Books Reviewed

Citizens United v. FEC (2010) affirmed the First Amendment right of corporations to spend money on behalf of political candidates. Ever since, progressive politicians and pundits have denounced it for treating corporations as persons with the same constitutional rights as individuals. UCLA law professor Adam Winkler’s new book, We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights, turns this critique on its head. Winkler explains that courts have consistently used the notion of “corporate personhood” to limit corporations’ legal rights. Because they are creations of state law, corporate “persons” have been subject to special legal restrictions. Corporations have been more successful in asserting constitutional rights when courts ignore “corporate personhood” in favor of seeing corporations as asserting the rights of their (human) shareholders.

Populists of all parties have long attacked corporations as unwelcome intruders in American life. Winkler, however, emphasizes that corporations have been with us from our colonial beginnings. Many of the original settlements, and eventually the colonies themselves, were products of corporate charters authorized by the king of England.

American colonists became accustomed to the notion that their rights and responsibilities were delineated in colonial charters, and that their relationship with their governments was voluntary and business-like. When Parliament chose to override this relationship by ruling directly from England, the colonists rebelled. Winkler makes a compelling case that American constitutional development was heavily influenced by this experience.

* * *

Winkler’s history of corporate rights will likely surprise those who only ever see anti-corporate good guys battling it out with black-hatted corporate shills. Chief Justice Roger Taney, for example—who wrote the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) opinion declaring that persons of African descent have “no rights the white man was bound to respect”—was a leading opponent of corporate rights. Decades later, the Lochner Court, often (unfairly) depicted as the handmaiden of rapacious corporations, halted the ongoing expansion of corporate rights, allowing corporations to claim property rights but denying they could claim liberty rights, such as freedom of expression or association.

As Winkler notes, the denial of corporate liberty rights provided a readily-available rationale for the Court in 1908 to deny Berea College’s challenge to a Kentucky law requiring it to segregate. The Court’s focus on Berea College’s corporate charter seems a bit pretextual, but in other circumstances anti-corporate sentiment directly benefitted segregationist forces. Though Winkler neglects the case, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) is instructive.

In Plessy, the Supreme Court upheld a Louisiana law requiring separate railroad accommodations for blacks and whites, on the grounds that the law appropriately prohibited forced integration. This is an odd way to describe a state law requiring segregation, and, as Justice John Marshall Harlan pointed out in dissent, seemed to prohibit freedom of association among train riders. This oddity is explained by resentment over railroad corporations’ economic power. Left to their own devices, many railroads, leery of segregation’s costs, would have permitted integration, “forcing” Southern whites to bow to the rules of monopolistic out-of-state corporations and involuntarily mingle with blacks on railroad cars. The Court saw the Louisiana law as a justified restriction on the power of private railroad corporations to undermine local white supremacist mores.

Counter-intuitively, though the purportedly reactionary Lochner Court denied liberty rights to corporations, the liberal New Deal and Warren Courts granted them. Once the Justices shifted their focus from property rights and federalism to freedom of speech, they had to grant corporations liberty rights to protect corporate-owned newspapers from hostile regulations, such as those imposed in the early 1930s by Louisiana Governor Huey Long.

The civil rights movement provided an additional impetus for expanding corporate rights. To protect the NAACP—a corporation—from harassment by the State of Alabama, the Court had to recognize that non-profit corporations may assert their members’ right to “expressive association.” Winkler doesn’t mention it, but concerns about freedom of speech and civil rights coalesced when the Warren Court, in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), held that the Constitution protected the Times from an Alabama libel lawsuit motivated by hostility to the Times’s civil rights coverage.

* * *

Winkler wrote We the Corporations for a popular audience. He therefore spends much of the book depicting the often-colorful backgrounds of various individuals who played major roles in the battle over corporate rights. Whether this is a sound choice is a matter of taste. Some may find these descriptions liven a dull subject; others, like this reviewer, might find them trivial and distracting. Consider the following representative example: “As he took the stand in the Aldermanic Chamber of City Hall, the slender George Perkins, with his youthful, innocent face and hair neatly parted in the middle like a schoolboy, appeared no match for the tall, broad-shouldered, stern-looking lead investigator for the Armstrong Committee, Charles Evans Hughes.”

I would be more tolerant of these descriptive detours if Winkler’s legal analysis were more thorough and meticulous, as should be expected from a 400-page tome by a law professor. Though I don’t have any significant reservations about the general trustworthiness of the book, I did notice a lack of precision in his discussion of case precedents.

One of the book’s important themes is that businesses, blessed with the resources to pursue novel legal theories through top lawyers, are often pioneers in establishing constitutional rights that also apply to individuals. Winkler cites Allgeyer v. Louisiana (1897), which he rates one of the most important Supreme Court cases because it established the right to liberty of contract, and was a “groundbreaking precedent” for protecting other unenumerated liberty rights under the 14th Amendment’s due process clause. At best, this is exaggerated. The Court first asserted a generalized right to liberty of contract two years earlier, in Frisbie v. United States, not in Allgeyer. Allgeyer’s holding, meanwhile, established only the narrow proposition that a resident of one state has the right to contract with parties residing in another state without undue interference by his own state. And the Supreme Court made no significant progress on protecting unenumerated rights beyond liberty of contract until Meyer v. Nebraska (1923), by which time Allgeyer was relied upon only as one of 14 cases in a string citation to relevant precedents.

* * *

Moving forward over a century, Winkler treats Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc.’s (2014) holding that a closely-held corporation may claim free exercise of religion rights as a significant innovation. In 1961, however, the Court ruled on a free exercise challenge by Crown Kosher Supermarket, a corporation owned by Orthodox Jews, to a law requiring that stores be closed on Sunday. Although the Court rejected the free exercise claim by a vote of 6 to 3, none of the Justices objected to a closely-held corporation claiming free exercise rights. Hobby Lobby was controversial because it involved a corporation owned by conservative Christians challenging Obamacare birth control mandates, which pushed various ideological buttons on the left, not because it was unprecedented for the Supreme Court to permit corporations to assert free exercise rights.

Winkler also fails to reckon with the incorporation doctrine’s importance in the development of corporate rights. This doctrine, which developed in the middle of the 20th century, holds that the 14th Amendment’s due process clause protects almost all rights delineated in the Bill of Rights against the states, and that these rights are interpreted the same way against states as against the federal government. As a result, when a state law restricting corporate speech is at issue, in practice the Court is interpreting the First Amendment’s right to freedom of speech, not the 14th Amendment’s due process clause—and as a textual matter, it’s far easier to justify the regulation of corporate speech as not depriving anyone of liberty under the due process clause than to explain how it fails to infringe upon the freedom of speech protected by the First Amendment.

We the Corporations is not an ideological tract, but Winkler repeats standard—and dubious—progressive historiography as fact. For example, he regurgitates progressive dogma about the evils of late 19th-century trusts, ignoring several decades of public-choice economics literature that casts significant doubt on that narrative. He also endorses the notion that state competition in creating corporate law creates a “race to the bottom,” as if this view is uncontroversial. Many corporate law scholars, on the contrary, believe such interstate competition is a healthy process that encourages efficient rule-making.

* * *

Winkler wildly overemphasizes the significance of one of the great bogeymen of the modern American Left, the so-called “Powell Memo.” In 1971, future Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell, who was then a lawyer in private practice, urged the American corporate community to organize a legal and political defense against the increasingly assertive regulatory state. Given the increased power of federal agencies, the rise of left-wing “consumer” groups, and the growth of the lawsuit industry (thanks to various legal innovations that encouraged lucrative lawsuits against corporations), increased political assertiveness by corporate America was inevitable, with or without Powell.

Winkler confuses pro-free market organizations founded in the 1970s, such as the Cato Institute and the Heritage Foundation, with pro-corporate flack. This conflation of corporate interest with free markets raises a broader conceptual issue. Any given corporation’s interest can lie in either more or less government regulation, depending on the circumstances. An American steel company may support tariffs to protect its product from foreign competition, and an automobile manufacturer oppose those same tariffs if it can produce cars more cheaply with foreign steel. The widely diverse interests of corporations, depending on location, size, industry, and so on, provide an important reason that “corporate” political influence is frequently exaggerated—the influence of one corporate interest group is often counterbalanced by another with opposing interests. We the Corporations neglects this dynamic, instead implicitly adopting the premise that corporations have a uniform interest in less regulation.

* * *

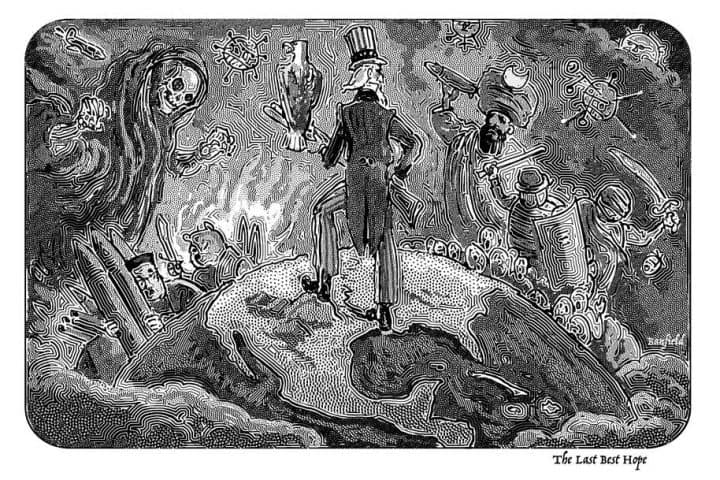

As the continuing hullabaloo over Citizens United suggests, the most salient First Amendment controversy over corporate rights is whether and to what extent the government may limit corporate political speech. Winkler simply assumes that good-guy public interest groups, seeking campaign finance “reform,” are pitted against voracious corporate self-interest. Yet the effects of limiting campaign spending on “speech” are not politically neutral. The ideological Left controls most leading sources of influence on American public opinion, including Hollywood, the arts, mainline churches, universities, the public-school establishment, corporate bureaucracies, National Public Radio, and the three legacy news networks. One arena in which the Right competes on something like a level playing field is in raising and spending money on political causes. The desire to circumscribe the Right’s ability to appeal directly to the public surely helps explain why the Left is so keen on regulating political spending.

The Left does not, however, want the government to regulate how the New York Times spends its resources, even though, by setting the news agenda, the Times likely has had a greater influence on public opinion than all corporate political spending combined. That raises an important question for opponents of Citizens United: under what theory may the government regulate the participation of a non-media corporation in the political process, which would not allow it also to regulate the content of the Times? Answering this question has proven extremely difficult.

In We the Corporations, Adam Winkler resolved the dilemma by not even raising the question.