Books Reviewed

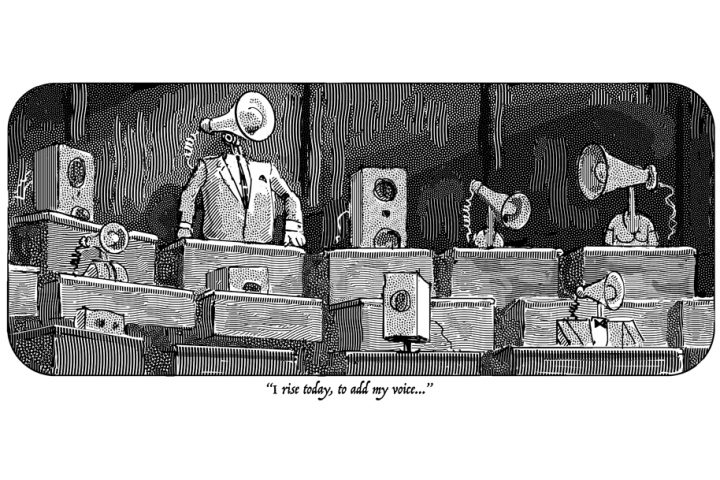

Americans, it seems, can never get enough race talk. We speak of race incessantly, yet continue to call for more, in the persisting hope that more talk will yield better talk. What we want—or so we say—is an honest conversation about race.

That we call almost metronomically for a conversation we do not expect to have attests both the importance and the sensitivity of the subject. An honest conversation about race is important as a means for healing and unity, even more so as an imperative of national honor; America cannot be America, in the full and proper sense, until our race problem is resolved. Given, however, the unique sensitivity of the subject, we expect our race talk to be clouded by evasion or dishonesty; for in the matter of race, everyone has something to hide.

Historian Gene Dattel agrees that “[w]e need a frank and honest discussion about race,” but advances the conversation in ways that defy expectations. A former managing director at Salomon Brothers and Morgan Stanley turned scholar, Dattel is free from the academy’s pressures and pieties. His powerful new book, Reckoning with Race: America’s Failure, aims to replace our ritualized race talk with a true national self-examination. There is something in his survey of black-white relations from the founding to the present to discomfort nearly everyone. His proposed remedy is at once edifying and challenging.

Dattel’s story unfolds chronologically but may be summarized in three general claims:

America’s race relations failure is above all a failure to commit the nation to full integration or assimilation (Dattel insists on using the latter, lately more incendiary term).

The failure to make this commitment is America’s failure, belonging to the country as a whole—not to any particular region, class, party, or generation.

The crucial condition for assimilation is a concerted effort in self-help or cultural renewal by black Americans.

Dattel is particularly concerned to dispel the myth of Southern exceptionalism—the supposition, widely held outside the South, that “the South [is] the exclusive and durable” cause of “America’s racial ordeal.” Though he objects to viewing the South as an exclusive scapegoat, he is no apologist for the Confederate cause. He means only to apportion blame fairly by pointing out that 19th-century Northern whites were never so much anti-slavery as anti-black, and that for most of the 20th century opposition to racial equality and integration was hardly less powerful outside the old South than in it.

* * *

Dattel substantiates these claims in abundant detail. “Blacks constituted a mere 2 percent of the North’s antebellum population,” he notes, “and 94 percent of them were not allowed to vote.” From the founding onward, Northern whites from the Great Lakes region to New England objected to the presence of even small numbers of blacks in their communities. They imposed legal disabilities on those already present and labored to prevent further migration. When Stephen Douglas tarred Abraham Lincoln and Lincoln’s party with the name “black Republicans,” he accurately saw the political advantage in it. Dattel quotes Republican Senator John Sherman affirming, on the floor of the Senate in 1862, that blacks were “spurned and hated all over the country North and South.”

Such sentiments did not materially change in the post-Civil War years—indeed, they remained powerful a full century later. The prewar policy of containing slavery, as Dattel observes about the Wilmot Proviso, was for most of its supporters a policy for containing America’s black population in the South. That policy persisted well beyond the Reconstruction years. Though the Great Migration ended regional containment in the early 20th century, the states into which blacks migrated in large numbers soon contrived a substitute—residential segregation—and thus originated the urban ghettos in which many blacks languish to this day.

Life in the North had its own demoralizing and radicalizing effects, beyond the residuals of Southern conditions. Dattel recounts the emergence of Northern ghettos via brief but revealing case studies of Chicago, Detroit, and New York. Residential segregation also meant school segregation, which obstructed the only viable path for black advancement. “[W]hite flight,” writes Dattel, signified a Northern “form of massive resistance to racially mixed schools.” More generally, he observes that in Chicago as elsewhere, “blacks met with discrimination and ostracism” in “every aspect” of life. “Vice and crime proliferated,” and “racial friction escalated.” Race riots broke out in Chicago in 1919, in Harlem in 1935, and in Detroit, Los Angeles, and Harlem again all in 1943, precursors to those that erupted in hundreds of American cities in the mid-1960s.

* * *

The villains in Dattel’s story are the separatists, whether white or black. In its strict, nationalist form separatism has never been a majority position among black Americans, but it has long had prominent advocates, including 19th- and early 20th-century emigrationists such as Martin Delany and Marcus Garvey, and, in the Civil Rights era, black nationalists such as Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael. Recently, attenuated or disguised variants have gained mainstream legitimacy through the insinuation of diversity and multiculturalism into the integrationist cause.

Racial separatism, Dattel argues, is a chronic danger to our unity and stability, and gravely endangers the cause of black elevation. He observes among blacks in the Civil Rights era and beyond an increasing tendency “to view matters exclusively through a racial lens,” accompanied by a deep sense of alienation and a spreading hostility to assimilation. Among the urban poor, this alienation appears in young males’ disengagement from school and work, and most glaringly in the incidence of violent crime. Among elites, it appears in the reverence accorded socialists and illiberal black nationalists such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Malcolm X, and, recently, in the generally uncritical approval of the Black Lives Matter movement. On campus, it appears in a rising incidence of self-segregation (both residential and curricular), and, at the K-12 level, in rejections of common academic and disciplinary standards as racially or culturally biased.

Racial separatism is doomed to fail, Dattel argues, even when accompanied by a spirit of industry and economic self-reliance, as in the laudable efforts of Booker T. Washington and the Montgomery family (the late 19th-century founders of Mound Bayou, a briefly prosperous all-black community in the Mississippi Delta). It is particularly self-destructive in post-Civil Rights era America, in which opportunity is widespread and “values count more than race” as determinants of success and failure.

* * *

Reckoning with Race is well researched and loaded with illuminating details. Better still, Dattel writes to revitalize a venerable tradition of wisdom on race, guided by two lodestars: full integration across color lines—equal rights under law as well as cultural assimilation—is a moral imperative; and integration requires a struggle on “two fronts,” as Martin Luther King, Jr., put it, both for liberty and for the virtue required for liberty’s fruitful exercise. Recent failures stem from a refusal to accept victory on the first front and a demoralized retreat from the second.

The great question, then, concerns how we might redirect opinions and energies to repair mores and reconstruct civil society. This question points to my one significant reservation about this excellent book.

In his concluding remarks Dattel sensibly observes that the lately prevalent “reinterpretation of American history as one extended nightmare of grievances is psychologically retarding”—fostering debilitating sentiments of futility and alienation. In his telling, however, the story of America’s failure on race is one of unbroken resistance to full integration across color lines, and most of that history—recounting the rejection of integration by ruling majorities of racist whites—closely resembles the “extended nightmare of grievances” whose demoralizing effects rightly concern him.

The difficulty, in short, is that the history Dattel presents stands in tension with the remedy he prescribes. The story of America’s chronic resistance to full integration may highlight the need for it, but it may also bolster the racial pessimists who see in that story the futility of hoping for a post-racial America.

Such pessimism is not exclusive to the likes of Derrick Bell and Ta-Nehisi Coates. When Thomas Jefferson explained in his Notes on the State of Virginia why he believed the incorporation of blacks into American society was impossible, the first two and the strongest of the causes he noted were “deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites” and “ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained.” Those two factors would operate in symbiotic relation: prejudices would persist, injustices would accumulate, and the “ten thousand recollections” of injury would generate among blacks a simmering stew of humiliation, indignation, and anger.

* * *

Long after subjection to actual injustice has been overcome, its memory endures. Here is the destructive operation of what Shelby Steele has called the “enemy-memory,” also recognizable as an updated expression of the psychological dividedness that Du Bois both decried and propagated—the sense that to be “a Negro” and to be “an American” signify “two warring ideals.” For many blacks in what should be a golden age of integration, the release of long-harbored, long-suppressed resentments produces a profound psychological conflict between pride and interest, with the latter dictating assimilation into the American mainstream and the former fueling resistance to it. The proposition that blacks should adopt the values, even the virtuous and beneficial ones, of those who had tyrannized them stirs a powerful sentiment of revulsion.

To note the demoralizing effects of those “ten thousand recollections” is not to recommend any whitewashing of the nation’s history as a remedy. It is instead to suggest that although much of our history may aggravate the malady Dattel diagnoses, other portions can help ameliorate it. His history might be usefully leavened by more of the spirit of hopefulness that animated the black leaders he most admires, Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass—a spirit that surely holds a more solid historical grounding now than it did during their lives.

America’s founders temporized and equivocated on race, and later generations of reformers, including abolitionists, Reconstruction-era Republicans, and Civil Rights-era leaders, were in their own ways imperfect as apostles of justice for all. Even so, the founders dedicated the nascent republic to principles that, as Douglass observed, “would release every slave in the world.” Their successors drew vital inspiration from those principles as they collaborated, over time, in the accomplishment of momentous and by all appearances irreversible reforms. In the wake of those reforms, black Americans have achieved unprecedented success in unprecedented numbers. Writing in the late 1990s, the sociologist Orlando Patterson extolled the brighter side of the country’s history on race: “The achievements of the American people”—black and white—“over the past half century in reducing racial prejudice and discrimination and in improving the socioeconomic and political condition of Afro-Americans are nothing short of astonishing.”

Race, as Gene Dattel argues, is America’s failure—to which one must add, it is also among America’s great successes. That success has been achieved fitfully and incompletely, with advances and reversals and no small incidence of violence. It supplies no cause for complacency. Yet the nation’s success in this monumental task must not be downplayed or obscured, for its recognition is an indispensable stimulus for further efforts.