Books Reviewed

In 1993 the president of the American Society for International Law called for a “campaign to extirpate the term [‘sovereignty’] and forbid its use in polite political and intellectual company.” Such a proscription would have been in keeping with the bien-pensant consensus at the end of the past century and beginning of the present one: sovereignty is becoming obsolete and needs to be diluted or shared as mankind progresses toward global governance.

Nonetheless, Donald Trump, Brexit, and the growing resistance to increased centralization by the European Union from its member nations show that sovereignty has returned with a vengeance. This interruption of the inevitable march to globalism creates a problem for the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), central command for “liberal internationalism,” more accurately described as “transnational progressivism.” From the CFR perspective, the issue is how to defeat the American sovereigntists and their case for democratic self-government. This task is taken up in The Sovereignty Wars: Reconciling America with the World, by Stewart Patrick, director of CFR’s International Institutions and Global Governance program.

* * *

Patrick writes well, is knowledgeable, informative, a pleasant fellow, but he is wrong on the most important issues concerning democratic sovereignty and the right of a free people to rule themselves. His first priority, in effect, is to deconstruct the concept of sovereignty into its constituent but discordant elements, which he sees as threefold. At the top of his framework, “the Sovereignty Triangle,” is authority, which, with respect to America, “implies that the Constitution is the supreme law of the land and no external constraints should limit Americans’ right to govern themselves.” The triangle’s second vertex is autonomy, which “implies that the U.S. government, acting on behalf of the people, should have the freedom of action to formulate and pursue its foreign and domestic policies independently.” The final corner is influence, “the state’s effective capacity to advance its interests,” hence, America’s ability to influence others.

Though these three aspects of sovereignty are “often in tension,” sovereignty itself can be “disaggregated” when we “voluntarily trade off one aspect of sovereignty for another.” These “sovereignty bargains” will be “required” if the United States is to exert influence and shape the future of globalization. Indeed, it is “counterproductive” for sovereigntists to worry too much about autonomy or even authority—the supremacy of the Constitution—because influence is what America most needs “to shape its destiny in a global era.” Patrick concedes that a “liberal internationalist” would prioritize “solving a global problem” through multilateral action “even if that implied a loss of autonomy or, conceivably, even authority.”

Sovereignty Wars, and transnational progressivism generally, argue that in an interdependent age American interests and values are best advanced in a global order wherein all nations, including the United States, are constrained by global rules. Patrick and his allies decry what they call “American exemptionalism,” the attempt by sovereigntists to exempt Americans from global rules that others allegedly adhere to. American “leadership” is to be judged by how well our nation “leads” in the creation and formulation of these transnational and sometimes supranational “rules” to which all states are supposedly bound.

To be sure, Patrick tells us that “a global state is a terrible idea,” neither achievable nor, given the enormous practical barriers to creating a single world democracy, desirable. The attainable solution is global governance under a rules-based order. He notes that “even Immanuel Kant based his vision of perpetual peace not on a single world state but on a confederation of independent liberal republics.”

* * *

Despite sounding reasonable enough, the reconciliation with the world Patrick proposes is determinist, partisan, and, most importantly, challenges America’s constitutional self-government. Because of his determinism, the author’s favorite word appears to be “require.” Thus, increasing interdependence and global integration “will require more extensive multilateral collaboration in negotiating new legal obligations.” The future will “require sovereignty bargains whereby the United States…trades off…autonomy for the promise of effective multilateral action.” Even American immigration policy “may require some psychological adjustments on the part of Americans” because controlling our border, according to Patrick, is not something that nation-states like the U.S. can do unilaterally but “is likely to require bilateral and multilateral cooperation.” He is apparently unfamiliar with Israel’s successful unilateral border enforcement.

This framework is a direct challenge to a core premise of the American experiment in self-government. In the very first paragraph of The Federalist, Publius repudiated determinism, suggesting that Americans would decide the important question whether “societies of men” are capable of “establishing good government from reflection and choice,” rather than having these questions forever determined for them by “accident and force.”

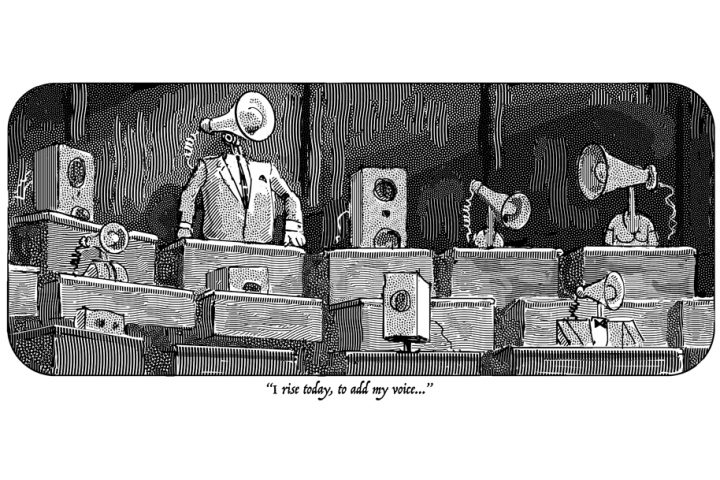

Behind Patrick’s determinism is transnational progressivism, which holds that national sovereignty (including democratic sovereignty) must be attenuated because “global problems require global solutions.” Hence, global or supranational institutions and a binding “global rule of law,” are necessary in the coming interdependent world to achieve “global governance.” This globalist order is different from an internationalist framework built on relations between sovereign nation states: in the former, nations cede crucial elements of sovereignty to transnational and supranational institutions. In the words of American John Ruggie, the United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Business and Human Rights, “We have entered a global world” as opposed to simply an inter-national world. Thus, it is necessary “to devise more inclusive forms of global governance.”

Transnational progressivism is connected to influential institutions and organizations like the U.N., E.U., World Trade Organization, International Criminal Court, World Council of Churches, and powerful corporations and NGOs (non-governmental organizations). Patrick makes no reference to globalist ideology, its material interests, or to the transnational superstructure that forms its support network. Instead, he stacks the deck by framing a debate between “suspicious,” “inward-looking” sovereigntists and “optimistic,” “outward-looking” globalists. He mischaracterizes the sovereigntist support for constitutional supremacy and democratic self-government as “alarmist,” “hyperventilating,” “overblown,” “imaginary,” “exaggerated,” and “overwrought.”

* * *

The book’s main substantive argument is that delegating aspects of our democratic sovereignty to multilateral institutions serves American interests and values by gaining the good will of others. Since the United States is declining in power, relative to other nations, it is best to get on with these multilateral agreements. The realities of multilateral rules and their implementation are, however, far less reassuring than Patrick’s theory.

Consider some treaties that the U.S. has refused to join, but that Patrick insists would promote “our interests” and “our values.” The U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child declares that a child has the right “to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds…through any other media of the child’s choice” including correspondence with anyone in the world without interference from the child’s parents.

The U.N. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities does not define “disabilities” but simply calls it an “evolving” concept. The treaty requires the enforcement of positive rights (rights promoted by governments) including “political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other” rights. American homeschooling groups, cognizant of how U.N. mandates are enforced, believe that the treaty would threaten parental rights and existing state laws on homeschooling. They point out that the U.S. already has the strongest laws against discrimination for the truly disabled, notably the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The U.N. convention on the Law of the Sea stipulates that maritime disputes between the U.S. and other nations will be settled by “mandatory” arbitration, with final decisions made by a 21-member international tribunal. Currently, that tribunal is packed with progressive-left judges from around the world, including some from unfriendly states.

The U.N. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) explicitly rejects legal equality and equality of opportunity for women in favor of “substantive equality” or “de facto equality,” i.e., equality of result based on proportional representation in the population. CEDAW calls for gender quotas in public and private institutions, including in elected legislatures where women receive fewer than 50% of the seats.

The U.N. Arms Trade Treaty requires nations to “establish and maintain a national control system” including a “national control list” for small arms. Several years ago, John Bolton and John Yoo argued that if the U.S. joined the treaty, gun control advocates could use its provisions to restrict Second Amendment rights.

In short, these treaties serve the interests and values of the global progressive elite who promote, implement, interpret, and enforce the treaties, rather than of the American public. For good measure, Patrick also believes that the U.S. should adhere to several dubious multilateral agreements and retain memberships in several flawed U.N. institutions, including the Paris climate accord; President Obama’s agreement with Iran on nuclear weapons; the U.N.’s New York declaration for refugees and migrants, which endorses mass Third World immigration to the West; the U.N. refugee program, which discriminates against Middle Eastern Christians; and the U.N. Human Rights Council, dominated by dictatorships.

* * *

A revealing section of Sovereignty Wars notes that the United States, more than other nations, attaches “Reservations, Understandings, and Declarations” to many treaties, which limit our nation’s obligations under those treaties. Patrick frets, for example, that in signing the U.N. Convention Against Torture, “the United States insisted that it would interpret the convention’s prohibition on ‘cruel and degrading treatment’ according to the Fifth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution.” In other words, Americans insist on interpreting our treaty obligations within the framework of the Constitution—as opposed to the preferred global progressive method of formulating an “evolving” principle of international law as interpreted by a European or American academic now serving on, say, the staff of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights.

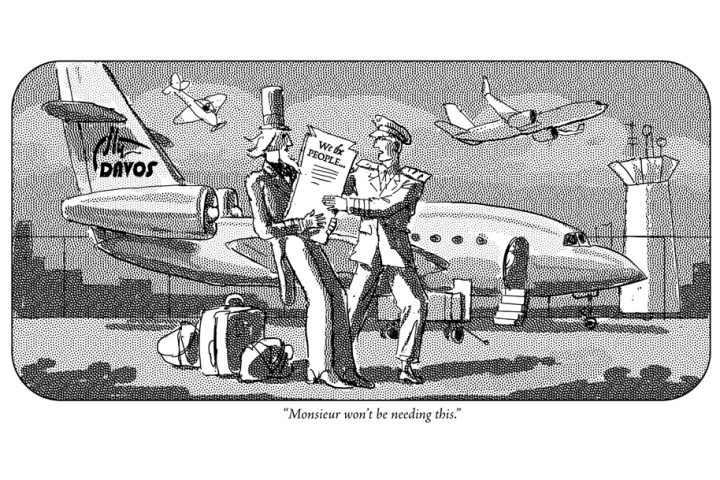

The transnationalists’ arguments that global governance is really about American interests and values, and is therefore required by American “leadership,” has been with us for decades. Just before the 1992 election, Strobe Talbott (later the president's deputy secretary of state and currently a Brookings Institution scholar after serving for many years as its president) told his old Oxford roommate Bill Clinton that Americans “are mighty chary about any arrangement that smacks of pooled national sovereignty,” but that the “way to counter this resistance” is to “sell multilateralism” as a means of “preserving and enhancing American political leadership in the world.” In other words, America will “lead” by following transnational progressivism as promulgated by the “High Minded,” in John Bolton’s term, at places like the U.N., E.U., The Hague, and Davos. This sounds like the worst kind of leading from behind.