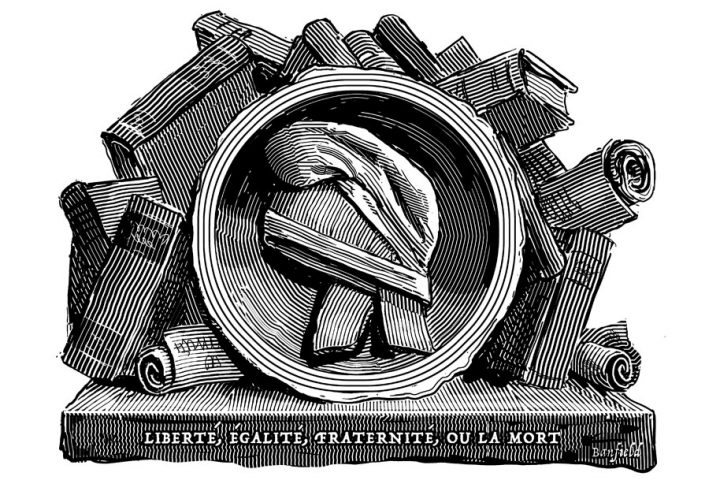

Almost every weekday in school auditoriums, city office buildings, and county courthouses across the land, thousands of recent immigrants—hailing from every nation, belonging to every race and creed, happily waving little American flags—perform their first act as citizens of the United States by perjuring themselves in front of its authorities. “I hereby declare, on oath,” they recite, “that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen.”

Until recent decades, the traditional oath of allegiance was understood in an uncomplicated way: when you became an American citizen you ceased to be the thing you were before. But starting with the Supreme Court’s Afroyim v. Rusk decision in 1967, which found voting in a foreign election to be consistent with American citizenship, federal authorities ceased to insist that American citizenship be an exclusive thing. A spike in dual citizenship has been the result. It is impossible to say how many Americans have availed themselves of it, but the number of those eligible is in the tens of millions. The oath is still part of the ceremony, yet today you can pass U.S. Customs and show the officer two passports—or even three—and he’ll say nothing about renouncing or abjuring. He’ll just say, “Welcome home.”

Loyalty and Allegiance

Political theorists used to think dual citizenship a dangerous thing because it presents occasions for dual loyalty and erodes the social compact on which all citizens’ rights depend. Under the newer understanding, that’s a feature rather than a bug. We live in an interconnected global economy in which we’re supposed to have multiple loyalties. Rights are human rights—no national authority need assert them.

There will always be a use for dual citizenship, especially in dealing with children of international marriages. But the old understanding was more right than wrong. The transformation from national citizens’ rights to universal human rights does divide loyalties and corrode sovereignties. On top of that, we are beginning to notice practical problems with mass dual citizenship that were hardly considered at all when we began dispensing it liberally at the sunny outset of the civil rights era.

Dual citizenship undermines equal citizenship, producing a regime of constitutional haves and have-nots. The dual citizen has, at certain important moments and in certain important contexts, the right to choose the regime under which he lives. He can avoid military conscription, duck taxes, and flee prosecution. When Spain, as coronavirus cases spiked in mid-March, banned all movement outside the home except for designated purposes, one of those purposes was to “return to your habitual place of residence.” A Spaniard with citizenship in a second country thus had the constitutional privilege of exempting himself from a nationwide lockdown in a way that his fellow Spaniard did not. Such special privileges do not often matter—but when they do, they matter in a life-or-death way.

You would have to be a very provincial person not to see that the problems traditionally associated with loyalty to two countries can become quite severe. A classic articulation of this worry was the Supreme Court dissent by Justice Melville Fuller in United States v. Wong Kim Ark in 1898. That case established so-called “birthright citizenship”—the understanding, controversial in many quarters, that the 14th Amendment grants citizenship for all people born on American soil. “I understand the subjects of the Emperor of China,” Justice Fuller wrote,

to be bound to him by every conception of duty and by every principle of their religion, of which filial piety is the first and greatest commandment; and formerly, perhaps still, their penal laws [imposed] the severest penalties on those who renounced their country and allegiance…. The Fourteenth Amendment was not designed to accord citizenship to persons so situated and to cut off the legislative power from dealing with the subject.

The problem is not that newcomers on American soil are bearing Americans—that’s what we, and our governments, have traditionally wanted them to do. The problem is that they are bearing people with a possibly greater and, as Fuller implied, possibly ineradicable loyalty to something else besides America.

Certainly anxieties about race played a part in the skepticism of Fuller and others about migrants’ loyalties. Against efforts to water down Congress’s Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Senator John P. Jones of Nevada asked: “What encouragement do we find in the history of our dealings with the negro race or in our dealings with the Indian race to induce us to permit another race-struggle in our midst?” But as the University of California, Davis, legal scholar Gabriel Chin has shown, in the wake of the Chinese Exclusion Act, China and the so-called Chinese Six Companies were quite capable of assembling a powerful constituency in the United States, including a team of elite lawyers, to argue on behalf of a more cosmopolitan understanding of citizenship and belonging. Today, judiciaries around the world make strenuous efforts to protect this cosmopolitan understanding of citizenship from having to square off against Fuller’s commonsensical one, which is more popular among voters.

Varieties of Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship was a rare status in the 20th century; generally only a few children of international marriages had it. So, for a while, did former British Empire subjects: Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders, and others transitioning into their post-imperial national identities. But today 60% of countries recognize some kind of split allegiance. The English-speaking countries are still probably the most easygoing. The practice is tightly restricted in Asia: neither China nor India has dual citizenship, and in Japan it exists for children only.

Feminism has been a major driver of its proliferation. With some exceptions, a father’s citizenship used to be the family’s. In Switzerland until 1952, women lost their citizenship automatically upon marrying a foreigner. In Japan things worked similarly until the mid-1980s. Dual citizenship has lately become a bargaining chip in a “race to the bottom” to capture international investment capital. Certain countries, including the United States, sell “golden visas” that permit residence. Cyprus sells citizenship itself, which confers the privilege of traveling visa-free around the European Union. At last report, these citizenships cost €1.5 million apiece, and Cyprus had pocketed €6 billion from them.

Probably the most cosmopolitan citizenship regime in the world right now is Switzerland’s. When the Swiss began gathering statistics on such matters in 1926, dual citizenship was almost unknown. But it has been growing—by 40% in the past decade. In Switzerland as in the United States, most people expect dual citizenship to be an exception. Increasingly it’s not. About a third of Swiss marriages are to foreigners. This creates an especially large cohort of binational offspring, and parental applications for Swiss citizenship often follow the baptism of binational children. But there are also many native Swiss who live abroad, and more than two thirds of them have taken the nationality of another country. On top of that, about a quarter of Switzerland’s population consists of immigrants. Add these together and the so-called Mono-Schweizer—people with only one passport—account for only about half the population.

Naturally, not-wholly-Swiss Swiss have begun to throw their political weight around. In the so-called “Double-Eagle Affair” of 2018, two Kosovo-born players on the Swiss national soccer team taunted their Serbian opponents with Kosovar hand gestures. Such episodes sow resentment—because dual citizenship is an institution that, like many in our society since the civil rights era, systematically favors new arrivals over established incumbents. It marks a return, under 21st-century circumstances, to the status of denizen, a word coined in 15th-century England to describe certain foreigners armed with special privileges. Unsurprisingly, in recent years, the Swiss public has taken a populist turn, voting to ban minarets and giving steady support to the anti-elite Swiss People’s Party.

Almost by definition, dual citizenship serves Swiss elites—those who inhabit the globalized part of the country’s economy. But one would assume they would never be government elites. Someone tasked with protecting the interests of the state should be above the suspicion of ulterior motives, so a dual citizen is no more suited to a top government position than a paid lobbyist would be. But in 2016 the Swiss Bundesrat lifted its one-passport requirement. In countries around the world politicians and even diplomats have strained mightily against the rather commonsensical demand that they confine their national loyalty to their own country. In Australia, serving in Parliament with a second passport is a straightforward, unambiguous violation of section 44(i) of the constitution, and yet dozens of dual citizens have flouted that provision and run for Parliament. In the so-called “parliamentary eligibility crisis” in 2017-18, 15 of them had to resign.

That scandal produced some conspicuously illogical arguments in favor of dual citizenship. “[T]he Australian psyche,” wrote the Canberra legal theorist Kim Rubenstein, “is conditioned to dual citizenship as Australians were for many years both British subjects and Australian citizens.” How so? Historically speaking these are overlapping (and, for many, synonymous) self-conceptions, rather like state and national citizenship in the United States. What needs to be resolved in such cases is the practical problem of which level of citizenship takes precedence. In the U.S. this resolution came with the late 19th-century cases of Chae Chan Ping v. United States (1889) and Fong Yue Ting v. United States (1893), which established the doctrine that Congress, not the states, possesses “plenary power” to make immigration policy.

Today, though, the plenary power doctrine is wobbling. Activist American judges tend to defend plenary power ruthlessly against state laws that would exclude immigrants, and treat the plenary power doctrine as no barrier to state laws that welcome immigrants. So Arizona governor Jan Brewer’s Obama-era reforms, which offered a supplemental state role in enforcing federal law, were ruled out of bounds, and the We Build the Wall group that tried to crowdfund a section of Donald Trump’s border wall in New Mexico has met no end of headaches. But sanctuary cities, with their even more direct defiance of federal statute, have frequently been upheld.

Dual loyalty is not just a bugaboo for bigots. It is a practical problem. You can see that in the futile attempts of the United Kingdom to secure the release of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe from Iran, where she has been jailed since 2016 on charges of conspiring against the government. Almost monthly, her husband demands a meeting with the prime minister (first David Cameron, then Theresa May, now Boris Johnson) and calls for extraordinary diplomatic measures to secure Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s release. The British passport has beautiful archaic language to the effect that “Her Britannic Majesty’s Secretary of State Requests and requires in the Name of Her Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance.” But it turns out to be a big problem that Zaghari-Ratcliffe is a citizen not just of Britain but also of Iran. That stern language cannot be asserted quite so forcefully against an Iranian government that has its own claims to her loyalty, and the British public is commensurately less inclined to rally to her cause.

Community and Inequality

As the world globalized in the years before the coronavirus, dual loyalty appeared to be a problem of diminishing importance. Perhaps it is indeed no longer the main problem with dual citizenship. Inequality before the law may be a more serious matter.

The very strange Supreme Court case out of which our regime of dual citizenship arose in 1967, the above-mentioned Afroyim v. Rusk, concerned whether a dual Israeli-American citizen’s voting in an Israeli election constituted proof that he had another allegiance that might serve as grounds for government action to revoke his U.S. citizenship. The Court said no. The indirect result of Afroyim, especially after Vance v. Terrazas in 1980, is that there is almost nothing a dual citizen can do, short of attempting to join a terrorist group and wage active, armed combat on U.S. territory, that can deprive him of the right to call himself an American.

The legal theorist Peter Spiro of Temple University wrote in a celebrated essay about Afroyim: “It is precisely because citizenship has become less salient that it is now more easily retained, and the fact that it is so easily retained inexorably reduces further its value.” Spiro is not only the leading American authority on multiple citizenship, but also a leading advocate for it. How we judge the salience and the value of citizenship depends on how we define citizenship in the first place. Spiro alludes to Hannah Arendt’s description of citizenship, later picked up on by Chief Justice Earl Warren, as the “right to have rights.” He is not sure we need this kind of citizenship today. We are living, after all, “in the wake of the human rights revolution, under which rights are contingent on personhood rather than nationality.”

But citizenship is about more than rights. If we describe it in an Aristotelian way as “membership in a political community,” then maybe there is a sense in which its value has gone down, because the scope of action that such membership brings has narrowed. If voting is the main action that marks political membership in modern republics, the encroachment of modern administrative power (via bureaucracies and judicial decrees) on voter sovereignty may indeed have reduced citizenship’s value.

But if the citizen-state relationship rests on another aspect of community—community as a source of protection—then the decline in citizenship’s value is temporary, maybe even illusory. Come war or criminal prosecution or confiscatory taxation or (as we now see) pestilence, the legal attachment to a particular state can be everything. There was a notorious case in the Maryland suburbs in 1997 when two high-school kids, Samuel Sheinbein and Aaron Needle, murdered a classmate, dismembered the body with a circular saw, and hid it in a trash bag in a vacant house. Needle committed suicide when the crime was discovered. Sheinbein was able to flee to Israel, which does not extradite its citizens, and served a prison sentence there. (He would be killed in a shootout with prison guards many years later.) Director Roman Polanski and former Nissan head Carlos Ghosn are two more celebrated fugitives who were able to benefit from a second citizenship in their flight from justice.

Now suppose we describe citizenship in a more Lockean way, as a collection of rights that amount to a kind of property. Here the importance of citizenship has not only not waned, it has increased enormously—because certain states are better capitalized than others. Several years ago, in the course of her book The Birthright Lottery (2009), University of Göttingen law professor Ayelet Shachar showed that a Western citizenship could be given a pecuniary value that was extraordinarily high, much of this value coming in welfare entitlements. As long ago as 1985, political scientists Peter Schuck and Rogers Smith wrote that for immigrants it is “welfare state membership, not citizenship, that increasingly counts.”

This Schuck-Smith view made a big impact on Harvard’s Samuel Huntington, who used it in the first major intellectual attack on modern dual citizenship, which came in his book Who Are We? (2004). Dual loyalty was at the heart of Huntington’s unease (he likened dual citizenship to bigamy). But what was most original about his critique is that it drew on inequality of various kinds: “Dual citizens with residences in Santo Domingo and Boston can vote in both American and Dominican elections,” he noted, “but Americans with residences in New York and Boston cannot vote in both places.”

There also arose what we might call a civic demoralization. Huntington was appalled by the emptiness of the oath-taking ceremony described above. The cynicism of new immigrants’ “falsely swearing that they are renouncing their previous allegiance” would become corrosive, he warned. Huntington, often wrongly classified as a hidebound reactionary, meant this in an ideologically neutral way, sometimes even in what we would call a progressive way. He did not like the idea of “illegal aliens.” He drew attention to old discussions of the concept of “alienage”—the idea that people can live in the United States without enjoying a full set of citizens’ rights and without carrying a full set of citizens’ responsibilities. Alienage used to be obnoxious to American constitutional thinking. Today most Americans take it for granted.

Rights in the Global Economy

The global economy, and particularly the global labor market, has interacted in a curious way with civil rights as it has developed since the 1960s. All Western societies have this problem in one form or another, but in almost all cases it has evolved out of the American model of globalization. The picture seems contradictory at first: On one hand, the American civil rights regime provides certain classes of citizens with extra rights as citizens (if only to rectify historic injustices), which they can bring to the bargaining table with employers, college admissions officials, and others. On the other hand, you have a workforce of tens of millions arriving in Western countries from what used to be called the Third World, who have fewer rights as citizens. Indeed, they lack many of the basic labor and legal protections that natives enjoy. This is the alienage Huntington spoke of, and alienage may be what creates the employer demand that encourages immigration in the first place.

It puts the American middle class in the position of robbing Peter to pay Paul—Peter being illegal immigrants, and Paul being the native beneficiaries of the civil rights laws. It also creates a generational whiplash. Newcomers are attractive to employers because they have fewer rights than natives. But their American-born children, whether because they are (in most cases) “people of color” or from the mere fact of their immigrant origin (which entitles them to civil rights protections) will be beneficiaries of more rights than natives. Immigration involves inviting sub-citizens who in time will turn into (or whose offspring will turn into) super-citizens. They will be super-citizens in part because they are dual citizens.

Dual citizenship is a great convenience for certain favored people and those who serve them. But it shakes loose the wider society’s understanding of itself as a people—and thus shakes loose the basis on which it can secure its own rights. Citizenship rights are not just an abstract but a practical thing. They have to be not just dreamed up and proposed, but also administered and defended. They are most likely to produce a stable and just society when the people who are asserting them are the same people who are defending them.