Book Reviewed

Abraham Lincoln delivered versions of a “Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions” in several places in 1858 and 1859. That Lincoln was thinking through the ideas in this lecture during those fateful years is a remarkable revelation of the range of his preoccupations. And he wasn’t finished thinking about them, though he set them aside to attend to some pressing practical matters. As Diana Schaub recounts in a recent essay for the New Atlantis, “The Invention of Slavery”:

Upon heading to Washington to assume the presidency in February 1861…Lincoln bound together two manuscripts of [the] lecture and entrusted them to an acquaintance for safekeeping. Four years later, at the start of his second term, he told a visiting scientist of his intention to put the lecture into final form…“when I get out of this place.”

Lincoln was bound to urgent earthly duties, but as Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Almighty God hath created the mind free,” and no American statesman ever put that freedom to better use than Lincoln. In his lecture, he calls writing “the great invention of the world”; it enables us “to converse with the dead, the absent, and the unborn, at all distances of time and of space.” And the invention of printing, he says, is writing’s “better half.” It marks the end of “the dark ages” by extending the emancipation of the mind to untold numbers of readers, who now have a better chance to realize that they and all men are by nature capable of “rising to equality.”

* * *

Schaub makes clear in her new book, His Greatest Speeches: How Lincoln Moved the Nation, that Lincoln from his earliest days took great pains to put his speeches accurately into writing and print. He meant not only to speak to as many of his contemporary fellow citizens as possible, but to converse with “the unborn, at all distances of time and of space.”

Schaub—a frequent contributor to these pages—is professor of political science at Loyola University Maryland and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. She is herself a master of the art of writing. Her works on every subject are high-minded and full of intelligence, learning, and grace. Her best pieces on Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln are inspired and rise to the sublime. This short book “takes the form of a commentary” on three of Lincoln’s speeches: what is commonly called his Lyceum Address, delivered to the Springfield Young Men’s Lyceum in January 1838, when Lincoln was 28 years old; the Gettysburg Address, delivered 25 years later in 1863, by Lincoln as president in the midst of civil war; and the Second Inaugural Address, delivered on March 4, 1865, just 36 days before the war ended and 41 days before Lincoln was assassinated.

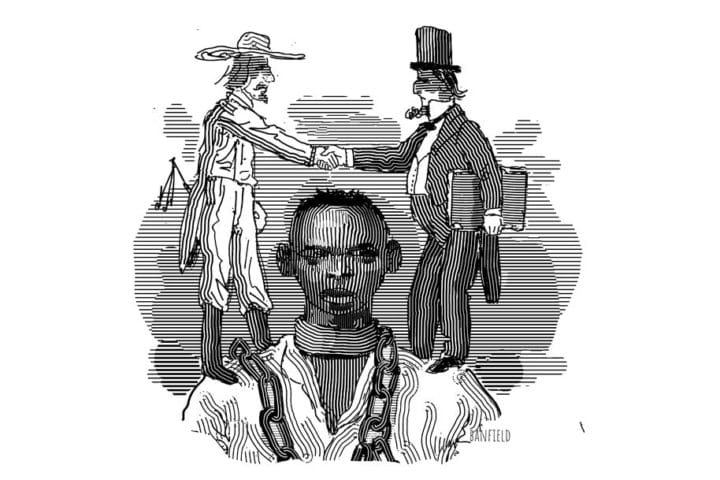

Schaub observes that dates are important in the lives of nations “as markers of the events that shape collective experience.” She thinks that Lincoln understood America partly through its chronological milestones, with three punctuation points standing out: “1787, the date of the writing of the Constitution; 1776, the date of the nation’s declaration of independence; and 1619, the date of the beginning of slavery on the North American continent.” The Lyceum Address, with its concern for the perpetuation of our political institutions and its appeal for “reverence for the laws,” is focused on 1787; the Gettysburg Address, with its famous opening, “Four score and seven years ago,” is centered on 1776; and the Second Inaugural, with its reflection on “the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil,” takes us (roughly) back to 1619.

* * *

The year 1619 has taken on a partisan public significance since the New York Times launched its controversial 1619 Project to mark the 400th anniversary of the introduction of slavery to the American colonies. Schaub has this fact very much in mind when she expresses her conviction “that Lincoln’s greatest speeches matter as intensely today as when first delivered.” In their own time, Lincoln’s speeches tried to bring his straying countrymen back into accord with the “timeless principles of self-government” that animated the American Founding. Americans are wandering again, and Schaub believes Lincoln’s greatest speeches can help get us back on track. The Second Inaugural, in particular, is “the original and better 1619 Project.”

“[A]wareness of the significance of 1619 is nothing new,” Schaub writes. What is new in the New York Times’s 1619 Project is its “attack on 1776, 1787, and even 1865.” The Times’s project holds that America is racist in its DNA—racist in its Declaration of Independence, in its Constitution, even in its abolition of slavery: racism runs in American blood from 1619 through 1776 and 1787 to the last syllable of recorded time. Lincoln argued to the contrary: 1776 was the antithesis of 1619, as were 1787 and 1865; and the anti-slavery moral principle at work on those dates was in keeping with divine judgment proclaimed “three thousand years ago.” In fact, it was, in Lincoln’s words, “an abstract truth applicable to all men and all times.”

As Schaub explains, it was 1861 that enshrined the spirit of 1619, with the establishment of the Constitution of the Confederate States of America. That Constitution specifies that “[n]o…law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed,” and that in any “new territory” which the confederacy might acquire “the Institution of negro slavery, as it now exists in the Confederate States…shall be recognized and protected by Congress and by the Territorial government.”

* * *

“In considering the relation of 1619 to 1776/1787,” Schaub writes, “all Americans should remember what [Vice President of the Confederacy, Alexander] Stephens proclaimed.” She quotes his “Cornerstone Speech” at length:

The prevailing ideas entertained by [Thomas Jefferson] and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with, but the general opinion of the men of that day was that, somehow or other in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away…. Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races…. Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

“[U]nderstanding our history aright,” according to Schaub, “requires taking proper account of these…dates and their true relationship.” We need to learn again from Lincoln how to read our national story: “as a struggle between the principles of natural right, enshrined in the Declaration and the Constitution, and the violation of those principles in American Slavery, beginning in 1619 and spiraling down to its nadir in 1861.” In his Second Inaugural, “Lincoln makes God himself the vindicator and upholder of those principles of right.”

Schaub’s title suggests that the three Lincoln speeches discussed in the book are “His Greatest Speeches.” On the back cover, the book is said to be about “Abraham Lincoln’s three most powerful speeches,” which offer “a complete vision of Lincoln’s worldview.” Schaub does not explicitly make this case in her text. But she does regard the Lyceum Address as “the most profound analysis of the dangers of mob rule,” and she thinks Lincoln himself knew his Second Inaugural was his greatest speech, greater even than the Gettysburg Address. Taken together, she thinks these three speeches reflect the “historico-conceptual constellation of Constitution, Declaration, and American Slavery,” with which no one engaged more deeply than Abraham Lincoln.

* * *

Schaub is writing about speeches, but she reminds her readers immediately that speeches are only part of the statesman’s arsenal. In politics, there is a necessary sequence of logos and praxis, word and deed, and Lincoln was a master of this sequence. “At each step of his political career, the actions of Lincoln were preceded and supported by extraordinary speech—speech that by the compelling quality of its grammar, logic, and rhetoric moved the nation.” But even extraordinary speech cannot always move a nation as it needs to be moved. Schaub doesn’t dwell on the fact, but she notes that each of these great speeches fails to move the nation as needed. The Lyceum Address so failed to persuade the nation to revere its laws that secession and civil war came just 23 years after Lincoln delivered it. Of the Gettysburg Address, Schaub writes: “Mere words could not bring forth the ‘new birth of freedom’” that Lincoln famously spoke of there. “[O]nly battlefield victories could do that.” And regarding the Second Inaugural Address, she acknowledges that “one speech is not going to put race relations on a new footing.”

If those great speeches left much work to be done in their time, what can they do for us now? An early scene of Plato’s Republic reminds us that the wisdom of Socrates himself could not persuade someone who refused to listen. Schaub holds out hope, or at least the possibility, that we might listen now better than we did in Lincoln’s time. In today’s divided America, when questions of American purpose and identity are increasingly contested, Lincoln’s wisdom is still speaking. He took pains to put it accurately into print, so that his reason, rooted in the timeless principles of natural right, might speak to us to the last generation—if only we will listen.

Schaub is very good at persuading her readers to want, literally, to listen. She encourages us, before reading her commentary, to read the speeches—and not just to read them, but to read them aloud or listen to a recording. Introducing the Lyceum Address, she addresses her reader directly: “To prepare, please read through the Lyceum Address, preferably out loud. Alternatively, you might listen to an audio version, available on YouTube,” and she offers a citation. For the much shorter Gettysburg Address, if we haven’t already committed it to memory, she recommends that we “read through it half a dozen times” before turning to her commentary. Here, her purpose is partly to overcome our mind-dulling familiarity with that most famous American speech. To prove her seriousness in making these requests, and to help us follow her advice immediately, she includes the texts of the three speeches in an appendix, with numbered paragraphs that sharpen our attention and connect the texts with her commentary.

* * *

If we follow her advice, and if the muse of the study smiles upon us, I think something like this is likely to happen: first, re-reading and listening to the speeches with the thought in mind that they have something important to teach us brings each speech immediately back to life. It causes us to notice things we hadn’t noticed before (if we are already familiar with the speech) and to think about these discoveries not as historical artifacts, but as living thought from which we might learn. Then, when we turn to Schaub’s commentary, our eyes are opened further. We discover in each of the three cases that there are thoughts and purposes at work in the speech of which we hadn’t been aware, meanings and connotations of words and phrases that surprise us.

We quickly find that to read these three speeches as they deserve and ultimately need to be read, we must read other American speeches and documents from which these are drawn or to which they are related. To hear the Lyceum Address in its fullness, for example, we need to read above all George Washington’s Farewell Address, but also Daniel Webster’s 1825 Bunker Hill speech, Andrew Jackson’s Farewell Address, and even Martin Van Buren’s Inaugural Address.

To begin to think about any one of the speeches, we have to consult again the Declaration and the Constitution, but also virtually all of Lincoln’s major speeches, in which we find his reasoning or rhetoric developed in directions or dimensions neglected or only touched on in these speeches. We find countless incidents in the wildly complicated politics of Lincoln’s time that must be considered fully to understand the thrust of his rhetoric and arguments. Rising from the particular to the universal, with the help of Schaub’s commentary, our minds are further awakened to the great questions underlying these speeches. Just to understand an introductory sentence of the Lyceum Address requires us to reflect on the relation of nature to convention, of time to eternity, of reason to revelation. To plumb the depths of these questions, we must turn to the whole canon of wisdom literature—to the classics of the Western tradition and, again and again, to the Bible. Unschooled as he was, “Lincoln had more command of Scripture than any elected American leader before or since.” His wisdom is “Bible-infused,” as Schaub writes elsewhere, and his speech is rich with the rhythms and harmonies of the King James Version. Her commentary is filled with Biblical references. The Second Inaugural, for example, which is only 701 words long, contains “four direct quotes from the Bible (Genesis 3:19; Matthew 7:1; Matthew 18:7; and Psalms 19:9).”

* * *

From the cosmic and divine, Schaub returns our attention to the microscopic. Just when we think we’ve got the Lyceum Address in our grasp—we’ve read it twice, once aloud, outlined it, and committed some of the best lines to memory—a footnote reminds us that in that speech Lincoln asks 13 questions, distributed in a specific way in different paragraphs, and that he twice answers his questions: “Never!” both times linked to mentions of Napoleon. So we pick it up again prepared to read more carefully. Then we notice, with Schaub’s help, that of the 24 paragraphs in the speech, eight of them are one sentence long, but the longest one, of 20 sentences, is more than twice as long as Lincoln’s entire Gettysburg Address. Schaub offers interesting speculations about why Lincoln should choose so greatly to vary his paragraph length.

Diana Schaub’s commentary on these three speeches is deeply instructive about great issues and events of American history from the founding through the Civil War. But her consideration of this history is as instructive as it is because her primary concern is with political truth, and ultimately with the truth itself about the most important questions. Her commentary becomes an exemplary introduction to civic and liberal education.

Here is a small sampling of the judgments, insights, observations, and “data points” found in her book:

- Schaub regards the Lyceum Address, with its profound analysis of the dangers of mob rule, as urgently relevant to our troubled times. She introduces her commentary on the speech with a brief reflection on the not-so-peaceful assemblies that have been burning down American cities since the summer of 2020. Lincoln “showed how the growing lawlessness—and worse, the tolerance for lawlessness—eroded the people’s trust in their government.” But public trust in government is popular government’s indispensable support. Looking into the future, he showed how “from small beginnings in disrespect for the law, the entire experiment in self-government might be overturned.” Stay tuned.

- There is no place for “civil” disobedience in Schaub’s thinking, and she thinks there is none in Lincoln’s. Short of revolution, the remedy for bad laws is for the majority to use its lawful power to change them and make them better. Our options are ballots or bullets. Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr., are often considered America’s “greatest moral lights.” But Schaub thinks “they fundamentally disagree on this foundational question of the nature of citizenship and the relationship between law and justice.” She recommends reading Lincoln’s Lyceum Address and King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” side-by-side “to test the logic of the two positions.” Schaub has great respect for King’s contributions to America, but fears that his example of “civil” disobedience has eroded the rule of law in ways not unlike John C. Calhoun’s nullification doctrine.

- Lincoln was “a textual fundamentalist, and he was so from the beginning.” Rather than relying on stories of the founding to perpetuate our political institutions, Lincoln invites immediate attachment to the texts of the founding—the Declaration and the Constitution—and the ideas therein. “A nation founded upon a text,” Schaub writes, “has an ever-renewable resource for perpetuity not available to other nations.”

- Before he became president, Lincoln frequently invoked the name of George Washington in his speeches, usually in the peroration. The last time he did this was in his touching farewell to friends and neighbors from the back of a train in Springfield, Illinois, in February 1861. He was about to depart to take up his duties as the newly elected president, and he said, “I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington.” With that greater task upon him, Lincoln ceased to invoke Washington’s name. His presidential speeches increasingly appealed instead to the assistance and guidance of a higher power: to “that Divine Being who ever attended” Washington and “has never yet forsaken this favored land.”

- A small bonus (there are many others): Schaub contrasts Lincoln’s amazingly restrained language rallying Union troops at Gettysburg with an eloquently obscene passage from General George S. Patton’s speech to the Third Army the day before D-Day.

- Another small bonus (for the nerds): In the Lyceum Address, rather than appealing to the altruism of his audience, Lincoln appeals to their self-interest in being law-abiding. Schaub notices possible similarities to the rhetorical strategy of Diodotus in his debate with the demagogue Cleon in Thucydides’s history of the Peloponnesian War.

- Beginning with Lincoln’s eulogy for Henry Clay in 1852, appeals to the Declaration of Independence are found in nearly every one of his major speeches up to and including the Gettysburg Address. But after the Gettysburg Address, “Lincoln makes no further statements about the Declaration. His exposition of the document had achieved its final form.”

- Violating customary rules of grammar, Lincoln begins not just a sentence, but a paragraph (the third in the Gettysburg Address) with a “but”: “But, in a larger sense….” Schaub explains why this is “the most significant use of the word in the literature of English-speaking peoples.”

- In the Gettysburg Address, as in Lincoln’s presidential addresses generally, “Lincoln recedes from view. The first-person singular pronoun ‘I’ is nowhere encountered.” Schaub’s take: “His speech displays the transcendence of self that he hopes to bring forth in others.”

- The data points:

[T]he enslavement of Africans was a global phenomenon. The Arab-Muslim slave trade to the East was in existence ten centuries before the Atlantic trade began and was more extensive in every respect…. On the western side, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database estimates there were 12.5 million Africans transported to the New World, with 10.7 million surviving the Middle Passage. Of those 10.7 million,…388,000 (3.6 percent) landed in North America…. The total number of enslaved persons [in the colonies/United States] from 1619 to 1865 is estimated at five million. Astonishingly, that means that roughly 80 percent of the enslaved persons who ever resided in North America were alive in 1865. But that also means that 80 percent of those ever enslaved in North America were freed in consequence of the Civil War. One soldier died for every seven persons enslaved from 1619 to 1865; and one soldier died for every six persons freed by the 13th Amendment.

Plato ends his Republic (Socrates speaking): “And thus, Glaucon, a tale was saved and not lost, and it could save us, if we were persuaded by it…. But if we are persuaded by me…we shall always keep to the upper road and practice justice with prudence in every way…. And so here and in the thousand-year journey…we shall fare well.” Schaub closes her book: “Though not equal to the omnipresence of the divine, about which Lincoln spoke so beautifully in his Springfield Farewell, Lincoln’s speeches ‘can go with me, and remain with you and be everywhere for good.’ His spirit abides. If we listen and reflect, all may yet be well.”