Books discussed in this essay:

Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point, by Lewis E. Lehrman

Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, by Garry Wills

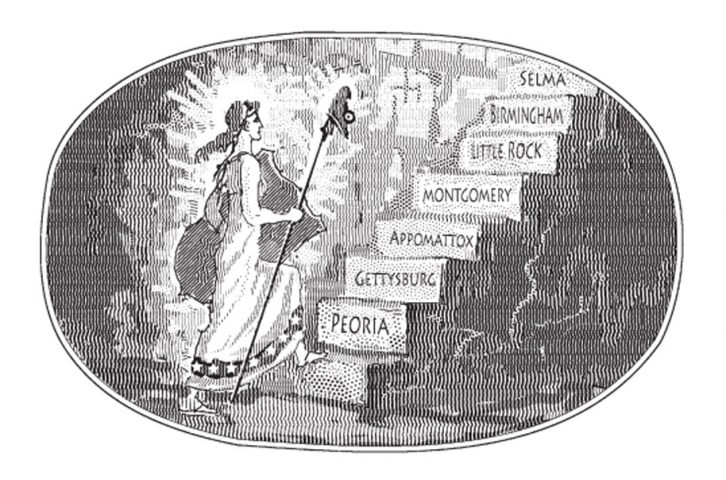

A friendly critic has recently characterized my life’s work as dedicated to the moral vision of Athens, Jerusalem, and Peoria. Of course, as a faithful student of Leo Strauss, I recognized and welcomed the association with Athens and Jerusalem, but I had not hitherto thought of adding Peoria to the two Heavenly Cities. I have no doubt, however, that what Abraham Lincoln accomplished at Peoria, and because of Peoria, has been embellished by heavenly scribes on the gates of immortality. As we contemplate the 155th anniversary of the magnificent speech that catapulted an Illinois lawyer into national politics and helped change the course of a nation, we are indebted to Lewis Lehrman for focusing our attention on what the angels have always known.

An investment banker and former New York gubernatorial candidate (he lost narrowly to Mario Cuomo in 1982), Lew Lehrman has had a deep, abiding interest in American history and in Abraham Lincoln in particular. His far-sighted intellectual and philanthropic projects include the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History (with Richard Gilder); the Gilder Lehrman Collection, a treasure trove of American historical documents now on deposit at the New-York Historical Society; and the Lincoln Institute he created to support scholarship on the 16th president. Now, Lehrman has given us in Lincoln at Peoria a full-length treatment of the 1854 speech that marked Lincoln’s initial confrontation with the fateful question of slavery expansion.

A Giant Swindle

The Gettysburg Address is almost universally admired, but seldom, if ever, understood. As an example, we offer Garry Wills’s Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America (1993). This is a book so bad that it ought never to have been published. Yet it received a Pulitzer Prize! This tells us more about the academic establishment behind the award, than it does about the book. Here is the heart of Wills’s opinion of Lincoln’s masterpiece:

He altered the [Constitution] from within, by appeal from the letter to its spirit, subtly changing the recalcitrant stuff of that legal compromise, bringing it to its own indictment. By implicitly doing this, he performed one of the most daring acts of open-air sleight-of-hand ever witnessed by the unsuspecting. Everyone in that vast throng of thousands was having his or her intellectual pocket picked…. Lincoln had revolutionized the Revolution, giving people a new past to live with that would change their future indefinitely.

Some people, looking from a distance, saw that a giant (if benign) swindle had been performed…. Heirs to this outrage still attack Lincoln for subverting the Constitution at Gettysburg—suicidally frank conservatives like M.E. Bradford or the late Willmoore Kendall.”

Wills calls the Gettysburg Address a “giant swindle.” This phrase came from Kendall who, being “suicidally frank” did not call it or believe it to be “benign.” Wills tacitly confesses that he inserted “benign” only to avert suicidal consequences. There was however nothing suicidal about Kendall’s frankness. Kendall, like Bradford, was a resolute and unapologetic defender of the slavery of the antebellum South. He was a disciple of John C. Calhoun, who had denied any truth to the equality proposition in the Declaration of Independence, and had denied as well that the doctrine of human equality had played any role in the framing or ratification of the Constitution. Calhoun was the father of that state-rights conservatism which justified nullification, secession, and the indefinite extension of slavery. His heirs—Kendall and Bradford among them—have opposed every attempt by the Congress or the Supreme Court to implement the equal protection clause of the 14th amendment, the voting rights of the 15th amendment, or any other attempts (e.g. school desegregation) to bring about a color-blind Constitution. Calhoun is also the intellectual forbear of those “confederates in the attic” who believe as fervently that the South will rise again as that there will be a Second Coming of their Messiah.

The Gettysburg Address came a little less than a year after the Emancipation Proclamation. The new birth of freedom to which Lincoln asked us the living to be dedicated was, at the time, most uncertain. The president did not believe that the freedom promised by the Emancipation Proclamation could survive the war—and the end of his war powers—without a constitutional amendment. This was certainly the most urgent of the unfinished business in his mind. He did not live to see the three Civil War amendments, but there can be no doubt that they would all have met with his approval.

The amended Constitution that emerged from the war, with the abolition of slavery and the promised abolition of discrimination by race, was certainly different from the Constitution that was framed and ratified in 1787. It took nearly a hundred years for Congress to enforce the promises of the 14th and 15th amendments. But the Civil War amendments, with the legislation that completed them, were certainly implicit in the idea of the “more perfect Union” envisaged by the framers, because the meaning of that more perfect union was implicit in the doctrine of human equality in the Declaration of Independence. Nowhere is Lincoln clearer or more forceful in expounding this connection than in his Peoria speech, delivered a decade before Gettysburg.

Wills here cites Kendall on Lincoln’s alleged re-founding of the Constitution: “Abraham Lincoln and, in considerable degree, the authors of the post-civil-war amendments, attempted a new act of founding, involving concretely a startling new interpretation of that principle of the founders which declared that ‘all men are created equal.'” Kendall writes of “all men are created equal” as if it had never before Gettysburg referred to Negroes, or to their individual rights as human beings, and had never implied any idea of equality between the races. Kendall and Wills apparently assume the truth of Chief Justice Taney’s opinion in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857), that under the Constitution of 1787, black men and women were believed to be “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Taney implied that the difference between whites and blacks was thought in 1787 to be as great as that between a horse and its rider. Kendall and Wills also accept Jefferson Davis’s emendation of Calhoun, according to which the equality in the Declaration referred only to collective rights of peoples, but not to the rights of individual human persons. That is to say, it meant that the people of America were equal to the people of Great Britain, but it had no reference to the equality of individual human persons to each other. Hence it did not mean that any human beings as human beings had any right to be governed only with their own consent. Hence it did not condemn slavery. That is the crucial point contended for by Davis, Kendall, and Wills. In their view the original founding, including the Declaration of Independence, did not condemn slavery.

According to Wills, the new founding, of which Lincoln was supposedly the great progenitor, was rooted in the invention of a meaning to the proposition that all men are created equal which it had never before possessed. He would have us believe that Lincoln’s literary skill had deceived the American people into believing that the words of the Declaration meant something that no one had ever before imagined them to mean. This is however a lie as big as any invented by Joseph Goebbels in the service of the Third Reich.

In a sequel to the foregoing, Wills writes of the Gettysburg Address that

Its deceptively simple-sounding phrases appeal to Americans in ways that Lincoln had perfected in his debates over the Constitution during the 1850’s. During that time Lincoln found the language, the imagery, the myths that are given their best and briefest embodiment at Gettysburg…. Without Lincoln’s knowing it himself, all his prior literary, intellectual, and political labors had prepared him for the intellectual revolution contained in those fateful 272 words.

It is certainly true that all Lincoln’s prior labors had prepared him for Gettysburg. But in the Address there is no intellectual innovation of any kind. Lincoln’s political labors were manifested in great and powerful speeches and public letters that had reached nearly every literate American by 1863. The secession of the 11 Confederate states was motivated precisely by the conviction that Lincoln’s election was intended to mark the beginning of the end of slavery in America. The House Divided speech had explicitly called for the “ultimate extinction” of slavery, and was one of the great motivating forces for secession. Ending the extension of slavery was to be the first step in that direction. Wills’s absurdity is also manifested in the fact that the Republican Party, in the platform upon which Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860, quoted verbatim the whole of the statement of principles in the Declaration of Independence—including the proposition that all men are created equal—and declared that these principles were embodied in the Constitution. The Constitution that Wills says was sprung on a gullible public at Gettysburg was openly and manifestly present in the 1860 election. No one was fooled by the Gettysburg Address, and it is only historical illiteracy and ideological perversity that could make possible the award of a Pulitzer to Garry Wills’s giant swindle.

Unraveling Compromise

The subtitle of Lew Lehrman’s book is The Turning Point. The Peoria speech was a turning point in Lincoln’s life and career because it represented a turning point in the life of the nation. In retrospect, after two world wars, in which a United States that had abolished slavery played a decisive role, we can say that it represented a turning point in the history of Western civilization. Although he had always been personally antislavery, and had occasionally expressed his antislavery opinions in public, Lincoln had not been an antislavery politician. The Whig Party, to which he belonged for 25 years, had subsisted on an intersectional basis, in which the Northern and Southern wings tacitly agreed to keep slavery out of party politics. A similar truce had characterized the Democratic Party. It was agreed generally (except by abolitionists) that under the Constitution the states had exclusive jurisdiction over their domestic institutions. The abolition of slavery in the Northern states after 1787 had taken place exclusively through the action of the states themselves. No political question could arise in Congress or in presidential politics concerning slavery within a slave state. Lincoln once remarked that he had no more right to interfere with or responsibility for slavery in South Carolina than for serfdom in Russia.

The extension of slavery into territories, where the character of new states would be determined, was a different matter. The policy of the founding generation concerning slavery in the territories appeared to be set by the Northwest Ordinance, first enacted in 1787 under the Articles of Confederation, and reenacted by the first Congress under the U.S. Constitution. This celebrated measure, which to this day is called one of four “organic laws” in the United States Code, outlawed slavery in a region that in time became the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. This act, as Lincoln understood it, set the founders’ seal on the policy of keeping slavery out of territories as yet uncontaminated by it.

Missouri had come into the Union as a slave state in 1820, but all the remaining Louisiana Territory north of Missouri’s southern boundary was to be “forever free,” a prohibition of slavery known as the Missouri Compromise. It was unnecessary to decide the status of slavery in territories if there was no territory (or very little territory) whose character as to slavery was undecided.

The Mexican War changed everything. Texas, which had been independent of Mexico since 1836, was brought in as a slave state at the start of the war in 1845, with a provision that it might be subdivided into as many as five states. Two years later, the United States had acquired more than 60% of Mexico’s land area as defined by international boundaries. It had enlarged the boundaries of the United States by more than 40%.

In 1849, California—which, like Texas, had been part of Mexico—applied for admission into the Union as a free state. That would break the balance between 15 free and 15 slave states. During the Mexican War, the House of Representatives had repeatedly passed the Wilmot Proviso (named for Pennsylvania congressman David Wilmot), which had declared that in any territory to be acquired from Mexico, slavery should be prohibited. As often as the House voted the Proviso up, the Senate voted it down. The future Republican Party was clearly outlined in the House vote on the Wilmot Proviso. The protection of the interests of slavery was dependent on the control of the Senate. Lincoln’s interest in becoming a United States senator in the 1850s was certainly motivated in part by the fact that the Senate had become a central theater in the conflict over slavery.

Taking the Stage

Lincoln at Peoria is a salutary, forceful reminder of the future president’s powerful entry into the political struggle that led into the Civil War. The importance Lehrman finds in the Peoria speech cannot be exaggerated. It not only marked Lincoln’s entry into the debate over slavery, it marked the first and fullest elaboration of the political, rhetorical, and philosophical strategy that he would pursue to the end of the decade and, indeed, to the end of his life.

During the 1850s Lincoln gave hundreds of speeches, some of them perfunctory, many of them extensive. There are, however, four speeches which possess the foundations of the whole: Peoria in 1854, the speech in 1857 on the Dred Scott decision, the House Divided speech in 1858, and finally the Cooper Union speech in early 1860. The Peoria speech is, however, the foundation of everything that came after it. Lehrman not only elaborates, carefully and precisely, its political and philosophical doctrines, but he traces their presence through the other speeches, as well as into the presidency. It is a book on the whole of Lincoln, seen through the oration that launched him upon his path.

Lincoln did not ordinarily extemporize, except on ground that he had thoroughly prepared, and where he was fully confident. The Kansas-Nebraska bill, which rejected the old Missouri Compromise containment of slavery, became law in May 1854; the Peoria speech was the following October, although the bulk of it had been delivered two weeks before in Springfield. Lincoln had at least four months to prepare. During this interval the volcanic eruption that became the Republican Party had been dominating the political landscape. At Peoria he demonstrated his mastery of all the issues in the events that had transpired.

The Peoria speech surely ranks among the greatest of Lincoln’s, and among the greatest in world history—with the best of Demosthenes, Cicero, or Edmund Burke. How can one explain a text which explains itself with such surpassing power and lucidity? Lehrman has wisely reprinted the complete text, as well as an extremely useful ten-page “Milestones in the Lives of Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas.” Douglas was the main sponsor of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and Lehrman’s “Milestones” is a reminder that the true Lincoln-Douglas debates encompassed all of Lincoln’s speeches arising from the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. (Confrontations between Lincoln and Douglas go back to the 1830s. Lincoln’s 1839 Subtreasury speech was a Whig Party reply to the Jacksonian Democrat Douglas.) Of these the joint debates were only a part. It is remarkable that Lincoln’s justly deserved fame as a debater was earned in combat with this one opponent. Some credit for the heights of his achievement must be given to Douglas’s forensic skill and an unrelenting energy and ambition as great as Lincoln’s.

What That Purpose Is

When Abraham Lincoln stood before the people of Peoria on October 16, 1854, he summed up his indictment of the repeal of the Missouri Compromise as follows:

This declared indifference, but as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I can not but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest. [Italics are Lincoln’s.]

And later:

But one great argument in the support of the repeal of the Missouri Compromise…is “the sacred right of self government.” …I trust I understand, and truly estimate the right of self-government. My faith in the proposition that each man should do precisely as he pleases with all which is exclusively his own lies at the foundation of the sense of justice there is in me. I extend the principles to communities of men as well as to individuals…. The doctrine of self government is right-absolutely and eternally right-but it has no just application as here attempted. Or perhaps I should rather say that whether it has such just application depends upon whether a negro is not or is a man. If he isnot a man, why in that case, he who is a man, may as a matter of self-government do just as he pleases with him. But if the negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself? When the white man governs himself that is self-government, but when he governs himself and also governs another man, that is more than self government—that is despotism. If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that “all men are created equal,” and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.

Judge Douglas frequently, with bitter irony and sarcasm, paraphrases our argument by saying, “The white people of Nebraska are good enough to govern themselves, but they are not good enough to govern a few miserable negroes!”

Well I doubt not that the people of Nebraska are, and will continue to be as good as the average of people elsewhere. I do not say the contrary. What I do say is, that no man is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle—the sheet anchor of America republicanism. Our Declaration of Independence says:

“We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, DERIVING THEIR JUST POWERS FROM THE CONSENT OF THE GOVERNED.”

I have quoted so much at this time merely to show that according to our ancient faith, the just powers of government are derived from the consent of the governed. Now the relation of masters and slaves is, PRO TANTO, a total violation of this principle. The master not only governs the slave without his consent; but he governs him by a set of rules altogether different from those which he prescribes for himself. Allow ALL the governed an equal voice in the government and that, and that only, is self government. [Italics and capitals by Lincoln.]

And I have quoted so much, in part, because the brilliance of the Gettysburg Address often affects readers like a divine afflatus, filling them with an overwhelming sense of purpose, without quite knowing what that purpose is. I am reminded of Jimmy Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, standing in the Lincoln Memorial and reading the Address inscribed on its wall. He is filled with an overwhelming determination to go out and fight government corruption. Of course, we all rightly cheer him on. Yet it might have been better if he had also read the Peoria speech and other writings of Lincoln, as well as some of the writings of the American Founders. Of course, this is not a recommendation for a Hollywood script, but neither is Hollywood’s foreshortening of Lincoln a substitute for genuine understanding.

When Lincoln gave the Gettysburg Address he had the Peoria speech behind him, but also inside of him. The above portions of the speech are not only examples of how Lincoln went about proving his case against Douglas, they are supreme examples of the Socratic art in political literature. They deny any shred of credibility to the thesis that Lincoln at Gettysburg had given a different and unprecedented meaning to the doctrine of human equality. As Lew Lehrman so convincingly shows, there is nothing virtually present at Gettysburg that is not actually present at Peoria.

Initiating the Path

“Allow all the governed an equal voice in the government and that, and that only, is self-government.” From this principle it is clear not only that the slaves ought to be free, but that they must have an equal share in governing. For a government to be dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, those who live under the law must share in making the law they live under, and those who make the law must live under the law that they make. This reciprocal relationship between making and obeying the law is here articulated by Lincoln with matchless clarity. It is implied in all of his invocations of the Declaration of Independence, although he sometimes seemed to take a different view.

Immediately after asserting that all the governed must have an equal voice in government, Lincoln denies that he is “contending for the establishment of political and social equality between the whites and blacks.” Earlier in the Peoria speech, he had denied any intention to bring about such equality, saying that the feeling of “the great mass of white people” was against it. “Whether this feeling accords with justice and sound judgment, is not the sole question, if indeed, it is any part of it. A universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, can not be safely disregarded.”

Later in the speech Lincoln says that

the great mass of mankind…consider slavery a great moral wrong; and their feelings against it, is not evanescent, but eternal. It lies at the very foundation of their sense of justice; and it cannot be trifled with. It is a great and durable element of popular action, and, I think, no statesman can safely disregard it.

We see that he says in one place that a statesman cannot safely disregard the feeling against equality and in another that he cannot safely disregard the feeling for it. We must realize that both assertions are founded in the proposition that the just powers of government are derived from the consent of the governed. The consent of the governed however means the opinion of the governed. But what if—as in this case—the opinion of the governed is itself self-contradictory?

As the Declaration notes, the consent of the governed does not authorize governmental powers that are not just powers. These powers cannot be just powers if governors and governed do not recognize their reciprocal humanity. Lincoln warned time and again that those who would deny the rights of others to life and liberty could not long retain their own. Clearly however the full recognition of the right of equal participation in government of all who are to be governed, is an aspiration, not to be achieved at any or every time and place. By the standards of 2009, and in the wake of the 1964 and 1965 civil rights acts—the citizens of Illinois in 1858 were rabid racists. There was virtually no “consent of the governed” possible to laws that would allow black people to enjoy anything that today would be called civil rights. It is part of Lehrman’s achievement to make us aware of the extent of what Lincoln accomplished at Peoria, initiating the path that would lead ultimately to consent to rights to which no consent was then possible. Garry Wills to the contrary notwithstanding, it was at Peoria that Lincoln set the pathway leading to the Emancipation Proclamation, the Gettysburg Address, the Civil War Amendments, and beyond to the civil rights laws of today. Without Lincoln clearing this pathway, Martin Luther King, Jr., would not have been possible.

Seeds Planted

Perhaps Lincoln’s most effective argument in the moral climate of white Illinois in the 1850s was one that seemed to bypass all questions of the equality or inequality of whites and backs. Whether a black woman was or was not his equal in any other respect, he said, in her right to put into her mouth the bread that her own hand had earned, she was his equal, the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of any man. Here Lincoln was appealing to the passion that above all others made the American Revolution: the passion that said that the fruit of one’s own labors was indisputably one’s own. One’s property might be taxed, but rightfully only by a government instituted to protect that property. Lincoln knew that the black woman could defend her right to put into her mouth the bread her own hand had earned only if she was not merely free, but possessed the vote which alone could give her the power to protect her right—a power which white women, too, did not then possess.

Lincoln knew at the time that only the seeds he planted could lead to results consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Independence. He knew that the last thing he should do would be to forecast those consequences. Throughout the whole of Lincoln’s and Douglas’s encounter in the 1850s, it was the strategy of each man to identify the other with those of his supporters most obnoxious to a notoriously racist public, while denying the charges of the other. Douglas identified Lincoln with abolitionism and racial equality, and Lincoln identified Douglas with the movement to allow blacks, whether free or slave, into territories and Free States where they had not been. Looking back from our long perspective, we can say that each in fact told the truth about the other, and each one lied about himself. Yet surely if ever there were a noble lie in the Platonic tradition, it is Lincoln’s denial of any intention to bring about an equality of political rights between whites and blacks. His denial was an indispensable necessity in bringing about the very thing he denied.

The Peoria speech was what Socrates would call his “second sailing,” Lincoln’s re-entry into political life, to rescue the principles of the Declaration from the reproach of hypocrisy, to complete the work of the American Founders, and to make possible a new birth of freedom. Lincoln at Peoria laid the foundation for the greatest statesmanship the world has ever seen. We are greatly indebted to Lewis Lehrman’s superb book for helping us to understand why no list, however short, of the greatest speeches of all time could omit Lincoln at Peoria.