Book Reviewed

This summer, the news cycle was briefly exercised by the decision of a U.S. Olympic hammer-thrower to turn her back on the American flag during the national anthem, before unfurling a t-shirt emblazoned with the words, “Activist Athlete.” In the historical profession we’ve been used to this kind of thing for some time, with new publications taking the place of protest t-shirts. This garners less attention than in the world of sports but is surely a more significant development. Being an activist athlete, after all, should not necessarily make you a worse thrower of hammers, discuses, shotputs, or anything else. But being an “activist historian” emphatically does seem to make you a worse historian. At least, this must be the inevitable conclusion to be drawn from one of the latest books to emerge from the Stanford University history faculty.

Priya Satia’s Time’s Monster: How History Makes History would not normally merit coverage in a magazine intended for those who enjoy reading the latest works of history and political thought. Indeed, even if one were wholly sympathetic with the book’s polemical aims, it would still be difficult to recommend that people read it, in light of its stream-of-consciousness style of composition and emetic prose. But Time’s Monster has captured the spirit of our present moment: on both sides of the Atlantic, the book—which claims to uncover the “collusion” between the discipline of history and empire—has been embraced as part of a broader street-renaming and statue-toppling social movement. As such, it is worth closer study—for what it reveals about the intellectual groundwork of this moment, but also for the light it shines on the kinds of cutting-edge historical scholarship produced at the height of the American academy. In both respects, the picture is discouraging.

* * *

The logical chain at the center of Time’s Monster is captivatingly simple. Britain’s empire, Satia writes, was inhumanity itself—this has been “proven” by “countless anti-colonial thinkers and historians.” To make it endure as long as it did, Britain’s “national conscience” needed constant assuaging so that otherwise good and well-meaning Brits could partake in its evil. The discipline of history and the “historical sensibility” that emerged out of the Enlightenment, by providing publics an alternative system of ethics to the demands of regular human feeling, were essential to successful empire building. By way of illustration, Satia presents Samuel Galton, an 18th-century Birmingham Quaker and gunmaker central to her last book, Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution (2018). Around 1790 Galton was arraigned before a group of fellow Quakers and called upon to explain how he squared his pacifist religious commitments with his role as one of the biggest suppliers of weapons for Britain’s wars. He responded by claiming that, in the historical moment in which they had been placed “by Providence,” they had no choice but to participate in Britain’s war economy. In short, Satia explains, Galton appealed to the “philosophical authority of the emerging historical discipline” to justify conduct his conscience told him was immoral.

British imperialism’s self-justifications—its “historical scripts”—took many forms at different times over the empire’s long life. The most important was liberalism with its conceptions of progress and civilization. Others included Romantic, social Darwinist, Biblical, and even “Mystical-Occult” frameworks. All purportedly justified present immorality by reference to future (or past) imperatives. Satia writes that history continued to be the handmaiden of imperialism, racism, and state violence right up to the 1970s—when new ideas about class, race, and gender decolonized the discipline and made it an activist critic of power. Yet imperialist historians still practice today, and the discipline has failed to “fully confront its past”—which is why the British empire is still not included alongside “other modern crimes against humanity, such as the Holocaust and Hiroshima.”

* * *

How compelling is Time’s Monster’s claim that historians have been “the key architects of empire”? The assertation depends very much on the definition of “historian.” But Satia never bothers to provide one. Many will doubtless be surprised to discover that a book purporting to uncover the relationship between history and empire has as its main subject neither the historical discipline nor, for the most part, historians. We are offered instead a tired run-through of around a dozen all-too-familiar author-statesmen connected to Britain’s empire: from Thomas Macaulay, James and John Stuart Mill, through to Winston Churchill, most of whom are reduced to little more than a selection of their most boorish and clichéd quotations. We can all agree that Thomas Carlyle probably fits the bill. But why does amateur archaeologist and celebrity memoirist T.E. Lawrence form the basis of a whole chapter, when titans among historians—from William Stubbs to J.A. Froude to G.M. Trevelyan to R.G. Collingwood—do not get so much as a mention? Well, because Lawrence was a “key architect of empire”—and presumably therefore a historian (and so on). Very quickly, Time’s Monster becomes an extended exercise in tautology.

To speak of historical discourses or “scripts” allows one to sidestep such issues as the need for precision or accuracy. But what constitutes “historical thinking” in Satia’s view teeters on the absurd. A politician making a speech about a “historic act” or claiming to “make history” is enough to justify all kinds of extravagant deductions about how “history” made history. Almost anyone explaining anything with reference to such commonplace human sentiments as self-doubt, regret, or rationalization—in a single private letter or diary entry—becomes roped into the grandiose story. Yet on the few occasions Satia does pronounce on actual historical scholarship, she seems remarkably blasé about the rules of evidence. A sweeping condemnation of the immorality of “histories published in the 1880s” about the Indian Mutiny of 1857 is supported with reference to one history, cited in a book by another author. Satia writes that it was axiomatic, in the “dominant British point of view,” that this uprising was the product of Indians’ irrational fanaticism rather than any legitimate political grievance against colonial rule. Yet the entire gist of the semi-official British history of that episode (reissued in six volumes in the 1880s, no less) is to condemn Britain’s colonial policy for causing the rebellion, and goes so far as to praise some of its Indian rebel leaders as “true patriots” fighting for their “wrongfully destroyed independence,” whose memory was “entitled to the respect of the brave and true-hearted of all nations.” This is less discourse analysis than disinformation.

* * *

The problem with such carelessness over one’s subject-matter is that it becomes difficult to show how one thing caused another—that history, for example, made empire. This is not too much of an issue in Time’s Monster since Satia tends to rely on metaphor to make her case: historical thinking forms a “backdrop” for empire; it “underwrite[s]” imperialism; it makes up part of the (brace yourself) “intellectual swirl.” The book’s only attempt at the kind of close study necessary to demonstrate cause and effect is of British aerial bombing of rebellious Arabs in the 1920s and ’30s. This policy was highly controversial at the time, and the various arguments advanced over it—including an aversion to “boots on the ground,” imperial overstretch, difficult geography, and pressure from local allies—are well known. Yet here is Time’s Monster’s considered case for why history, particularly the mystical-occult “historical script,” was the true cause:

Experts claiming oracular insight into the region insisted that aerial control was the best midwife of the region’s historical progress: In a land trapped in biblical, medieval, and mythical time, and subject to the machinations of malevolent occult forces, its modern reinvention of destruction wreaked from heaven by British knights in the sky made a unique sort of sense.

Readers will no doubt wish to draw their own conclusions—on the matter of causes, and on just how much of this kind of drivel they can stomach.

These are mere second-order problems, however, alongside Time’s Monster’s obviously faulty premise—that people needed history to support war or empire. Frequently, all such support required was common sense. The moral dilemma faced by the Quaker Samuel Galton cannot, as Satia implies, be generalized to the wider British public. Even if it could, the experiences of those defeated or occupied by Napoleonic France, in the Rhineland, Spain, or northern Italy, would suggest to any Briton that his most basic interest required support for Britain’s global war machine. As for the empire, this operated day-to-day through such a patchwork of colonial constitutions, locally-made political bargains, treaties and trade-offs, inherited patterns of collaboration and even consent, aside from acts of imperial violence, that it did not normally require any elaborate historical justification. In any case, the very idea that Britons needed their consciences assuaged so that—in a world dominated by empires—they could be brought to support Britain’s, is the most elementary of anachronisms. It is not even clear that there is a historical problem here in need of resolution.

* * *

But Time’s Monster has been embraced less for its scholarship than for its “call for action” at a moment when the Western world is experiencing a broader reckoning about legacies of slavery and imperialism. In Britain the need to “dismantle the narratives that underpinned empire” is supposed to be particularly acute, since polls suggest that a minority of Britons—but at over 40%, apparently too large a minority—still believe their empire did more good than harm in its colonies. Time’s Monster has been praised as an unequaled handbook in the parallel struggle within the academy to “decolonize knowledge” and “reimagine” the writing of national histories for the future.

It is as a policy handbook, however, that Time’s Monster gets really alarming. In a chapter titled “The Past and Future of History,” Satia outlines what the “struggle for justice” in British historiography must involve. In essence, it requires comparing your opponents to the Nazis. Historians who assess the institutional legacies of British colonialism against the record of its sins are likened to those who would dismiss the Holocaust in order to praise Hitler’s building of the autobahns; historians offering romantic or nostalgic views about the imperial past are likened to full-blown “Holocaust deniers” and those who would embrace “the Confederacy in the American South and the revival of Nazi sentiment in the United States and Europe.” Satia’s explicitly identified goal is to end debate over the British empire—because, we are told, the very existence of continuing historical debate is “evidence of empire’s continuing presence.” This proscription does not just extend to those seeking to weigh imperial “pros and cons,” but even to those engaged in basically antiquarian revisionist scholarship about 18th-century British governors of India, who are named and shamed as if they were purveyors of extremist content.

But there’s more. One of Satia’s bugbears is that academic historians are unable to monopolize the public conversation over national histories. Instead, their works “flow into a vast lake of historical production,” alongside contributions from “popular historians, museums, novels, films, TV dramas, activists, and countless members of the public.” She quotes the slogan of the Party in George Orwell’s 1984—“those who control the past control the future” and “those who control the present control the past”—but less as a warning to the public than to professional historians, who must do a better job of controlling popular thought. It is a moment of brief comic relief in a book short on laughs—one made more amusing by the fact that none of the book’s academic reviewers have thought it worthy of note. As Hannah Arendt said of the craze for Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth in the 1960s, one can only hope that no one has actually read Time’s Monster to the end.

* * *

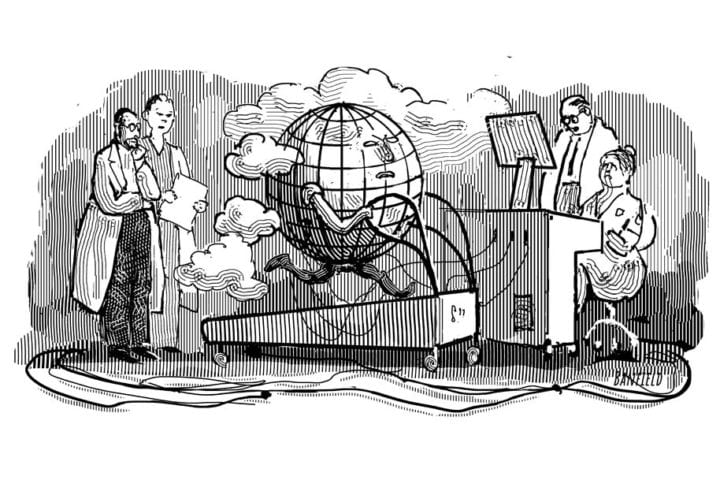

This picture of the current historical professions may engender pessimism. But by curious coincidence the publication of Time’s Monster was followed several months later by another book on an ostensibly similar subject and with an almost identical title. Rosemary Hill’s Time’s Witness: History in the Age of Romanticism offers a panoramic account of the lives and work of two generations of historians, or “antiquarians,” who transformed knowledge and scholarship about Britain’s national past from the 1790s onward. Antiquarians have long been the subject of caricature: pedantic scholarly wool-gatherers compiling obscure dissertations on, for example, the history of trousers in Wales. Yet Hill’s book is a remarkable demonstration of how much the modern historical craft owes to their innovations in methodology and scholarship. The titles of their studies are richly evocative of the genre: The Progresses and Public Processions of Elizabeth I (1788), or A Complete View of the Dress and Habits of the People of England (1796). They include documentary studies of the real historical figures behind the myths that surrounded “great men,” from Robin Hood to William Shakespeare. And almost every one of the largely forgotten scholars brought to life in Time’s Witness has as much claim to be a historian as those featured in Time’s Monster, though beyond Macaulay and Carlyle there is hardly a name in common.

Indeed, one returns from Hill’s exquisite work to Time’s Monster’s crude generalizations open-mouthed. Satia tells us that “[f]rom the era of the Enlightenment through the Suez Crisis, the powerful had claimed the discipline of history for themselves,” and historians “were not hobbyists on the sidelines, but the very makers of history.” Yet from Time’s Witness we discover how for generations history writing offered a haven in British society for the less privileged, for religious minorities, and for women—like Anna Gurney (1795–1857), disabled from a childhood illness, who dedicated her life to mastering ancient Teutonic languages and bringing new texts to bear on the British national story, including making the first modern translation of the Saxon Chronicle and becoming the first female fellow of the British Archaeological Association in 1845; or John Nichols (1745–1826), baker’s son and manager of a London printworks, who self-published his own half-dozen studies of Tudor and Stuart society which even today remain classics in the field; or John Lingard (1771–1851), whose pioneering, eight-volume history of England offered a myth-busting, primary source-based alternative to Macaulay’s, yet was neglected throughout his life because he was a Catholic.

* * *

Time’s Witness is not a political book: it offers no guide to action in the decolonization of knowledge. But for those in need of political models from the past, what could be more apposite than its portrait of Alexandre Lenoir (1761–1839), medieval art enthusiast and museum curator, who at the height of the French Revolution, when the Committee of Public Safety announced that the 800-year-old tombs of the French kings and queens at the Abbey of St.-Denis should be destroyed in celebration of some revolutionary anniversary, descended himself into the catacombs to physically protect the monuments against the baying mobs of statue-toppling iconoclasts?

Time’s Witness is one of the most outstanding “popular history” books released in recent years, filled with originality and shedding fresh historical light on each episode it touches. In every way it is an antidote to the politicized dudgeon of Time’s Monster. Buy it and rejoice that the “vast lake of historical production” is still beyond the control of the historian-activists.