Books Reviewed

A review of Miracle Cure: How to Solve America's Health Care Crisis and Why Canada Isn't the Answer, by Sally Pipes

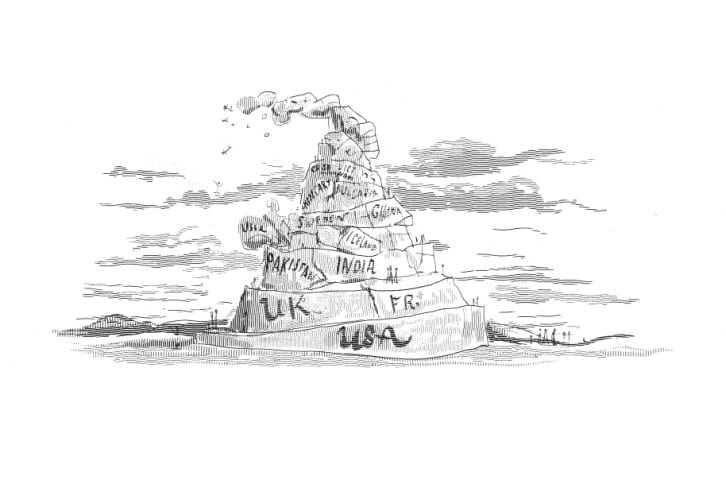

It's 1994 again. In the New York Times, economist-turned-pundit Paul Krugman recently wrote that "[w]ith the cost of health care exploding and the number of uninsured growing, the time will soon be ripe for another try at universal coverage." And he's not the only one interested in revisiting the policy debates of the last decade. Legislatures in California, Ohio, and Vermont are heatedly debating Canadian-style health care. In 15 other states, bills have been introduced calling for the creation of a government-funded insurance scheme.

Many lawmakers who reject a full-bore, HillaryCare-style program (including Senator Clinton herself) remain favorable to a massive government effort with an elaborate mix of initiatives. A bipartisan coalition in Congress is clamoring for drug re-importation to tame prescription medication prices, reinsurance by the federal government to tackle rising insurance costs, and other nostrums. So what now for American health care—and is there an alternative to government creep? In her eloquent new book, Sally Pipes, president of the San Francisco-based Pacific Research Institute, answers these questions.

HillaryCare didn't make sense in the early 1990s, nor does it now. Pipes, who was born and raised in Canada, takes a hard look at the "miracle cure"—a Canadian-style system that seems to offer it all: both modern medicine and universal coverage. What she describes, however, is a system in disarray. No wonder. With health care free at the point of use, demand surged and costs spiraled. To address the inherent economic problem, government planners quickly began restricting the supply of health care—cutting medical school graduates, placing caps on the number of diagnostic tests performed in a year, closing hospitals.

Miracle Cure employs both anecdote and statistic to explain the cruel result. Today, Canadians must wait for practically any diagnostic test or surgical procedure; machinery is dated; physician shortages rampant. The most damning assessment of the system comes from a Canadian-born American surgeon who observes: "Canada offers the best health care the 1970s have to offer."

Pipes is not alone in her criticism of Canadian health care. Shortly after the publication of her book, the Supreme Court of Canada called the country's health care system dangerous and deadly, and struck down key laws. Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin and Justice John Major stated: "The evidence in this case shows that delays in the public health-care system are widespread, and that, in some serious cases, patients die as a result of waiting lists for public health care" (emphasis added). If Canada is not the solution, then what is?

* * *

On this, we can all agree: American health care is riddled with problems, including rising insurance costs and expensive public programs. The source of the problem, however, is not what many people assume. Most think that American health care has been overrun by market forces. But "government," as Pipes astutely observes, "has been the largest single payer in the U.S. health care marketplace since the 1960s." Perhaps more importantly, government actions (including revisions to the tax code made during World War II) have meant that American health care is unlike any other sector of the economy because consumers (patients) don't pay directly for much of the service they receive.

In fact, American consumers pay just 14 cents of every health dollar spent. As a result, the very concept of insurance has been distorted:

Homeowners' insurance covers fires, trees collapsing on the roof, and other similarly large events. Automobile insurance covers major dents, broken glass, and total wrecks. But what travels under the name of health insurance in the United States has expanded to cover just about everything, including the routine, the predictable and the easily affordable. It's as if automobile insurance paid for the 3,000 mile oil change and the 30,000 mile tune up, or if homeowners' insurance paid to replace burnt out light bulbs and leaky faucets.

The economics are clear. Consumers pay little directly—and demand expensive, inefficient service. With a third party paying the bills, key decisions are left to payers, not patients. It's a prescription for universal dissatisfaction.

The same market forces that have transformed other sectors of the economy haven't shaped health care. Take hospital pricing. Since January 2005, California has required that all hospitals provide basic pricing information. The variation is amazing: a chest X-ray costs $120 at San Francisco General but $1,519 at Doctors Hospital in Modesto; a complete blood count is $47 at Scripps Memorial in Los Angeles, but $547.30 at Doctors in Modesto. Even blood-sucking live leeches range in price from $19 per leech at Scripps to $81 per leech at the U.C. Davis hospital. (These figures were compiled by the Wall Street Journal.) Is there any other industry in America with such vast pricing differences?

Pipes sees an alternative in the concept of consumer-directed health care. Rather than leave important decisions up to others, she wants to "put consumers in the driver's seat." She is particularly enthusiastic about health savings accounts (HSAs), created in 2003 as part of the Medicare Modernization Act. HSAs marry real insurance (that is, coverage for high and unpredictable costs) with contributions to a savings account that can be used to pay for smaller health expenses and "rolled over" from year to year. This puts the consumer, not government, in charge.

The early data on health savings accounts is encouraging. Pipes mentions, for instance, that companies like Whole Foods have used the concept to hold the line on health inflation. Perhaps more interestingly, consumer-driven plans have begun slowly to change the way Americans interact with their health care system. At the Cigna website, for example, members can estimate annual costs, compare drug prices, and get comparisons of hospitals (showing quality ratings for certain procedures as well as the cost and length of stay). Other companies offer "health coaches," professionals who help patients navigate the choppy waters of health care. Non-insurance companies are also getting involved. Websites like DestinationRx.com and PharmacyChecker.com let patients search for their medication and compare prices at different online pharmacies.

While the topics are complex, Pipes explains the nuances of both systems with skill and grace. Miracle Cure is an easy read, and an excellent and important addition to the public policy debate. The question, of course, remains: will American medicine really be transformed or will it simply slide towards greater and greater government control? After six decades of government creep, Sally Pipes's book indicates that the battle is joined.