There are no Reconstruction re-enactors. And who would want to be? Reconstruction is the disappointing epilogue to the American Civil War, a sort of Grimm fairy tale stepchild of the war and the ugly duckling of American history. Even Abraham Lincoln was uneasy at using the word “reconstruction”—he qualified it with add-ons like “what is called reconstruction” or “a plan of reconstruction (as the phrase goes)”—and preferred to speak of the “re-inauguration of the national authority” or the need to “re-inaugurate loyal state governments.” Unlike the drama of the war years, Reconstruction has no official starting or ending date. Although we usually bookend the period with the Confederate surrender in 1865 and the withdrawal of federal occupation troops in 1877, people had been talking about “reconstruction” even before the shooting began in 1861, and the federal occupation troops who were withdrawn in 1877 were by that time little more than a corporal’s guard. In some sense, Reconstruction ended when Democrats managed to regain control of the House of Representatives in 1874; other parts of it spluttered on till the appearance of Jim Crow in the 1890s and Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896.

Even more difficult than sticking dates on it, Reconstruction is difficult to grade. The best that has been said for it was that it was “unfinished”; the worst that it was a “mistake.” Yet, in its most fundamental sense, Reconstruction was actually a surprising success. The secessionist regimes in the Southern states were deposed, new federally-supervised governments were put in their place, and one-by-one the rebel states were restored to the Union—which is to say, they sent representatives and senators to Congress, acknowledged federal laws passed by Congress, and obeyed the federal military and civilian institutions which implemented them. Military occupation, marvelled the North American Review in 1872, was managed with a mild hand, deploying “out of the reduced army of thirty thousand men” that remained after postwar demobilization in 1865 “only one-tenth for service at the South.” As Walt Whitman wrote, almost in self-congratulation, Reconstruction “has been paralleled nowhere in the world—in any other country on the globe the whole batch of the Confederate leaders would have had their heads cut off.” (Ironically, most of the violence that pockmarked Reconstruction was inflicted on the victors, not the vanquished.)

Take it a step further: if the point of the Civil War was to reestablish a federal Union—a genuinely federal Union in which neither the states nor the federal government claimed exclusive sovereignty, but shared it in a federal system—then Reconstruction should be as much a source of national self-admiration as the Civil War long has been. The next half-century proved to be the Golden Age of constitutional state rights, with states taking up the political initiative in terms of civic reform, women’s rights, and public education long before the federal government ever noticed them.

But that, of course, is not the way Reconstruction has been taught to most of us. For decades, both the hell-no partisans of the Lost Cause and turn-of-the-century Southern Progressives maintained that Reconstruction was a nightmare inflicted on them by a psychotically vengeful coterie of Radical Republicans in Congress led by Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner, and Ben Wade. This view depicts Reconstruction as a kind of Vichy occupation, partly a draconian direct rule by scheming, unscrupulous Northern interlopers called “carpetbaggers,” and partly an unstable domination by Southern turncoats known as “scalawags.” In the work of the then-reigning prince of Reconstruction historians, William A. Dunning, Reconstruction was only temporarily successful, and for all the wrong reasons. It demonstrated the excesses of democracy, especially in giving the vote to freed slaves, and produced what Progressives regarded as the mortal sins of unmanaged government—inefficiency and corruption.

The Dunning School hit its first major opposition in the 1930s, beginning with the attacks launched by W.E.B. Du Bois in Black Reconstruction in America (1935) and James S. Allen (the nom-de-plume of Sol Auerbach) in Reconstruction: The Battle for Democracy (1937). The Dunning School, Du Bois protested, had succeeded in making every “child in the street” believe that “the history of the United States from 1866 to 1876 is something of which the nation ought to be ashamed.” Reconstruction might not have been a proud achievement, but Reconstruction actually set an example “to democratic government and the labor movement today.” Allen agreed: “The destruction of the slave power was the basis for real national unity and the further development of capitalism, which would produce conditions most favorable for the growth of the labor movement.” The Dunningites thought that radical Reconstruction was something to be deplored, and cheered when it failed; the revisionists agreed that it failed, but wept. Southern blacks, in Du Bois’s phrase, “went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back into slavery.”

Unhappily, neither Du Bois nor Allen possessed a broad platform on which to rally a counter-movement. It would not be until the 1960s, after the emergence of the civil rights movement as a “second Reconstruction,” that the idols of the Dunning School really began to fall. John Hope Franklin’s Reconstruction After the Civil War (1961) and Kenneth Stampp’s The Era of Reconstruction, 1865-77 (1965) started the supplanting, followed by John and LaWanda Cox, Richard Current, Allen W. Trelease, and finally by Eric Foner’s massive Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988).

Competing Economies

Noble as their intentions were, the anti-Dunningites had their faults, too. Du Bois, Allen, Stampp, and Foner were writing from self-consciously Marxist frameworks that forbade any other understanding of Reconstruction but through class and revolution, with race sometimes deployed as a surrogate for class. Reconstruction thus became the moment when working-class blacks and whites together had an opportunity to create a new economic and political order in the South. They had been encouraged in this alliance by the so-called bourgeoisie, who saw this rising proletariat as a useful ally in their war against the feudal aristocracy. Alas, as the Marxists saw it, bourgeois revolutions frighten their own architects, since the bourgeoisie are themselves the owners of property—in this case, industrial property—and quickly come to see that in empowering peasants and workers, they have created a Frankenstein monster that has no more respect for the bourgeoisie than it had for the aristocrats. At that moment of self-realization, the bourgeoisie strain to stuff the revolutionary genie back into the lamp from which it was conjured. “The bourgeoisie,” wrote Lenin, “strives to put an end to the bourgeois revolution halfway from its destination, when freedom has been only half won, by a deal with the old authorities and the landlords.” But the genie cannot be stuffed; it is only stunned, and in time it will reawaken with renewed strength as the guide and leader of the socialist revolution, and finish-off industrial capitalism the way the bourgeoisie overthrew the aristocrats. Du Bois in particular bears the impress of this notion of Reconstruction as a bourgeois revolution, for in Du Bois’s telling, Reconstruction’s “vision of democracy across racial lines” was undone by a “counterrevolution of property.”

There are, however, two significant hurdles to accepting this definition of Reconstruction as a conventional “bourgeois revolution.” As historians like James Huston, David Montgomery, and Robert Gordon have shown, the contest which was waged between 1861 and 1865 was not between a Southern mint-julep-sipping aristocracy and a smoke-belching factory capitalism, but between two versions of agrarianism, between the free-labor family farm and the slave-labor cotton plantation. Only in Rhode Island did workers in American factories amount to more than 20% of the population (although Massachusetts was a close second); in the West, the numbers rarely topped 1%. Not until the 20th century would the United States begin to emerge as a genuine industrial power, and with it, an economy which could be clearly demarcated by class conflict.

But a greater problem with the Marxist construct of a bourgeois revolution is that there is no evidence whatsoever that the revolutionaries who essayed to build a bourgeois South ever panicked at the prospect of empowering blacks or poor whites, or betrayed them by establishing a self-protecting alliance with the aristocrats. To the contrary, Reconstruction was a bourgeois revolution that was crushed by the resurgent political power of a bloodied but unbowed aristocracy, establishing alliances of its own with the emerging industrial proletariat of the postwar North.

Free Labor

The goal of abolishing slavery was often not, as we are tempted to see it, a crusade to right a racial injustice; for many Republicans abolishing slavery was not much of a racial question at all, but rather an economic one. The Union “represents the principles of free labor,” declared New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant, and only when “the victory of the Northern society of free labor over the landed monopoly of the Southern aristocracy” was complete would the war be over. In the most basic sense, free labor was simply a shorthand for liberal economic democracy. Among free labor’s fundamental tenets were the encouragement of small-scale manufacturing, especially through government-sponsored “internal improvements” in the form of canals, highways, and railroads; economic mobility, with constant movement up the ladder of classes; and the practice of a constellation of bourgeois virtues—thrift, prudence, industry, religious faith, temperance, rationality, nationalism—which would all tend together to dignify what the New York American described in 1834 as both “the enterprising mechanic, who raises himself by his ingenious labors from the dust and turmoil of his workshop, to an abode of ease and elegance” and “the industrious tradesman, whose patient frugality enables him at last to accumulate enough to forego the duties of the counter and indulge a well-earned leisure.”

In the eyes of the free-labor middle class, the mistake of the South had been to allow the thousand-bale planters to turn the Enlightenment clock backwards to medieval serfdom. “Who knows,” asked the New-York Daily Tribune, “but we may see revived [in the South] the feudal tenures—maiden-right, wardship, baronial robberies, the seizure of white children for the market, military service, and the horrible hardships of villenage which men have fondly deemed forever abolished” as the logical corollaries of slavery. In the South, the ruling class of “monarchists and aristocrats” had shunned government-sponsored improvements, cultivated a style based on braggadocio, and held poor whites and black slaves in the grip of a permanent and oppressive hierarchy. “There labor has been degraded, the laborer left untaught,” warned the Chicago Tribune in 1864, “thus converting half the Union into a charnel house of despotism, without a free religion, free speech, free press or free schools.” The Civil War, however, had swept this “despotism” away, and cleared the path for introducing into the South what Republican Congressman James Campbell called a New England-style “high type” of culture: “the cultivated valley, the peaceful village, the church, the school-house, and thronging cities.” The South “under the old system” was adverse to “manufacturing and commercial enterprises.”

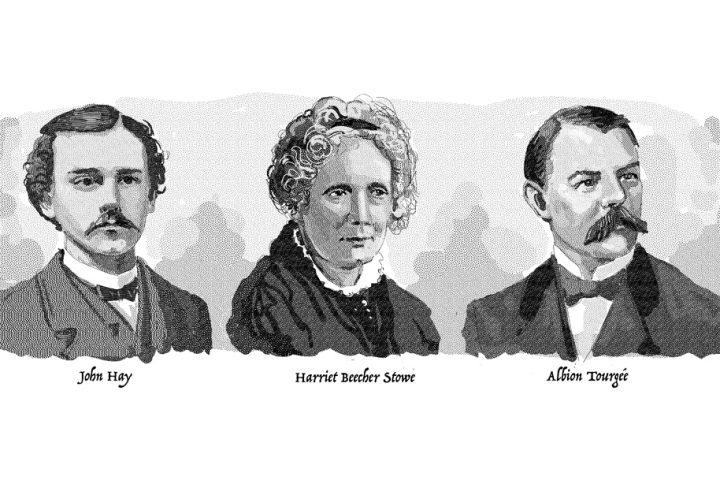

But now, the “tide of free labor” which would rush into the conquered Confederacy “will be incalculable.” The South’s “worn-out plantations will become thriving farms,” rejoiced the Continental Monthly in 1862, “its mines and inexhaustible water-powers will call into play the incessant demand and supply of vigorous industry and active capital.” Reconstruction offered a means of refashioning the entire labor system of the South, provided, wrote Union veteran Albion Tourgée, that the South was “desouthernized and thoroughly nationalized.” Tourgée was an example of how eager Northerners were to help this process along. Born in Ohio and educated in New York, he had served in the 105th Ohio, endured the sufferings of Libby Prison as a prisoner-of-war, and settled in Greensboro, North Carolina, at the end of the war in order to find relief in a warmer climate for a wound that had damaged his spine. He opened a law office and became president of a small wood-handle business, the Snow Turning Company, whose success left him “perfectly thunderstruck at the profits” as well as the good wages paid to its largely black workforce. John Hay, who had been Lincoln’s private secretary, was another example. Hay had been sent in 1864 to register Southerners willing to take the oath of allegiance, and came away sufficiently intrigued by Florida (“It is the only thing that smells of the Original Eden on the Continent”) that he bought land to grow oranges near St. Augustine. Even Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, bought orange groves near Jacksonville, moved South, and created a free-labor colony around the village of Mandarin. “People came hither from the North,” wrote a New Orleans contributor to DeBow’s Review, “with the idea that they were coming to an El Dorado, where fortunes were to be gained in a day.”

Here was a real bourgeois revolution—not in the Marxist sense of being a necessary footstool to the “real” proletarian revolution—but an Enlightenment counter-revolution against what the Northern middle classes feared might be the real wave of the future: the Romantic renascence of oligarchy and monarchy.

Lost Cause

The principal obstacle to realizing this dream was the refusal of the defeated Southern planter class to admit that it had been defeated, for that class had by no means been swept away by the war. They, too, had lived by a set of presuppositions, but one based on a general suspicion of middle class ambitions. “The typical Southerner,” feared a contributor to the Atlantic Monthly, “possessed a…cast of character which was founded mainly on family, distinction, social culture, exemption from toil, and command over the lives and fortunes of his underlings.” Not only the culture of the South, but its physical circumstances, too, helped sustain its recalcitrant feudalism. The South owned only 12% of the nation’s mills and factories, and employed as laborers in those establishments only 7% of its population. Cotton agriculture remained after 1865, as it had been before the war, the producer of the United States’s single most valuable export commodity (some 32% of all exports as late as 1889). And no wonder: while commodity prices for wheat, corn, and coal had operated (except for the war years) within fairly narrow ranges, cotton was selling above all its pre-war highs; in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas cotton acreage and production expanded, employing a black labor force indistinguishable from that under slavery. Great Britain in the decade after the Civil War still bought 58% of the cotton it imported for textile manufacturing from the United States, and that would continue to rise through 1876.

Despite the economic impoverishment imposed on the South by the war and the legal abolition of slavery, the patterns of economic production remained remarkably unchanged. In western Alabama’s “black belt,” 236 landowners possessed at least $10,000 in real estate in 1860 (with the median landholding amounting to 1600 acres); 101 of those landowners were still in possession in 1870—which was about the same rate of persistence over time which had prevailed before the war. And it was noticeable that, outside the principal cities, the great marker of a free economy—the use of cash as a medium of exchange—entered only fitfully into Southern calculations. The New York Cash Store in Greenville, Alabama, advertised (despite its name) that “we will take in exchange for goods, country produce, particularly Eggs, Chickens, Bees Wax, Dry Hides, Peas, Corn Meal, and anything else that we can dispose of.”

Former slaveholders, thanks in large measure to President Andrew Johnson’s amnesties and the failure to break up or even confiscate rebel land-holdings, were thus free to use cotton profits to maintain a version of the plantation system, closing off opportunities for the newly freed slaves to acquire land and forcing them into peonage. “The relation of master and slave no longer exists here,” wrote one Mississippi valley planter, “but out of it has evolved that of patron and retainer,” which was a far cry from “one purely of business” or “the ordinary relation of landlord and tenant or of employer and employee.” Slavery might have been legally dead, but it was only being replaced by hutted serfdom.

Northern free-labor apostles grew discouraged at the poor inroads they had made on Southern culture, and went home, disillusioned. They were, sighed Charles Gayarré in the North American Review in 1877, only “merchants, shopkeepers, mechanics, manufacturers, speculators, brokers, bankers” and not “barons after the fashion of the South.” They were subject to harrassment, shunning and violence, and stigmatized as “carpetbaggers.” Leander Bigger, an Ohioan who moved to South Carolina after service in the Union army, described the burning of a store he owned west of Manning, South Carolina, where the chief offense seemed to have been his willingness to extend credit to black farmers trying to set up on their own:

They ransacked the store…. All my dry goods—everything that was combustible—they took out into the square, and took a keg of powder that I kept in a concealed place…piled the goods over it, and set the pile on fire. The goods, being calicoes, muslins, and delains, burnt slowly. They carried us up to the fire, and the speaker (they gave all their orders by signals) ordered his men to mount. They mounted their horses, formed in line, and then the speaker came up to me and told me, “You must quit business. This is only a warning: the next time we will put you on the fire.” …He said he was from hell and represented the devil; that he would take me with him if I did not obey orders.

And no wonder: Southern elites saw little in the free-labor ideology they wanted to embrace. Northerners remained as “effeminate, selfish, most unscrupulously grasping” as ever, declared the Southern novelist Augusta Jane Evans in 1867; even their children were “pitiable manikins already chanting praises to the Gold Calf.”

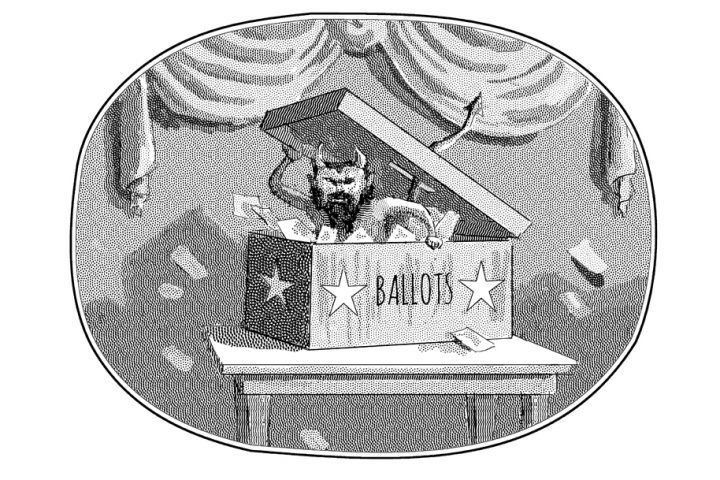

Jim Crow was an anti-free-labor strategy as much as it was a strategy of political exclusion. The freedman “is going to be made a serf, sure as you live,” prophesied one white Alabamian to John Townsend Trowbridge in 1865. “It won’t need any law for that.” When it was pointed out that South Carolina’s “eight box law” (requiring a voter to be able to read the names of candidates and the respective offices they were running-for in order to place the correct ballot in one of eight ballot boxes) would disfranchise poor whites as easily as blacks, the major-general of the South Carolina militia merely replied, “We care not if it does.” South Carolina Republicans protested that this had no other purpose than “keeping the middle classes and the poor whites, together with the negroes, from having anything to do with the elections,” and they were right.

Seeing the Future

Reconstruction aspired to restore the foundations of freedom to a wayward South and it expected to triumph as effortlessly as 19th-century liberal notions of progress had promised. Instead, the same Romantic feudalism that had created the old Southern order reasserted its hegemony, and postwar Southern aristocrats appealed to a set of cultural and racial biases which safely defused the importance of property, and sharply restricted access to it. This might have been averted had the victorious Union been willing to pour the resources into Reconstruction it had devoted to winning the war. But Reconstruction became a symbol of how quickly political fatigue afflicts liberal democracies. Moreover, understanding Reconstruction as a bourgeois revolution which was strangled in its cradle by vengeful cotton nabobs offers some larger parallels to the optimistic era that prevailed between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of Islamic state terrorism.

In his 1989 essay for the National Interest, “The End of History?” political scientist Francis Fukuyama seized on the ignominious collapse of the Soviet system as proof that “the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution” was “the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government” and Marxism’s “death as a living ideology of world historical significance.” That conclusion was, to say the least, premature, not only because it reckoned without the rise of an Islamist theocracy or the fallout from the 2008 worldwide recession, which provoked a renascence of Marxist advocacy in the writings of Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, Alain Badiou, the Occupy Movement, and Thomas Picketty. This pattern is, again, an echo of what happened in Reconstruction, and it warns those who yet believe that liberal democracy is the most desirable political future to be wary of Whiggish assumptions about democracy’s inevitability. Human society has oscillated between desires for stability, security, and reciprocity—which is what feudalism, Marxism, and theocracy promise—and desires for mobility, liberty, and profit—which is what the Enlightenment offered on a world-historical scale. There is nothing that can be declared permanent in a bourgeois revolution, and our own Reconstruction, not to mention a good deal of recent history, is the unhappy proof.