Apolitical party that allows 17 candidates to compete for its presidential nomination is not a serious political party. A political party that allows its would-be presidents to debate one another silly—and I mean that in every sense of the term—is failing in its job, too. Happily, the number of GOP debates was down from 2012 (when there were 27 of one kind or another); but the number of candidates was up. You may recall that in the early exchanges they answered and evaded questions in flying squads of ten and seven, no existing stage being able to hold them all at once.

Despite the Republican Party’s fatuous and grueling process, however, the voters learned some valuable things. The vast field contained many accomplished politicians, few truly distinguished ones; the senators (Cruz, Graham, Paul, Rubio, Santorum) were young or implausible, the governors (Bush, Christie, Jindal, Gilmore, Huckabee, Kasich, Pataki, Perry, Walker) successful but too numerous, stale, or busy for their own good. There was not the man of “continental character” that the framers had hoped would stand out. That left the “outsiders” or amateur politicians (Carson, Fiorina, Trump).

The governors, with their records of domestic reform, dominated the early betting. As foreign policy issues (Russia, China, and the Middle East) flared up and the primaries began, the senators (except Rand Paul) enjoyed a surge. Only Kasich made it out of the governors’ group; only Cruz and Rubio emerged from the senators; and the outsiders set the tone for the whole cycle. Dr. Ben Carson and businessman Donald J. Trump sat atop the polls for months. Carson’s support finally melted away, leaving Cruz and Rubio (ignoring Kasich, as non-Ohio voters tended to do) to battle for the honor of saving the party from Trump.

Cruz outlasted Rubio, but in the end the man he had patronized for months as “my friend Donald” defeated him handily. Trump defeated them all handily.

Conservative Minds

What, if anything, can conservatives learn from Trump and from this episode? What, if anything, could he learn from us for the fights ahead…always assuming that he is willing to learn? To find out, conservatives will have to engage him. The Never Trump movement may be an understandable, even honorable reaction to the startling victory of a Johnny-come-lately Republican who never enjoyed a deep allegiance to the conservative movement. But it is hardly an adequate one. Conservatives care too much about the party and the country to wash our hands of this election. A third-party bid would be quixotic. That leaves taking the measure of Trump, and offering advice and help, whether or not he has the sense to take it. Conservatives’ duty, in the last case, includes taking precautions, too, to the extent possible, against the possibilities of betrayal or failure that cannot be ruled out in any untested presidential office-holder and especially in this one.

To abstain in 2016, in hopes of stimulating a recovery of full-throated conservatism in 2020, is sheer desperation, ignoring the weaknesses in the multiple forms of doctrinaire conservatism on offer in this cycle: libertarianism (Paul), social conservatism (Huckabee, Santorum, Carson, Jindal), compassionate conservatism (Bush, Kasich), “reform” (Rubio), neoconservative foreign policy (Graham), self-styled “true” conservatism (Cruz). None succeeded in capturing the Republican imagination.

Trump helped to expose some of the problems latent in the current conservative movement and its agenda—without necessarily solving any of them. Aging baby-boomer conservatives are not that interested in sweeping reforms of Social Security, despite Chris Christie’s admirable plan; and the candidates’ evasiveness on how they would “replace” Obamacare, while hardly noble, is entirely understandable, given how difficult it will be just to keep the promises made by the pre-Obama welfare state, much less those added by a post-Obama one. (Trump finessed the problem by simply declaring Social Security and Medicare off limits to cuts, and pledging to unleash an American economy dynamic enough to grow us out of the problem.)

Ted Cruz’s proposal to abolish the Internal Revenue Service fit the pattern: face large and intractable problems like the cost of government and the national debt by proposing a large and utopian solution to a different problem. No one expected Cruz’s plan to be enacted, of course. It was a symbolic affirmation of “true” conservatism, just like the government shutdown. In general, many conservative “solutions” floated untethered from any political strategy that could have gathered sufficient popular and legislative support to enact them. It is always tempting for politicians to will the ends without willing the means. Only in our age do we call this idealism, however, or, in Cruz’s favorite formulation, devotion to principle.

His case is perhaps the most interesting. It was Cruz, more than any other Republican, who throughout 2014 and 2015 led the populist revolt against the party leadership, exhorting the conservative rank-and-file to distrust, despise, and depose the party’s grandees. It must be admitted that the leaders were of considerable help to him. Still, in 2014 the GOP won historic victories in the Senate, in the House, and especially in state governorships and legislative seats. These wins could have been interpreted, with a little moderation and a few tactical victories, as downpayment, as preparation for the coup de grâce to be administered to the Democrats in 2016. Instead, expectations soared and crashed, embittering relations within the party and leading to a kind of crisis of legitimacy. This, in turn, prepared the way for an outsider, who turned out to be not Cruz but Trump.

Cruz Control

Cruz helped to breed his own nemesis. And what does he have to show for it? Is his style of “true” conservatism now the more popular, the more compelling, the better understood? For someone so intelligent and so renowned as a debater, it’s hard to remember any of Cruz’s arguments. Admittedly, he was debating legions of opponents—a case where party leaders really did let the good candidates down, as mentioned above. Partly, however, his fluent arguments lacked a center, a focus.

He had two rhetorical modes—the preacher and the debater. One was earnest and revivalist, summoning ultimate appeals to right and wrong, salvation and damnation; the other was ceremonial, lawyerly, and dazzling, full of cut-and-thrust and aiming at applause and victory. Neither was presidential, strictly speaking, because the president doesn’t preach and never has to debate anyone, at least officially. Cruz needed a third style, more deliberative and suited to fellow citizens. He needed to unite the principles of right and wrong with calm, deliberative judgments about what is advantageous for Americans to do here and now. In that way he—and the conservative movement—could help to cultivate what Abraham Lincoln called a “philosophical public opinion.” Instead, Cruz let his forensic victories demarcate the boundaries of true conservatism—a string of positions each slightly to the right of his main competitors.

Like Marco Rubio, Cruz entered national politics as a champion of the Tea Party. He shared the Tea Party’s longing to return American politics to some constitutional limits, an important and altogether laudable principle. But neither he nor Rubio (nor, needless to say, any of the party elders) turned that vague longing into a compelling political case for an essential agenda. If the Constitution actually were imperiled, wouldn’t you expect this to be the highest and probably most urgent message to voters? Yet restoring the Constitution remained a series of talking points (more elaborate in Cruz’s speeches than in anyone else’s, granted) rather than an organizing cause around which the conservative movement might reinterpret and realign itself. Doubtless, Rubio and Cruz would have picked federal judges with the Tea Party’s concerns in mind. But decades of experience have proved that it takes more than one branch to halt, much less reverse, the constitutional decay, and that the judiciary needs support, pressure, and direction from public opinion and the political branches in order to do its part under these circumstances.

This failure to take seriously the Tea Party’s warning that corruption had eaten deeply into constitutional foundations, and that government was slipping beyond the control of the governed, left conservatives and Republicans searching, as usual, for a purpose. The sense of a dead end was reinforced by Chief Justice John Roberts’s tortuous decisions saving Obamacare, twice, in 2012 and 2015.

If relimiting the government by constitutional means was not an option, said, in effect, a lot of indignant Republican and independent voters, then what is left but to use the system as it is, and try placing a strong leader, one of our own, someone who can get something done in our interest, at the head of it? After the Tea Party, the next stop on the populist train was Trump Tower.

The Trump Business

There is no shortage of reasons to object to Donald Trump. They range from the aesthetic (that hair!) to the moral, political, and intellectual. But there’s no reason to exaggerate. He is not a Caesar figure, though some conservatives sincerely fear that in him. Caesar’s soul was ruled, said Cicero, by libido dominandi, the lust for mastery or domination. Trump wants to make great deals, build beautiful buildings, and shine in the public eye as a kind of benefactor. You might say he is interested in magnificence, not magnanimity. For good or ill, he lacks the deeply political soul. In a 1990 interview, Playboy asked him about his role models from history. “I could say Winston Churchill,” he said, “but…I’ve always thought that Louis B. Mayer led the ultimate life, that Flo Ziegfeld led the ultimate life, that men like Darryl Zanuck and Harry Cohn did some creative and beautiful things. The ultimate job for me would have been running MGM in the ’30s and ’40s—pre-television.”

Trump is a very American character, a very New York character, the businessman who understands the world: the sophos who could bring efficiency, toughness (his favorite quality), and common sense to politics, if only he were listened to. In most of the world, populism is associated with distrust of business, with hatred of capitalism. In the U.S., it’s more common to find populism linked to an admiration for the farmer and small businessman, for the entrepreneur who has pioneered new products and markets, or for the independent businessman who has fairly earned his own fortune. That’s why Trump plays to a familiar Republican fantasy: the business leader who with cost control and double-entry bookkeeping could set government right.

It didn’t work out so well for Herbert Hoover, Wendell Willkie, Ross Perot, Mitt Romney, Meg Whitman, or the many others who tried it at the national or state level, however, because politics is actually quite different from business. For instance, there is hardly anyone to whom the president of the United States can say, “You’re fired.” He is pretty much stuck with the millions of federal employees already hired and protected by civil service, not to mention the judges and elected legislators.

Plus a businessman’s instinct is to want to measure government’s effectiveness by some single, or at any rate straightforward, standard, as a corporation can be measured by profitability, or a stock by earnings per share. But there is no comparable metric for politics that is so revealing and useful. The different branches have distinct powers and qualities (energy, deliberation, judiciousness, etc.), and the qualified independence that comes with them, for a reason. The temptation to be a political Louis B. Mayer, to produce the whole political show and insist on having control over all aspects of it, can lead only to a very frustrated presidency.

Cultural Decline

Of course, Trump’s own business record is indistinguishable from his career as a celebrity. He stubbornly defends his crudity, anger, and egotism as integral to the Trump brand, which he promotes incessantly, and as in touch with the working class voters he covets. To conservatives enamored of the gentlemanly manners of Ronald Reagan and the Bushes, this indecency offends.

Yet it hasn’t disqualified Trump as a candidate, because it helps to certify him as a non-politician, a truth-speaker, and an entertainer. Trump seems to know the contemporary working class well, its hardships, moral dislocations, and resentments. Readers familiar with the new working class described by Charles Murray in Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960–2010 (reviewed in the Summer 2012 CRB) will have a roadmap to the America that Trump sees and rallies to his side. As the Obama team got a jump on its rivals by exploiting new campaign software and technology in the 2008 race, so Trump got a cultural jump on his rivals in the 2016 primaries. He saw that the older, politer, less straitened America was fading among the working and lower middle classes. Downward mobility, broken families, disability and other forms of welfare support—these were increasingly the new reality for them.

This left them lots of time for TV (as Murray shows), especially for reality TV shows. Trump was more in touch with these developments, and also with the anxieties of the working part of the working class who feared falling into this slough of despond, than any of the other candidates. To put it in business speak, as the New York Times did, Trump “understood the Republican Party’s customers better than its leaders did.” It didn’t help that much of the rank-and-file had lost confidence in those leaders. Trump ran rings around them, and employed new media to do it. Steve Case, the founder of AOL, described that part of the achievement in an email to the Times that had the odd rhythm of one of its subject’s tweets. “Trump leveraged a perfect storm. A combo of social media (big following), brand (celebrity figure), creativity (pithy tweets), speed/timeliness (dominating news cycles).”

Every republic eventually faces what might be called the Weimar problem. Has the national culture, popular and elite, deteriorated so much that the virtues necessary to sustain republican government are no longer viable? America is not there yet, though when 40% of children are born out of wedlock it is not too early to wonder. What about when Donald Trump is the Republican nominee for president? Many conservatives think that’s also sufficient reason to worry the end is near.

I understand the question, but the surer sign of comprehensive decline is not Trump’s success but the conservative candidates’ failure, one by one, all 16 of them. Trump himself has formidable, late-blooming political talents, and his vices have been exhaustively condemned but never examined in comparative perspective. Do obscenities fall from his lips more readily than they did from Lyndon Johnson’s or Richard Nixon’s? Are the circumstances of his three marriages more shameful than the circumstances of John F. Kennedy’s pathologically unfaithful one—or for that matter, Bill Clinton’s humiliatingly unfaithful one? Have any of his egotistical excesses rivaled Andrew Jackson’s killing a man in a duel over a horse racing bet and an insult to Jackson’s wife? The point is not to extenuate Trump’s faults but to understand how millions of voters see him. They know he is damaged goods, just as the Clintons are—and were, even in 1992—but they apparently regard him as more trustworthy or at least more faithful to their interests than any of his GOP competitors.

One difference is that Johnson’s, Nixon’s, and Kennedy’s sins were mostly kept behind closed doors. The culture in those days was intolerant of such vices (Nelson Rockefeller is the exception that proves the rule); our culture, not so much. Trump is not the first to benefit from our lower religious and moral standards—that would be the Clintons—and though his excesses shouldn’t be condoned, most voters (so far) don’t regard them, as Trump himself might say, as deal-breakers.

President Trump

The worst thing about the Trump phenomenon is that he does not spend his days and nights conscientiously preparing for a job for which everyone—everyone—agrees he is conspicuously unready. People seem to be hoping, praying (more, please) that he is a quick learner. After the initial exhilaration of office, he will probably be bewildered, frustrated, and unhappy; bored, in time. It’s hard to say, of course, because he has never held elective office of any sort. Perhaps his inner statesman will emerge. Judging from the sweeping things that in his speeches and interviews he asserts a president can do, however, incipient statesmanship does not seem to be in the cards.

Separation of powers, federalism, and the numerous other formal and informal folkways of American government seem likely to constrain a President Trump in ways that will surprise him (while delighting others) and to which, all signs indicate, he has given very little thought. In his emphasis on getting things done by negotiating great deals between the branches, he sounds a little like Richard Neustadt, the political scientist who found the essence of presidential power not in the official powers and duties vested by the Constitution but in the president’s personal ability to persuade. Although Neustadt, a Harvard professor, meant persuade in a more high-minded way than Trump does (The Art of the Deal says it all), Trump’s raw understanding of the presidency appears nevertheless to lie much closer to the liberal tradition stemming ultimately from Woodrow Wilson and Teddy Roosevelt than to the conservative or constitutionalist one. Wilson, not Trump, said this:

The President is at liberty…to be as big a man as he can. His capacity will set the limit; and if Congress be overborne by him, it will be no fault of the makers of the Constitution—it will be from no lack of constitutional powers on its part, but only because the President has the nation behind him, and Congress has not.

Though Wilson reassured his readers that “the reprobation of all good men will always overwhelm [immoral or dishonest] influence,” he stressed at the same time that “the personal force of the President is perfectly constitutional to any extent which he chooses to exercise it.” “Personal force”—not far from Trump’s praise of high energy, toughness, and strength in the ideal chief executive.

The big difference between Wilson’s theory and Trump’s reality, however, arises from the role of the political party. Wilson assumed that to be an effective leader of the nation, the president would first have to be a spirited leader of his own political party, organized around his own dominating vision. Trump has plenty of vision, but in all likelihood his political party, or at least a large segment of it, will be estranged from him. He may come close to being a president caught between two parties, each suspicious of him and hostile to him to varying degrees. This is the recipe for a weak presidency, like Andrew Johnson’s after the Civil War, as James Ceaser and Oliver Ward pointed out recently in the Weekly Standard. Bluster is no substitute for a party platform, personal predilections for a well-developed administration agenda.

Again, it is not the overbearing executive so much as the haphazard one, adrift much of the time, that is the risk. The two are not as opposed as they seem, inasmuch as it is the erratic, unsteady leader who is often tempted to lash out to try to rescue the situation. Think Arnold Schwarzenegger in California, or Jesse “the Body” Ventura in Minnesota. (Trump had his own involvement with WWE for a while through his New Jersey casinos.) Though perhaps more serious about his politics than these two, Trump is likely to prove less involved than Silvio Berlusconi in Italy, also a billionaire media personality with a brand. Berlusconi was deeply anti-Communist, a four-time prime minister, and the founder of two political parties (Forza Italia and The People of Freedom). Trump thinks of himself as a man above party, or outside of party. His favorite metaphors come from boxing—not a team sport.

How will these divergent vectors resolve themselves into a coherent presidency? There is no guarantee they will, but to the extent he could find a model to suit him, the best might be his fellow New Yorker, Theodore Roosevelt. Keep your eyes open for a T.R. boomlet in Trump’s future.

Political Correctness

It’s no coincidence that the two loudest, most consequential socio-political forces in America right now are Political Correctness and Donald Trump. One is at home on college campuses, the other in the world of working people. Yet they are already beginning to collide. At Emory University recently, someone scrawled “Trump 2016” in chalk on steps and sidewalks around the campus. About 50 students swiftly assembled to protest the outrage, shouting, “You are not listening! Come speak to us, we are in pain!” Aghast at “the chalkings,” the university president complied.

At Scripps College, just a few weeks ago, a Mexican-American student awoke to find “#trump2016” written on the whiteboard on her door. The student body president, in a mass email, quickly condemned the “racist incident” and denounced Trump’s hashtag as a symbol of violence and a “testament that racism continues to be an undeniable problem and alarming threat on our campuses.” The student body’s response, apparently, was underwhelming. Shortly the dean of students weighed in with an email of her own, upbraiding students who thought the student body president’s email had been, oh, an overreaction. The dean noted that although Scripps of course respects its students’ First Amendment rights, in this case the “circumstances here are unique.” Note to dean: the circumstances are always unique.

The brave student journalist from whose account I take the Scripps story, Sophie Mann (who, incidentally, has taken two courses with me), closed her post in the Weekly Standard with this eye-opening statement: “In any event, I am hoping that this dies down before finals, because last semester, in the face of radical student agitation over minority victimization here, the student-run coffee shop was declared a ‘safe space’ for minority students. That was hard on those of us who need caffeine to study.’” Translation: the coffee shop was closed for several days to white students, who were officially forbidden its use, so that “students of color” could enjoy it safe from “white privilege” and oppression.

When P.C. world and Trump world collide, as these preliminary incidents show, there will be blood, or at least chalkings and coffee deprivation. In all seriousness, it’s likely that the campuses will erupt this fall in political disturbances of a sort not seen since the early 1980s—not out of affection for Hillary Clinton but out of fear and loathing of Trump. If he is elected, the next four years may be one long demonstration, perhaps rivaling the ’60s.

But the troubles won’t be confined to the campuses. The Left has gotten used to the way it runs the universities—by a powerful, ideological majority so dominant that there isn’t usually any effective opposition, or any opposition at all. What else can you expect when, as a study of 11 California colleges found, among sociology professors Democrats outnumber Republicans 44 to 1? In most other departments (except, e.g., economics), Republicans are outnumbered by ratios ranging from 5-16 to 1. Republicans are much rarer than any of the groups usually singled out for affirmative action or other special admissions attention. Except for Jonathan Haidt and a handful of others, when did liberals ever complain about this imbalance?

The truth is they enjoy it; they regard it as natural, advantageous for students, and, increasingly, as a model for how the rest of the world should be run. What’s worse is what they routinely do with their extraordinary power: they distribute benefits and rights by race, sex, gender, politics, and ethnicity, as the coffee house example illustrates. On campus, the shock troops, victims, counselors, and administrators are introduced to their roles and prepared to fulfill their functions inside and outside the university: to order atonement and punishment, distribute rights and duties, assign equality and inequality, police the boundaries of speech, decide who may be offended and by whom and for how long and why.

This is political correctness, and it is now the first of the Left’s political institutions. It marks a new, ugly stage in liberalism, a new ensemble of required moral attitudes, as even a few sensitive liberals (e.g., Jonathan Chait) have begun to recognize and criticize.

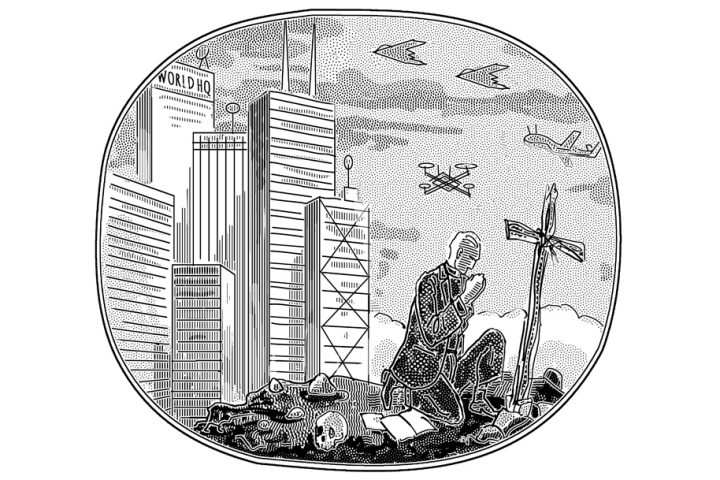

Political correctness is a serious and totalist politics, aspiring to open the equivalent of a vast reeducation camp for the millions of defective Americans who are products of racism, sexism, classism, and so forth. This is most conveniently accomplished on college campuses, where few people expect toleration or civil equality these days; but it can also take place in police departments, coal mines, the human resources divisions of major corporations, on social media, and in political campaigns.

It’s the basso profundo under the Left’s anti-Trump argument. Hillary’s criticism that he is “a loose cannon” arouses many fears—foreign policy blunders, the nuclear keys—but running underneath them, sostenuto, is the fear and outrage that he is always prepared to say things that offend a group that must not be offended. Debbie Wasserman-Schultz, the head of the Democratic National Committee, got to the heart of the matter when she tweeted, “Trump’s racism knows no bounds,” where “racism” is the Left’s all-purpose condemnation for political incorrectness.

P.C. is the hard edge, the business end of what Emmett Rensin, on Vox.com, has called “the smug style” in American liberalism. Ever since the Democrats lost the working class, he argues, they signed their souls over to “the educated, the coastal, and the professional” classes. These overlords invented the smug style to answer the question, “What’s the matter with Kansas?” as Thomas Frank titled his 2004 book, or more generally, How could the working class vote against its own obvious (to a liberal) economic interest? The answer: “Stupid hicks don’t know what’s good for them.” In this view, conservatism is not an attractive set of arguments or principles but a form of stupidity, of unknowing. Liberalism, by contrast, is a form of shared “knowing,” based not on knowledge, exactly, but on the presumption of knowledge. Hence the smug “knowingness” of the contemporary Left, most apparent and irritating in its smug contempt for working people who have rejected it.

Though his is a relatively mild case, President Obama cannot hide his smugness. As you may have noticed, the American people often disappoint him, clinging to their God and guns instead of cheering for his policies. No previous president except Woodrow Wilson suffered from this brand of arrogance. Consider, for example, how quickly and shamelessly Obama switched from opposing to supporting gay marriage. The only thing like it was how blithely the liberals on the Supreme Court pulled their switcheroo, assuring us that only bigotry—not a shred of common sense or natural-law humanism—could ever have justified a prohibition on same-sex marriages. Obama almost winked at the American public: you knew all along I really wasn’t against it, didn’t you?

Incorrect, and Proud of It

It’s the spirited way Donald Trump has defied the P.C. mavens, I think, that’s been the key to his success so far. On the policy questions he has taken a few conspicuous stands—immigration, trade, ISIS and the Muslims, foreign alliances—that he has more or less stuck to, though even on these he has advertised his flexibility. The “beautiful wall” he’s going to build on the Mexican border will also have “beautiful doors” for good Mexicans to stroll through into the U.S., for instance. On close analysis his tough stands appear strikingly tactical, which is why those commentators who have mistaken him for a Truman Democrat or an old-fashioned liberal Republican (especially on entitlements) are not entirely wrong. Unlike Cruz, Bush, and his other competitors, Trump has seemed to treat the content of his policies as a second-order question, which is why they have been so undetailed so far. The crucial thing for him, at least at this stage of the campaign, is to stake out a tough position in tough terms, to be as politically incorrect as possible on his selected issues.

In this respect, being anti-P.C. has, from the start, been the central point of his campaign. It proved a brilliant decision. The other Republican contenders might have done the same thing, but they were in thrall to their own versions of conservatism and the attendant policy agendas. They couldn’t see that in 2016 the ascendance of P.C. liberalism raised issues more fundamental, principled, and passionate than the think-tank-approved litanies of tax, spending, and foreign policy reforms. Trump alone was willing, eager even, to embody political incorrectness, to own it, not merely to patronize it. And most politically incorrect of all, he got people to laugh with him as he did it.

This is an election, Trump bet, more like 1968 than like 1980. Like Richard Nixon in ’68—an admirer of Teddy Roosevelt, by the way—Trump felt that this election might test whether the center could hold, whether a silent majority could be mobilized on behalf of the country itself. The issue was not so much a showdown over liberal or conservative policies, but the simpler, more elementary question of whether a majority still wanted America to be great again. Trump is more devisive than Nixon was, but perhaps he thinks the country is in worse shape, and that the majority needs to be angry, not silent.

Reaganism came with a full complement of urgent and intelligent policies. Nixon really had no -ism; he thought the times demanded improvisation in the interest of conserving the nation, the only kind of conservatism he really respected. Trump is closer to Nixon. He is in no hurry to build out Trumpism into a political doctrine.

If there were a core to Trumpism, however, it would be his insistence on “America First,” a phrase with unfortunate connotations, to say the least. To him, though, it seems to mean the legitimacy of preferring one’s own people or country to others. Charity begins at home, in other words. The Declaration of Independence, notably, pays “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind” and appeals to “the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions,” but it speaks only “in the name, and by authority of the good people of these Colonies.” The Constitution is designed to “secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our Posterity” (emphasis added). It is not at all inconsistent with human rights to take care of your own first, and in fact it is a duty to ward off tyranny for one’s own people before attending, to the extent possible, to others. By 1939, of course, farsighted statesmen could see already that the storm of war would almost certainly hit America, second, and soon.

Trump hasn’t fleshed this out, alas, and he rarely mentions the Constitution or America’s founding principles. That is shortsighted and a mistake. Who knows if he will correct it. If he did, he could broaden the discussion from the mores of the Mexicans to the mores of the Americans—“Americanization” being necessary for legal immigrants as well as for the native born—which is the ultimate concern. But his savvy opposition to P.C. implies something like this defense of America, because there is nothing political correctness stands for so much as the denigration of America, its history and principles. P.C. liberalism doesn’t stop there; its hostility extends to the theological, philosophical, literary, and scientific heritage of the West. But freedom, too, begins at home.

It is one thing to oppose so-called political correctness. It is another, and even more important, thing, to specify and defend what is actually politically and morally correct. Incorrectness can in today’s context include anything from simple rudeness to Lincolnian first principles. We know pretty well what Donald Trump is against. He will not have much time to decide what he is for.