Books Reviewed

This essay is adapted from a lecture presented at the Heritage Foundation in Washington, D.C., as part of the Lehrman Lectures on Restoring America’s National Identity.

About a decade ago, when he was vice president, Al Gore explained that our national motto, e pluribus unum, means “from one, many.” This was a sad day for knowledge of Latin among our political elite—and after all those expensive private schools that Gore had been packed off to by his paterfamilias. It was the kind of flagrant mistranslation that, had it been committed by a Republican, say George W. Bush or Dan Quayle, would have been a gaffe heard round the world. But the media didn’t play up the slip, perhaps because they had seen Gore’s Harvard grades and figured he’d suffered enough, perhaps because they admired the remark’s impudence. Though literally a mistake, politically the comment expressed and honored the multicultural imperative, then so prominent in the minds of American liberals: “from one,” or to exaggerate slightly, “instead of one culture, many.” As such it was a rather candid example of the literary method known as deconstruction: torture a text until it confesses the exact opposite of what it says in plain English or, in this case, Latin.

After 9/11, we haven’t heard much from multiculturalism. In wartime, politics tends to assert its sway over culture. In its most elementary sense, politics implies friends and enemies, us and them. The attackers on 9/11 were not interested in our internal diversity. They didn’t murder the innocents in the Twin Towers or the Pentagon or on board the airplanes because they were black, white, Asian-American, or Mexican-American, but because they were American. (Although I bet that for every Jew they expected to kill, the terrorists felt an extra thrill of murderous anticipation.)

In our horror and anguish at those enormities and then in our resolution to avenge them, the American people closed ranks. National pride swelled and national identity—perhaps the simplest marker is the display of the flag—reasserted itself. After 9/11 everyone, presumably even Mr. Gore, understood that e pluribus unum means: out of many, one. Yet the patriotism of indignation and fear can only go so far. When the threat recedes, when the malefactor has been punished, the sentiment cools. Unless we know what about our national identity ought to command admiration and love, we are left at our enemies’ mercy. We pay them the supreme and undeserved compliment of letting them define us, even if indirectly. Unsure of our national identity, we are left uncertain of our national interests, too; now even the war brought on by 9/11 seems strangely indefinite. And so Samuel P. Huntington is correct in his recent book to ask Who Are We? and to investigate what he calls in the subtitle The Challenges to America’s National Identity. What shape will our national identity be in when the present war is over—or when it fades from consciousness, as arguably it has already begun to do?

Creed versus Culture

In Huntington’s view, America is undergoing an identity crisis, in which the long-term trend points squarely towards national disintegration. A University Professor at Harvard (the school’s highest academic honor), he has written a dozen or so books including several that are rightly regarded as classics of modern social science. He is a scholar of political culture, especially of the interplay between ideas and institutions; but in this book he calls himself not only a scholar but a patriot (without any ironic quotation marks). That alone marks him as an extraordinary figure in today’s academy.

Though not inevitable, the disorder that he discerns is fueled by at least three developments in the culture. The first is multiculturalism, which saps and undermines serious efforts at civic education. The second is “transnationalism,” which features self-proclaimed citizens of the world—leftist intellectuals like Martha Nussbaum and Amy Guttman, as well as the Davos set of multinational executives, NGOs, and global bureaucrats—who affect a point of view that is above this nation or any nation. Third is what Huntington terms the “Hispanization of America,” due to the dominance among recent immigrants of a single non-English language which threatens to turn America, in his words, into “a bilingual, bicultural society,” not unlike Canada. This threat is worsened by the nearness of the lands from which these Spanish-speaking immigrants come, which reinforces their original nationality.

Standing athwart these trends are the historic sources of American national identity, which Huntington describes as race, ethnicity, ideology, and culture. Race and ethnicity have, of course, largely been discarded in the past half century, a development he welcomes. By ideology he means the principles of the Declaration of Independence, namely, individual rights and government by consent, which he calls the American “creed” (a term popularized by Gunnar Myrdal). These principles are universal in the sense that they are meant to be, in Abraham Lincoln’s words, “applicable to all men at all times.” Culture is harder to define, but Huntington emphasizes language and religion, along with (a distant third) some inherited English notions of liberty. Who Are We? is at bottom a defense of this culture, which he calls Anglo-Protestantism, as the dominant strain of national identity. Although he never eschews the creed, he regards it fundamentally as the offshoot of a particular cultural moment: “The Creed…was the product of the distinct Anglo-Protestant culture of the founding settlers of America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.”

Twenty-some years ago, he took virtually the opposite position, as James Ceaser noted in a perceptive review in The Weekly Standard. In American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony (1981), Huntington declared, “The political ideas of the American creed have been the basis of national identity.” But the result, even according to his earlier analysis, was a very unstable identity. The inevitable gap between ideals and institutions doomed the country to anguished cycles of moral overheating (“creedal passion periods”) and cooling. He wrote the earlier book as a kind of reflection on the politics of the 1960s and 1970s, noting how the excessive moralism of those times had given way to hypocrisy, complacency, and finally cynicism. In a way, then, the two books really are united in their concern about creedal over-reliance or disharmony.

To bring coherence and stability to American national identity apparently requires a creed with two feet planted squarely on the ground of Anglo-Protestant culture. The creed alone is too weak to hold society together. As he argues in the new book, “America with only the creed as a basis for unity would soon evolve into a loose confederation of ethnic, racial, cultural and political groups.” It is not excessive individualism he worries about; he fears rather that individuals, steering by the creed alone, would soon be attracted to balkanizing group-identities. Therefore, the creed must be subsumed under the culture, if creed and country both are to survive; indeed, “if they are to be worthy of survival, because much of what is most admirable about America” is in its culture, at its best.

Anglo-Protestantism

Huntington’s argument provides a convenient starting point for thinking about the problem of American national identity, which touches immigration, bilingual education, religion in the public square, civic education, foreign policy, and many other issues. While agreeing with much of what he says about the culture’s importance, I want to speak up for the creed and for a third point of view, distinct from and encompassing both.

Huntington outlines two sources of national identity, a set of universal principles that (he argues) cannot serve to define a particular society; and a culture that can, but that is under withering attack from within and without. His account of culture is peculiar, narrowly focused on the English language and Anglo-Protestant religious traits, among which he counts “Christianity; religious commitment;…and dissenting Protestant values of individualism, the work ethic, and the belief that humans have the ability and the duty to try to create heaven on earth, a ‘city on a hill.'” Leave aside the fact that John Winthrop hardly thought that he and his fellow Puritans were creating “heaven on earth.” Is Huntington calling for the revival of all those regulations that sustained Winthrop’s merely earthly city, including the strictures memorably detailed in The Scarlet Letter? Obviously not, but when fishing in the murky waters of Anglo-Protestant values, it is hard to tell what antediluvian monsters might emerge. If his object is to revive, or to call for the revival of, this culture, how will he distinguish its worthy from its unworthy parts?

Huntington is on more solid ground when he impresses “English concepts of the rule of law, the responsibility of rulers, and the rights of individuals” into the service of our Anglo-Protestantism. Nonetheless, he is left awkwardly to face the fact that his beloved country began, almost with its first breath, by renouncing and abominating certain salient features of English politics and English Protestantism, including king, lords, commons, parliamentary supremacy, primogeniture and entail, and the established national church. There were, of course, significant cultural continuities: Americans continued to speak English, to drink tea (into which a little whiskey may have been poured), to hold jury trials before robed judges, to read (most of us) the King James Bible, and so forth. But there has to be something wrong with an analysis of our national culture that literally leaves out the word “American.” Anglo-Protestantism—what’s American about that, after all? The term would seem to embrace many things that our countrymen have tried and given up—or that have never been American at all, much less distinctively so.

Huntington tries to get around this difficulty by admitting that the American creed has modified Anglo-Protestantism. But if that is so, how can the creed be derived from Anglo-Protestantism? When, where, how, and why does that crucial term “American” creep onto the stage and into our souls? He allows that “the sources of the creed include the Enlightenment ideas that became popular among some American elites in the mid-eighteenth century.” But he suggests that these ideas did not change the prevailing culture so much as the culture changed them. In general, Huntington tries to reduce reason to an epiphenomenon of culture, whether of the Anglo-Protestant or Enlightenment variety. He doesn’t see—or at any rate, he doesn’t admit the implications of seeing—that reason has, or can have, an integrity of its own, independent of culture. But Euclid, Shakespeare, or Bach, for example, though each had a cultural setting, was not simply produced by his culture, and the meaning of his works is certainly not dependent on it or limited to it. It is the same with the most thoughtful American Founders and with human equality, liberty, and the other great ideas of the American creed.

The Cultural Approach

Huntington’s analysis is closer than he might like to admit to the form of traditionalist conservatism that emerged in Europe in opposition to the French Revolution. These conservatives, often inspired by Edmund Burke but going far beyond him, condemned reason or “rationalism” on the grounds that its universal principles destroyed the conditions of political health in particular societies. They held that political health consisted essentially in tending to a society’s own traditions and idiosyncrasies, to its peculiar genius or culture. As opposed to the French Revolution’s attempt to make or construct new governments as part of a worldwide civilization based on the rights of man, these conservatives argued that government must be a native growth, must emerge from the spontaneous evolution of the nation itself. Government was a part of the Volksgeist, “the spirit of the people.” Politics, including morality, was in the decisive respect an outgrowth of culture.

But on these premises, how can one distinguish good from bad culture? What began as the rejection of rationalism quickly led to the embrace of irrationalism. Or to put it differently, the romance soon drained out of Romanticism once the nihilistic implications of its rejection of universals became clear. Huntington is right, of course, to criticize multiculturalism as destructive of civic unity. But he is wrong to think that Anglo-Protestant culture is the antidote, or even merely our antidote, to multiculturalism and transnationalism.

Multiculturalism likes to assert that all cultures are created equal, and that America and the West have sinned a great sin by establishing white, Anglo-Saxon, Christian, heterosexual, patriarchal, capitalist—what’s next, hurricane-summoning?—culture as predominant. The problem with this argument is that it is self-contradictory. For if all cultures are created equal, and if none is superior to any other, why not prefer one’s own? Thus Huntington’s preference for Anglo-Protestantism—he never establishes it as more than a patriot’s preference, though as a scholar he tries to show what happens if we neglect it—is to that extent perfectly consistent with the claims of the multiculturalists, the only difference being that he likes the dominant culture, indeed, wants to strengthen it, and they don’t.

Of course, despite their protestations, multiculturalists do not actually believe that all cultures are equally valid. With a clear conscience, they condemn and reject anti-multiculturalism, not to mention cultures that treat women, homosexuals, and the environment in ways that Western liberals cannot abide. Unless, perchance, such treatment is handed out by groups hostile to America; for Robert’s Rules of Multicultural Order allow peremptory objections against, say, the Catholic Church, that are denied against such as the Taliban. Scratch a multiculturalist, then, and you find a liberal willing to condemn all the usual cultural suspects.

Whether from the Right or the Left, the cultural approach to national identity runs into problems. To know whether a culture is good or bad, healthy or unhealthy, liberating or oppressive, one has to be able to look at it from outside or above the culture. Even to know when and where one culture ends and another begins, and especially to know what is worth conserving and what is not within a particular culture, one must have a viewpoint that is not determined by it. For example, is the culture of slavery, or that of anti-slavery, the truer expression of Americanism? Both are parts of our tradition. One needs some “creed,” it turns out, to make sense of culture. I mean creed, not merely in the sense of things believed (sidestepping whether they are true or not), but in the sense of moral principles or genuine moral-political knowledge. If that were impossible, if every point of view were merely relative to a culture, then you’d be caught in an infinite regress. No genuine knowledge, independent of cultural conditioning, would be possible—except, of course, for the very claim that there is no knowledge apart from the cultural, which claim has to be true across all cultures and times. But then genuine knowledge would be possible, after all, and culturalism would have refuted itself.

Hard Sell

One of the oddities of Huntington’s argument is that the recourse to Anglo-Protestantism makes it, from the academic point of view, less objectionable, and from the political viewpoint, less persuasive. As a scholar, he figures that he cannot endorse the American creed or its principles of enlightened patriotism as true and good, because that would be committing a value judgment. So he embeds them in a culture and attempts to prove (and does prove, so far as social science allows) the culture’s usefulness for liberty, prosperity, and national unity, should you happen to value any of those. The Anglo-Protestantism that he celebrates, please note, is not exactly English Protestantism (he wants to avoid the national church), but dissenting Protestantism, and not all of dissenting Protestantism but those parts, and they were substantial, that embraced religious liberty. In short, those parts most receptive to and shaped by the creed.

As a political matter, Anglo-Protestantism is a hard sell, particularly to Catholics, Jews, Mexican-Americans, and many others who don’t exactly see themselves in that picture. Huntington affirms, repeatedly, that his is “an argument for the importance of Anglo-Protestant culture, not for the importance of Anglo-Protestant people.” That is a very creedal, one might even say a very American, way of putting his case for culture, turning it into a set of principles and habits that can be adopted by willing immigrants of whatever nation or race. This downplays much of what is usually meant by culture, however, and it is not clear what he gains by it. If that is all there is to it, why not emphasize the creed or, more precisely, approach the culture through the creed?

The answer, I think, is that Huntington regards the creed by itself as too indifferent to the English language and God. But there is no connection between adherence to the principles of the Declaration and a lukewarm embrace of English for all Americans. In fact, a country based on common principles would logically want a common language in which to express them. The multiculturalists, tellingly, attack English and the Declaration at the same time. As for God, there is no reason to accept the ACLU’s godless version of the creed as the correct one. The Declaration mentions Him four times, for example, and from the Declaration to the Gettysburg Address to the Pledge of Allegiance (a creedal document if there ever was one), the creed has affirmed God’s support for the rational political principles of this nation.

Regime Change

Yet it is precisely these principles that Huntington downplays, along with their distinctive viewpoint. This viewpoint, which goes beyond culture, is the political viewpoint. It is nobly represented by our own founders and its most impressive theoretical articulation is in Aristotle’s Politics. For Aristotle, the highest theme of politics and of political science is founding. Founding means to give a country the law, institutions, offices, and precepts that chiefly make the country what it is, that distinguish it as a republic, aristocracy, monarchy, or so on. This authoritative arrangement of offices and institutions is what Aristotle calls “the regime,” which establishes who rules the country and for what purposes. We hear much about “regime change” today but perhaps don’t reflect enough about what the term implies. The regime is the fundamental fact of political life according to Aristotle. And because the character of the rulers shapes the character of the whole people, the regime largely imparts to the country its very way of life. In its most sweeping sense, regime change thus augurs a fundamental rewiring not only of governmental but of social, economic, and even religious authority in a country. In liberal democracies, to be sure, politics has renounced much of its authority over religion, society, and the economy. But even this renunciation is a political act, a regime decision.

Founding is regime change par excellence, the clearest manifestation of politics’ ability to shape or rule culture. But even Aristotle admits that the regime only “chiefly” determines the character of a country, comparing it to a sculptor’s ability to form a statue out of a block of marble. Much depends as well on the marble, its size, condition, provenance, and so forth. Although the sculptor wishes to impose a form (say, a bust of George Washington) on the marble, he is limited by the matter he has to work with and may have to adapt his plans accordingly. By the limitations or potentialities of the matter Aristotle implies much of what we mean by culture. That is, every founder must start from something—a site, a set of natural resources, a population that already possesses certain customs, beliefs, family structure, economic skills, and maybe laws. Aristotle chooses to regard this “matter” or what we would call culture as the legacy, at least mostly, of past politics, of previous regimes and laws and customs. By in effect subordinating culture to politics, he emphasizes the capacity of men to shape their own destiny or to govern themselves by choosing (again) in politics. He emphasizes, in other words, that men are free, that they are not enslaved to the past or to their own culture. But he does not confuse this with an unqualified or limitless liberty to make ourselves into anything we want to be. We are just free enough to be able to take responsibility for the things in life we cannot choose—the geographical, economic, cultural, and other factors that condition our freedom but don’t abolish it.

Now it is from this viewpoint, the statesman’s viewpoint, that we can see how creed and culture may be combined to shape a national identity and a common good. In fact, this can be illustrated from the American Founding itself. In the 1760s and early 1770s American citizens and statesmen tried out different arguments in criticism of the mother country’s policies on taxation and land rights. Essentially, they appealed to one part of their political tradition to criticize another, invoking a version of the “ancient constitution” (rendered consistent with Lockean natural rights) to criticize the new one of parliamentary supremacy, in effect appealing not only to Lord Coke against Locke, but to Locke against Locke. In the Declaration of Independence, the Americans appealed both to natural law and rights on the one hand, and to British constitutionalism on the other, but to the latter only insofar as it did not contradict the former. Thus the American creed emerged from within, but also against, the predominant culture. The Revolution justified itself ultimately by an appeal to human nature, not to culture, and in the name of human nature and the American people, the Revolutionaries set out to form an American Union with its own culture.

Immigration and Education

They understood, that is, that the American republic needed a culture to help uphold its creed. The formal political theory of the creed was a version of social contract theory, amended to include a central role for Founding Fathers. In John Locke’s Second Treatise, the classic statement of the contract theory, there is little role for Founding Fathers, really, inasmuch as they might represent a confusion of political power and paternal power, two things that Locke is at great pains to separate. He wants to make clear that political power, which arises from consent, has nothing to do with the power of fathers over their children. And so, against the arguments of absolutist patriarchal monarchy, he attempted clearly to distinguish paternal power from contractual or political power. But in the American case we have combined these, to an extent, almost from the beginning. The fathers of the republic are our demi-gods, as Thomas Jefferson, of all people, called them. They are our heroes, who establish the sacred space of American politics, and citizens (and those who would be) are expected to share a general reverence for them and their constitutional handiwork.

In fact, the American creed, together with its attendant culture, illuminates at least two issues highly relevant to national identity, namely, immigration and education. On immigration, the founders taught that civil society is based on a contract, a contract presupposing the unanimous consent of the individuals who come together to make a people. When newcomers appear, they may join that society if they and the society concur. In other words, from the nature of the people as arising from a voluntary contract, consent remains a two-way street: an immigrant must consent to come, and the society must consent to receive him. Otherwise, there is a violation of the voluntary basis of civil society. The universal rights of human nature translate via the social compact into a particular society, an “us” distinct from “them,” distinct even from any other civil society constituted by a social contract.

Any individual has, in Jefferson’s words, the right to emigrate from a society in which chance, not choice, has placed him. But no society has a standing natural duty to receive him or to take him in. Thus it is no violation of human rights to pick and choose immigrants based on what a particular civil society needs. In America’s case, the founders disagreed among themselves about whether, say, farmers or manufacturers should be favored as immigrants, but they agreed, as Thomas G. West and Edward J. Erler have shown, that the country needed newcomers who knew English, had a strong work ethic, and possessed republican sentiments and habits.

For its first century or so, the United States had naturalization laws but no immigration laws, so that, technically speaking, we had open borders. Effectively, however, the frontiers were not so open: most immigrants had to cross several thousand miles of perilous ocean to reach us. Nonetheless, American statesmen wanted to influence as much as they could who was coming and why. Benjamin Franklin, for instance, wrote a famous essay in 1784 called “Information to Those Who Would Remove to America,” in which he cautioned his European readers that America was the “Land of Labor”: if they were planning to emigrate they had better be prepared to work hard. America was not the kind of country, he wrote, where “the Fowls fly about ready roasted, crying, Come eat me!”

As for education, from the creedal or contractual point of view, each generation of citizens’ children might be considered a new society. But Jefferson’s suggestion that therefore all contracts, laws, and constitutions should expire every generation (19 years, he calculated) was never acted on by him, much less by any other founder. Instead of continual interruptions (or perhaps a finale) to national identity, succeeding generations, so the founders concluded, were their “posterity,” for whom the blessings of liberty had to be secured and transmitted. Perpetuating the republic thus entailed a duty to educate the rising generation in the proper creed and culture.

If certain qualities of mind and heart were required of American citizens, as everyone agreed, then politics had to help shape, directly and indirectly, a favoring culture. Most of the direct character formation, of course, took place at the level of families, churches, and state and local governments, including private and (in time) public schools. In the decades that followed the founding, the relation between the culture and creed fluctuated in accordance with shifting views about the requirements of American republicanism. Unable to forget the terrors of the French Revolution, Federalists and Whigs tried to stimulate root growth by emphasizing the creed’s connection to Pilgrim self-discipline and British legal culture. This was, perhaps, the closest that America ever came to an actual politics of Burkeanism. Although the American Whigs never abandoned the creed’s natural-rights morality, they adorned it with the imposing drapery of reverence for cultural tradition and the rule of law. In many respects, in fact, Huntington’s project is a recrudescence of Whiggism.

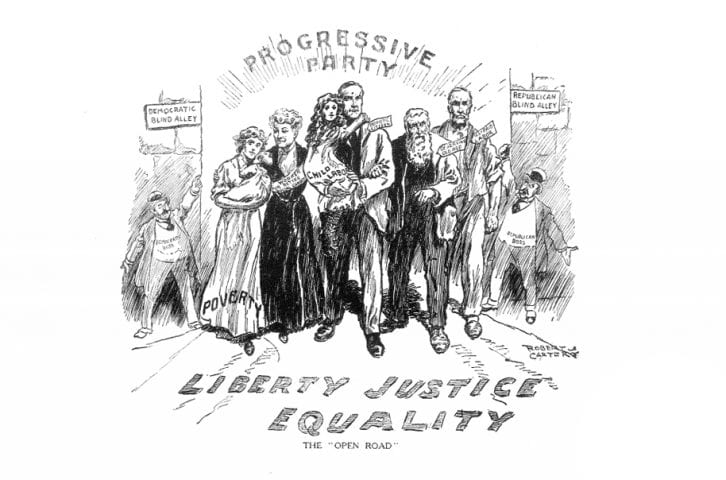

By contrast, Jeffersonian Republicans, soon turned Jacksonian Democrats, preferred to dignify the creed by enmeshing it in a historical and progressive account of culture. They, too, were aware of the problem of Bonapartism, which had seized and destroyed French republicanism in its infancy; and in Andrew Jackson, of course, they had a kind of Bonaparte figure in American politics whom they were happy to exploit. But in their own populist manner they responded to the inherent dangers of Bonapartism by embracing a kind of theory of progress, influenced by Hegel though vastly more democratic than his, which recognized the People as the vehicle of the world-spirit and as the voice of God on earth. (You can find this in the essays and books of George Bancroft, the Jacksonian-era historian and advisor to Democratic presidents, as well as in popular editorials in the North American Review and elsewhere.) The people were always primary, in other words. Jackson and even the founders were their servants; every great man the representative of a great people. Here too the creed tended to merge into culture, though in this case into forward-looking popular culture.

In his early life, Abraham Lincoln was a Whig, memorably and subtly warning against the spirit of Caesarism and encouraging reverence for the law as our political religion. But Lincoln’s greatness depended upon transcending Whiggism for the sake of a new republicanism, a strategy already visible in his singular handling of the stock Whig themes as a young man. In fact, his new party called itself the Republican Party as a kind of boast that the new republicanism intended to revive the old. Their point was that the former Democratic Republicans, now mere Democrats, had abandoned the republic, which Lincoln and his party vowed to save. Rejecting Whiggish traditionalism as well as Democratic populism and progressivism, Lincoln rehabilitated the American creed, returning to the Declaration and its truths to set the face of American law against secession and slavery, to purge slavery from the national identity, and to reassert republican mores in American life and culture. This last goal entailed the American people’s long struggle against Jim Crow and segregated schools, as well as our contemporary struggle against group rights and racial and sexual entitlements.

Lincoln and his party stood for a reshaping of American culture around the American creed—”a new birth of freedom.” Because the creed itself dictated a limited government, this rebirth was not an illiberal, top-down politicization of culture of the sort that liberal courts in recent decades have attempted. Disciplined by the ideas of natural rights and the consent of the governed, this revitalization was a persuasive effort that took generations, and included legislative victories like the Civil War Amendments and the subsequent civil rights acts. Government sometimes had to take energetic action to secure rights, to be sure, e.g., to suppress the culture of lynching. Nor should we forget that peaceful reforms presupposed wartime victory. As with the Revolution, it took war to decide what kind of national identity America would possess—if any. But war is meaningless without the statecraft that turns it so far as possible to noble ends, and that prepares the way for the return of truly civil government and civil society.

We Hold These Truths

Modern liberalism, beginning in the Progressive era, has done its best to strip natural rights and the Constitution out of the American creed. By emptying it of its proper moral content, thinkers and politicians like Woodrow Wilson prepared the creed to be filled by subsequent generations, who could pour their contemporary values into it and thus keep it in tune with the times. The “living constitution,” as the new view of things came to be called, transformed the creed, once based on timeless or universal principles, into an evolving doctrine; turned it, in effect, into culture, which could be adjusted and reinterpreted in accordance with history’s imperatives. Alternatively, one could say that 20th-century liberals turned their open-ended form of culturalism into a new American creed, the multicultural creed, which they have few scruples now about imposing on republican America, diversity be damned.

To his credit, Huntington abhors this development. Unfortunately, his Anglo-Protestant culturalism, like any merely cultural conservatism, is no match for its liberal opponents. He persists in thinking of liberals as devotees of the old American creed who push its universal principles too far, who rely on reason to the exclusion of a strong national culture. When they abjured individualism and natural rights decades ago, however, liberals broke with that creed, and did so proudly. When they abandoned nature as the ground of right, liberals broke as well with reason, understood as a natural capacity for seeking truth, in favor of reason as a servant of culture, history, fate, power, and finally nothingness. In short, Huntington fails to grasp that latter-day liberals attack American culture because they reject the American creed, around which that culture has formed and developed from the very beginning.

In thinking through the crisis of American national identity, we should keep in mind the opening words of the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths….” Usually, and correctly, we emphasize the truths that are to be held, but we must not forget the “We” who holds them. The American creed is the keystone of American national identity; but it requires a culture to sustain it. The republican task is to recognize the creed’s primacy, the culture’s indispensability, and the challenge, which political wisdom alone can answer, to shape a people that can live up to its principles.