Books Reviewed

Before photography and motion pictures existed, painting and sculpture constituted the visual arts. Done well, they made images come alive. Abigail Adams told her sister of one painting of a wartime scene so vivid and affecting that viewers could hear a dying man’s groans with “grief, despair and terror…strongly marked.” Even mediocre portraiture gave its subjects the only chance to see themselves, besides the reflection the era’s blurred mirrors provided. Hence the demand for art, even along the cultural peripheries of Britain’s 18th-century American colonies.

Colonial America produced a generation of gifted painters despite their limited opportunities to study. No schools in the new world trained artists or provided live models. Great works of art that could inspire and instruct were available only in reproductions. Largely self-taught, aspiring painters crossed the Atlantic to perfect their art in London and Italy, where artists, connoisseurs, and tourists alike went to experience masterworks. American artists often found themselves caught between the higher expressions of metropolitan culture and the familiar home environments their aspirations had transcended. Jane Kamensky’s A Revolution in Color and Paul Staiti’s Of Arms and Artists make it possible to understand Revolutionary America’s artistic milieu. Both well-illustrated volumes explore the relationship between the colonies and Britain, along with the difficulties artists had launching their careers from the empire’s periphery.

Kamensky, a Harvard history professor, shows how John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) was representative of that era’s American painters. Artists were still seen as little more than tradesmen. The English portraitist George Allen described encoding meaning in images by allusion and allegory as the “thinking part of painting,” which elevated its practitioners to the ranks of poets and philosophers. Far less eminent was the limner, an artisan who took likenesses and hawked his wares. Gentility and learning, along with skill, made the difference.

Surprisingly, nothing is known of Copley’s early years other than his birth to Irish immigrants, probably in Boston, and that he may have shown a talent for drawing at a young age. Rather than an inspired genius, he cultivated native talent by hard work and a focus on detail in order to make the leap from humble limner to respected Boston artist. His early works had a stylized aspect until he learned to paint lifelike hands and unforced expressions. A vogue for military portraits gave Copley subjects on whom to practice his skill and, later, contacts that advanced his business—each portrait became an advertisement, drawing new subjects from soldiers in the Seven Years’ War and from the Massachusetts elite.

* * *

By the mid-1760s, Copley gambled on sending works to London for exhibit. At the same time his contemporary, Benjamin West (1738–1820), a tavern keeper’s son from outside Philadelphia, was making the British empire’s center the de facto home to an emerging American School. Wealthy patrons had allowed West to travel to Italy in 1760, where he developed a reputation as the “American Raphael,” and then on to England in 1763. He benefitted from the enthusiasm for empire, brought by victory in the Seven Years’ War. West, embraced by London’s art world, helped found the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768 and later became its second president. Though intending to return to America, he never did.

Copley’s Boy with a Flying Squirrel used his younger half-brother as the model with a specifically American animal for a pet. The meticulous rendering adapted a conventional form in boy’s portraits to carefully play upon surfaces and backdrop while capturing the subject’s features. Praised in London as a sign of what Copley might do with training and great art to observe, it also seemed a little too exact. A wonderful picture by a young man never out of New England seemed faint praise. Later portraits Copley sent for exhibits were not quite in the metropolitan style. He faced growing pressure to leave Boston for London or be dismissed as a provincial artist.

Success in Boston, however, brought Cop-ley prominence, which was cemented by his marriage into the wealthy Clarke family. (His merchant father-in-law’s tea would provoke the Boston Tea Party.) He painted Governor Francis Bernard and General Thomas Gage along with John Hancock, Paul Revere, and Samuel Adams. Gage’s portrait captures the soldier statesman, while Revere’s broke with convention to show a reflective artisan. Each became the standard image of its subject. As tensions grew, Copley tried to avoid political controversy that would distract him from art and risk losing clients on either side. Unlike West, who struggled between his British career and American sympathies, Copley thought independence would come naturally with time and that violent conflict could spiral out of control. Patriots branded him an enemy to his country for signing a friendly address in a letter to loyalist Governor Thomas Hutchinson. Copley left to study art in Italy and then with West in London. His career peaked in 1785 with a portrait of George III’s daughters that few besides the king liked. Like West, he never returned to America.

* * *

Paul Staiti, who teaches American art, architecture, and film at Mount Holyoke College, presents the American Revolution through the eyes of painters as they lived it. Of Arms and Artists shows how their work shaped later generations’ sense of the founding era. George Washington shrewdly commented to the Marquis de Lafayette that painters and writers “hold the keys of the gate by which Patriots, Sages, and Heroes are admitted to immortality.” Art could define a person or event by making history epic rather than prosaic or chaotic.

Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), whom Staiti calls “Philadelphia’s founding artist,” understood art’s political force. Three years younger than Copley and West, and the orphaned son of a felon in Maryland, he turned from saddle-making to portraiture in his twenties. Patrons enabled him to study in London with West and Copley for three years, beginning in 1767, developing a national style distinct from continental European models. The refined skills he brought back led Peale to became the middle colonies’ foremost portrait painter. He arrived in Philadelphia in 1776, amidst war preparations. Besides painting leading figures of the Continental Congress, he served in the Pennsylvania militia and fought at Princeton in 1777.

* * *

Once the British evacuated Philadelphia in 1778, he received a large commission to paint what Staiti calls the United States’s first great history painting: a portrait of General Washington for the Pennsylvania State House. Peale cast Washington as republican hero, adapting the pose from a 1763 court portrait of King George III. Standing “animated but unperturbed” beside a cannon and other trophies after victory at Princeton—a pivotal moment in the war—Washington is presented “in possession of human attributes so rare that they made him the ultimate paragon of virtue.” Copies in Europe drummed up support for the revolution.

Peale had told Benjamin Franklin in 1771 that achieving independence would transfer to America from servile Europe the mantle of great art. Besides organizing pageants and painting statesmen, he founded an American museum to showcase what the new republic alone possessed. Because of the public’s preference for novelties and popular entertainments, not the fine art that had defined Peale’s career, he found himself in a postwar world that fell short of his expectations.

Fifteen years younger than Peale, Connecticut’s John Trumbull (1756–1843) fared better. His father, the only royal governor to side with the Revolution, planned a career as a lawyer or clergyman for his son, believing them more stable than an American painter’s life. Trumbull attended Harvard, where he was drawn to the revolutionary cause as well as the work of Copley. After a short stint in the Continental Army, he became one of West’s students in London, where he landed in prison on charges of treason. (West stood bail.) Later, during negotiations with Great Britain over the U.S.-Canadian border, Trumbull served as John Jay’s secretary.

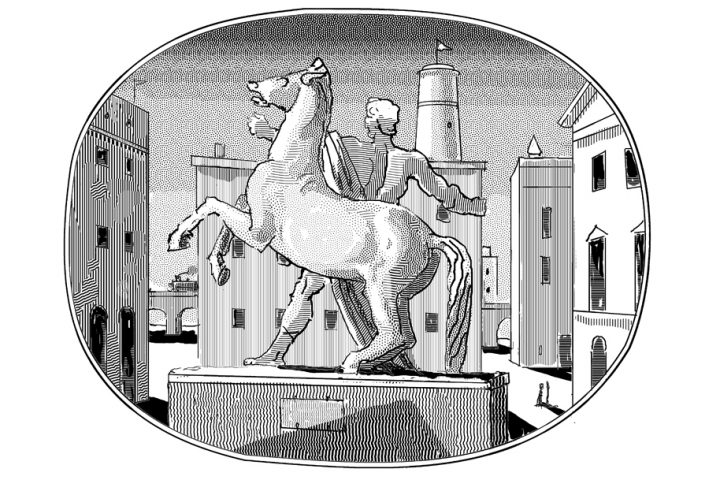

The best educated among American painters, Trumbull drew a politically charged parallel between the American crisis and republican Rome. His second picture at the Royal Academy exhibit in 1784, depicting the Roman Senate giving Cincinnatus command of the army, made a thinly veiled reference to Washington.

West himself had aspired to paint epic scenes of America’s history as he had for Britain, such as The Death of General Wolfe. His painting of the Peace of Paris that recognized American Independence remained unfinished, however. The humiliated British diplomats refused to sit for his work, which framed the scene as an intimate group modeled on a family portrait emphasizing reconciliation.

* * *

The task of bringing America’s epic origins to life fell instead to Trumbull, who in 1785 began planning a series of historical pictures. The first, completed in 1786, depicted physician Joseph Warren’s death at Bunker Hill. By casting Warren as a martyr to the revolutionary cause, Trumbull departed from the strict details to capture a deeper truth about heroism. Painstaking research, taking portraits of people to depict accurately their part in larger scenes, and diplomatic service in Britain delayed later works in the series. Thomas Jefferson, who brought a connoisseur’s sensibility to art along with an eye for self-promotion equal to Benjamin Franklin’s, guided Trumbull’s painting of the Declaration of Independence, which cast the Virginian as the central figure. Between 1819 and 1826, as the revolutionary generation began passing from the scene, Trumbull delivered several more oversized canvasses to be displayed in the new Capitol rotunda, including scenes of Columbus’s discovery of the Americas, the Pilgrims’ arrival at Plymouth Rock, Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown, and General Washington’s resignation of his commission.

John Adams believed events should be recorded with an exactitude at odds with artistic license to make deeper points. He feared Trumbull would reduce the revolution to a cartoon of history, and that his grandiose art might corrupt citizens by duping them into thinking monarchy natural and a tyrant beneficent.

As Staiti observes, Adams “had a keen eye.” Never diffident, he commissioned a portrait in London by Copley, whom he had known in Boston before the Revolution, to commemorate his diplomatic work in Europe as the civilian parallel to Washington’s heroic military portrait. Shown in full length with an almost challenging expression, the figure’s plain but polished dress contrasts with an elegant background including a globe and map of North America. Convinced “that plain living was the outward sign of high thinking,” Adams cast himself as a republican statesman. Copley took great care collaborating with his subject on a work he matched with an earlier portrait of Samuel Adams. The result disenchanted Adams, who thought it excessive and left the portrait with Copley. Having revealed too much of its subject for comfort, the painting now hangs in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

* * *

Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), an entirely apolitical man committed to no cause beyond his own advancement, went to London, too, becoming another American prodigy of West’s. Remarkable talent enabled him to overcome a lack of business sense and an even more acute lack of integrity. Subjects forgave his failings because of his ability to capture them so well. Stuart’s image of President Washington, used on the $1 bill, is more than famous, but his paintings of other statesmen made him the American portraitist of the age. One he began of President Jefferson in 1805 deliberately broke with the elevated image of the presidency his two predecessors had sought to project. Rather than in a stylistic expression of power, Jefferson appears in a scholarly pose working at a desk on the people’s business.

The artists of the Revolutionary Era found posthumous fame in the United States as collectors in the late 19th century sought out their works. The westward spread of learning and art coincided with renewed interest in colonial Americana. West, Copley, Peale, Stuart, and Trumbull came back into their own, defining how subsequent generations viewed pivotal events and the figures behind them. As these two splendid new books show, the leading painters of the American Founding, too, were in key ways creators of a new world.