Books Reviewed

My favorite anecdote answering the question in the title of Melissa Moschella’s new book, To Whom Do Children Belong?: Parental Rights, Civic Education, and Children’s Autonomy, involves former Senator Phil Gramm of Texas. Once on a television show, the story goes, he asserted that parents ought to have priority over the state in determining the education of their offspring because they cared more about them than the state ever would. When contradicted by his interlocutor, who apparently insisted that she, too, cared about his children, Gramm replied: “Oh yeah? What are their names?”

This insight—that the parent-child relationship is unique and non-transferable—is the beginning of Moschella’s carefully wrought argument in favor of parents’ authority over their children’s education, and against the state’s usurpation of that authority. Parents naturally want to raise their own children (consider our dismay when infants are switched at birth), and they have a natural duty to provide nourishment, care, and schooling. Moschella knows, of course, that some children are adopted and that some families fall apart, even that some children are neglected or abused by their biological parents, but she takes her bearings by the central case, the natural family, insisting quite rightly that this ought to guide the law.

* * *

Newly appointed assistant professor of medical ethics at Columbia University, Moschella argues that the anchor of parental authority is the human good of integrity—both the moral integrity of the parents, for whom raising their children well is integral to living well, and the moral integrity of the children themselves, which is nurtured by consistent direction as they grow. Moreover, for many families the upbringing of children is guided by their religious beliefs, which parents have an independent duty to fulfill and which thus provide a further claim against state interference.

To be sure, Moschella agrees, society has an interest in the civic education of young citizens, so that they eventually support themselves as productive members of society and are alert to do their civic duty, first and foremost by obeying the law. But this interest ought to override parental authority only in cases of abuse or neglect, she insists. Whether parents choose public schools, charter schools, religious schools, private schools, or homeschooling, Moschella is convinced that at least through the age of maturity, any education that provides basic academic and moral instruction will prepare the young for their civic responsibilities. She objects to disciples of liberal philosopher John Rawls who demand that the state inculcate respect for rights as they define them and tolerance for various ways of life. Rawlsian criteria—ostensibly intended to protect diversity by restricting people from imposing their values on others—would be deployed by the liberal state to mandate a curriculum that actually reduces diversity, something its advocates concede. What’s more, learning non-judgmentalism is neither necessary nor sufficient to making good citizens. It is possible to “teach the values of democratic deliberation based on Biblical norms” rather than Rawlsian reason, Moschella argues, offering Mother Teresa as an example.

* * *

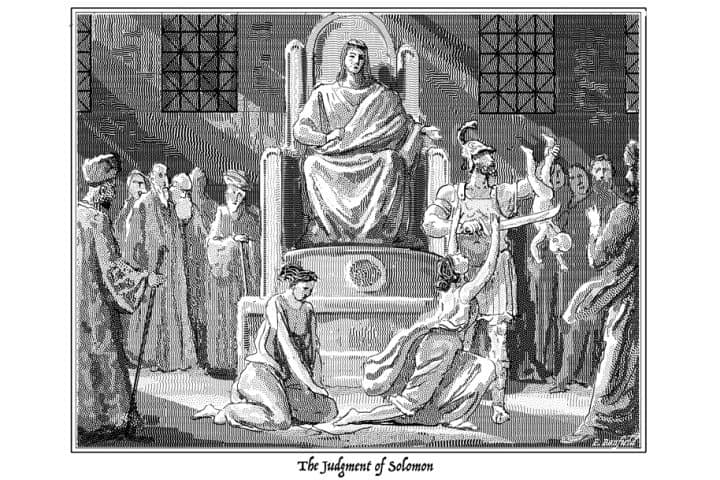

Nor are state mandates defensible for the sake of promoting children’s autonomy. Justice William Douglas expressed this concern in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972): children raised with limited access to public schools would not be exposed to all the opportunities afforded by a liberal society and therefore not equipped to choose among them. In one of her most persuasive passages, Moschella offers “[a]n Aristotelian account of the moral prerequisites for autonomy,” in which, drawing not only on Aristotle’s Ethics but on modern child development literature as well as recent discoveries in adolescent neuroscience, she argues that genuine autonomy depends upon cultivating moral virtue, the ability to resist impulses and to act thoughtfully, weighing the consequences of one’s choices. Because moral virtue is formed by instruction and habit and is cultivated slowly by repeated effort under critical eyes, she concludes that “the firm and consistent exercise of parental authority is important for the well-being of children all the way until adulthood.”

By contrast, mandatory “autonomy education,” which urges the young to view critically the values they have been taught by their parents in order to weigh them against others’—particularly others who are more indulgent to their impulses than their parents are—confuses rather than enlightens most adolescents, making them less rather than more likely to develop the strong character needed for autonomous choice. To confirm her argument, Moschella cites Religious Upbringing and the Costs of Freedom: Personal and Philosophical Essays, edited by Peter Caws and Stefani Jones (2010), a book of recollections by liberal moral philosophers about their own more authoritarian childhoods, which, far from showing that such upbringing is fatal to autonomy, even suggests that, paradoxically, authority forms the sort of strong individuals who are capable of resisting it.

* * *

As the reader must have surmised, Moschella’s book is an extended argument to undergird the right of parents to homeschool their children and the desirability of a public policy of school choice. Although she has good things to say about authoritative—if not always authoritarian—families, the premises and conclusions of her argument are liberal, in the older sense: she begins from the duties of parents to their own children and derives from these duties parental rights to decide upon their offspring’s education. Though she notes approvingly at the outset Thomas Aquinas’s denunciation of any attempt to baptize children against their parents’ desire, most of the argument is more harmonious with John Locke than with Aristotle. She endorses the Supreme Court’s decision in Wisconsin v. Yoder, which allowed Amish parents to give their children an alternative practical education on the farm during high school; decries as a matter of policy the circuit court’s decision in Mozert v. Hawkins (1987), which refused to honor evangelical parents’ request to exempt their children from readings they thought endorsed alternative ways of life; and despairs along with the imagined single mother in the Bronx whose 12-year-old daughter is taught about oral and anal sexual practices in the city’s mandatory sex-ed program at school.

In this review I have leapt over Moschella’s technical discussion of her first premises (in the introduction) as over a moat, and I recommend impatient readers do the same, as there is much they will find valuable in the subsequent theory as it stands. Still, writing as a philosopher for philosophers, she is obliged to ground her theory, which she does in the “new natural law” developed by Oxford’s John Finnis and his collaborators and students. Although it follows in the Aristotelian and Thomistic tradition, the “new natural law” nevertheless admits the “naturalistic fallacy” in that tradition of jumping from observations about the way things are to conclusions about how human beings ought to act.

* * *

This is not the place to engage the new natural law, but To Whom Do Children Belong? raises the question of its limits, precisely because the relation between parents and children is surely natural as Moschella describes it, and the “oughts” of parental care and instruction seem to follow from the fact of procreation. But if this is so, then her brief for school choice may unravel (except insofar as it is prudential), because the natural community of the family points beyond itself to the naturalness of the political community, which might in turn have a duty of moral instruction based on its understanding of the human good, insisting on teaching, not merely toleration, self-control, and prudence, but courage and justice as well. Moreover, if nature matters, then one cannot avoid, as Moschella does throughout, the question of whether the education of boys and girls should be the same—or the role of mothers and fathers in education, for that matter. After all, it is fathers’ failure to control their sons which Aristotle cites in the concluding pages of the Ethics as proof of the need for a Politics.