Books Reviewed

President James Buchanan is credited with being the first to call the U.S. Senate “the world’s greatest deliberative body.” This designation has been repeated frequently in the years since, almost always by senators themselves. These days the epithet rings hollow, and the senators know it.

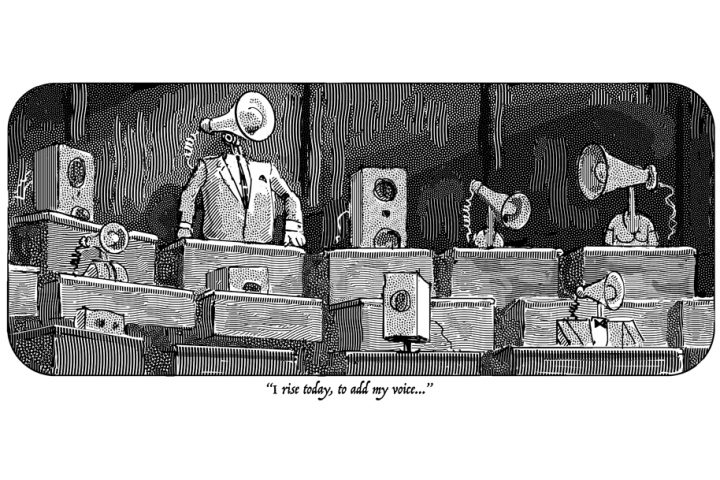

Speeches in the Senate are typically given to a room of two or three senators, and no one is listening. When Senator Jeff Flake (R-AZ) condemned President Trump’s criticism of the press in a dramatic speech on the Senate floor in January, only a few senators bothered to show up. He was, in essence, speaking to the media and not to his colleagues. The Senate’s presiding officers spend more time on their phones than paying attention to the debates, because debate is mostly nonexistent.

Nowadays when senators invoke the ideal of the “world’s greatest deliberative body” they talk about restoring deliberation rather than preserving it. Senators Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and John McCain (R-AZ) have in recent years delivered floor speeches (again, unattended by other senators) on restoring Senate deliberation. Members’ contempt for their own institution is bipartisan. When Democratic Party leaders pleaded with Joe Manchin (D-WV) to run for reelection, he told them simply, “This place sucks.” (He’s running anyway.)

It’s not going any better on the other side of Capitol Hill in the House of Representatives. We are all aware of the periodic “showdowns” over government “shutdowns” over the debt limit or whatever—which have become a common rather than an extraordinary feature of congressional life. The floundering was on full display in Republicans’ attempts last year to reform health care. The legislative process was so secretive in that instance that ordinary citizens could not be expected to understand how the bill to “repeal and replace” Obamacare was amended or debated. Even many House members seemed to be in the dark about what they were actually voting on.

Things became so unpleasant for John Boehner by 2015 that he resigned from the Speakership and from Congress, leaving Paul Ryan, who now himself has one foot out the door, to deal with the messy business of presiding over the House. Ryan had to be cajoled by members of his own party to take the job, which nobody seemed to want. Aside from repealing 15 major Obama regulations, last December’s tax reform remains the sole significant legislative reform since Republicans took control of the House, Senate, and presidency in the 2016 election. More members are declining to run for reelection with each election cycle.

Americans continue to have a low opinion of Congress’s performance. At the start of 2018, Congress’s average approval rating from RealClearPolitics was 15%, with 75% disapproval. Nor is this a recent trend: Congress’s approval rating has barely left the teens since Barack Obama’s first term in office. Philip Wallach of the R Street Institute opened a recent article on Congress with this simple statement: “Congress is a mess.” He later acknowledged that there is disagreement among scholars regarding why Congress is mess. Those who analyze Congress are like doctors who can agree that a patient is sick, but can’t explain what caused the sickness or prescribe a treatment. But if we cannot answer these questions, we will be ill-equipped to respond to the growing chorus calling for reform of our most republican institution.

Deliberation in Decline

Congress is complex, so it is much harder than it is with the presidency or the courts to pinpoint the source of its failings. The Constitution sets out few guidelines for the legislative process. History and custom play a significant role in how Congress works (or fails to work) today, and institutional rules channel behavior in a more fundamental way.

Constitutional theory, however, is the necessary starting point for understanding our dysfunctional legislature. The Constitution shapes legislators’ behavior in ways we don’t often perceive. It creates a Congress at odds with itself, seeking representation that is both diverse and deliberative. On the one hand, members should represent different interests, and must bargain and compromise to get things done. On the other hand, the founders also clearly intended to create a Congress that could come to a consensus by carefully considering which policy decisions would best serve the public good. The wide variety of interests reflected in the legislature should promote not just bargaining but “deliberation and circumspection,” as The Federalist put it.

As the late Emory political scientist Randall Strahan explained in Leading Representatives (2007),

while the Founders attempted to design legislative institutions that would foster deliberation, they were well aware that these [quoting The Federalist] “various and interfering interests” would not always be reconciled through disinterested reason or deliberation about the public good…. Negotiation and bargaining would also be involved in assembling House majorities among legislators whose motivations would often be narrower than considerations of the public good.

But what does it mean to deliberate? For Joseph Bessette, a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College and the author of The Mild Voice of Reason (1994), deliberation is “reasoning on the merits of public policy.” This reasoning requires members to be “open to the facts, arguments, and proposals that come to their attention” and willing “to learn from their colleagues and others.” It would seem that deliberation threatens the mere bargaining or “logrolling” approach to representation. After all, if John C. Calhoun was truly open to Daniel Webster’s anti-slavery arguments during the sectional crisis of the mid-19th century, could he adequately advance the interests of South Carolina?

But Bessette argues that this is, to some extent, a false choice. It is true that members of Congress can pursue reelection effectively by shunning deliberation and merely reflecting the views of their constituents. But they can also gain reelection and advance in Congress by engaging in deliberation. A member who represents wheat farmers may become a better advocate for his constituents by educating himself on the issue, and by defending his constituents’ position before other members. “If these arguments are taken seriously by others, then the congressman has contributed to a broader deliberation on the issue at hand.” In this way, “the reelection incentive itself may promote genuine deliberation.”

Like Bessette, James Wallner, a senior fellow of the R Street Institute, observes in The Death of Deliberation (2013) that, through most of the 20th century, this is precisely what happened. In the House, membership on policy committees remained relatively static over several congresses, meaning that the members of those committees were able to specialize in, and engage in effective oversight of, the programs under their committee’s jurisdiction. Measures emerging from committees used to receive deference from members when they reached the floor. The chairs of committees were selected by seniority and became “barons” controlling their specific areas of policy, governed only loosely by a “feudal” Speaker who did not infringe their autonomy. These committees were the locus of deliberation until relatively recently. In the Senate, as in the House, committee chairs dominated the agenda until the 1960s. Norms of collegiality and deference, rather than strict rules, prevented senators from stepping on their colleagues’ toes.

The Congress that Wasn’t

This model of congressional action, in which deliberation occurs at the committee level and different lawmakers specialize in various policy areas, is often referred to as the “textbook” Congress. Given how poorly Congress functions today, scholars are increasingly viewing the textbook Congress nostalgically. We should not romanticize it. In theory, committee government allows Congress to become an expert body equipped with all of the relevant information necessary to make policies that promote the good of the whole nation. In practice, as political scientists admit when they describe the “distributive” model of committees, representatives seek membership on the committees that help them distribute benefits to their constituents. If committees are given deference by outside members, and they are composed of members with concentrated interests, they can delegate power to bureaucracies and then use their oversight powers to ensure that the agencies make policy in their constituents’ favor, rather than promote the common good.

The most famous scholarship on Congress prior to 1990 described, essentially, this kind of Congress. David Mayhew’s seminal work, Congress: The Electoral Connection, published in 1974, flatly stated that “no theoretical treatment of the United States Congress that posits parties as analytic units will go very far.” Members operated in a decentralized environment in which they promoted the narrow interests of their constituents without being subject to party discipline. Richard Fenno, the other great scholar of Congress in this period, wrote Congressmen in Committees the year before, describing how the committee system in Congress enabled members to pursue their electoral interests.

This cynical description of the textbook Congress was perhaps best captured by Morris Fiorina’s justly famous Congress: Keystone of the Washington Establishment, first published in 1977. The decentralization of power to autonomous committees, Fiorina showed, enabled members to gain reelection by avoiding lawmaking and relying instead on bureaucratic oversight. These were the scholars who introduced the phrase “iron triangle” into the American political lexicon to describe the policymaking relationship among representatives, interest groups, and bureaucrats. The textbook Congress, it turns out, wasn’t much of a Congress at all, but a bunch of autonomous oversight bodies. National party leaders were minimal players in this structure, and they acknowledged it. Speaker John McCormack (D-MA) advised freshmen members of the House during the 1960s, “Whenever you pass a committee chairman in the House, you bow from the waist. I do.”

That’s not to say that the textbook Congress was weak. As Fiorina’s title indicated, Congress had become the centerpiece of the modern state. Many scholars affiliated with the Claremont Institute also argued this in their 1989 volume, The Imperial Congress, edited by Gordon Jones and John Marini. But Congress played this role behind the scenes in order to avoid the responsibility that should accompany power in a republic.

Leaders without Followers

As the last several years have shown, this textbook Congress no longer exists. So what replaced it, and why does it matter? The standard argument is that in the “post-reform” Congress party leaders drive the agenda and rank-and-file members sit around helplessly, waiting to be led. After announcing his retirement in 2016 from the House of Representatives, Reid Ribble (R-WI) blasted the concentration of power in party leaders’ hands: “The leadership has 100% say on everything and they drive and direct every decision.”

Many political scientists agree with Ribble’s assessment. Among others, Randall Strahan and the University of Minnesota’s Kathryn Pearson, in her book Party Discipline in the U.S. House of Representatives (2015), have described this shift back to party leadership in the House. Reforms first pressed by Democratic members in the 1970s gave party leaders—and therefore the party caucus as a whole—more authority over committee chairs. These reforms accelerated under Newt Gingrich in the 1990s, whose brief tenure as Speaker dramatically altered the structure of power in the House. Gingrich took greater control of committee assignments, rather than allowing committee chairs to remain autonomous due to the seniority principle. And when he didn’t alter the committees, he simply bypassed them with ad hoc “task forces” charged with writing legislation on important matters like Medicare reform. The “Contract with America” also produced six-year term limits on committee chairs, further reducing the committees’ independence from party leaders.

As a result of all of these reforms, Pearson argues, committees have steadily declined in importance, and “party leaders in the contemporary House of Representatives have accrued considerable power.” Strahan concurs, writing that “Gingrich engineered rules changes that helped establish a new form of party government in the House in which standing committees were more subservient to the majority party and its leadership at any point since the era of powerful speakers during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”

James Wallner describes similar trends in the post-reform Senate. Although some leaders (especially Lyndon Johnson) played a stronger role in directing the Senate prior to the 1980s, the majority leader did not emerge as a strong leader until the ’80s and ’90s. Between the textbook Senate and the emergence of party leadership, the Senate operated under a “collegial” model, according to Wallner, in which all members were free to offer amendments to legislation and debate on the floor. The passage of the Clean Air Act amendments in 1990 by a wide bipartisan majority, after both parties offered dozens of amendments to the bill, reflected this collegial environment.

As Wallner sees it, over time growing polarization forced the Senate to move to a “majoritarian” environment in which the majority leader blocked senators from offering amendments and moved to end debate quickly—methods utilized extensively by Harry Reid (D-NV) when he served as the majority leader from 2007 to 2015. This is the Senate we are accustomed to seeing: an increasingly-majoritarian institution where filibusters are common and the majority party tries to govern without letting the minority party play much of a role.

Wallner argues, however, that the Senate operates under a different model: that of “structured consent” rather than straightforward majoritarianism. In order to accomplish anything in this environment, the majority and minority leaders confer, negotiate, and broker a deal before debate or deliberation even occurs. Decisions are made behind the scenes and rank-and-file members are increasingly shut out of the process, but it does allow the Senate to remain productive in a difficult political environment without resorting to the so-called “nuclear option” to end debate. Wallner argues that this is a dangerous tradeoff: “the contemporary Senate may be viewed as broken. While it continues to produce significant legislation at relatively consistent rates…it has done so largely at the expense of the institution’s deliberative function.” Deliberation in the Senate is replaced by party leaders brokering compromises. According to this account, not merely the Senate but also the House is governed today by centralized party leadership rather than committees or rank-and-file members.

There seems to be some validity to the thesis that in today’s Congress members are led by party leaders. But we must pause to ask: are Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell really running the show? A little over a century ago, House Speakers were called “czars.” Using the same term to refer to Paul Ryan fails to pass the laugh test.

Irresponsible Party Government

Even those who believe that parties and their leaders are dominant in today’s Congress admit the limits of this hypothesis. In Is Congress Broken? (2017), an excellent collection of essays edited by William Connelly, John Pitney, and Gary Schmitt, University of Richmond political scientist Daniel Palazzolo writes that “institutional reforms have strengthened party leaders and weakened committee chairs,” suggesting that this is an important cause of Congress’s inability to deliberate effectively, although he quickly qualifies this claim.

Pearson, too, emphasizes the tools party leaders have in the post-reform Congress. Leaders can punish or reward members “in the allocation of limited committee positions, legislative opportunities, and financial resources.” But although “party leaders have a growing arsenal of carrots at their disposal with which to reward members,” she insists that “their sticks are more limited,” a point which Gingrich himself acknowledged: “I’m not big on punishments, I’m very big on rewards.” Moreover, her central thesis is that party leaders must balance the need to prioritize policy control with the need to maintain majority control. Leaders need to retain their majority, both in the chamber as a whole and within the party, in order to retain their power. This places considerable constraints on their discretion, even forcing them sometimes to use their carrots to strengthen vulnerable members who don’t vote with the party consistently.

Wallner acknowledges similar constraints on party leaders’ power in the Senate. The structured-consent model he describes, in which the majority and minority leader work things out behind the scenes, “is dependent on relatively cohesive parties, as well as majority and minority leaders that are capable of mollifying the demands of their most ideological members without upsetting their [own] negotiations.” But McConnell seems increasingly incapable of holding his own ranks together, and the structured-consent model seems unsustainable as a result of the forces that incentivize members to go their own way.

In the end, although party leaders have regained some authority to control the proceedings of the House and the Senate, both the external environment and Congress’s internal environment limit their control significantly. Externally, members are simply more accountable to their constituents than to their party’s leadership—as the founders intended. Internally, party leaders are chosen by the members, and are their agents. Randall Strahan’s Leading Representatives sought to take on the notion that party leaders are simply agents of the parties they represent. Yet he admitted that party leadership was always conditional. The institutions may provide an opening for leaders to exert their own influence. Leaders like Gingrich found that opening (for a short time), but Boehner and Ryan appear to have had no such luck. In the end, Strahan concluded, “Leaders who neglect representation and deliberation to orchestrate legislative action they favor may be consequential…in the short term, but the structure of the institution and its place in the American constitutional system make it unlikely they will remain leaders in the long term.”

Over the past 20 or 30 years, in other words, party leaders in Congress may have become stronger, but they still remain relatively weak because parties in America are weak. As John Boehner explained to Jay Leno on The Tonight Show in 2014, he did not lead the Republican Conference into a government shutdown showdown, but was dragged into the fight reluctantly. In his words, “When I looked up, I saw my colleagues going this way. And you learn that a leader without followers is simply a man taking a walk.”

This paradox in which we have stronger party leaders who remain weak is a significant source of Congress’s dysfunction. Americans are led to believe that party leadership is the cause of gridlock and polarization, but leaders are more frequently led into political conflict rather than the cause of it. The centrifugal forces that characterized the textbook Congress—independent and autonomous members, responding to their own constituencies rather than to their party leaders—are still present. We think that the centripetal forces of centralized leaders are more powerful in offsetting these forces than they actually are. Members are increasingly pulled in both directions—toward national constituencies reflected in national parties and national politics, and toward the local interests and constituencies they still serve as the source of their authority. Congress cannot remain divided against itself if it is to hold the public’s confidence.

Madison vs. Wilson

But which direction to go? Two chapters in Is Congress Broken?, one by editors Connelly and Pitney and one by the Hewlett Foundation’s Daniel Stid, frame that question as a contest between James Madison and Woodrow Wilson. The editors of the book write that contemporary criticism of Congress is too rooted in a Wilsonian disposition in favor of rapid, unified government action rather than slow, deliberate legislation under a system of divided powers. Connelly and Pitney “seek to revive a more traditional Madisonian perspective on Congress,” one which defends partisan conflict and friction in the legislative branch. “By Madisonian standards,” they argue, “there is nothing inherently wrong with strong opinions and strong words,” such as those which characterize our polarized Congress today. The key is to attach members’ interests to their office, encouraging them to engage in serious deliberation, careful legislation, and effective oversight—not to place partisanship over institutional attachment. “We need Madisonian republican reforms,” the editors conclude, “not Wilsonian democratic reforms.”

Stid sees the two paths available to Congress in the same terms. He draws from two important reports generated by the American Political Science Association (APSA) in the middle of the 20th century. The first, focusing on Congress, argued for expanding Congress’s institutional capacity to oversee and govern the complex modern state it had created. It advocated investing in more congressional staff and strengthening the committees to engage in oversight. As Stid explains, this report emphasized that “Congress was an autonomous branch of government that needed to preserve and enhance its primary constitutional function of deliberation” by investing in itself.

The other report—APSA’s famous defense of “responsible party government”—called for a more parliamentary-style Congress governed by party leadership that bridged the divide between House, Senate, and president. Such a system would enhance government responsiveness by giving voters a clear choice between candidates from two distinct and internally consistent parties. Presumably, voters would cast ballots for individual candidates, based mainly on their party affiliation rather than their individual merit. Such a system would provide collective responsibility; voters would tend to choose consistently one party or the other, rather than splitting their tickets, and, thus, it would be more likely for one party or the other to control all branches of the government. That party would then rely on its leaders to enact the agenda it offered during the election.

Stid argues that “[i]f James Madison served as the intellectual forebear for the Committee on Congress, then Woodrow Wilson did so for the Committee on Political Parties.” The contributors to Is Congress Broken?, therefore, set up a contrast between the Madisonian legislature and the Wilsonian. The former embraces the checks and balances which often appear to produce gridlock as necessary to produce deliberation and to limit majority will in a pluralistic society. The latter, by contrast, seeks to make the legislature an agent of the national majority and to facilitate action rather than inhibit it. Like Connelly and Pitney, Stid prefers the Madisonian option. We should work “with the grain of our system by developing the capacity for deliberation, negotiation, and compromise in Congress,” rather than working against it by introducing parliamentary-style reforms.

The Storm before Reform

It is certainly true that the calls for responsible party government are easily traced back to the thought of Woodrow Wilson. But is the fragmented, disjointed, and gridlocked Congress truly the Madisonian alternative? Madison, after all, was among the first organizers of America’s two-party system, and as a member of the House of Representatives he contributed to the rise of party unity in Congress from the very beginning. One of his mentors, Thomas Jefferson, relied on party unity to bridge the divide between Congress and the presidency during his administration, even going so far as to send bills over to Congress to be passed by his allies. The call for a more responsive system has significant roots in Madisonian republicanism as well as Wilsonian democracy.

Congress today follows neither the responsible party government model, with party leaders using majoritarian institutions to rapidly translate election results into law, nor the model of independent lawmakers who simply reflect the local constituencies that send them to D.C. Congressional elections have become more nationalized, and parties have become more homogeneous, as Congress scholars correctly note. But paradoxically, those developments have not given us strong party leadership or deep party loyalty. Instead, Congress finds itself between these two models, neither entrusting power to its leaders nor decentralizing power to its members.

Major changes in the way Congress conducts business seem inevitable. Historically, every period of congressional reform has been preceded by a lengthy decline in Congress’s effectiveness and popularity. In 1910, party leadership was overthrown because it had become too powerful and the American people (spurred by Progressive reformers) revolted against political parties. In 1946, committee government was established because Congress had become irrelevant, unable to oversee the vast bureaucracy created during the New Deal. In the 1970s, committee chairs were overthrown because they had accumulated too much power and younger, more liberal Democrats wanted more of the action.

In each of those periods, reformers knew what the problem was and how it needed to be fixed. Congress today has reached an ebb similar to those it experienced before. But as the scholarship on Congress attests, we still don’t agree on whom we need to overthrow and whom we need to empower.