California’s Progressives achieved breakthrough victories in the 1910 elections. With some running as Democrats, others as Republicans, and still others disdaining party labels altogether, Progressives won governing majorities in the state legislature. Hiram Johnson, the candidate of the “Lincoln-Roosevelt League,” was elected governor, and later became Theodore Roosevelt’s vice-presidential running mate on the Progressive ticket in 1912. (One reason Roosevelt carried California that year was the Progressives were powerful enough to keep the Republican nominee off the ballot; President William Howard Taft was forced to seek California’s electoral votes as a write-in candidate.)

At next year’s parades marking the centenary of the Progressives’ triumph, confetti suppliers and marching bands may have to be paid with IOU’s instead of cash. California’s bonds are rated lower than any other state’s; its budget deficit, relative to the size of the state’s population, is higher than any other’s. The current recession is the proximate cause of California’s crisis, but other states devastated by the economic downturn, such as New York and Florida—even Michigan—face choices about taxes and spending that are far less dire. A growing number of observers argue that California’s real problem is that it has become ungovernable. Kevin Starr, for example, who just published the eighth volume in his comprehensive history of the Golden State, recently told an interviewer, “In our public life, we’re on the verge of being a failed state, and no state has failed in the history of this country.”

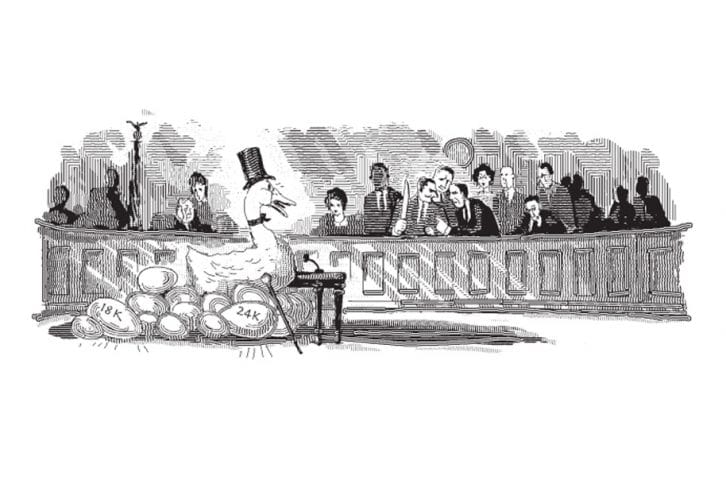

Rome wasn’t sacked in a day, and California didn’t become Argentina overnight. Its acquired incapacity to manage its own affairs has been a long, complicated story, with many contributing factors rather than a single villain or tragic flaw. No analysis of California’s political demise, however, would be complete without discussing how the Progressive legacy has undermined the state’s ability to govern itself.

Hyperdemocracy

According to historian Alonzo Hamby, the framework for Progressive politics was the conviction that the political conflict was between “the people” and “the interests.” It followed that the highest political duty was to help the people resist and ultimately triumph over the interests. One problem with this framework is that it lends itself better to the disdain than to the practice of politics. “The Progressives did not like politics,” writes political scientist Jerome Mileur, because “the politics they saw was not about the public purpose of the nation, but was instead consumed by local interests and private greed, indifferent alike to the idea of a great community and the idealism of grand purpose.”

As a result, Progressivism’s anti-politics was designed for the people as they ought to be, not as they really are. Positing that the fundamental choice is between the people and the interests presupposes that the people are authentic only when they are disinterested. The Progressives’ goal was to equip the people with the means to advance encompassing, lofty ambitions by thwarting the interests’ narrow, selfish ones. The means to this end was to collapse the constitutional space between the people and the government, dismantling the political mechanisms that conferred unfair advantages on connected insiders. As the New Republic editorialized in 1914:

The American democracy will not continue to need the two-party system to intermediate between the popular will and the governmental machinery. By means of executive leadership, expert administrative independence and direct legislation, it will gradually create a new governmental machinery which will…itself be thoroughly and flexibly representative of the underlying purposes and needs of a more social democracy.

The California Progressives’ reforms included the direct primary, the nonpartisan election of judges, the referendum and initiative, and recall elections. The results, a century later, cannot be what anyone who wishes democracy well had in mind. As journalist Peter Schrag argues in California: America’s High-Stakes Experiment (2006), the state’s people are groaning under the weight of all the weapons they have been given to fight the interests. California, he writes, has

seven thousand overlapping and sometimes conflicting jurisdictions: cities, counties, school districts, community college districts, water districts, fire districts, park districts, irrigation districts, mosquito abatement districts, public utility districts, each with its elected directors, supervisors, and other officials, a hyperdemocracy that, even without local and state ballot measures, confounds the most diligent citizen.

Hyperdemocracy needs disinterested citizens, but produces uninterested ones. “California has a dozen major media markets,” writes Schrag, “where few newspapers and even fewer TV stations recognize the rest of the state, much less pay much attention to it.” For all the scrutiny these media devote to state government, the capital city of Sacramento “might as well be on the moon.”

Admittedly, Progressivism has a better record of promoting conscientious, congenial, efficacious governance in states with long, dark winters, such as Wisconsin and Minnesota. It’s a lot easier to get a respectable turnout for a city council or school board meeting in those states than in one with 840 miles of coastline and 1,100 golf courses open year-round. Victor Davis Hanson, a native Californian, suggests, “Perhaps because have-it-all Californians live in such a rich natural landscape and inherited so much from their ancestors, they have convinced themselves that perpetual bounty is now their birthright—not something that can be lost in a generation of complacency.” The recent observation by Ron Kaye, the former editor of the Los Angeles Daily News, about the widespread disengagement from politics in the state’s largest city applies with comparable force to Californians generally: “Mostly, people have never paid much attention. Life is too good, the sun is too sweet.”

Existentialists without Portfolio

Trying to apportion the blame for California’s dysfunctional politics between its good climate and bad constitution is, ultimately, more interesting than important. The reality is that the state’s hyperdemocracy enables Californians to periodically rebuke the governing class in the manner of Network‘s Howard Beale: “We’re mad as hell, and we’re not going to take it anymore!” One of history’s little jokes is that these rebukes have, more often than not, been defeats for the bien-pensant liberals who are the descendants of California’s Progressives. In the last three decades the voters have rejected unlimited property tax increases; public services for illegal immigrants, no questions asked; affirmative action; bilingual education; and same-sex marriage.

What California’s hyperdemocracy does not facilitate, however, is the realization of the people’s quotidian interest in government that is fair and efficient, that respects their rights scrupulously and spends their tax dollars carefully. Californians who already have lives and jobs are not in a position to make citizenship a parallel career. Among the respects in which all men are created equal is that everyone’s week contains exactly 168 hours, regardless of how many public hearings your air quality management district schedules, or how many reports get posted on its website.

Contrary to the New Republic‘s confident assertion 95 years ago, it turns out that American democracy does need political intermediaries between the people and the government. Such intermediaries are capable of bringing the people’s concerns to bear on the thousands of small decisions made every week that determine the success and reliability of the government endeavors affecting them most directly. The Progressive legacy in California renders these intermediaries, especially political parties, too weak to aggregate and represent the concerns of the vast majority of citizens for whom lives of constant civic vigilance are impossible.

The New Republic welcomed the demise of political intermediaries out of the belief that the emerging governmental machinery would do a far better job of representing the people by relying on “executive leadership, expert administrative independence and direct legislation.” Each of these mechanisms, however, is problematic. California has demonstrated that direct legislation is a good way for the people to yank the government’s leash and thwart its excesses—but too blunt an instrument for managing the innumerable details that control the provision of education, public health, law enforcement, and other essential services.

The Progressives were enthusiastic about executive leadership. As Woodrow Wilson said during the 1912 presidential campaign, “The business of every leader of government is to hear what the nation is saying and to know what the nation is enduring. It is not his business to judge for the nation, but to judge through the nation as its spokesman and voice.” The problem, in our federal system, is that the key word in this Napoleonic job description is “nation.” Whatever sense Wilson’s formulation makes, and whatever appeal it holds, applies to the presidency. The idea that governors, mayors, and school board presidents should be the vessels for their constituents’ hopes and dreams is ludicrous. People ask their state and local officials to deliver reliable public services and impose low taxes, not to be existentialists without portfolio.

By process of elimination, then, the burden of the hopes for bringing the will of the people to bear on the workings of government comes to rest on “expert administrative independence.” It’s the worst bet of all. The idea of relying on independent administrators to connect the people to the government is fundamentally contradictory: it’s people that administrators are supposed to be independent from. The people are not a problem, of course, because “the people” —the hypostasized, disinterested abstraction for which Progressivism was designed—selflessly arrive at all the same conclusions as the independent administrative experts. Indeed, when the leaders lead but people don’t follow, when the experts pronounce but people don’t assent, the problem can be reliably ascribed to people’s failure to live up to their responsibilities as “the people.”

In the face of this dereliction, leaders and administrators have the capacity and duty to manifest the “underlying purposes and needs of a more social democracy.” What these underlying purposes and needs lie under are the purposes and needs real people express around dinner tables, on the sidelines during their kids’ soccer practice, and in voting booths. The way to render democracy more social is thus to render it less political. Leaders and administrators can see through people’s imperfect expression of their preferences, and govern on the basis of the Platonic ideal of “the people’s” aspirations, which they apprehend more clearly and reliably than do actual citizens themselves.

Unionocracy

The brigades of government administrators who govern in the name of the people have grown more organized and powerful over the past 50 years as unions of government employees have flourished. The history of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) is instructive. According to the AFSCME website, it was not established out of concern for labor unions’ usual preoccupations—wages, benefits, and working conditions. Rather, in 1932 “a small group of white-collar professional state employees met in Madison, Wisconsin,” another Progressive stronghold, “to promote, defend and enhance the civil service system.” They were concerned about their job security, but in a way that had as much to do with professional dignity and political beliefs as it did with bread-and-butter finances. According to AFSCME, the Wisconsin civil servants “feared that politicians would implement a political patronage or ‘spoils’ system and thousands of workers would lose their jobs.”

The spoils system would not have precluded Wisconsin’s white-collar professionals from keeping or regaining their government jobs—but would have decoupled their tenure from their expertise and independence. They would have been forced to demonstrate their ongoing utility to politicians who were, in turn, forced to justify their own utility to the voters. Rather than suffer this affront, AFSCME’s founders organized politically, and “saved the civil service system in Wisconsin,” inspiring other public employees around the country to do the same. By 1936 these discrete groups were a national trade union, chartered by the American Federation of Labor.

Today, AFSCME claims 1.6 million members, making it one of the country’s largest unions, and one of the few that has grown while those based in smokestack industries like automobiles and steel have shrunk. It does not have the field to itself, however. In California, for example, where 179,000 AFSCME members work for state and local governments, slightly more than half of the 193,000 unionized state government employees belong to the Service Employees International Union, which walked out of the AFL-CIO in 2005. The rest of the state’s represented employees are divided, for collective bargaining purposes, among a long list of narrowly specialized unions, such as the California Association of Psychiatric Technicians, and the California Correctional Peace Officers Association.

For two decades after it was chartered in 1936, AFSCME’s priority remained enacting and strengthening civil service laws. By 1955, though, AFSCME’s membership had come to include blue-collar as well as white-collar workers, and its priorities shifted to establishing its right to bargain collectively with states and municipalities over wages and terms of employment. A number of strikes by public employees were needed to win this contested claim. A turning point came in 1958 when the mayor of New York, Robert F. Wagner, Jr., granted collective bargaining rights to unions representing city workers. (Wagner’s father, as a U.S. senator from New York, had authored the fundamental law legitimizing labor unions, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, usually known as the Wagner Act.)

Other states codified the right of public employees to bargain collectively in the following years. California did so in a series of laws passed between 1968 and 1979. It’s important to note that strikes by public employee unions played a much bigger role in establishing collective bargaining rights than in the exercise of those rights after the unions had been recognized. United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA), for example, went on strike for five weeks in 1970, only to have the agreement that ended the strike nullified by the courts due to the absence of a statewide collective bargaining law covering public school employees. The state legislature enacted such a law in 1975, and the only subsequent strike mentioned in UTLA’s official history is one in 1989 that lasted 9 days and resulted in a three-year contract with the Los Angeles Unified School District.

Strikes have become rarities in the private sector because strike threats are not believable in industries that are downsizing and face low-cost competition from around the world, and the people on both sides of the bargaining table know it. Strikes have become rarities in the public sector, too, but at a time when those unions have been gaining members and strength. Whereas private-sector unions don’t strike because it would be injurious, public-sector unions don’t strike because it would be superfluous. Having bargaining leverage against the management negotiators across the table is all well and good, but it’s radically inferior to negotiating when labor dominates both sides of the table. As the Los Angeles teachers union summarizes its prevailing strategy, “UTLA has successfully backed candidates for the school board who have vowed to place top priority on students and the classroom.” In low-turnout, below-the-radar school board elections, the union’s involvement is rarely less than decisive. Earlier this year it spent more than $287,000 on behalf of a candidate who easily won an election for one of the seven seats on the L.A. school board.

The state’s major public employee unions have all followed this approach, and it has been a tremendous success. Dan Walters of the Sacramento Bee says California’s “public employee unions wield immense—even hegemonic—influence” over the Democratic majorities in the state legislature. Even more than in most states, gerrymandering in California means that, in the overwhelming majority of districts, competition between politicians who belong to the same party is common and intense, while truly contested general elections between those who belong to different parties are exceedingly rare. Primary elections are the only ones that aren’t exhibition games, and nothing matters more in a Democratic primary than getting endorsed by public employee unions. Those endorsements guarantee two crucial political resources—money and manpower. No other political entity comes close to the unions’ ability to produce effective, sophisticated get-out-the-vote campaigns with hundreds of experienced workers. According to the Los Angeles Times, the California Teachers Association, the state affiliate of the National Education Association, “has deep pockets, a militia of more than 300,000 members to call on and a track record of making or breaking political careers.”

Paying the Piper

California’s public employee unions not only sit on both sides of the bargaining table, but also have it both ways rhetorically. They are happy to act as ventriloquists when the people don’t know what to say or think about an endless list of complicated, arcane, and tedious policy questions. It turns out that the people are deeply, deeply concerned that the state’s public employees have excellent wages, benefits, pensions, and job security. California Democrats, like Democrats everywhere, never pass up an opportunity to express their solicitude for children. When, however, that solicitude recently led to the consideration of ways to enroll more children in state healthcare programs, the Democrats’ most powerful constituency prevailed against their most vulnerable one. According to Chris Reed, an editorial writer for theSan Diego Union-Tribune, the unions scuttled an initiative that would have let parents enroll their children in the health programs online “because it might have led to layoffs of clerks at county social-services offices.”

It’s neither a coincidence nor a surprise, then, that California’s government employees receive higher compensation than those in any other state. The Census Bureau’s latest figures cover the year 2006, and show that California’s local government employees were paid at an average annual rate of $60,780, 33% above the national average. State employees had average annual compensation of $65,964, 34.2% above the national average. Many states and regions have lower costs of living than California, reducing the national compensation averages. But California’s public workers receive more, often significantly more, than government employees in other states with high living costs. Californians who work for local governments were paid 7.7%, 9.1%, 11.5%, and 21.4% more than their counterparts in New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts respectively. California’s state employees received 8.6% more than Connecticut’s, 13.1% more than New York’s, 19.9% more than those in Massachusetts, and 28% more than Maryland’s.

Nationally, 5.4% of the population works for a state or local government, but only 5% of the California population does so. Only nine states have a smaller proportion of their population employed in the public sector. The services rendered by state and local governments are very labor-intensive, so that even if California saves some money by employing fewer workers than other states, it pays out a larger amount by compensating them at higher rates. One analysis, for example, shows that it costs California $45,000 to keep one inmate in prison for one year, compared to an average cost of $27,237 for the nation’s ten most populous states. As a consequence, Dan Walters argued in the Sacramento Bee, the state would save $4 billion a year by reducing its incarceration costs to the average in the other big states.

Walters’s colleague Jon Ortiz recently reported that in 2008 “California state correctional officers made an average $63,230, more than any other federal, state or local counterpart in the country.” Even before factoring in overtime, which increased the pay of the average California prison guard a further 14.9%, the compensation level in California was 53% above the national average. These compensation levels are not happenstance. Ortiz says the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA) has “built a reputation for its textbook application of raw political force, fueled with enough money to sway elections and build or destroy political careers.” A CCPOA spokesman told Ortiz that the union’s 2002 contract, providing a 37% pay increase over five years, better retirement benefits, and fewer restrictions on sick leave, was the best labor contract “in the history of California.” What goals the union can’t achieve through collective bargaining and politics it pursues through litigation. It’s currently suing to secure “‘donning and doffing’ pay,” according to Ortiz, “which compensates officers for the time required to put on and take off a uniform, vest and other equipment at the beginning and end of a shift.”

Corrections outlays account for 10% of California’s state general fund. Apply the same political dynamic to the rest of the state’s expenditures, as well as those made by all the cities, counties, and “special purpose districts,” and you end up with a public sector that is one of the country’s most expensive. The Census Bureau provides detailed information on state and local government finances in each state for a 14-year period, from the 1991-92 fiscal year to 2005-06. By combining that data with the Census Bureau’s annual population estimates, and the Commerce Department’s implicit price deflator for state and local governments, we can compare government expenditures across the 14 years and 50 states. In 1991-92, California’s combined outlays by all state and local governments were, on a per-capita basis, the eighth highest in the nation, after six states and the District of Columbia. By 2005-06 they were the fifth highest, behind only Washington, D.C., Alaska, New York, and Wyoming.

Adjusted for inflation, California’s per-capita outlays increased by 21.7% between 1992 and 2006; the increase for the other 49 states and the District of Columbia was 18.2%. What’s striking is that California is an exception to the pattern we were told to expect in Statistics 101, the regression to the mean. The states where inflation-adjusted, per-capita government outlays grew the fastest between 1992 and 2006 were, generally speaking, ones where those outlays were among the lowest to begin with. Conversely, of the ten states that had the highest per-capita public expenditures in 1991-92, California and Wyoming are the only two that saw those expenditures, adjusted for inflation, grow faster than the national average over the next 14 years.

A few counterfactuals show that these different growth rates matter—a lot. If constant-dollar, per-capita expenditures by California’s state and local governments had grown by 18.2% between 1992 and 2006, the rate for the rest of the country, rather than 21.7%, California’s public sector would have spent $10.6 billion less than it actually did in 2006. While California government expenditures grew faster than the national average, even states not famous for the parsimony or integrity of their public sectors, such as New York (16.4%) and New Jersey (12.8%), grew more slowly. If California’s outlays had grown only fast enough to keep pace with population growth and inflation from 1992 to 2006, public spending would have been 17.8% less in 2006, $300 billion rather than $365 billion. The resulting level of per-capita government outlays in 2006 would have equaled neither Somalia’s nor Mississippi’s, but…Oregon’s, which is rarely considered a hellish paradigm of Social Darwinism.

Expensive and Ineffective

Clearly, paying your employees more than any other state is an excellent way to bend the governmental cost curve upward. The danger, however, is that stray efficiencies might pollute the system and undermine these efforts. Higher payments to retired government workers eliminate this risk. In 1999, just as the dot-com boom was ending, California’s state government concluded the good times would go on forever, and passed a law that made the pension formulas for state employees dramatically more generous, and encouraged municipalities to adopt the same approach. State employees could retire at age 55 with a pension exceeding half of the highest salary they ever received. Public safety workers could retire at age 50 with 90% of their salary. Lifetime cost-of-living adjustments protected the pensions, which were paired with generous health insurance benefits.

Two problems. First, the assurances by officials from the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) that a permanent stock market boom would cover the enhanced pension obligations proved immediately, and ruinously, off base. The state’s required contribution to the more generous retirement system in 2008-09 was supposed to be $379 million, according to the original CalPERS projection. The actual figure needed to cover the amount not generated by the CalPERS investment portfolio was $4.6 billion.

Second, the same political forces that made the public pension system extravagant keep operating to make it ever more unaffordable. One result is that the portion of the state workforce eligible for the more generous pension benefits available to public safety workers has increased steadily. A law passed in 2002, for example, guaranteed that the chance to retire at age 50 with 90% of salary would be available not just to firefighters and police officers, but also to the dedicated public safety officials who put their lives on the line every day to protect their fellow citizens from wobbly billboards and tainted milk.

Asked to assess his team before the beginning of the season, a basketball coach once said, “We’re short, but we’re slow.” Californians can draw similar encouragement from the accumulating evidence that while their government is increasingly expensive, it is also increasingly ineffective. The public interest, as interpreted by the government workers’ unions, demands no public employee be fired before incontrovertible justification for his termination had been established through an elaborate, prolonged series of fact-finding procedures and hearings. As a result, Californians will apparently have to regard with equanimity the prospect that some, or even many, public employees whose professional conduct ranges from borderline incompetent to borderline illegal will enjoy lifetime job security while crossing off the pay periods before that first pension check arrives.

A recent Los Angeles Times series, “Failure Gets a Pass,” demonstrated that it is “remarkably difficult to fire a tenured public school teacher in California.” Knowing the gauntlet of proceedings and investigations they’ll have to run, administrators overwhelmingly opt to live with problem employees, saving their attempts at termination for “the most egregious cases,” those involving “blatant misconduct, including sexual abuse, other immoral or illegal behavior, insubordination or repeated violation of rules such as showing up on time.” Being a mediocre or even a terrible teacher is rarely a sufficient reason to get the termination process started. Even so, special review panels decide in favor of the teachers in more than one third of all cases.

It’s impossible, with so many ways for the process to end or be prolonged, to compute the average duration of a dismissal procedure. One middle school principal estimated the typical time period needed to fire a tenured employee at five years—seven months longer than it took to build the Golden Gate Bridge.

The teachers unions found nothing in the Times series to apologize for. “The union is bound by law to defend our members, and we do,” A.J. Duffy, the president of United Teachers Los Angeles, told the paper. He allowed that the school district’s job is to weed out “failing teachers,” but quickly made clear that the union would use its political power to prevent the school districts from acquiring the means necessary to discharge that responsibility. In the wake of the newspaper revelations the Los Angeles school board passed, on a 4-3 vote against union opposition, a resolution asking the state legislature to look into changing state laws to make it easier for school districts to fire teachers accused of serious crimes. UTLA immediately made clear that this defeat was a momentary, meaningless setback, insisting confidently that the state legislature would respond to the resolution only in ways the teachers unions endorsed.

The school district also created a task force to explore the question of assessing teachers’ effectiveness. UTLA’s abiding commitment to the schoolchildren of Los Angeles led its president to declare, “If I’m comfortable with the composition of the task force, then I’ll agree to be a part of it. Otherwise, that issue is going nowhere.”

Reality Check

That imperious threat will almost certainly prove to be an accurate prediction. The fundamental dynamic of modern California politics is that the permanent government, operated by or at the behest of the public employee unions, can routinely produce outrageous results through outrageous processes—as long as it stops just short of the tripwires that cause the voters to become genuinely outraged. If the permanent government stays inside that perimeter, it can run California pretty much the way it wants to. When it crosses the line, and provokes the state’s distracted hyperdemocracy to become focused and angry, the permanent government runs the risk that the voters will reassert their prerogatives and reduce the government’s latitude for action.

Earlier this year, for example, the state government’s tentative solution to its budget crisis required the voters to enact a typically complex, indecipherable cluster of ballot propositions on taxes and spending. Because the propositions’ tax increases were immediate and certain, while their spending restraints were long-term and nebulous, voters were skeptical from the outset. They shifted into outrage mode when reports surfaced a month before the election that leaders of the state legislature, who insisted night and day that the state was broke, had found $551,000 to give pay raises to legislative staffers. The raises were quickly rescinded, but the political damage was done. None of the ballot measures that mattered secured even 40% of the vote.

It took a while for some parts of the permanent government to realize it had suffered a setback. After the defeat of the ballot propositions the public employee unions took the position that when the voters reject tax increases, the correct response is to press for bigger ones. AFSCME proposed a budget alternative that relied on new taxes designed to augment state revenue by $44 billion per year, but which did not cut one dollar from a single spending program. It presented its list of tax increases to the Democrats in the legislature with precise instructions: “If you opposed any of the options above, please indicate your reasoning, and your SPECIFIC proposal(s) for achieving similar revenue or savings.”

Not even one Democratic politician turned in that homework assignment. Union leaders told the Los Angeles Times that they were “appalled” that Democratic leaders were considering serious budget cuts “without first making a stand for bigger, broader tax hikes.” The president of the California Federation of Teachers said, “For some reason, they are unwilling to stand up and say ‘This is not what I was elected for.'” Nonetheless, according to the story, “even some of the most liberal Democrats” in the legislature said the idea of closing the state’s deficit largely or entirely through tax increases ignored the fiscal and political realities, among which was “the reality of an angry public.”

Strategies, Left and Right

In California, the political strategies of both conservatives and liberals concentrate on how to deal with that angry public. The conservative strategy is to get the public angry, and see that it stays angry. Conservative talk-radio hosts compete to identify the latest and most astounding outrage, and to see who can denounce it most stridently. The liberal strategy is, as noted, to avoid rousing that public to anger, but also, when the voters do put on their war paint, to wait for their ire to ebb due to the passage of time and the inevitable reappearance of life’s many nonpolitical preoccupations. When the anger has passed, government-as-usual can resume without meddling by citizen-amateurs.

Three of California’s last four governors, and six of its last nine, have been Republicans. The politicians who secured those victories immediately found it necessary to cooperate with a dominant opposition party; California is, in every other respect, a state that has been becoming more Democratic for as long as its oldest residents have been eligible to vote. California has not given its electoral votes to a Republican presidential candidate since 1988, or been represented in the U.S. Senate by a Republican since 1992. Of the 53 Californians in the U.S. House of Representatives, 34 are Democrats. In the past half-century, each of the two chambers of the state legislature has seen a Republican majority—once. The GOP’s state senate majority endured for two years, the one in the lower house for less than a single year.

The evidence is incontestable: the liberal strategy of waiting for the public’s anger to subside is far sounder than the conservative strategy of hoping it will gather strength. The liberal calculation rests on a shrewd assessment, not only of human psychology but also of modern mobility. California is not yet East Germany, which means that one of the ways Californians who are mad as hell can decide not to take it any more is by moving away. The Census Bureau shows that California, the state that used to be a magnet, has experienced negative “net domestic migration” since 1990. Between 1990 and 2007 some 3.4 million more Americans moved from California to one of the other 49 states than moved toCalifornia from another state.

States don’t conduct exit interviews, so there’s no way to tell how many ex-Californians left paradise because the taxes were too high, the public services too shoddy, and the unions too overbearing. Whatever the tally, one problem for conservatism in California is that the conservative critique of the state’s governance argues as strongly for flight as it does for fight. It is possible to advocate a national policy agenda by invoking patriotism, but “state-riotism” is a far weaker sentiment. Indeed, one could argue that the best way not to let California’s crisis go to waste is to let it run its course. As public employee unions assert ever more power over the affairs of a state that has steadily worsening economic and political prospects, opponents of unlimited government across the country and around the world can boil their arguments against taxes, regulation, and bureaucracy down to one rhetorical question: “Do we really want to run things here the way they do in California?”

If we could count on vice to be its own punishment, however, the world would have much less of it. When Rudy Giuliani became mayor of “ungovernable” New York City in 1994, he demonstrated that a successful commitment to limited but effective government is far more resonant than affirming that unlimited and ineffective government invariably fails. Some people once hoped Arnold Schwarzenegger would become California’s Giuliani. Regrettably, Schwarzenegger’s improbable ascent to the governor’s mansion in 2003, on the same day the incumbent Democratic governor lost a recall election, proved to be the only spectacular ending Schwarzenegger could deliver without a script and special effects. Other silver bullets, such as the nation’s strictest term limits for state legislators, have proven equally disappointing.

Reclaiming California

If California is to have a more conservative future, it’s going to result from patient, painstaking attention to political and policy details, not from finally discovering the dramatic transformation that catalyzes a blue state into a red one. Conservatives have gotten most of the mileage they ever will out of efforts to translate Californians’ anger into a polling place backlash against the permanent government. For conservatism to revive its fortunes, and California’s, far-sighted resolve will have to do the work that populist outrage cannot. Two connections must be forged for that project to succeed. First, the state’s Republican Party will have to break free from the gravitational pull of the Progressive legacy to establish itself as the vital political intermediary between the public’s desire for fair and frugal public services, and a newly chastened government that delivers them conscientiously. The historical record clearly establishes that direct legislation and galvanizing leaders are not adequate to this task, and independent administrative experts can be trusted only to sabotage it.

Second, the institutional capacity of the Republican Party will be inadequate to its mission unless it persuades Californians that they have an urgent, abiding, and legitimate interest in reclaiming their government from the public employee unions who have asserted squatters’ rights over it. The logic of Progressivism called for independent administrators to discern and implement the people’s disinterested, inchoate aspirations for government. Instead, the permanent government has become increasingly adept and brazen at advancing its own private interest by invoking platitudes about the public’s. The vindication of the public’s real, as opposed to its faux, interest will require walking back, over several years, the depredations the permanent government has perfected over decades. The public employee unions do not need elaborate PowerPoint presentations to convince their members they’ll secure tangible rewards by electing pliable Democrats. Private citizens, however, will have to be shown that the permanent government has forfeited the right to be entrusted with pursuing the people’s prosaic but compelling interest in securing effective public services by paying fair, sustainable taxes. The voters will have to be persuaded that these legitimate demands can only be addressed by electing principled conservatives to public offices both prominent and obscure.

A telling, because surprising, place to begin that argument is by contending that the permanent government has disqualified itself from superintending California’s welfare state, ostensibly its reason for existence. When parents can’t enroll their children in healthcare programs online because it is more important to protect clerical jobs, the humane purposes of the welfare state are mocked. When teachers unions proudly commend themselves for making it effectively impossible for schools to discipline or fire faculty members who are burnouts and creeps, the endless, cynical talk about putting children first becomes an indictment. If the rhetoric determined the reality of the welfare state, the needs of its clients would always take precedence over the demands of its personnel. It is a scandal that the politicians who ought to be most deeply concerned about using California’s tax dollars as efficiently as possible to assist the state’s neediest residents are, instead, complacent and often insistent about diverting billions of those dollars to the government workforce. The misgovernment of California has such deep, tangled roots that the anger this scandal engenders will not suffice to rectify it. If that anger is wedded to a determined commitment to reclaim California’s government for its people, that mission may yet succeed.

This essay is part of the Taube American Values Series, made possible by the Taube Family Foundation.

* * *

For Correspondence on this essay, click here.