Books Reviewed

If you find your Amazon expenditures exceeding your budget each month, take heart: great-souled men are no penny-pinchers.

That’s a proposition amply demonstrated in this book by first-time author David Lough, which offers an entertaining look at Winston Churchill’s life from an entirely new angle: the great statesman’s personal finances.

Lough’s title is a bit misleading. True, in a moment of apparent retrenchment, Churchill did tell his wife that they had to cut out the bubbly. But the prohibition seems never to have gone into effect. Even during the Depression, when he was on the back bench politically and losing tens of thousands of dollars in the American stock market, Churchill consumed at least five half-bottles of champagne a week. For lunch. With oysters.

By profession Lough is a financial advisor. I too have spent much of the last 20 years advising some of the wealthiest individuals and families around the globe. Typically, their extravagances resemble the sort that Churchill encountered in his late-in-life association with Aristotle Onassis, who gave the Churchills several cruises on his 325-foot yacht, Christina. On board Churchill found lapis-lazuli baths, jade and gold icons, onyx tables, and a glass-topped bar with models of ships sailing beneath: the conspicuous consumption of the first-generation wealth-creator.

Churchill’s spending aimed at pleasure rather than show. He came from well-heeled families on both sides, but his parents managed to deplete most of their resources. Yet from an early age Winston excelled in overdrawing his bank account on fine wine and spirits, clothes, and, of course, cigars. Nor was this just boyish excess. During the single month of May 1949 (when Churchill was 74), his household consumed 36 bottles of whisky (Black Label), 38 bottles of port, and no less than 95 bottles of Pol Roger champagne. It is no wonder that upon his death in 1965, Madame Odette Pol-Roger “instructed that a black band of mourning” be placed around the family label.

To pay for these delicacies Churchill’s first resort was to borrow. He fully tapped private banks Cox & Co. and Lloyds. When he played the stock markets he often did so on a 100% margin. He borrowed as much as he could from the trust set up under his father’s estate. (He could not get at the principal, as it was designated for his children.) He kept tabs running, sometimes for years, with his lawyers, clothiers, cigar makers, and above all his wine merchant.

* * *

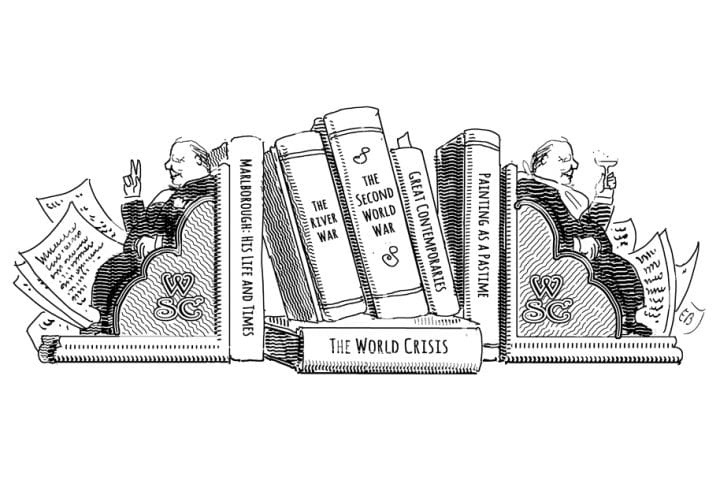

But borrowing alone would not have taken Churchill far. And so he made the most of his formidable intellectual capital. Lough’s book is as much an account of Churchill’s prolific publishing as it is a story of his prodigious spending. Churchill began by making five or ten pounds an article writing from the front lines of the Spanish-American War in Cuba, or on the march to Khartoum in the Sudan. His real break was the Boer War, which won him a salary of over £1,000 from the Morning Post. His epic treatment of the Great War—The World Crisis—and his biography of his famous ancestor, Marlborough: His Life and Times, were commercial successes. He liberally used “his” state papers to support his writing, particularly of his final memoirs, The Second World War, which earned over half a million pounds.

A less public part of Churchill’s economic life, which Lough narrates with the verve of a prizefight, is his many-decade struggle against the taxman. As a young author and M.P., Churchill seemed content to pay his roughly 20% income tax. But as his income grew, and as the marginal rate rose—first to over 50% during World War I and then to 97.5% during World War II—Churchill spent immense energies avoiding taxes. His main strategy was to make sure that his payments for writing were treated as capital gains, for which there was no tax at the time. Also, during his times as a minister, Churchill declared himself a “retired author,” which shielded any income he received in his “retirement.”

* * *

Churchill’s brushes with bankruptcy, taxes, and wealth make a charming story. But it can also feel at times like an ant’s-eye view of an elephant: negotiations over loans or book contracts occupy page after page, while the Dardanelles campaign or the Battle of Britain flits by in a paragraph or two.

Besides its novelty, however, the advantage of Lough’s focus is that it allows one to revisit the old question of whether the art of political rule and the art of household management are one and the same. The political tone-deafness of many businessmen, the economic illiteracy of many politicians, and the divergence of political science and economics all suggest they are not. But perhaps the sort of man who can smoothly keep his creditors at bay, convince publishers to pay him millions for his thoughts, and enjoy the private pleasures to their fullest is just the sort who can also rebuild a country’s military might, rally a people in despair, and remind others what’s truly worth fighting for.