, though conservatives may argue, they can also agree, with Cornell professor emeritus Werner Dannhauser, that even the worst martini is better than no martini at all.

And so we should take this opportunity to reflect on how much better a place the Supreme Court would be if Robert Bork were sitting on it today, with more than two decades’ worth of his constitutional wisdom on record. Anthony Kennedy, the man who eventually acceded to the Court in the wake of Bork’s doomed nomination, has voted to reaffirm Roe v. Wade, create a constitutional right to homosexual sodomy, declare the death penalty to be unconstitutional for any crime other than murder, and establish a generalized right of habeas corpus for enemy alien combatants who have never set foot on U.S. soil. It is hard to imagine Bork voting for any of this nonsense, much less acquiescing in the absurdly tortured constitutional reasoning that is the hallmark of Justice Kennedy’s opinions.

We therefore can only pray that Robert Bork does not, like Story, “stand…with a pained heart, and a subdued confidence,” as he reflects that he is among the last of the old race of judges. And we pray that heaven forfend the day when the chocolate martini is not merely sanctioned, but required under a thoroughly strained reading of the equal protection clause.

* * *

For Correspondence on this essay, click here.