Books discussed in this essay:

Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace

The Pale King, by David Foster Wallace

Elegant Complexity: A Study of David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest, by Greg Carlisle

The Legacy of David Foster Wallace: Critical and Creative Assessments, edited by Lee Konstantinou and Samuel Cohen

Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace, by David Lipsky

The Unfinished: David Foster Wallace's Struggle to Surpass "Infinite Jest", by D.T. Max

The Broom of the System, by David Foster Wallace

Girl with Curious Hair, by David Foster Wallace

A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments, by David Foster Wallace

Consider the Lobster: And Other Essays, by David Foster Wallace

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, by David Foster Wallace

Oblivion, by David Foster Wallace

Everything and More: A Compact History of Infinity, by David Foster Wallace

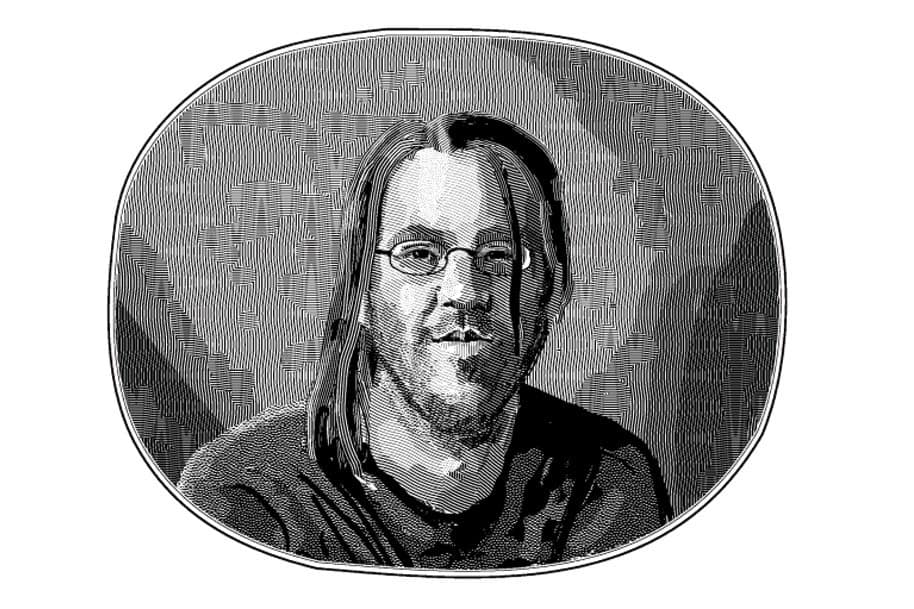

Just about everyone who pays any attention at all to contemporary fiction knows two things about David Foster Wallace (1962-2008): he wrote a thousand-page novel with hundreds of end-notes that launched him as a cult hero, and he killed himself while still quite a young man. The novel, Infinite Jest (1996), his second, and the last one he completed, has established Wallace as a supreme postmodernist master, revered like John Barth or Thomas Pynchon by those who take a passionate interest in that kind of thing. The suicide for its part enhanced the mystique, as suicides of distinguished artists almost invariably do.

Wallace may be dead but he is not finished, or rather the Wallace industry is not finished with him. His 2005 commencement address at Kenyon College has appeared posthumously in a book of postcard dimensions, with one sentence per page, a format more suited to the lucubrations of Khalil Gibran or Rod McKuen. Columbia University Press has issued Wallace's undergraduate philosophy thesis in a volume with his name above the title and his photograph on the cover, although his essay actually occupies 75 pages of a 262-page book, the rest filled with pieces by assorted other hands on similar topics. The torso of an unfinished novel, The Pale King, appeared last year. A volume of unpublished stories and another of uncollected journalism look to be on the horizon; two volumes of letters are in prospect as well.

Encomia soar ever higher with the passing of time; every admirer feels obliged to surpass every other admirer in the length, breadth, and depth of his admiration. James Ryerson, an elegant and judicious journalist, mourns the loss of contemporary American fiction's "most intellectually ambitious writer." Greg Carlisle, an actor and drama professor from Kentucky who spent five years producing a 500-page commentary on Infinite Jest, calls Wallace "the best and most important author of the late 20th and early 21st centuries"; one supposes Wallace had better be at least that important, if the professor is to justify devoting five years of work to criticism of a single novel. An even headier enthusiast, Jon Baskin, claims nothing less than world-historical significance for his hero:

It became a commonplace and then a cliché and then almost a taunt to call him the greatest writer of his generation, yet his project remained only vaguely understood when it was understood at all. With the benefit of time, it will be recognized that Wallace had less in common with Eggers and Franzen than he did with Dostoevsky and Joyce.

Jonathan Franzen, who was tight with Wallace, will be joining Don DeLillo and others in a collection of memorial essays from the University of Iowa Press; the praise will doubtless flow profusely, although, novelists being what they are, comparisons to Dostoevsky and Joyce will likely be in short supply, such honorifics generally reserved in celebrated writers' minds for themselves alone. Franzen has spoken of an asymmetrical rivalry in his friendship with Wallace. Wallace got the "cult credibility" and academic regard, while Franzen got wider fame and more money—which is to say, though Franzen does not say it, the imprimatur of Oprah's Book Club. Franzen allows that while he felt the rivalry, perhaps Wallace did not. Which is to say, though Franzen does not say it, that Wallace was a better man than he.

The Kid Had Something

What sort of man was Wallace? How did he live, how did he want to live, and why did he die the way he did? What were his intellectual and artistic preoccupations, indeed obsessions? Was he the singular genius his perfervid admirers make him out to be: the Dostoevsky of our time and place? Without a full-dress biography available, one can only make a stab at these questions at this point. But Wallace seems significant enough that one ought to make a stab. (For the facts of Wallace's life I rely chiefly on Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace(2010), a 352-page edited transcript of interviews conducted over several days in 1996 by the Rolling Stone journalist David Lipsky, and the long New Yorker article "The Unfinished" (March 9, 2009), by D.T. Max, who is working on a Wallace biography.)

David Foster Wallace was born in 1962 in Ithaca, New York, where his father, James, was a philosophy graduate student, under the direction of Norman Malcolm, who had been a Wittgenstein acolyte at the University of Cambridge. James would soon get a teaching post at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and David would grow up a Midwestern boy.

Like all robust Midwestern boys, he was inclined to raise a little hell, but he was mostly inclined to win good grades and tennis trophies. Bookishness, and thoughtfulness, were encouraged in the Wallace household, to say the least. James read Moby-Dick aloud, every last word, including the cetology stuff, to the five-year-old boy and his three-year-old sister. The procedure likely did no lasting harm. At fourteen David asked his father to initiate him into certain philosophical arcana, and James goggled at his son's adroit and probing mind.

The boy was also a hot-shot jock, good at football, especially good at tennis, becoming a regionally ranked junior player, though the more adept kids from the Chicago suburbs would hose him pretty much every time. He lacked the local hot-shot's confident swagger, however: during his senior year of high school, anxiety attacks off court would leave him soaked with sweat, so that he carried a towel around to wipe himself down, along with his tennis racquet, to make the towel appear a sporting accoutrement. The anxiety caused the youth deep shame, his father remembered.

Academic success and emotional trouble followed Wallace to Amherst College. Teachers recall him as a student of Stakhanovite determination and industry. Mathematics and philosophy, especially modal logic and Wittgenstein, allured him. But he cracked during his second year, and headed back home, consulting a psychiatrist, going on antidepressants, working for a spell as a school bus driver. A career in academic philosophy was the wrong fit for him, he realized, however everyone else might think he was made for it. He would tell an interviewer in 1990, "I had kind of a midlife crisis at twenty, which probably doesn't augur well for my longevity."

Back at Amherst, he started to read a lot of fiction, with Pynchon and DeLillo particular favorites, and to write with fire in his belly. Not only did he produce a prize-winning philosophy honors thesis taking apart a well-known essay on fatalism (the belief that what you do in the present does not affect the future, a fallacy Wallace showed to be a confusion of semantics with metaphysics), he wrote a long novel as his English honors thesis, The Broom of the System. The novel would be published in 1987. Philosophy serves as the armature of the novel, though there is no shortage of the customary postmodern whimsy: characters with funny names; a food additive that speeds up infant learning exponentially and reverses senile degeneration; a talking cockatiel that becomes, under the influence of the additive, a Christian television prophetic celebrity; nursing home patients who disappear en masse, among them the heroine's grandmother, who studied with Wittgenstein and proselytizes for the belief that language constitutes reality. Wallace would describe the novel later as a contest between Wittgenstein and Derrida concerning the nature of the real world, and would say there were quite a few people who liked it but most of them were eleven years old. Even for a reader considerably older, the novel has its amusements, but the philosophic seriousness that Wallace's biggest fans love to find everywhere in his work is negligible. Still, it was clear that the kid had something.

Dead Ends

For some time now young writers have been serving their apprenticeships in creative writing programs, and Wallace took the conventional academic route and did an M.F.A. at the University of Arizona. Sadly, he produced ever more conventional academic fiction while he was there, putting the finishing touches on Broom and writing the short stories that would appear in Girl with Curious Hair (1989). It was grad school, but the stories were sophomoric. The title piece, dedicated to William F. Buckley and Norman O. Brown, depicts a night out on the town for the yuppie lawyer sexual psychopath narrator (he burns the numerous women who fellate him, presumably because years ago his father, a Marine Corps general, scorched his son's penis with a lighter when he caught the eight-year-old boy looking at porn and imitating what he saw with his ten-year-old sister) and his punk rocker companions, whose repulsive vacuity suits him right down to the ground. Behind the façade of Ivy League blue blazer respectability, maggoty horror pullulates, and that goes double if your dad is top military brass, or if you admire William F. Buckley. The story is sickeningly stupid and puerile. Other celebrated stories, one about an actress who scores the unimaginable coup of one-upping the ironist's ironist David Letterman, another about the reunion of all the actors who ever appeared in McDonald's commercials and overly elaborate play with John Barth's canonical story "Lost in the Funhouse," may not be sickening but sure are puerile, in the hippest and most advanced fashion, of course. Wallace had proceeded headlong into a dead end.

Once again, psychologically he crashed and burned. He spent a despondent several months teaching at Amherst, then returned to Arizona, where the despondency turned to desperation. From Tucson he called his parents to say he was thinking of doing something dreadful to himself; his mother came and got him. A tear-jerking TV movie and his sister's having to leave home for school provoked him to take an overdose of pills. Hospitalization and electroshock followed. The drastic treatment restored him, sort of. He became convinced writing fiction endangered his sanity. Back to philosophy, then, which offered ecstasies of its own, as well as the reassurances of reason.

Grad school at Harvard broke him down in a hurry. He had always done drugs. In high school he had dropped a lot of acid, and it had affected him badly, and permanently, he feared. At Amherst he had smoked pot, but had been too much the swot to let recreational puffing interfere with his work. Now he cut loose, inhaling marijuana regularly, snorting a little cocaine, trying some psilocybin, even smoking black tar heroin once, and realizing the pleasure it gave could be the end of him. He also became something of a barfly, guzzling beer and picking up stray women—too much beer, too many women. He came to understand that he was in serious trouble.

A stint at McLean Hospital, a new course of the drug Nardil, and a spell in a halfway house changed him gradually. He took on his drug and alcohol addictions in earnest, joining in rehab sessions with the sort of people he had never hung out with before: as he wrote to his editor, "Mr. Howard, everyone here has a tattoo or a criminal record or both!" The new company he kept, and the effort to straighten out his life through the regimen of Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, transformed him as man and writer. The brainy dazzlement of Derrida and his ilk, the beguiling rarefactions of fashionable intellect, had gotten him nowhere: worse than nowhere—they had landed him in hell. He wanted out, and the comradeship of fellow sufferers with the same yearning for psychic health helped give him strength. The A.A. mantras that supposedly serious persons find so trite and ludicrous—One Day at a Time was the name of a sitcom after all—held truths he needed. Reiterated common sense aphorisms worked better for a desperado like him than renowned profundities, or pseudo-profundities.

Pain

He had lived for recognition and sensual pleasure; he had figured in the American entertainment culture as both producer and consumer; and he had scraped bottom. Seriousness, indeed salvation, lay along another road. In 1991 he began writing Infinite Jest, his intended summa on the national compulsion for diversion unto death. The book would engage all his powers as no previous work of his had done. Wallace was writing for his life, and for the lives of his countrymen. The matter was as grave as that.

The fundamental human experience in this novel is pain-physical, mental, emotional, contrived by the powers so that it is never quite the same for any two persons but also so that most everyone (there is one possible exception) gets rather more than he could ever want. The very word pain rings throughout the novel the way virtue does in Machiavelli or real in Proust or good in Hemingway. Seeking pain, killing pain, using pain, surviving pain are some of the variations on the theme. There are certain peculiarly American aspects to this general torment: modern democratic life features tortures less spectacular but no less intense than the sufferings of Job or the fires of the autos-da-fé. (Wallace was writing during an interlude of peace.) Of course we have analgesics and anesthetics and we don't burn heretics. Compassion is the pre-eminent democratic virtue, and many of us feel the suffering not only of our fellow human beings but of animals that we hesitate to dismiss as dumb beasts. Enormities have not vanished from our tender-hearted republic, however; quite the contrary. Psychic distress abounds. People want the wrong things, or want good things in the wrong way. Desires all too readily become addictions. Antidepressants are the most commonly prescribed medications in America. Our sensitivity to pain has prompted us to do all we can to eliminate it, but we are ever more vulnerable to the pain we cannot root out. And there will always be human monsters, who take pleasure in the pain of others, who transmit misery from generation to generation, who infect whatever they touch.

This is the world that Wallace knows as well as anyone. The plot-lines sprawl around an addicts' halfway house and a tennis academy for elite young players, both in a Boston suburb in 2009, the Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment, in the new era of Subsidized Time. Although one place is a refuge for obvious failures and the other a launching site for the enviably gifted, some bound perhaps for stardom, both places are rife with the endemic American pathology: the longing to avoid the unavoidable pains of living, to blur the hard edges of reality. Certified social rejects and hot prospects alike tend to be sad and desperate characters. Most of the best tennis players take small joy in the game itself, the activity for its own sake; they drive themselves with dreams of making it big, so that they can enjoy the boffo celebrity orgy one day. To be a rich and famous entertainer is the ultimate good in their eyes; it is what every American aspires to, after all. There can be grace, in every sense of the word, in practicing a demanding sport at a high level; to strive for grace in the highest sense is far beyond these young and talented yahoos. A lot of the kids get loaded on a regular basis; one shrewd student entrepreneur does a booming business in clean urine for drug tests.

The prime athletes don't know how good they've got it. Some other people never stand a chance. A young woman who is addicted to marijuana and has barely survived a suicide attempt tries to explain to a doctor what depression is. "It's like horror more than sadness. It's more like horror." Depression is the pain that won't quit, emanating from who knows where, as though you awakened to find a torrent of black widow spiders advancing up your torso toward your face. To feel nothing, the woman avers, would be better than this. A magna cum laude graduate of Brown who is now a halfway house resident describes a vision of a "black flapping shape" that embodied pure evil in his eyes and threatened to ruin him for good: "It was total psychic horror: death, decay, dissolution, cold empty black malevolent lonely voided space. It was the worse thing I have ever confronted." Pain of this order isolates the sufferer. To be utterly alone, incapable of touching or being touched, is the agony of the depressive. It is the agony of almost everyone in the novel, to some degree.

Depression and the desire for oblivion may be natural enough responses to a world as foul as the one Wallace portrays, which is the actual world, terrifying enough in itself, made grotesque and even more terrifying by magnification. The spectacle is a real horror show. An intellectual prodigy, tennis ace, and inveterate drug user loses the ability to make his thoughts intelligible, and disintegrates into bestial thrashing and grunting at a college interview; his father kills himself by placing his head into a microwave oven; a woman kills herself by plunging her arms into a garbage disposal; a cocaine fiend and halfway house resident swings stray cats against telephone poles and slits the throats of neighbors' pet dogs; a woman in a street fight leaves her stiletto heel stuck in a dead man's eye; a drug dealer sews open the eyelids of a Dilaudid freak who stole from him, so the transgressor won't miss a moment of the dealer's revenge. Each instance of savagery outdoes the previous. Wallace recites an endless litany of the perverted and reprehensible, as though he were invoking the innumerable names of the devil.

That is not to say he doesn't sometimes find the perversity funny, in a diseased way. A late night M.I.T. radio host called Madame Psychosis summons nature's unfortunates to take the veil of U.H.I.D., the Union of the Hideously and Improbably Deformed. "All ye peronic or teratoidal. The phrenologically malformed. The suppuratively lesioned. The endocrinologically malodorous of whatever ilk. Run don't walk on down. The acervulus-nosed. The radically -ectomied." Madame Psychosis turns out to be the erstwhile PGOAT, or Prettiest Girl of All Time, who was accidentally disfigured by acid thrown in a fit of insanity by her mother (the garbage disposal suicide), and who became the muse of an avant-garde film-maker (the microwave man). She starred in the underground video Infinite Jest, naked, pregnant, her body impossibly lovely, her face discreetly airbrushed: the living representation of sex, beauty, tenderness, fecundity, and more; Angelina, Mom, and Death. For the video offers lethal bliss: anyone who watches it once will watch it over and over again without pause, forgetting everything else, and inevitably dying of the ecstatic overload.

Pascal wrote of the human need for diversion: to think of God, death, the silence of infinite space was more than men could bear. Wallace shows modern men so desperate for diversion that they use it not to avoid death but to pursue it. After all, they fear nothing that death might hold, for they are sure it holds nothing. Pleasure here and now, so real, so overwhelming, such a relief from pervasive pain, is everything you could want. Ordinary living is not worth the trouble when there exists a way out as rapturous as this. The perfect entertainment.

Moral Beauty

What hope then does Wallace offer? Against the world's inhuman cruelty, the pointless wreckage of addiction, and the wasting mindlessness of the entertainment culture, he opposes pain that has a plan and a purpose. That is the pain of sobriety, of seeing clearly, of understanding why you ever needed to anesthetize yourself: "…the way it gets better and you get better is through pain. Not around pain, or in spite of it." It is a teaching only the strong can live by; those who are not strong enough are in serious danger of going down. We are a nation of addicts, Wallace insists, in a chronic state of denial, craving the wrong kinds of pleasure and undone by the wrong kinds of pain. Purification is called for. By no means, however, does Wallace condemn all activity that is not undertaken purely for its own sake; that would be to condemn almost everything people do. What he does condemn is gross self-seeking ambition that cares only for the prizes and the gleam of envy in others' eyes. In the absence of a genuine calling, which does not exclude honest ambition, whether one happens to be a lawyer or a businessman or an athlete or a writer, success is a corrosive illusion. Wallace updates Tolstoy, who labored all his life against the insidious collusion of sensuality and amour-propre. To live unseduced by media sirens or the longing for celebrity or fatuous simulacra of love or the urge for simple obliteration is the aim Wallace sets for the reader; it is the aim he set for himself as a recovering addict and mental patient and as a writer serious as he had never been before. However the world might have damaged you or you have damaged yourself, however you might believe you need your substance or fantasy of choice to make it through the day, resistance and integrity and moral beauty remain possible.

Two exemplars of moral beauty stand out; both are damaged and strange. Don Gately, who is a former high school football stud, a recovering Demerol addict, and a resident supervisor at the halfway house, leaps into the middle of the brawl when a gang of men enraged by the butchery of their dog come looking to kill anyone associated with the addicts' haven. Gately fights like a hero, and like the thug he once was, but he is shot in the shoulder. Hospitalized, the agony of his wound aggravated by toxemia, Gately refuses pain medication, determined to stay perfectly clean and sober even as the doctors pressure him to see reason and take the drugs. The closing pages of the novel, in which Gately recalls his last high, contain some of the strongest and most horrifying writing in 20th-century American fiction.

The other moral hero is different as can be from Gately: Mario Incandenza, fourteen years old, crippled every which way and not quite right in the head, yet possessed of an effulgent innocence, though he is not a sainted cartoon character but a living boy of genuine charm. Two brothers engage in a bet on whether humanity is beyond redemption; Wallace overtly likens their dispute to that between Ivan and Alyosha Karamazov. The optimistic brother stands for days on a busy street corner, dressed as a typical urban waste product, and entreats passersby simply to touch him. No one does, until Mario happens along and takes his hand affectionately in his own without a second thought. Wallace does not overplay the moment, and it is one of surpassing loveliness, all the more so for Wallace's habitual concentration on the hideous and degenerate.

Infinite Jest is a novel abundant in felt life and hard-earned wisdom. One must admit it is also abundant in studied bizarrerie and rampaging ugliness. Not every reader can get past them. While the themes in the abstract take after Tolstoy, the execution goes far beyond even Dostoevsky in its obsession with the twisted and downright macabre. Perhaps this is as fine a novel as someone who suffered so grievous a psychic mauling as Wallace did (and who does not happen to be Dostoevsky) can write. That is a severe qualification, but it is not meant to be a condescending one. Wallace issues a stirring call to normality precisely because he knows what moral sickness is, from the inside. He knows the worst about American soullessness, yet offers hope that the most far-gone sufferers, among whom he numbers many who pass for normal, can recover their souls. Infinite Jest is a work of impressive moral amplitude, taking in more of modern American reality than the novels of most of the recent acknowledged realist masters. With this novel alone, Wallace will long outlive Mailer, Cheever, Updike, Styron, Roth, not to mention Eggers and Franzen.

Too Much to Endure

Wallace never completed another novel. He excelled at journalism, from a point of view mostly liberal but contemptuous of political correctness, writing celebrated pieces, some of them many miles long, on such subjects as the Illinois State Fair, television and American fiction, the film-maker David Lynch's obsession with evil, a week misspent on a Caribbean cruise ship, the pornography industry, the social implications of prescriptive as against descriptive grammar and usage, the inability of great athletes to describe their physical genius, John McCain's extraordinary heroism in Vietnam and his conduct on the 2000 campaign trail, conservative talk radio, Dostoevsky's seriousness as antidote to postmodernist monkeyshines, and the ambivalence of a man who enjoys the taste of animal flesh toward boiling lobsters alive. These and other essays, nearly all notable for the sadness and unease that cut against their energy and wit, are gathered in A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again (1997) and Consider the Lobster and Other Essays (2005). He continued to write short stories, chiefly on the themes of depression, emotional fraudulence, loneliness, suicide, and double binds; these were collected in Brief Interviews with Hideous Men (1999), which was made into a movie that he rather liked, and Oblivion (2004). He also turned out a learned and difficult book about esoteric mathematics called Everything and More: A Compact History of Infinity (2003).

Now Little, Brown has published a 547-page fragment of the novel Wallace was working on at the time of his death, The Pale King, which takes for its subject life at the Internal Revenue Service; transcending the boredom and numbness of inescapable routine through intense mindfulness is his principal concern here. Even pencil-necked geeks at the most loathed agency in the American government can prove to be heroic; to work with no expectation of applause but strictly for your own satisfaction in doing a stultifying task competently is the essence of virtue in bureaucratic modernity. As an accounting professor tells his class: "Here is the truth—actual heroism receives no ovation, entertains no one. No one queues up to see it. No one is interested." There is bracing realism in that, but surely Wallace is promoting, and his book is embodying, a doctrine too austere for a form such as the novel. Novels have traditionally interested and entertained their readers; one might say they are supposed to. To deny them these qualities is an innovation one can do without. Long stretches of verbatim IRS regulations induce not heightened awareness but a quick flip of the page to avert coma. One may appreciate the devotion of Wallace's IRS agents at their best yet want no part of enduring as a reader the tedium they must endure in their duties. There are some fine passages in this book, but the whole is interesting only as a document of Wallace's preoccupations as the end was approaching.

It was not boredom that killed him, however. It was the depressive's despair at pain that appeared to have no possible end except in death. Wallace had been taking Nardil for his depression since 1989. Nardil is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, or MAOI, a member of the earliest generation of antidepressants; newer drugs are usually not only more effective against the illness but also less likely to cause collateral damage. In 2007 Wallace was a happy man, writing, married since 2004, for the first time, to the artist Karen Green, and teaching at Pomona College, one of the distinguished Claremont Colleges, where he had an endowed professorial chair that gave him pretty much free rein. After dinner at a Persian restaurant in Claremont one evening, he developed excruciating stomach pains that lasted several days. His doctor suspected a dire food interaction with Nardil, and suggested Wallace go off that outdated medication and try something newer. Wallace had already suspected for several months that Nardil was impeding the flow of The Pale King—though it evidently had not interfered with Infinite Jest—so the idea sounded promising. But then Wallace tried doing without any medication at all, and he landed in the hospital in the fall of 2007. After that he went on one drug after another but never really gave any of them the chance to be effective. Not wanting to foul his home, he tried suicide by overdose in a nearby motel, but survived. A course of twelve electroconvulsive treatments failed to work. He went back on Nardil; it did not kick in quickly enough. Not caring any more what he fouled, on September 12, 2008, he waited for his wife to leave for her gallery, wrote her a two-page note, and hanged himself on the patio of their Claremont home. He left a neat stack of manuscript pages in his garage office for his wife to find.

David Foster Wallace's suicide was the greatest literary tragedy since John Berryman flung himself from a Minneapolis bridge in 1972. The pain of mental illness and drug addiction constituted a frightful part of who he was. Out of that pain and his efforts to purify and to heal himself he wrote one of the most remarkable novels of our time. To say it reaches the heights of Joyce or Dostoevsky is going too far, but it will stand, and it has something crucial to teach generations of readers about how to live, even with terrible pain they might think they cannot endure.