The woman's face trembles from what appears to be early-stage Parkinson's disease. Combined with the charged words she speaks to the filmmaker's camera, however, her shaking leaves the impression she is also battling to control her anger and despair:

They have families; have little ones…. Their livelihoods was there. They were making a good wage. And this company comes in and they knocked it all away. They knock their wages down, they take their jobs away, and then eventually they close the plant.

We feel like if he would have wanted to, he was in a position that he could have said, "Hey—these people still got time left." No, that was not the deal. They wanted the machinery; they didn't want us. And that's what they got.

Let's look deeper. Let's look deeper in his life. I think he's a money man…and he's gonna look out for the money people. He didn't look [out] for us little peons, anyway.

"He" is Mitt Romney and "this company" is American Pad and Paper—"AmPad"—in which Bain Capital, the investment firm Romney co-founded and led, once held a controlling interest. In July 1994 it acquired SCM, a manufacturer of hanging folders and writing products with a factory in Marion, Indiana. After the acquisition, according to a New York magazine story on Romney's business career, AmPad

fired all of the union workers [at the Marion plant], more than 250 people in total, then hired most of them back at much lower wages; for years, they had gotten health-care coverage as part of their pay package, but now AmPad asked them to pay half of the costs. The whole plant walked out.

In February 1995 AmPad gave up on solving its labor problems and closed the Marion factory, moving its equipment to facilities in other states.

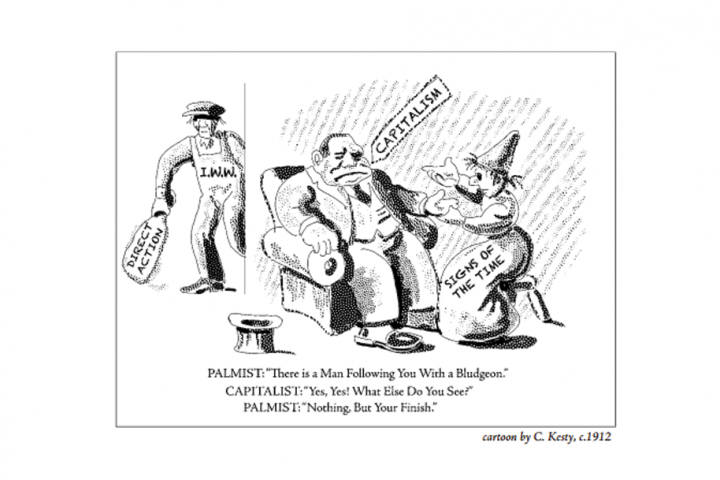

The remarkable thing about When Mitt Romney Came to Town, the documentary featuring the woman from Marion, is its provenance. The 28-minute film is a morality play, contrasting smug, hyper-rich capitalists with salt-of-the-earth Everymen whose hopes have been shattered by economic upheaval. Its portrayal of the suffering in Marion is not, however, Michael Moore's sequel to Roger and Me (1989), his depiction of Flint, Michigan's death spiral. Instead, When Mitt Romney Came to Town is a campaign commercial produced by Winning Our Future, a political action committee supporting Newt Gingrich's presidential campaign. Thus the 1990s' most prominent conservative, whom liberals hated and feared, is now supported by donors who have put up a website deriding "Romney and his cronies" as "predators" who "searched out vulnerable companies, took them over, loaded them with debt, and collected obscene fees while doing so."

Gingrich expressed some misgivings about When Mitt Romney Came to Town, calling on Winning Our Future, which is distinct from his presidential campaign, to "either edit out every single mistake or pull the entire film." Another candidate was less fastidious. Before ending his misbegotten quest for the GOP nomination Governor Rick Perry called Romney a "vulture capitalist," not a "venture capitalist," the difference being that after acquiring troubled companies, Romney and Bain Capital set about "picking their bones clean" rather than working to "clean up those companies, save those jobs." Romney possesses an odd gift for getting other Republican politicians in touch with their inner proletarian: in 2008 when Governor Mike Huckabee was running against Romney he said, "I want to be a president who reminds you of the guy you work with, not the guy who laid you off."

Liberalism after Socialism

During Franklin Roosevelt's first term a worker who still had a job said, "Mr. Roosevelt is the only man we ever had in the White House who would understand that my boss is a son of a bitch." It's not surprising that similar resentments echo in the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. Nonetheless, it's unusual to hear Republicans accusing other Republicans of exploiting the workers.

America has had other recessions, some more severe at least by some measures. Unemployment rose to 10.8% by the end of 1982 as the Federal Reserve, with the support of the Reagan Administration, tightened the money supply—interest rates would climb above 20%—in order to strangle inflation. The Left-to-Right political spectrum remained intact during these downturns, however. Liberals sought greater government intervention into economic activity on behalf of FDR's "forgotten man," while conservatives emphasized the government's capacity to do harm and the unregulated economy's capacity to correct itself. The first sign that old rules had been suspended came in 2009, when the moment of greatest economic peril gave rise to a populist movement on the Right, as the Tea Party strenuously demanded less government, not more. This was the first serious economic downturn since the collapse of Soviet Communism, a denouement that also marked the last gasp of socialism as an economic ideal. The New Deal, by contrast, struggled to end the Great Depression at a time when some serious people still took socialism seriously.

In 1947, for example, the late Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., assured the readers of Partisan Review, "There seems no inherent obstacle to the gradual advance of socialism in the United States through a series of New Deals." (In A Life in the Twentieth Century [2001], Schlesinger described having become an "ardent New Dealer" while a Harvard undergraduate in the 1930s, and remaining "to this day a New Dealer, unreconstructed and unrepentant." Indeed, "I am somewhat embarrassed to confess that I have not radically altered my general outlook in more than half a century.") Schlesinger was confident about America's ability to achieve "democratic socialism"—or "libertarian socialism" or, more disquietingly, "a not undemocratic socialism." The "New Deal greatly enlarged the reserves of trained personnel; the mobilization of industry during [World War II] provided more experience; and the next depression will certainly mean a vast expansion in government ownership and control." Schlesinger voiced contempt for capitalists—even for their ability to protect their own interests—and disappointment in the workers' political will and skill. There was, however, a more promising vehicle for achieving a not undemocratic socialism, the "politician-manager-intellectual type—the New Dealer," provided he is "intelligent and decisive."

By the time Schlesinger died in 2007 it had become impossible to imagine a public intellectual this side of Noam Chomsky enthusing over "a vast expansion in government ownership and control." In 1991 Paul Starr, a Princeton sociologist and co-founder of the American Prospect, wrote an article, "Liberalism After Socialism," advising that magazine's readers, "It is now indisputable that communism impoverished the people who lived under it, and it is not clear how or why a more democratically planned socialist economy would do much better—or that such a system is feasible at all." Repudiating the vision Schlesinger had embraced 44 years earlier, Starr contended that the "synthesis of liberalism and socialism that once excited imaginations now seems almost drained of content." As a result, he urged liberals "to give up on the idea of a grand synthesis or a third way…between capitalism and socialism or an alternative altogether ‘beyond' them."

The task for liberalism after socialism, according to Starr, is, "Reform capitalism, yes; replace it, no." This is, of course, the only possible mission left for the Left, once it concedes that no one has any idea what to replace capitalism with. To re-form capitalism, however, implies that it will be made to con-form to…something, some intelligible standard of a just, efficient economic system. Socialism, despite fatal theoretical and practical flaws, had an elevator pitch. Socialists' efforts would culminate in a centrally directed economy, where the government owned or managed key industries to advance the comprehensive plans it formulated for blending economic growth with social justice.

Liberalism's lack of an elevator pitch makes it impossible to describe the culmination of liberals' efforts. Innumerable books, articles, and seminars have tried and failed to define the central liberal idea that explains and justifies all the individual reforms. None of this rhetoric or theorizing has been able to demonstrate how liberalism after socialism amounts to something bigger and nobler than just messing around. There are worse things for the politician-manager-intellectual type to do than mess around, of course. But no one can find coherence or inspiration in the liberal promise that messing around today will pave the way for more messing around tomorrow.

Stuck with Capitalism

Counterintuitively, America's political history since the fall of the Berlin Wall suggests being incoherent and uninspiring is more of an advantage than a burden for liberalism. In the five presidential elections before November 1989 the Democratic nominee won 43% of all the popular votes, added together, compared to the 54.3% cast for the Republicans. In the five elections since then, the Democrats have won 48.6% of the popular votes, compared to the Republicans' 44.8%.

It was widely and correctly predicted at the time that the collapse of Communism would take away the one issue on which all factions of the conservative movement agreed, however else their concerns were disparate or even irreconcilable. It was also understood that the demise of the Soviet Union would reduce the political salience of national security, an issue that had given Republicans an important advantage over a Democratic party that came to rue but not reject McGovernism. The only Republican presidential nominee who failed to win a popular majority in the five elections from 1972 to 1988 was Gerald Ford. Even he came close, receiving 48% of the vote in 1976 despite bearing the standard of a party whose previous nominee had brought the nation Watergate. The only Republican nominee since the Soviet Union's dissolution to win, barely, a popular majority was George W. Bush in 2004 with 50.7% of the vote. In the first presidential election after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Bush stressed national security over all other concerns, making his argument a throwback to the successful Republican campaigns in the final two decades of the Cold War.

The new political realities since 1989 have also reordered America's domestic policy debates. Capitalism has won, in the sense that every alternative to capitalism has lost. Being the only option left is not the same as being one that's desired, however. The "triumph" of capitalism seems to have done more to increase the number of people resigned to it than the number committed to it.

Furthermore, if the post-socialist liberal prospect of endless messing around does not impress, neither does it alarm. Europe's social democracies have serious problems, which America will do well to avoid—but they don't have gulags. The warning in Friedrich Hayek's The Road to Serfdom (1944) will never become obsolete: a slippery slope leads from government planning to government tyranny. Limiting government defends the space necessary for capitalism, and freedom generally, to flourish.

That contention is not sufficient to secure democratic acceptance of capitalism, however. In a nation that has known democracy for over 200 years the road to serfdom is too long, the existence of detours too plausible, the prospect of tyranny too abstract, for avoiding totalitarianism to be the sole basis for opposing this regulation or that redistribution. The political case for free markets has always relied less heavily on the argument that inhibiting capitalism engenders dictatorship than on the claim that unshackling capitalism engenders prosperity. Freedom Works is the name of one group advocating limited government. At the midpoint of the 1920s President Calvin Coolidge declared that Republican policies of holding down government spending and taxes had bequeathed "peaceful and prosperous industrial relations" in a nation where "employment is plentiful, the rate of pay is high, and wage earners are in a state of contentment seldom before seen."

Coolidge's successor was considerably more emphatic. Upon receiving the Republican presidential nomination in 1928 Herbert Hoover declared:

We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land. The poorhouse is vanishing from among us. We have not yet reached the goal but given a chance to go forward with the policies of the last eight years, we shall soon with the help of God be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation…. This is the primary purpose of the economic policies we advocate. [Emphasis added.]

Ask to be judged for delivering prosperity, and prepare to be condemned when something very different materializes. As Hoover admitted at the start of his doomed 1932 reelection campaign, the nation was enduring "a time of unparalleled economic calamity," bringing "greater suffering and hardship than any which have come to the American people since the aftermath of the Civil War." The GOP has been more and less competitive with the Democrats since 1932, but has never again been the dominant party it was for most of the 64 years separating the Civil War from the Great Depression.

"All of these rights," Franklin Roosevelt said of the "Second Bill of Rights" he put forward in his 1944 State of the Union address, "spell security." Their implementation will realize "new goals of human happiness and well-being." Coolidge, Hoover, and Roosevelt agreed on the basic point that greater economic security is always desirable and increased vulnerability never welcome.

Sturdy Self-Interest

Americans are no different from other peoples in wanting more rather than less, preferring to stand on solid ground than traverse thin ice. The political problem of economic security poses special challenges for the United States, though, given the complex way it intersects with our principles and character. American conservatives believe their entire political mission was laid out in a single year, 1776, which saw the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the publication of The Wealth of Nations. Adam Smith's book, however, is a stern Declaration of Dependence: "In civilized society [man] stands at all times in need of the cooperation and assistance of great multitudes, while his whole life is scarce sufficient to gain the friendship of a few persons…. [Man] has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only."

Smith's famous solution to this dilemma was to render generosity unnecessary by relying on the stronger, steadier force of self-interest: it is "by treaty, by barter, and by purchase, that we obtain from one another the greater part of those mutual good offices which we stand in need of." We make these exchanges thinking all the while of how they will benefitus. A man bothers to examine how an exchange will help the other parties to it, not because he cares about that outcome for itself, but because it helps him devise ways to "show them that it is for their own advantage to do for him what he requires of them." Thus, "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages."

This constant need to induce others to act in ways that advance our interests does more to promote economic vitality than it does to secure psychological or political stability. "It is the manners and spirit of a people which preserve a republic in vigor," Thomas Jefferson wrote in Notes on the State of Virginia, first published in 1785. For this reason he hoped the ever more elaborate division of labor that Adam Smith had delineated would be held in abeyance by the American continent's "immensity of land courting the industry of the husbandman." Jefferson believed that, "Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people" because:

Corruption of morals in the mass of cultivators is a phenomenon of which no age nor nation has furnished an example. It is the mark set on those, who not looking up to heaven, to their own soil and industry, as does the husbandman, for their subsistence, depend for it on the casualties and caprice of customers. Dependence begets subservience and venality, suffocates the germ of virtue, and prepares fit tools for the designs of ambition.

Free Men

We should resist the temptation to dismiss Jefferson's fears by ascribing them to agrarian mysticism. As Drew McCoy shows in The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian America (1980), Jefferson's apprehensions about the tensions between a booming economy and a sturdy republic were widely shared among America's founders. Even Benjamin Franklin, the prototypical shrewd Yankee go-getter, wrote in 1773, "Farmers who manufacture in their own families what they have occasion for and no more are perhaps the happiest people and the healthiest." Franklin had earlier expressed the belief that "no man who can have a piece of land of his own, sufficient by his labor to subsist his family in plenty, is poor enough to be a manufacturer and work for a master." (The word "manufacturer" in the 18th century could signify anyone who made articles or materials, by hand or by mechanical power, as well as the owner of such shops of factories.)

The husbandman, being in the ultimate commodity business, sells products to customers who neither know nor care about his manners and spirit, which means he has no reason to adjust them to please his buyers. Jefferson thought it impossible for a man to spend his days cringing and flattering in front of a boss's desk or from behind the counter to his customers, and then acquit himself after-hours as a confident, candid citizen who discharges civic duties by clearly assessing the objective public interest, rather than pursuing the private concerns that dominate his working and waking life.

Arthur Miller's epitaph for Willy Loman, his protagonist in Death of a Salesman (1949), describes the vulnerability of those unable to rely on heaven and their own soil and industry for dignity and survival. All such must submit to the life-long grind of winning and keeping the good opinion of the people to whom they sell their products and services. That good opinion often needs to encompass not just the quality and price of the goods or services for sale, but the attractiveness and worth of the people who bring them to the market:

For a salesman, there is no rock bottom to the life. He don't put a bolt to a nut, he don't tell you the law or give you medicine. He's a man way out there in the blue, riding on a smile and a shoeshine. And when they start not smiling back-that's an earthquake.

By 1859 America's economy was more complex and less agrarian than the one Jefferson had known in Virginia. The portion of the labor force engaged in agriculture fell from 74% in the 1800 census to 53% in the 1860s. Nonetheless, Abraham Lincoln contended that every American still had sufficient capacity to avoid dependence and subservience. Speaking that year before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society, Lincoln—a recently defeated senatorial candidate and a prospective presidential one—quickly dispensed with Jeffersonian praise of the husbandman's singular virtues: "My opinion of [farmers] is that, in proportion to numbers, they are neither better nor worse than any other class." Lincoln believed that through their own industry men in all occupations could secure their livelihoods and honor. Looking to heaven and their own soil was one way, but neither the best nor only way: "In these Free States, a large majority are neither hirers or hired. Men, with their families—wives, sons, and daughters—work for themselves, on their farms, in their houses and in their shops, taking the whole product to themselves, and asking no favors of capital on the one hand, nor of hirelings or slaves on the other."

The crucial point for Lincoln was that the only Americans forced to ask for favors were those who would not or could not take advantage of the nation's abundant opportunities:

The prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself; then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him. This, say its advocates, is free labor—the just and generous, and prosperous system, which opens the way for all—gives hope to all, and energy, and progress, and improvement of condition to all. If any continue through life in the condition of the hired laborer, it is not the fault of the system, but because of either a dependent nature which prefers it, or improvidence, folly, or singular misfortune. [Emphasis added.]

Creative Destruction

Lincoln was describing a reality that had existed, but which was giving way to a new and very different one. The census of 1800 did not even have a category for manufacturing workers but by 1860 they accounted for 14% of the labor force, with another 8% in trade. After seven subsequent decades of industrialization, the Depression was not only an economic calamity but marked the final disappearance of the world that Jefferson and Lincoln had known and hoped to perpetuate, one where "the system" condemned no one to "continue through life in the condition of the hired laborer." The percentage of the labor force engaged in agriculture continued to decline, to 22% in 1930 (and less than 2% by 2010), while 37% were in manufacturing or trade. Employment in, and dependence on, large enterprises manufacturing goods or providing services became the rule. The official statistics do not give distinct categories for the self-employed, or the size of enterprises, but a reasonable inference is that fewer and fewer employed Americans worked alongside their employer in small enterprises, while more and more worked with hundreds or thousands of others for a boss that none of them ever met or could realistically hope to emulate. As the late political scientist John Wettergreen put it:

The Great Depression [struck] a fatal blow against the bulwark of Jeffersonian democracy, the middle class—that is, the small-business men and small farmers who had been assumed by politicians of all types to be the backbone of the nation. One should not be complacent about this; the Great Depression, together with World War II, left us what we have been ever since, a nation of wage workers; 95 percent of us are without independent means of subsistence in the Jeffersonian…sense.

One of the New Deal's forgotten battles was to re-secure a defensible space for those who were not wage workers. The Second Bill of Rights included planks that would codify that concern by committing the government to guarantee "The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living," as well as, "The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad."

Even the liberal legal scholar Cass Sunstein, who devoted a book to celebrating the 1944 State of the Union Address as the greatest speech of the 20th century, was dubious about this effort. Rather than guarantee farmers' profits, he would have government acknowledge, "In fact some farmers should go out of business. There is no more reason to guarantee ‘every' farmer a reasonable profit than to make this guarantee for computer companies, airlines, or real estate agents." It follows that some airlines, real estate agents, and other enterprises of all types should also go out of business, and even that some entire industries that once made profits and played a valued role—travel agencies and video rental stores are examples—should disappear.

One of today's most committed champions of the New Deal, then, acknowledges the futility and damage from attempting meteorological interventions meant to abate what economist Joseph Schumpeter called capitalism's "perennial gale of creative destruction." Lest we miss the point, Schumpeter resorted to lectern-thumping repetition in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942): "This process of Creative Destruction," which is "the essential fact about capitalism," is one that "incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one." Marx and Engels had made the same argument a century before in the Communist Manifesto:

Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condition of life and his relations with his kind.

Since the Marxist program for controlling and then expropriating this rollercoaster has failed and been abandoned, we are left to devise the best way to survive and enjoy the ride. The liberal response aims to mitigate creative destruction by regulating the process itself, and by redistributing some of the gains made by those shrewd or lucky enough to participate in rising firms and industries to those obtuse or unfortunate enough to have thrown in their lot with declining ones. The conservative position is that liberalism's interventions do more harm than good, stifling prosperity and jeopardizing liberty: we are better advised to accept creative destruction as a package deal that will ultimately help everyone, even those it harms in the near- and mid-term. As Mitt Romney is shown saying to a group of college students in the Winning Our Future film, "Creative destruction does enhance productivity. For an economy to thrive as ours does, there are a lot of people who will suffer as a result of that."

Take This Job

Neither position deals with our situation adequately. Believing that spontaneous order is a better bet than liberalism's engineered disarray, conservatives contend that the problem with messing around is that it routinely leaves things a mess. Worse still, if politician-manager-intellectual types get carried away with their use of plenary government power to build the society they think we want or should want, they may wind up impoverishing or even imprisoning us.

Having said everything there is to say about the harm government can do to us, conservatives would do well to give equal emphasis to the harm it can do to itself. When government undertakes tasks for which it is ill equipped it squanders the authority necessary for carrying out its core responsibilities. Pervasive rent-seeking, bad for our economy and worse for our republic, should be discouraged instead of rewarded. If government becomes integral to securing every advantage and assuaging every grievance, then governance becomes impossible. We do our republic no favors by promoting the belief that government can and should acquire, as FDR said in 1936, "the vibrant personal character that is the very embodiment of human charity," in order not merely to "share the wealth" but to impart "the true sympathy and wisdom [that] helps men to help themselves."

A republic's government cannot be that sympathetic and wise, and should not be that powerful. Given the extent and limit of the president's important constitutional duties, there's no reason for him to know or care that my boss is a son of a bitch, nor for me as a citizen to care whether he cares. Barbara Walters revealed, idiotically but clarifyingly, the depths to which a regime committed to embodying human charity will descend when she concluded a television interview 35 years ago by imploring president-elect Jimmy Carter, "Be wise with us, Governor. Be good to us."

When an American says, "Don't tread on me," he's supposed to be warning, not pleading. Someone who hates his job should not seek help from the president, the National Labor Relations Board, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, or the California Task Force to Promote Self-Esteem and Personal and Social Responsibility. He shouldn't, in general, beseech some politician-manager-intellectual type to be wise with him and good to him.

No, what an American who is miserable at work, all day and every day, ought to do is walk into his boss's office and tell that son of a bitch to take this job and shove it. The country song by that title, though remembered as an anthem of defiance, was actually a lament for the prohibitive cost of defiance in a nation of hirelings. The song's protagonist makes clear that after working "in this factory for nigh on fifteen years," he knows what he wants to tell his boss before walking out the door. But it is precisely what he hasn't said, and probably never will, because he only wishes he had the "guts" and the "nerve" to quit so boldly. For the handful of listeners unsure why workplace courage was difficult to summon, the singer on the 1977 country hit had fortuitously changed his name in the 1960s from Donald Lytle to Johnny PayCheck.

We should want a society where people lacking a hero's guts and nerve still have ways to find employment they don't detest. The point is not to build an insolent nation but a free one. No longer possessing an immensity of land courting the industry of the husbandman, we must still contend with Jefferson's dilemma: we can't count on people whose adult lives are spent biting their tongues as employees to speak their minds as citizens.

The single most important requirement for minimizing the number of people stuck and stifled in dead-end jobs is a strong economy and a tight labor market. If there are attractive employment opportunities elsewhere, no one will waste nigh on 15 years seething about working for the "dog" or "fool" that David Allen Coe's lyrics described—Jane or Jack Paycheck would have long since moved on to a better gig. And even the fools who run the enterprise the Paychecks quit would eventually realize they'll have to comport themselves so as to attract and retain the workers their business depends on. As Adam Smith explained, it is not from the benevolence of the employer that we expect to be paid competitively and treated respectfully, but from his regard to his own interest.

Who's In Control?

If there were a prosperity button the government could push, the problem of being trapped in, much less desperate to fill, bad jobs would have been solved long ago. There appears to be no recipe that guarantees the strong growth and low unemployment Americans enjoyed in the early 1960s, middle 1980s, or late 1990s. Until that formula is discovered, we must concede that macroeconomic policy proposals do not get us to the heart of the matter. Too many people are dubious about capitalism, despite the awareness that there are no alternatives to it. C.S. Lewis acknowledged that every new cancer diagnosis made it a little harder to believe in God. In the same way, every downsizing or home foreclosure makes it a little more difficult to accept that giant corporations and investment banks are led by an invisible hand to promote society's best interests simply by pursuing their own. Recessions make the destructiveness of capitalism more palpable than its creativity. And if, in a nation of employees, we feel diminished and vulnerable when economic necessity keeps us stuck in a bad job, that fear turns into terror when a firing or plant closure raises the prospect of being homeless, without health insurance, or otherwise consigned to society's shadowy margins.

Conservatives need to address these doubts with a compelling account of democratic capitalism. The liberal understanding of that concept is long-settled. In 1932 Franklin Roosevelt said, "The day of the great promoter or the financial Titan…is over…. The day of enlightened administration has come." Its work will consist of "modifying and controlling our economic units."

The results of that 80-year experiment are in: administration is seldom enlightened enough to carry out the broad mandate FDR gave it, and democracy is less likely to temper than be corrupted by this administration. The "economic units," that is, do not submit meekly to being modified and controlled. Rather, they have every incentive to use every available political means to modify and control the enlightened administrators ostensibly modifying and controlling them. Entrepreneurial energies that would otherwise be devoted to improving goods and services; strengthening relations with investors, suppliers, and customers; and discerning and responding to market signals will, of necessity, be redirected to winning friends and gaining influence among regulators and legislators.

In the competing conservative version, democratic capitalism means that more and more people have a stake in the system, in a way that is neither mediated by government nor limited to being hired laborers dependent on other people's capitalist practices. The woman in Marion, Indiana is correct—as a general partner of Bain Capital, Mitt Romney was a "money man" looking out for the "money people." Specifically, he had raised millions of dollars when Bain Capital was founded, not by persuading individuals and institutions to donate to a charitable organization, but by persuading them that the risk they would lose some or all of their money was outweighed by the prospect they would realize a handsome return on it. Romney would have violated his obligations to those investors by perpetuating an enterprise Bain could not make profitable in order to avoid disrupting the lives of its employees or the equanimity of the city where it was located.

The woman's complaint that Romney had the capability yet failed in his duty to care for AmPad and Marion's "little peons" does not hold up under scrutiny. The fact she feels that American economic life has reduced her and her friends to peonage, however, is a sentiment no one who cares about capitalism's political prospects, or America's republican future, can disregard. A nation of employees becomes an electorate that listens—bemused, skeptical, or infuriated—as competing elites argue about whether the partisans of enlightened administration or the partisans of spontaneous order will do more to augment the quantity and quality of the nation's jobs.

What's missing from both appeals is a democracy of agency. One small group of Americans, with degrees from famous colleges and boundless confidence in their own intelligence and motives, proposes to regulate capitalism; and another small group, equally credentialed and self-satisfied, proposes to practice it. The rest of us are left to make an Election Day choice on the basis of incomprehensible arguments we can't evaluate, and spend all the other days of the election cycle hoping that the group that won meant what it said, knows what it's talking about…and has more good luck than bad.

Capitalism will receive and deserve greater political support by steadily becoming something more people do and fewer people have done to or for them. The necessary changes will have more to do with the conduct and even the sociology of capitalism than with public policies. The most fundamental change would be for Americans to become a nation of savers. Household savings rates in the U.S. have been below 5% for most of the past two decades, among the lowest rates in the developed world. The best safety net is the one families build and own, giving them the wherewithal to get through tough economic times and take the risks of seizing more promising employment and business opportunities.

A Nation of Investors

Economist Martin Weitzman advocated another idea to moderate the business cycle from within. In The Share Economy(1984), he proposed a system where employees' compensation would be based, in large part if not entirely, on receiving an agreed-upon percentage of the employer's revenue stream. During good times paychecks would automatically increase, while the automatic reductions during downturns would curtail the need for layoffs. Weitzman's principal concern was to provide a stabilizing macroeconomic alternative that would see the business cycle move gently rather than violently between inflationary booms and recessions.

But the share economy also strengthens capitalism at the microeconomic and even moral level. In the "wage system" Weitzman wants to replace, employees receive a stipulated amount of dollars, which employers generally try to continue for as long as business conditions permit…and then reduce to zero when that compensation level becomes unsustainable. The share system, by contrast, would banish "the illusion that the welfare of a firm's employees is independent of the economic condition of the employer." In an economy where employees prosper when their firms prosper and suffer when their firms suffer, all become, in effect, capitalists. It is not from the employer or employee's benevolence but from their mutual self-interest that we expect them to work together to expand the pie they've agreed to divide.

The greatest monument to the illusion that employees can and should prosper regardless of the economic condition of their employer is the rusting ruin that's the American labor movement. In Which Side Are You On? (1991), labor attorney Thomas Geoghegan lamented that the failure to take the biggest equity position it could in the industries where it represented workers "was the longest-running mistake in the history of labor, the unwitting, almost Gandhi-like renunciation of power." Geoghegan's explanation is that unionists were so strongly committed to the idea that workers and employers' relationship had to be adversarial that they never accepted the possibility of it being collaborative. "The attitude in labor was: collective bargaining is for adults, stockholder meetings are for kids."

And despite all the rhetoric about "solidarity," labor's acquiescence in the layoffs that Weitzman's share economy would obviate reflects an "I've-got-mine" outlook, red in tooth and claw. As Geoghegan wrote, "Once people become unemployed, even if they were always good union members, they are out of the labor movement. They become lepers, or untouchables: they become, at least potentially, scabs."

Non-spurious solidarity was economically important when America was a nation of joiners. From Mutual Aid to the Welfare State (2000), by historian David Beito, shows how social capital and economic capital can reinvigorate one another. He describes how fraternal societies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, emphasizing "mutual aid and reciprocity," pooled members' resources to provide life and health insurance, and to establish clinics, hospitals, orphanages, and homes for the elderly. As Beito chronicles, once the New Deal asserted that the government, not voluntary private organizations, was the proper source of this kind of assistance, fraternal organizations, their endeavors made redundant, went into a steep decline.

Conservatives should promote the revival of that approach, and foster others, to make Americans true stakeholders in our private enterprise system. To paraphrase John Dewey, the cure for the ailments of capitalism is more capitalism. "More capitalism" means steadily increasing the number of Americans with a piece of the action, while decreasing the number whose only connection to free enterprise is filling the jobs that successful ventures create and being laid off from ones that faltering enterprises destroy.

The word "invest" originally meant to endow with authority, as when donning garments that showed military or clerical rank. Conservatives want more Americans, and ultimately all Americans, to be investors, endowed with authority over their families' destinies and the economic life of the nation. Advances toward that result mean advances toward the goal Lincoln described 153 years ago, when many Americans could aspire to be self-employed. Today, most of us spend most of our lives as hired laborers. That fact makes it all the more important to constantly extend and deepen confidence in our economy as a just, generous, and prosperous system, one which opens the way and improves conditions for all, giving energy, progress, and hope to all.

* * *

For Correspondence on this essay, click here.