When Mao Zedong died in 1976, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) mutated from a totalitarian regime into a limited dictatorship under the rule, consecutively, of Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao. Deng foreswore the cult of personality. All three leaders resolved never to return to the days when any man could hold as much power as Mao. Slogans of “spiritual civilization” and “peaceful rise,” and promises of order with harmony, displaced the blood-soaked language of old.

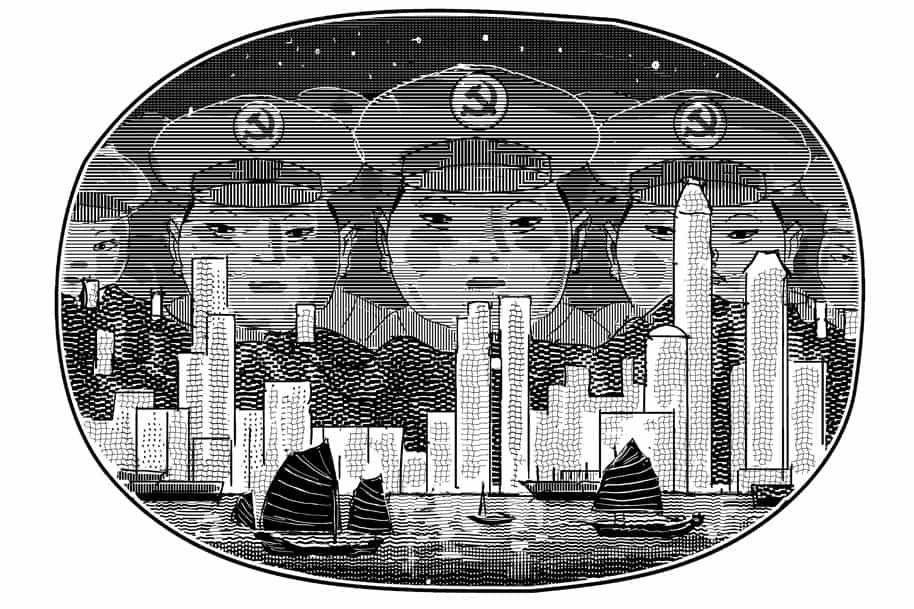

Much has changed under President Xi Jinping. Not since Mao has the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) been as internally repressive and internationally belligerent as it is today. It has never been as wealthy and technologically capable of controlling its people. Forbidding rival sources of allegiance, the CCP locks up clerics and razes churches, temples, and mosques. Demanding total submission, it considers forced sterilization and mass internment to be acceptable methods of pacification. Even the compliant majority of China’s population finds its communications monitored, movements mapped, behaviors graded and recorded. That, of course, induces extreme caution—and further compliance.

Millions rallied in Hong Kong during the summer and fall of 2019 against Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor—a CCP client. Hongkongers fought to preserve their cultural and legal heritage, to defend their liberties, and to democratize their polity against a city government kowtowing to Beijing. The protest’s human cost was staggering. Between June 2019 and early January 2020, Hong Kong police arrested almost 7,000 protesters (over a third were women). Around 2,000 were aged between 11 and 19; 2,500 were students. By mid-August 2020, 22% had been prosecuted; another 1,630 still await trial. Behind these data lie scarred bodies, disturbed minds, dashed hopes, divided families, wrecked careers, cold fear, and boiling rage. It will be years before a full accounting is possible. It may never be.

Two books, each with photographs, describe how the protests began, accelerated, and stalled. Antony Dapiran’s City on Fire is a fast-paced chronicle of the turmoil that gripped Hong Kong between June and late November 2019. A Hong Kong-based lawyer and author, Dapiran witnessed much that he depicts. Though a pro-democracy partisan, he frankly acknowledges the movement’s violence, hyperbole, and paranoia. Rebel City extends the narrative into early spring 2020. Edited by Zuraidah Ibrahim and Jeffie Lam, the book is a collection of articles from the South China Morning Post, Hong Kong’s premier English-language newspaper, where the two work. Snapshots of events are punctuated by profiles of actors, onlookers, and casualties. Fact-based reporting by 32 Post journalists is sharply distinguished from editorializing commentary, which receives its own section.

City on Fire and Rebel City can be read with profit by anyone curious about Hong Kong affairs. But there is another reason why these books merit attention. When their authors relate what Hongkongers affirm, it is impossible not to notice what Westerners are giving up. Hong Kong people do not denounce their city’s history; they are ardent to preserve its memorialization. Nor do Hong Kong people romanticize Marxism as a philosophy of liberation. They are more likely to condemn it as a doctrine of servitude. A principled defense of freedom of conscience, open enquiry, and uncensored speech and writing are all widely accepted in Hong Kong—even by university professors. Could it be that an ex-British colony, on the eastern Pearl River delta, is among the last places on earth to cherish values that Westerners now routinely denigrate?

A New Law

The crisis of 2019 was triggered, as political crises often are, by a response to a murder. In early 2018, a young Hong Kong couple with marriage plans took a vacation to Taipei, Taiwan’s capital city. One evening there, the man went berserk when his fiancée first admitted that he was not the father of the child she was carrying and then taunted him with graphic images of her having sex with another man. A violent struggle ensued; the man choked the woman to death. Returning to Hong Kong, he was questioned by police and admitted his deed. As the murder was committed in Taiwan—with which Hong Kong has no extradition treaty—the legal situation was anomalous. After harrowing appeals for justice from the dead woman’s parents, Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, devised a plan both comforting to the heartbroken parents and pleasing to Hong Kong’s master in Beijing.

Lam’s government contrived a bill to detain and transfer criminal suspects to states with which Hong Kong had no formal extradition treaty. These states included not just Taiwan but mainland China—from which Hong Kong’s legal system was officially separated under the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s sub-constitution. Enshrining a compromise reached by the departing British colonial administration and the incoming Chinese state, the Basic Law seeks to reassure Hongkongers that their accustomed way of life—civil liberties, a capitalist economy, a partly democratic polity, and a common law regime—would be respected until at least 2047 (50 years after China’s resumption of sovereignty over Hong Kong).

Hongkongers were terrified by Carrie Lam’s extradition bill, even as her government, under criticism, pared down the offences for which extradition would be lawful. What foreign newspapers call China’s “opaque legal system” is legal hell for those consigned to its circles. On the mainland it is common for citizens targeted by the party for political offenses—frank-speaking academics and human rights lawyers, for instance—to be charged for non-political ones: corruption, money laundering, tax avoidance, and consorting with prostitutes. Besides, Beijing was already riding roughshod over Hong Kong’s integrity. In 2015, mainland security agents kidnapped Hong Kong vendors and publishers of books deemed scandalous. In 2017, Xiao Jianhua, a mainland financier and business billionaire, alleged to have dirt on China’s leaders, disappeared from his Four Seasons suite in Hong Kong. He languishes in a Chinese prison somewhere awaiting trial for bribery and the manipulation of stock prices. Without even entering a court room, Xiao is doomed.

As Lam prepared to introduce the extradition bill to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (known as LegCo) in April 2019, protest began to build. Demonstrations and petition campaigns were organized. Lam plowed on. Critics were being alarmist, she said. Anxiety would fade. Her government was stunned by what happened next. On June 9, one million people marched against the bill. On June 12, to prevent the bill’s second reading, protesters attempted to storm the LegCo complex, prompting a tear-gas barrage from police. On June 16 a second march attracted two million people—over a quarter of Hong Kong’s 7.5 million residents. The scale of opposition was unprecedented in Hong Kong. The hapless Lam suspended the bill (four months later, it was formally withdrawn).

It was too late. New demands were on the agenda, including an independent inquiry into police crowd-control behavior and universal suffrage to elect members of LegCo and the chief executive. What had begun as a campaign against an extradition bill was now a full-blown democracy movement.

Weekly marches, work stoppages, class boycotts, airport sit-ins, human chains, flash mob actions, confrontations with police, defacing of the Central Government Liaison Office: all and more, as they unfurled over four months, are vividly described in Dapiran’s City on Fire. The Civil Human Rights Front—an NGO umbrella group with links to democracy affiliates across Hong Kong—coordinated most of the official demonstrations. But, as Dapiran emphasizes, the movement eschewed leaders, and was deliberately decentralized. Fluid, agile, and democratic—decisions on tactics were made, often on the fly, via online forums and messaging applications—protesters moved rapidly from location to location outfoxing the police, at least at first.

Against all expectations, the 2019ers cohered. Recalling divisions that had sundered Hong Kong’s 2014 Umbrella Movement (an earlier push for democratic accountability), protesters coined the slogan: “No Splitting, No Cutting Off, No Snitching.” Front-liners willing to engage in pitched battles with police co-existed with a majority of more peaceful moderates who joined marches and demonstrations. Neither group would break ranks with the other. The compact endured as long as the movement enjoyed a large street presence.

Tragedy, Triumph, and Stasis

As summer turned to fall, violence became more common. Stores associated with mainland businesses, particularly those that openly supported Beijing, were trashed. (An unwritten code forbade looting; this was to be a political protest, not an orgy of theft.) Mass Transit Railway (MTR) stations were firebombed when it became known that the MTR was cooperating with the government to close stations near protest sites and impose a curfew on travel. Police responded with ferocity. Christy Leung and Chris Lau report in Rebel City that, between June 2019 and February 2020, officers fired 16,191 rounds of tear gas; 10,100 rubber bullets; and 1,880 sponge grenades, among other ordnance. Was the force proportionate to the disorder?

The question, reasonable in itself, became moot on the evening of July 21, when passengers alighting a train in the town of Yuen Long were attacked with rattan canes and iron rods by a white-shirted gang of around a hundred men. Those beaten consisted not only of protesters returning from a demonstration on Hong Kong island but also regular commuters. Gang members entered the train, assaulting anyone in range—a pregnant woman included. The episode was captured in video clips and streamed live on Facebook. Despite frantic calls for help, police took 39 minutes to show up in strength; no arrests were made. The optics were disastrous for the authorities. Police tardiness suggested that the agency tasked with upholding the law was colluding with village thugs and Chinese gangsters to suborn it. The force’s credibility hemorrhaged. By late November, support for the police, as measured in polls, had sunk to 27.2%, a record low. Entering working class neighborhoods in pursuit of protesters, riot police found themselves met by a torrent of abuse and a hail of projectiles from the apartments above.

All the same, fair-minded readers will applaud Rebel City’s humanization of an embattled police force. For, in truth, its situation was impossible. Thirty-one thousand-strong, the police shielded an incompetent government that was unwilling to devise any political initiative to defuse the crisis. Lam disappeared from sight for days—sometimes weeks—on end, leaving it to her ministers to mouth platitudes about law and order. Police and their families were harangued on the street. Their children were bullied at school. Many cops were doxxed, and their homes set on fire. The force fell back on what it had left: camaraderie, the steely leadership of a new commissioner of police, Chris Tang Ping-keung, and bellicose encouragement from the Central Government and mainland social media.

The year 2019 culminated in an unlikely mixture of tragedy, triumph, and stasis. The first issued from the occupation, that began on November 17, of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, and the subsequent police siege. The mobile tactics that had served protesters so well were abandoned for a blockade. Riots broke out in neighboring Kowloon, partly in solidarity with those trapped on campus, partly to release police pressure on it. A war of attrition ended with the activists’ defeat and mass arrests.

Police now commanded the street. They were helpless in the voting booth. When, on November 24, Hong Kong held its District Council Elections, the pan-democratic parties triumphed in a landslide, winning 392 seats as against their Beijing-friendly rivals’ 60. Of 18 district councils, the democrats secured 17. The result of these local elections was an unmistakable indictment of the Hong Kong government, and its CCP puppeteer—but the protest movement stalled nonetheless. Exhaustion was setting in. The government refused all protester demands. And then, in late January 2020, came COVID-19. Protesters bluntly called it the “Wuhan Virus” and cheered the U.S. president for doing likewise. (City on Fire was published before the pandemic began and Rebel City barely registers it.)

COVID-19 has taught different lessons in different countries. In America it taught that calls for social distancing are helpless to stop violent congregation when state and city politicians stand down their police force. In Hong Kong it taught that a cornered government can cauterize a protest by restricting its ability to form. By government decree, large gatherings were outlawed in Hong Kong “for reasons of public health.” If a crowd greater than four people began to assemble, the police swooped in to make arrests. Mass protests could not gain traction.

City and Soul

In the summer and fall of 2019, Hongkongers waved British flags (and American ones) to denote liberty, the rule of law, and democracy. The shouts that echoed in street canyons and online forums—“Free Hong Kong!” “Reclaim Hong Kong!”—harked back to an old idea of republican freedom: the city and its soul. “Glory to Hong Kong,” the city’s improvised anthem, echoed “Below the Lion Rock,” the theme song of a much-loved television series of the ’70s. It pays homage to the grit and solidarity of working-class Hongkongers committed to ideals of collective advancement in a place where all could thrive from hard work and loyalty to family. “Side by side we overcome ills, / As the Hong Kong story we write.”

That story, with its engrained civic patriotism, has always embarrassed the CCP. Around 2 million mainland Chinese fled to Hong Kong between 1950 and 1979, seeking security and a more prosperous life in the British colony. The British departed in July 1997 but Hong Kong remained—and it was not Communist China. Hong Kong had a history, a history of pulling with the British, a history of pushing against the British, a history that created a distinctive culture of what natives call Hong Kong “people” or Hongkongers or Hong Kong Chinese.

Befitting a self-constituted people, the core demand of the 2019ers was for full democratic suffrage to elect the chief executive and all seats in LegCo, demands prefigured in the Basic Law. The city could only be free when it was self-determining—when Hongkongers ruled themselves. Authoritarian toleration, whether by Britain or by the PRC, was no longer tolerable. This political stance by protesters refuted the government’s preferred explanation for the tumult. Hong Kong’s troubles, ministers said, issued from social and economic causes. Residents were angry at unaffordable apartments, skyrocketing rents, stagnant wages, and stationary careers. Address these, and the protests would end. It was a classic Marxist feint in which politics is rendered epiphenomenal to economics. But Hong Kong’s social ills never defined the protest. A Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute poll, conducted in August 2019, found that among younger residents 84% were motivated to protest in “pursuit of democracy” while 91% cited distrust of Beijing. Discontent at high rents and inflated property prices garnered 58% of those polled.

Aftermath

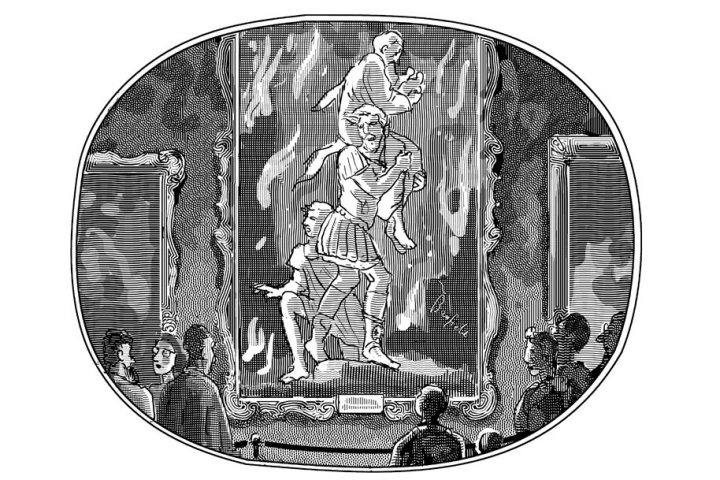

It was the Russian writer Maxim Gorky who said that the only people worthy of freedom are those willing to fight for it every day. Gorky wasn’t; he became an apologist for Stalinism. But the man who, in his novel Cancer Ward (1968), sardonically quotes Gorky’s words was the epitome of such a fighter: Gulag witness Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. In his fiction and lectures, Solzhenitsyn showed what life without freedom—of conscience, of expression, of assembly, of movement, of political representation—looks like. It looks like moral death. And yet, in spite of everything, some of the embattled continue to affirm the virtues of dignity and solidarity.

Gorky manikins, deferential to tyranny, are multiplying in Hong Kong. On June 30, 2020, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress—the PRC’s legislative arm—passed a national security law for Hong Kong outlawing secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with hostile foreign powers. The law is a dragnet to scoop up all who offend the party. Even before its paragraphs were published, five presidents of Hong Kong’s eight publicly funded universities chimed in to support the new law. In July 2020, the University of Hong Kong’s Council (a body of government appointed worthies) fired legal scholar and pro-democracy activist Benny Tai. Around the same time, public libraries in Hong Kong withdrew books written by anyone associated with the democracy movement. Even the South China Morning Post, responsible for the admirable Rebel City, is today sadly diminished. Although it was bought in 2016 by Alibaba Group’s Jack Ma—a Communist Party member—it remained for a time even-handed about Hong Kong’s democracy movement. No longer: since July 2020, the Post’s columns are timid and lackluster. Jimmy Lai’s feisty pro-democracy paper, Apple Daily, survives—for the moment—under considerable official harassment. Lai himself, and several other activists, are already caught in the national security maw.

In 2019 Hongkongers risked life and livelihood for the freedom of their city. Some are now in exile. Others are in prison. Many more await trial and can expect long jail terms. Beyond their names and the crimes for which they will be sentenced, who are these people, really? They are Solzhenitsyn’s heirs on the South China Sea.