Books Reviewed

Virgil’s Aeneid is the most influential poem in Western literature. From its first publication in the reign of Caesar Augustus, Publius Vergilius Maro’s epic has played a central role in poetry, education, governance, the arts, and even magic. No longer widely read, its influence still pervades our culture in ways few notice. Most Americans, for example, carry a Latin quotation from the Aeneid with them whenever they leave home. If you doubt this claim, look at the back of a dollar bill. Two Virgilian mottos adorn the Great Seal of the United States, including one 13-letter phrase from the Aeneid, “Annuit Coeptis,” which translates as “[Providence] favors our undertakings.” (The other is “Novus Ordo Seclorum”—a new order of the ages—from Virgil’s Eclogues.) As a symbol of their own divine favor, the American Founders invoked the blessings of the pagan gods who helped Trojan Aeneas build Rome.

Within a generation of Virgil’s death in 19 B.C. the Aeneid had become the central text and textbook of Roman civilization. Educated Romans knew much of the poem by heart, having studied and recited it throughout their school days. Indeed, the epic was so familiar that for centuries Latin-speakers created “original” poems made up entirely of quotations from Virgil rearranged into new meanings—sometimes obscene, sometimes devout. The Aeneid provided a compelling model for later poets and dramatists, including Seneca, Dante, Spenser, Marlowe, and Milton. The poem also inspired painters as dissimilar as Titian, Tiepolo, El Greco, and Turner. Virgil’s works even served as a source book for fortune tellers and magicians. Opening his collected poems to find a line at random was a popular method of predicting the future.

* * *

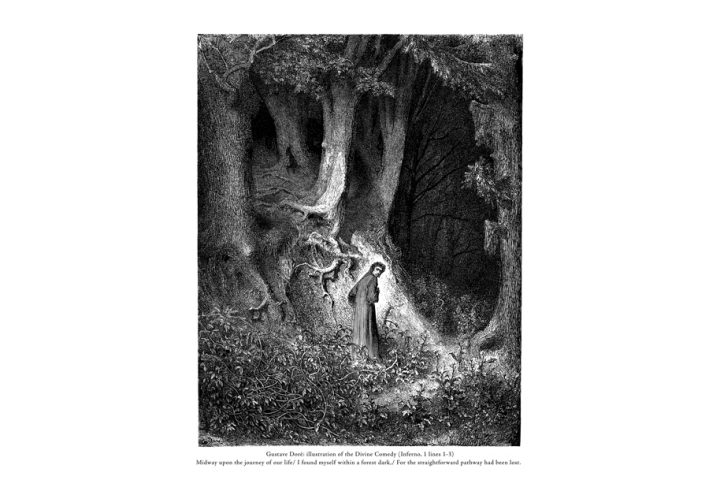

Even Christianity, which had no use for pagan literature, spared Virgil because his fourth Eclogue seemed to predict the birth of Christ. (The poem was probably written to celebrate the potential birth of an heir to Caesar Augustus.) The Church Fathers were also not deaf to the magisterial music and noble vision of Virgil’s story. Saint Augustine covertly patterned his Confessions after the Aeneid to explain the soul’s complicated journey toward God. Dante went even further. He resurrected Virgil himself, “the light and glory of other poets,” as the virtuous pagan to lead him through Hell toward Christian redemption.

The Aeneid is notoriously hard to translate. The plot, characters, and settings come across clearly in English, but the poem feels muted without Virgil’s magnificently moody Latin. His sonorous and sinuous lines can evoke, moment by moment, fear or wonder, exhilaration or erotic rapture. Emperor Augustus’s sister, Octavia, fainted when she heard the poet recite Book VI. Young Augustine wept when he read the epic’s depiction of Queen Dido’s death. There is a reason that Dante praised Virgil as the greatest poet, and medieval legend portrayed the author as a sorcerer.

* * *

For five centuries English-language poets have strived to recreate that spell with mixed results. Oddly, the better the translation the less Virgilian the results. Henry Howard, the earl of Surrey, invented English blank verse in the 1530s to translate sections of the poem. That innovation made Shakespeare and Milton possible, but Surrey’s drab pentameter did little to capture Virgil’s luscious style. In 1697 John Dryden rewrote the poem in shapely heroic couplets. His rhymed version was a commercial and artistic success—a fine Restoration poem quite remote from the Roman original. More recently, Robert Fitzgerald, Robert Fagles, and Sarah Ruden have done estimable translations. They diligently conveyed Virgil’s meaning and manner, but the essential frisson of poetry remained lost in translation. With such a long shelf of dependable translations available, it seemed that what could be done with Virgil in English had been done. Then last year, from beyond the grave, came Seamus Heaney.

The Irish Nobel laureate, who died in 2013, had sometimes mentioned his desire to translate Book VI of the Aeneid, which describes the Trojan hero’s descent into the underworld. Late in life, Heaney had even written a poetic sequence about studying Virgil as a teenager in Belfast. No one suspected, however, that the poet’s daughter Catherine would find a complete translation of the book posthumously among Heaney’s papers. When the existence of this final work was announced, expectations ran high. Heaney’s readers have not been disappointed. Aeneid Book VI is not only a fitting capstone to the career of a poet who venerated the classical tradition; it is a translation at once so original yet faithful that it makes Virgil vividly present in English.

In fairness to Heaney’s predecessors, it is important to note that he translated only one of the twelve books that make up Virgil’s epic. He chose a self-contained and compact section (901 lines in the original Latin) at the heart of the poem, which resonates in the Western tradition as the locus classicus of the Greco-Roman underworld and the prime model for Christian Hell. This episode marks the turning point in Aeneas’s struggle to create a new Troy on the Italian peninsula. Unable to fulfill his divinely-ordained quest, the hero enlists the aid of the Cumaean Sybil, the prophetess of Apollo. Together they descend into Hades, bearing the Golden Bough, which gives them safe passage among the infernal monsters and vengeful deities.

As Aeneas and the Sybil view the terrors of the afterlife, they encounter a succession of legendary figures, such as Charon, Cerberus, Tantalus, and Sisyphus. Conversing with the dead, Aeneas eventually finds the knowledge he needs to create a second Troy. Moreover, he is granted a panoramic vision of his new city’s future greatness. The long, silver-tongued passage culminates in an admonition that Imperial Rome would take as a motto:

“But you, Roman,

Remember: to you will fall the exercise of

power

Over the nations, and these will be your

gifts—

To impose peace and justify your sway,

Spare those you conquer, crush those who

overbear.”

Two thousand years later those lines celebrating Rome’s imperial destiny seem historically accurate but morally deluded. As a Catholic raised in Northern Ireland, a violently divided remnant of the British empire, Heaney understood the cost of imposing peace on those you conquer. In his brief introductory note, he admits to translating this passage with “grim determination.”

What fascinates Heaney are Aeneas’ encounters with his beloved dead. Journeying through Hades, the hero meets the ghosts of his murdered wife; his slaughtered soldiers; his suicidal lover, Dido; and most poignantly his aged father, Anchises. This purifying pilgrimage through death and dispossession fires Heaney’s imagination. Aeneas confronts the harrowing loss of his people and homeland to find a compensatory future for the survivors of his tribe. For Heaney, old and in failing health, the ancient text also becomes a vehicle for retrospection—but less an epic than an elegy.

Virgil died while finishing the Aeneid, and Heaney’s translation is saturated with, but not defeated by, the depredations of time. In his introductory note, he modestly refers to his version as “classics homework,” recalling his teenage years as a student in St. Columb’s College under Father Michael McGlinchey. He also confides that he gravitated toward Virgil after his own father died. He finally embraced the project after writing a poem to greet the birth of his first granddaughter.

Most classical translations are fashioned by intelligence, education, and a modicum of verbal skill. What they usually lack is the animating energy of emotional necessity so tangible in an original work. How can a translator, working at the distance of millennia, conceivably repeat a masterpiece’s secret genesis? It is impossible—unless the writer discovers a parallel necessity in his or her own imagination. When that happens in a work such as Edward FitzGerald’s Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam or Ezra Pound’s Homage to Sextus Propertius, the reader feels the shiver of authenticity. In his Aeneid Book VI, Seamus Heaney may have translated a classic, but he powers the words with energy from personal experience.

When Aeneas meets his father’s ghost in Heaney’s version, the moment feels immediate and contemporary as if the Irish poet were imagining his own father:

“Let me take your hand, my father, O let

me, and do not

Hold back from my embrace.” And as he

spoke he wept.

Three times he tried to reach arms round

that neck.

Three times the form, reached for in vain,

escaped

Like a breeze between his hands, a dream

on wings.

The power of poetry originates primarily in its sound. That is what makes poetic translation so difficult. Virgil’s Latin moves in long, exquisite lines that flow into one another to form great musical movements. No translator has ever successfully emulated that sublime style in English, though John Milton achieved an equally fluent magnificence in Paradise Lost. Heaney triumphs by ignoring the Latinate vowel music of the original. In its place he creates a high style more suited to stress-heavy English, a mix of Beowulf and William Butler Yeats full of consonant clusters and alliteration. Here is Heaney’s version of Virgil’s lines describing the innumerable dead waiting to cross the River Styx:

Continuous as the streaming leaves

nipped off

By first frost in the autumn woods, or

flocks of birds

Blown inland from the stormy ocean,

when the year

Turns cold and drives them to migrate

To countries of the sun.

Ultimately, Heaney’s translation is also an elegy of another sort. It commemorates a lost tradition in education. For centuries, young writers learned Latin as children, and their imaginations grew with classical literature as part of the formative experience. Today classical education is regarded as elitist—the province of professors, preppies, and public school boys. But Heaney’s example shows that there was, until recently, another more democratic tradition of working-class Catholic school kids and their mostly clerical teachers. Ten years after Heaney sweated over his Latin exercises outside Belfast, I sat in a Los Angeles classroom parsing my own 40 lines of “classics homework” from Virgil accompanied by millions of students in Melbourne, Montreal, Buenos Aires, and Munich. Latin was still—just barely—a living language, and wherever Latin went, Virgil presided. That world is now lost, but it bears remembering. There is no more eloquent memento than Seamus Heaney’s Aeneid.