Books Reviewed

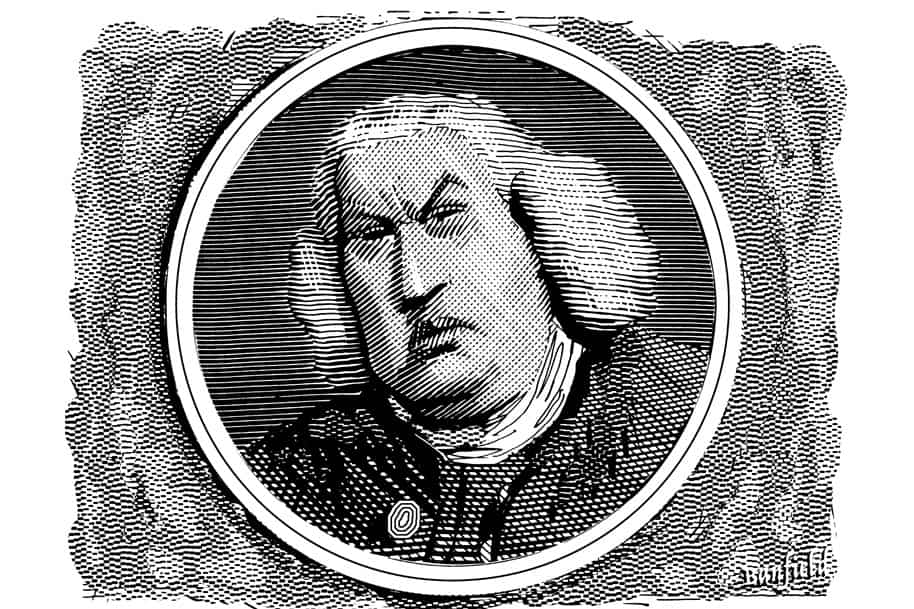

In his day Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) was renowned as the most distinguished English writer of the time, and in our day the 18th century in English literature is customarily spoken of as the Age of Johnson. Yet when one considers the literary forms most esteemed today—novels, poems, plays—his achievement is notably underwhelming. He wrote only one novella, The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia—basically a moralizing tract that takes a dim view of the human condition, with stick figures advancing the argument. One or, at most, two poems have lasted, “The Vanity of Human Wishes” and “London,” if lasting means being enlisted on a forced march through poetic history in English 101. And his one tragedy, Irene, was performed only because England’s most celebrated actor and theater manager, David Garrick, was a lifelong friend of Johnson’s. In its most solemn moments the play set the audience laughing. No one today would dream of staging it and not even Ph.D. candidates trouble to read it any more.

Johnson’s reputation as a writer rests instead on feats of heroic scholarly industry and morally unexceptionable instruction: the Dictionary of the English Language, which remained the standard authority well into the 19th century; the three series of brief essays, some 450 of them, on manners and mores that appeared in magazines weekly or twice weekly over the course of several years; the edition of Shakespeare designed to make reading the plays as exciting and intellectually profitable as Garrick made seeing them onstage; and the collection of 52 critical biographies known as The Lives of the Poets. Lexicographer extraordinaire, paragon of learning, purveyor of practical wisdom to a readership eager for improvement, Johnson was the all-purpose heavy-duty man of letters, and his artistry and force of mind enriched jobs of work that are not generally undertaken by men of his caliber. His singular abilities elevated subsidiary roles in the literary enterprise—editor, critic, journalist—to a height they had never known before and have not reached since. The erudite footnote does not commonly enjoy exalted status among literary genres, but editorial glosses on and emendations of Shakespeare fill two large volumes of The Works of Samuel Johnson from Yale University Press. The usual order of rank does not apply. If Johnson wrote it, it was serious literature.

And when he was written about, that was serious literature too—outstanding of its kind. James Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson (1791) deserves the honor regularly bestowed on it, as the greatest biography ever. Boswell’s Johnson tends to outshine what Johnson set down of himself on paper, for the conversation his friend and devotee recorded—torrential in eloquence, acidulous in wit, relentlessly sensible, electrically alive—is even more impressive than his written prose, whose majestic balanced periods grow wearisome when consumed in quantity.

In Lectures on the English Comic Writers (1819), William Hazlitt, as an essayist a peer of Johnson’s and some would say his superior, put this criticism memorably:

After closing the volumes of the Rambler, there is nothing that we remember as a new truth gained to the mind, nothing indelibly stamped upon the memory; nor is there any passage that we wish to turn to as embodying any known principle or observation, with such force and beauty that justice can only be done to the idea in the author’s own words…. What most distinguishes Dr. Johnson from other writers is the pomp and uniformity of his style. All his periods are cast in the same mould, are of the same size and shape, and consequently have little fitness to the variety of things he professes to treat of. His subjects are familiar, but the author is always upon stilts.

As an essayist, Johnson is best taken in measured doses. Johnson preferred to do his own reading that way. He once expressed surprise when a friend said that when he started reading a book he devoutly finished it. Everyone knew, as Adam Smith once remarked, that Johnson had read more books than any man alive, but he announced blithely that he rarely read a book through to the end: “they are generally so repulsive that I cannot.” He “looked into” books and was often satisfied with a brisk survey of the grounds.

His own books are well worth looking into, again and again. The 1,300-page selection of his writings recently published by the Oxford University Press, in its 21st Century Oxford Authors series and under the editorship of the master scholar of the English 18th century David Womersley, is the most comprehensive volume now available. Only the exorbitant price—it seems fixed for a captive student readership—argues against it. Johnson’s writing is characteristically sober, solemn, grave—even sorrowful sometimes—as he considers the innumerable follies and trespasses of mankind, the eagerness with which men and women plunge into pandemonium, the lies they tell themselves to evade the lacerations of righteous shame and guilt. Johnson’s pessimism was that of a man who knew the world’s cruelty only too well, and who was also a constitutional melancholic or hypochondriac; the two words were synonymous in his time, as his dictionary states. Nowadays, we would call him a sufferer from clinical depression; and that wasn’t the half of it.

Treacherous Waters

Born nearly dead, he contracted scrofula as an infant, a tubercular infection of the lymph glands, also known as “the king’s evil,” which the laying on of royal hands was believed to heal. In the hope of an instantaneous cure, Johnson’s mother took him to be touched by Queen Anne. The cure didn’t take. Eventually the illness resolved itself, but not before Johnson had lost the sight in one eye and much of his hearing; and his face and neck would always bear the scars of its ravages.

Further damage, to his mind and nervous system, occurred when he was a young man. Financial hardship—his father was a failed bookseller—compelled him to abandon his studies at Oxford after only a year. The blow staggered him. The Master of Pembroke College said young Johnson was the most knowledgeable student he had ever seen. An academic career, a comfortable life of untroubled bookishness, had seemed a reasonable prospect. Then the hope was suddenly snatched away, and Johnson, back home in the small town of Lichfield, sank ever deeper into despondency.

His anxieties nourished a host of psychosomatic symptoms—tics, twitches, convulsive jerks, huffing and puffing, mutterings under his breath, idiosyncratic rituals, such as touching every post he passed, and going back if he missed one. The uncontrollable movements and noises made him grotesque to see, and they never went away. His friend the painter Joshua Reynolds observed, “[T]hose actions always appeared to me as if they were meant to reprobate some part of his past conduct.” When the artist William Hogarth got his first glimpse of Johnson, at the home of the novelist Samuel Richardson, Boswell writes, “he perceived a person standing at a window in the room, shaking his head, and rolling himself about in a strange ridiculous manner. He concluded that he was an ideot [sic], whom his relations had put under the care of Mr. Richardson, as a very good man.” Hogarth was taken aback when the supposed mental defective launched into a fiery tirade against the injustice of King George II. “In short, he displayed such a power of eloquence, that Hogarth looked at him in astonishment, and actually imagined that this ideot had been at the moment inspired.” Johnson’s modern biographers W. Jackson Bate and John Wain strongly suspect that his affliction was obsessive compulsive disorder, complicated perhaps by Tourette syndrome.

Johnson endured several years of sepulchral depression—after his father died, he slaved away as a despised underling teaching school—before a turn came for the better. In 1735 he married the widow Elizabeth Porter, whom he called Tetty. He was 25, she 46, and in the description of his friends buxom, blowsy, excessively painted, and given to drink. With her dowry of more than £600—£40 a year was a decent wage—he opened a school of his own; but it never had more than eight students, and was not a going proposition.

In 1737, he left his wife behind temporarily and set out for London with one of his recent pupils, David Garrick. They had one horse between them and arrived with sixpence in their pockets. Garrick was coming into a substantial legacy, so they were not destitute. But he was soon off to Rochester, and Johnson was left alone to seek his living on Grub Street with the swarming multitude of hopeful authors and broken hacks. His first published poem, “London,” an imitation of Juvenal’s Third Satire, measured the hard odds against his making it:

Here malice, rapine, accident, conspire,

And now a rabble rages, now a fire….

This mournful truth is ev’rywhere confess’d,

slow rises worth, by poverty depressed.

A publisher paid Johnson ten guineas for the work, and he was launched—but upon treacherous waters.

He caught on as a factotum with the Gentleman’s Magazine, which Bate calls “the first magazine in anything like the modern sense.” It wasn’t much of a living or much of a life. Tetty hated London and being poor and let him know it. He struggled, floundered, and nearly gave up. He even put in for another provincial teaching job but he lacked the requisite degree. Disappointments mounted. He was brilliant at what he did but grew ever more tired of doing it. From 1741 to 1744 he wrote the “Parliamentary Debates” for the magazine, almost half a million words, which like a cut-rate Thucydides he put in the mouths of orators whose actual speeches the law forbade to be published. The “Debates” were such a success that circulation increased by half. Nevertheless, he continued to perform small jobs, from judging poetry contests to composing Latin verses to writing the introduction to the magazine’s annual compendium. He was always desperately searching out more work; yet when he got it, it was too much for him. Procrastination became habitual, along with the ensuing furious dash to meet the deadline.

In 1746 Johnson began the colossal work he had long contemplated and long put off: the Dictionary. Solvency at last: the publishers paid him £1,575, in installments as he worked, from which he paid his six assistants. The assistants did the scut work of amanuenses; they were down-and-outers, Bate writes, whom Johnson hired mostly out of pity. He expected the task to take three years to complete; it took nine. He did the heavy lifting himself, defining over 40,000 words and providing 114,000 illustrative quotations in many different fields from his immense knowledge of English literature since the Elizabethan age. The quotations often pointed to a moral or underlined a tenet of the faith. For “resurrection”—defined as “Revival from the dead; return from the grave”—he cited among others a pious observation by Isaac Watts that some might find dubious but Johnson took for gospel: “Perhaps there was nothing ever done in all past ages, and which was not a publick fact, so well attested as the resurrection of Christ.” For “gibbet”—“A gallows; the post on which malefactors are hanged, or on which their carcases are exposed”—he took the opportunity, with a snatch of poetry by John Davies, to scorn the reprobates who deny God until their intolerable end is upon them: “When was there ever cursed atheist brought / Unto the gibbet, but he did adore / That blessed pow’r which he had set at nought?”

Boswell justly trumpets “so stupendous a work achieved by one man, while other countries had thought such undertakings fit only for whole academies.” (The French Academy, employing 40 members, had taken 55 years to produce its own dictionary.) Thomas Babington Macaulay, who had many harsh words for Johnson, relented here and called his masterpiece “the first dictionary which could be read with pleasure.” It continues to please.

His Lifework

But pleasure was only incidental to Johnson’s purpose; instruction was his driving force. “It is as a moralist, in the broad sense of the word,” writes Bate, “that Johnson regarded himself.” To read in order to amend one’s own life and to write in order to move other men to amend theirs: these were the fundamentals of his literary project, his lifework. In his eyes, practical wisdom as a Christian understands it—prudence joined to trust in Providence—is the supreme intellectual virtue and the foundation of the righteous life, and it is the writer’s obligation to inculcate it. What commonly passes for intellectual excellence, Johnson advised, is often mere diversion, to use pointedly a word highlighted by Blaise Pascal, whose uncompromising, reverent intelligence Johnson admired greatly. You must read with your whole soul, for your eternal destiny depends on it.

The essays he wrote for the Rambler (1750-52), the Adventurer (1752-54), and the Idler (1758-60) remind the reader again and again what the stakes are as he encounters Johnson in full cry: life is serious, and study is the most serious work you will do if you do it right. Knowledge is not virtue, but virtue alone is the true end of knowledge. Here is Rambler No. 87:

A student may easily exhaust his life in comparing divines and moralists, without any practical regard to morality or religion; he may be learning not to live, but to reason; he may regard only the elegance of stile, justness of argument, and accuracy of method; and may enable himself to criticise with judgment, and dispute with subtilty, while the chief use of his volumes is unthought of, his mind is unaffected, and his life is unreformed.

At their best the essays have the power of shrewd analysis of motive and passionate exhortation to decisive action. They can be severe indeed, and frequently deliver the sting of disdain for failings never to be made good or atoned for in this lifetime. Johnson knows how painful such failings can be because many of them are his own.

Against these transgressions he pits the resources of philosophy reinforced by piety. Philosophy unaided—whether Socratic, Aristotelian, Stoic, or that of the black-hearted infidel Enlightenment—lacks the capacity to produce happiness. Here is Rambler No. 32:

The sect of ancient philosophers, that boasted to have carried this necessary science [of bearing calamities] to the highest perfection, were the stoics, or scholars of Zeno, whose wild enthusiastick virtue pretended to an exemption from the sensibilities of unenlightened mortals, and who proclaimed themselves exalted, by the doctrines of their sect, above the reach of those miseries, which embitter life to the rest of the world.

But even the noblest pagan philosophy crumples under sufficient pain. Christian piety, on the other hand, makes good of evil, and Johnson believes it more natural than Stoic mental fortitude. The indispensable virtues of hope and trust in the Almighty distinguish the reverent mind from the merely philosophical.

The chief security against the fruitless anguish of impatience, must arise from frequent reflection on the wisdom and goodness of the god of nature, in whose hands are riches and poverty, honour and disgrace, pleasure and pain, and life and death. A settled conviction of the tendency of every thing to our good, and of the possibility of turning miseries into happiness, by receiving them rightly, will incline us to bless the name of the lord, whether he gives or takes away.

Johnson’s 1765 edition of Shakespeare’s plays consolidated the public esteem his Dictionary and moral essays had won him. Johnson’s preface is perhaps the most famous piece of Shakespeare criticism ever, and it exalts the playwright as the supreme artist of nature as against artifice. Yet even such supremacy is not without flaw.

His first defect is that to which may be imputed most of the evil in books or in men. He sacrifices virtue to convenience, and is so much more careful to please than instruct, that he seems to write without any moral purpose…. This fault the barbarity of his age cannot extenuate; for it is always a writer’s duty to make the world better, and justice is a virtue independent on time or place.

Evidently Shakespeare’s besetting fault is that his soul is fundamentally different from Samuel Johnson’s: the greatest playwright is foremost a creator rather than a teacher.

It comes as no surprise, then, that in The Lives of the Poets (1779-81) the ultimate literary judgments are moral. Johnson’s highest praise for Paradise Lost is that it is plainly the work of genial holiness: “In Milton every line breathes sanctity of thought, and purity of manners, except when the train of the narration requires the introduction of the rebellious spirits; and even they are compelled to acknowledge their subjection to God, in such a manner as excites reverence, and confirms piety.” That judgment was notoriously reversed by William Blake in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1794): “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devil’s & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devils party without knowing it.” Blake’s preference for Milton’s demonic aspect over his rather sedate godliness ironically fortifies a more conventional literary judgment of Johnson’s on Paradise Lost: “None ever wished it longer.”

Johnson says explicitly that he writes for the ordinary reader rather than for philosophers and poets, and in his biography of Joseph Addison, he demonstrates his particular regard for the literary “masters of common life.” Addison is more celebrated as an essayist than as a poet, and the pieces of his that appeared in the Spectator and the Tatler established in their painless way exemplary standards of manners and morals. Johnson praises Addison in these terms: “No greater felicity can genius attain than that of having purified intellectual pleasure, separated mirth from indecency, and wit from licentiousness; of having taught a succession of writers to bring elegance and gaiety to the aid of goodness; and, if I may use expressions yet more awful, of having ‘turned many to righteousness.’”

Fear of the Lord

As Boswell writes almost mournfully, the fear of impending madness, the wholesale loss of his cherished mental powers, bedeviled his friend. “To Johnson, whose supreme enjoyment was the exercise of his reason, the disturbance or obscuration of that faculty was the evil most to be dreaded. Insanity, therefore, was the object of his most dismal apprehension; and he fancied himself seized by it, or approaching to it, at the very time when he was giving proofs of a more than ordinary soundness and vigour of judgement.”

Patient in affliction with the fortitude of those schooled in suffering, Johnson did not fear dying; but the thought of what was to come after death terrified him thoroughly. The conviction of his unworthiness before the throne of God gnawed at his vitals. Heaven was not for the likes of him, he could be sure, and visions of damnation burned their way into his mind.

The parable of the buried talent was a recurrent motif in his spiritual reckoning. No matter what he accomplished, the thought of the work he failed to do, the gifts he had wasted, mortified him. He understood how wonderful his powers were, and he owed his Maker recompense for the genius with which He had endowed him; but he could never make good the debt. From his youth to the end of his days, his journal entries showed him resolving to get up early every morning to do a full day’s work, and instead lying in bed till the afternoon and not doing half of what he intended. On Good Friday, 1775, when he was 65, he wrote: “When I look back upon resoluti[ons] of improvement and amendments, which have year after year been broken…why do I yet try to resolve again? I try because Reformation is necessary and despair is criminal.” No other writer of comparable greatness hated his work as much as Johnson did, and so hated himself for shirking it. When Boswell wondered aloud why a man of his surpassing abilities did not take more pleasure in writing, Johnson replied, “Sir, you may wonder.” In a really quite characteristic mood he famously declared that no man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money. After the state awarded him an annual pension of £300 for services to literature in 1762, he vowed never to work quite as hard again. But he suffered for his newfound leisure. His incorrigible indolence cried out for chastisement, which he inflicted upon himself.

His too-tender conscience extorted from him an immense sum in psychic pain. He told a friend that if he were to divide his innermost thoughts into three equal parts, two of them would consist of flagrant impieties. His correspondence with Mrs. Hester Thrale, the dearest friend he ever had, who knew him better than Boswell did, suggests that he entertained fantasies of manacles and leg-irons, and the unruliness of his mind appalled him. Yet if he sinned extravagantly in thought, he was near saintly in word and deed. His writing and conversation were perfect and upright, espousing unimpeachable Christian virtues that he actually lived by. He was certain, however, that he fell hopelessly short of the exalted reasonableness and religious sentiment he promoted in his moral essays.

So what if he did; who doesn’t? Self-knowledge on that score was not his strength. Active virtue was. He was the very soul of charity. His benevolence was prodigious. He housed and cared for an assortment of waifs and strays, including a prostitute he had found near death in the street, carried home on his back, nursed to health, and convinced to live a righteous life. Yet nothing Johnson said or did could calm his fear of the Lord’s implacable justice. He knew he was unregenerate, and that was that. He could have used a friend to tell him that if God had wanted him to think himself a worm, He would have made him a worm.

He and Boswell spoke repeatedly of this consuming fear and self-loathing. The tender-hearted biographer gave vivid life to his friend’s mental agonies:

His mind resembled the vast amphitheatre, the Colisaeum at Rome. In the centre stood his judgment, which, like a mighty gladiator, combated those apprehensions that, like the wild beasts of the Arena, were all around in cells, ready to be let out upon him. After a conflict, he drove them back into their dens; but not killing them, they were still assailing him. To my question, whether we might not fortify our minds for the approach of death, he answered, in a passion, “No, Sir, let it alone. It matters not how a man dies, but how he lives. The act of dying is not of importance, it lasts so short a time.”

When Boswell pressed the point, Johnson responded with asperity, showed him the door, and declared they would not meet the next day as they had planned.

Choicest Companion

Johnson must have been in a monumental snit; to deny himself the pleasure of Boswell’s company went against his principle and practice, which valued friendship and conviviality among the finest things in life. Despite the tendency to psychic desolation from which both the biographer and his subject suffered, Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson memorializes much rich fellowship and good humor; Johnson did his best to laugh the demons away. And it was with the choicest companions. As Leo Damrosch shows in his exuberant new book, The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age, Johnson fraternized heartily with some of the most extraordinary men Great Britain has ever produced. The Club was founded in 1764 by Johnson and the great portrait painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, and the members they selected were Oliver Goldsmith, Edmund Burke, Burke’s father-in-law, and three particular friends of Johnson’s, the young men about town Topham Beauclerk and Bennet Langton, and the musicologist and magistrate John Hawkins. After Hawkins fell out with Burke over some now obscure matter, he left the Club, leading Johnson to coin a phrase and proclaim him “an unclubbable man.” The ranks would swell over the next 20 years to include such luminaries as Edward Gibbon, Adam Smith, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and David Garrick, as well as a host of scholars, bishops, lawyers, and physicians now as then less resonant in name than the acknowledged eminences. One blackball was enough to keep out a prospective member, and Boswell, to his chagrin, was at first considered to be insufficiently distinguished for inclusion, gaining admission only in 1773.

The elect would gather weekly at the Turk’s Head Tavern to eat, drink, and launch high talk well into the night. As Damrosch points out, conversation was the Club’s raison d’être, and it was conducted with vigor, wit, and competitive fire—especially on the part of Johnson, who as Boswell observed was given to “talking for victory.” For the sake of sport he would take the side of an argument that appeared less tenable and carry the day with it. Johnson found Burke a nonpareil opponent in this informal and everlasting debate, and he memorialized Burke’s gifts even as he displayed his own: “You could not stand five minutes with that man beneath a shed while it rained, but you must be convinced you had been standing with the greatest man you had ever yet seen.” On the subject of America, however, the two masters diverged so sharply that they tacitly agreed for friendship’s sake never to argue the matter. Burke favored the colonists’ struggle for independence, while Johnson believed them “a race of convicts, [who] ought to be grateful for anything we allow them short of hanging.”

On the matter of religion, Johnson was similarly abrasive in his certitude and unforgiving of free thinkers, such as Gibbon, whom he and Boswell called “the Infidel.” Largely on the advocacy of Oliver Goldsmith, Gibbon was admitted to the Club in 1774, two years before he published the first volume of his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Damrosch notes wryly that this masterpiece would have been sufficient reason to blackball Gibbon, and he cites one of Gibbon’s “rare appearances in the Life,” when Johnson pontificated that historiography was a trifling business, for it took no skill to report facts, and any philosophic inference from the facts was airy nothing. Gibbon sat silent under this assault on his specialty, and Boswell crowed in triumph, “He probably did not like to trust himself with Johnson!”

But if Johnson could show an ornery streak when riled, he was also capable of being the warmest of friends, with an impetuous fondness for innocent rascality. He made Bennet Langton goggle in wonderment as he declared his intention “to take a roll down” a hill at the younger man’s estate; “and laying himself parallel with the edge of the hill, he actually descended, turning himself over and over till he came to the bottom.” Langton told Boswell of the night he and Topham Beauclerk came banging drunk at Johnson’s door at three in the morning to roust him for more drinking, and Johnson answered with a poker in hand, expecting to encounter ruffians. “When he discovered who they were and was told their errand, he smiled, and with great good humour agreed to their proposal: ‘What, is it you, you dogs! I’ll have a frisk with you.’”

Of one day in 1775 Boswell writes, “I find all my memorial is, ‘much laughing.’ It should seem he had that day been in a humour for jocularity and merriment, and upon such occasions I never knew a man laugh more heartily.” The most clubbable of men, Johnson was the presiding figure when friends assembled, primus inter pares at the very least, dominating the event with his readiness of wit, copious eloquence, and laughter. Everyone knew what a man he was, the very best of the best. If only he had known it himself.