Books Reviewed

Books discussed in this essay:

The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, by Mancur Olson

Hot, Flat, and Crowded: Why We Need a Green Revolution—and How It Can Renew America, by Thomas L. Friedman

Imagining India: The Idea of a Renewed Nation, by Nandan Nilekani

Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepeneurship and the State, by Yasheng Huang

How Rich Countries Got Rich…and Why Poor Countries Stay Poor, by Erik S. Reinert

Joseph Schumpeter ominously speculated that as capitalism succeeded, democracies in time would come to expect its end (wealth) but reject its means (free-market competition). He worried that because of the inequality and creative destruction it brings, capitalism would provoke a kind of adverse reaction. A popular call would arise for government to plan market outcomes according to some utopian view of society's good, and this democratically guided central planning would inevitably slow economic growth. Schumpeter predicted, in turn, that if economic expansion faltered, individual liberty would be directly imperiled or quietly ceded by citizens resigned to having their diminished economic position protected by the state.

Capitalism as a conception of economic order is still a young idea, perhaps dating from 1776 when Adam Smith described its nature—though curiously the term itself is a gift of Karl Marx. Of all secular ideals it probably has been the most powerful, apart from democracy itself. To Smith the idea was mostly utilitarian—it described an objective reality and set down what have proven to be accurate prescriptions for its continued success, e.g., that free trade with the world yields increased wealth at home. He embraced capitalism as the single most likely way to expand human welfare and commended it enthusiastically to mankind. Marx's counteranalysis, skillfully dressed for its times in scientific language, might be said to have been more politically influential than Smith's. Only a few decades ago, well over half the land mass of the world was in the hands of Marxist regimes. While only five formally Communist countries remain, the world seems hardly done with Marx.

For one thing, though Marxist influence on Progressivism is unknown or denied by modern believers, the historical chain of descent is clear. Its intellectual carriage was the transplanted notion of German socialism that was part of the DNA of Johns Hopkins University at its founding. America's first German-model research institution—the first to provide doctoral study—was Woodrow Wilson's cradle. His Ph.D. thesis famously pronounced the Constitution's checks and balances antique and unsuited to a modern democracy. The University of Wisconsin under Richard Ely, John R. Commons, and Frederick Jackson Turner (all schooled at Hopkins) became the nursery of Progressive ideas as applied to real world politics, which in the state's "legislative laboratory" became known as the "Wisconsin Idea." Robert LaFollette, Victor Berger, and other politicians were intent on creating a socialist polity, not surprisingly in the state with a substantial German immigrant population. Wisconsin supplied more manpower to the New Deal than any other university. In turn, the New Deal philosophy later found its permanent home in university schools of public policy.

This intellectual history may seem superfluous because utopian political movements seldom reference antecedents. They advance by covering their own tracks. And they cynically appeal to emotions, inflaming the envy and misplaced sense of justice that drive demands for the redistribution of wealth. Of course, the practical pursuit of redistribution usually ends up enthroning a mostly well-to-do intellectual elite who enlarge the powers of the state and advance their own social and economic status.

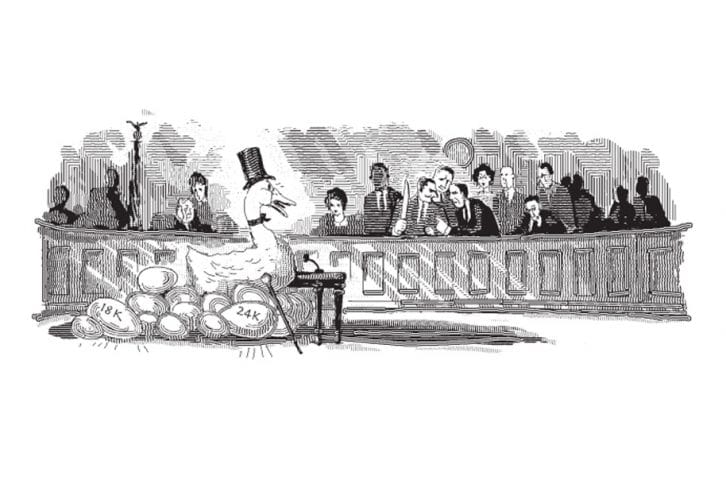

This result was anticipated by Schumpeter and detailed by political scientist Mancur Olson in his classic book The Logic of Collective Action (1965). Olson developed "capture theory" beyond the regulatory context, applying it to the larger arena of government appropriations. Regulatory captures are relatively straightforward and self-limiting: a regulatory agency becomes a prisoner of the industry it's supposed to be regulating, and turns into advocate and patron. Olson's second kind of capture involved interest groups' laying claim to an expanding federal budget for outright payments of federal monies-a more unlimited danger. Thus, many groups pressing a grievance in the name of democracy find funding for their collective activities—including asking for money! —from government itself. Together, these two types of capture have caused a kind of sclerosis that is undoing democratic capitalism.

A Benign Autocracy?

Several new books continue the debate over capitalism and democracy in revealing ways. Thomas Friedman seems to fulfill Schumpeter's and Olson's gloomiest apprehensions. According to Friedman's Hot, Flat and Crowded: Why We Need A Green Revolution-and How It Can Renew America, democracy itself is the problem. This environmental jeremiad is more precisely about how democracy cannot solve the interrelated environmental and population crises in which we are enmeshed. Friedman, a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for the New York Times, argues that democracy—or, rather, American democracy—allowed the horrendous problems of an overpopulated, globally trading, and warming world to emerge. Our free market, unfettered by smart bureaucrats, made the world what it is. And what is it? Ted Turner, who "is not a scientist," is quoted as authority (among endless other friends of the author) when he tells Charlie Rose what the essence of the world's problem is: "Too many people are using too much stuff." This is what happens in free market democracies, Friedman tells us—an unacceptable mess ensues when there are no expert overseers to direct our affairs. Certain rich people, of course, should be left free to use their private planes to fly to New York to tell Charlie that if other people would stop aspiring, our planet would be livable once more.

Friedman's book belongs to the long line of alarmist literature that is by its very nature utopian. Not because it sounds the alarm (many crises real and speculative merit alarm) but because of its restoration perspective. "If we want things to stay as they are [my italics]…things will have to change around here, and fast." In Friedman's view, we need experts to help decipher our crises. Democratically elected leaders are no longer equipped or competent to interpret or shape the new order. Charismatic leaders without office "are critical; they draw attention and passion to an issue." But even people like Al Gore, who plays a major role in the book as an "eco-star," make a difference only if they are followed up by "revolutionary bureaucrats." These heroic types, courageously working at their desks, "with the flick of a pen, can change how much electricity fifty million air conditioners consume or how much diesel a thousand locomotives guzzle in one year. That's revolutionary."

Friedman points admiringly to the ability of totalitarian states to override the desires of their subjects. He quotes the CEO of General Electric lamenting, "Why doesn't America have a government that can just put all the right policies in place to shape the energy market?" This classic statement of business self-interest prompts a late-night "mischievous" reverie by Friedman:"If only…If only America could be China for a day—just one day. Just one day!" Experts—actually, revolutionary bureaucrats—could lay down the new order via permanent regulatory directives. The world would be set right, as it was and should be. The future would look like the acceptable past before too many people started using too much stuff.

In the end, this is a backward looking, confused book. It traffics in the vocabulary of the future, but its message is hopeless unless we plan to discard the Constitution and representative democracy. In Friedman's view, we'd be better off environmentally if intellectual elites could rule us in a benign autocracy. And it likely would be benign, because intellectuals are…so nice.

Messy Capitalism

Two extraordinary books beg to differ. Nandan Nilekani's Imagining India refutes much of Friedman's pop wisdom that democracies cannot be counted on to control population growth and pollution as these need to be controlled. Nilekani, a co-founder of the global software outsourcing giant Infosys, presents a beautifully written systematic treatise on the promise democracy holds for a country that Friedman sees as hopelessly overproducing people and pollution. What looks to Friedman like chaos that must be centrally managed by government experts appears to Nilekani, who actually helped shape his country's emerging market economy, as the kind of democratic messy capitalism that can solve problems. Indeed, the book unabashedly celebrates democracy as the means by which opposing views can be debated and settled. Seeing the promise that free markets hold in the face of what is plainly failed socialism, the author is certain that capitalism will win out precisely because democracy coexists with the freedom that individuals need to make markets work. Nilekani's understanding of the relationship is sensitive and sophisticated. Although he professes admiration for Friedman, he proposes in elegant, powerful prose a frontal challenge to the revolutionary bureaucrat:

It is true that India is a young democracy, saddled with the problems of inexperience, and that it has endured ineffective, populist governments. But the flag-carriers for authoritarian rule should remember that such power is always more dangerous than it is worth. An authoritarian system is always susceptible to tyranny and abuse—it is as likely to produce a Robert Mugabe as a Deng Xiaoping. It also creates errors that cannot be easily corrected, as we have seen in China's response to environmental issues and population growth. The democratic system, despite its flaws, is its own cure—in its guarantee of liberty for all people, irrespective of background and wealth, it offers the real drivers of change that can help overcome entrenched interests, inequities and centuries-old divisions.

The facts are with Nilekani. And he has the knowledge that comes of one's own labors. Infosys is iconic in contemporary India just as IBM, Boeing, and Microsoft have been in the commercial and social history of the United States. To millions of Indians, particularly its vast population of young people, the firm symbolizes the capacity to develop world-class human capital assets and to mount a commercial challenge from within a country that development experts said couldn't compete on the world stage. In the face of resistance from the government's economic planning apparatus, Infosys emerged because of its ingenious exploitation of global technology, most especially communications. The globalization that Friedman frets over was critical to the Indian rebirth.

Friedman's other worries seem feeble as well, as Nilekani's story unfolds. To anyone at all familiar with correlations between income, health status, and family formation, it is not surprising that as India becomes richer its birth rate declines. And as Nilekani suggests, with expanding wealth, India eventually will be able to afford to attend to environmental issues. Already, Mumbai demonstrates that sensible, incentive-based environmental regulation can effect enormous improvements in air quality. One eagerly awaits the American entrepreneur or politician capable of writing such a balanced, enlightened book imagining our future.

China for a Day

Alas for those who would suspend democracy even for a day, Capitalism With Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State makes a powerful case that the China Friedman admires is a chimera. Yasheng Huang teaches international management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In every regard, his book is an example of diligent scholarship. It disturbs American intellectuals' construct regarding China's economic success, and it leaves the reader with a definite sense that running America on the Chinese model would not be such an attractive idea. Among other things, it would not put us on our way to a cleaner environment.

The book describes how in the aftermath of Deng Xiaoping's relaxation of state control of enterprise, a wave of both entrepreneurial activity and democratic self-rule began to emerge throughout China. The ruling elites, driven by concern for the unforeseeable consequences of these developments, launched a program that forced commerce to the easily regulated cities and starved rural areas of capital and government resources. The gleaming cities of China represent the universal drive of bureaucrats to develop regulated, planned environments. As Huang shows, these cities are underperforming economically while the countryside, potentially a much bigger generator of wealth, plummets in income, health status, and literacy. Moreover, in the cities state-sanctioned corruption has arisen, another reliable by-product of a planned economy. Nonetheless, Huang assembles persuasive evidence that growth unsettles autocratic rule.

Thus China emerges as an underperforming economy relative to its potential. Comparing China's economic performance to India's, Huang notes that India has a significant advantage in its "soft infrastructure," that informal set of human capital assets, including the freedom to communicate, that result from India's commitment to democracy. In the end, he sees India as the better performer, a conclusion much at odds with the prevailing view of Western experts.

Getting Rich, Staying Poor

In each of these books, the tension between rural and urban economic activity appears endemic to both successful growth and the propensity to embrace a more or less democratic order. Friedman is sometimes Jeffersonian in his suspicion of city life. Nilekani speaks of India's passage from a similar suspicion of cities to understanding the city as an engine of innovation and locus of social networks. Huang traces China's purposeful tilting of opportunity toward cities to the rent-seeking schemes of political elites. Who would have thought, in the age of the internet, that such issues would appear so important to the balance between capitalism and democracy?

Finally, in his difficult but thought-provoking How Rich Countries Got Rich and Why Poor Countries Stay Poor, Erik S. Reinert argues that George Marshall was the last to have the urban-rural relationship about right when he conceived of German postwar recovery. Reinert, who teaches at Tallinn University of Technology in Estonia, argues that what development economics advances as axiomatic rules of growth have no basis in theory or experience. As a result, many countries, shaped by the Washington Consensus and its successor, the Millennium Goals, have had their development retarded. The implicit message of the development experts is that the underdeveloped cannot emerge. (Reinert comes close to attributing racism to the cadre of international officials who oversee the distribution of aid from the developed world.) The fear of cities and their chaos clashes, in the minds of development experts, with the urge to establish centrally planned economies, which implicitly seek to concentrate economic activity. The result is programs of aid that prove ineffective and, worse, supportive of non-democratic regimes. He considers the ability to develop mixed urban-rural economies as central to stable nation-building, but sees no champions for this option in either international bureaucracies or Economics departments.

Reinert points to the unstated conclusion that the development community is at best ambivalent, and more likely hostile, to capitalism and growth. If democracy seems to accompany capitalism and to allow growth with all its dire environmental and other consequences, then perhaps the experts conclude that democracy, too, will have to go. Schumpeter would not be surprised.