In Plato’s Apology, Socrates defends a group of executed Athenian admirals as an example of why his justice is more reasonable than mob justice. Even though the admirals won a major victory over the Spartans, they failed to retrieve the bodies of Athenian sailors lost at sea. As punishment, the city put the admirals to death. In upholding the law and justice, Socrates pitted his reason against the Athenians’ irrational attachment to their sailors’ corpses. Similarly, he maintained that the universal justice of political philosophy would defend his particular political community, opposing the sort of irrational practices that had built up in Athens over time.

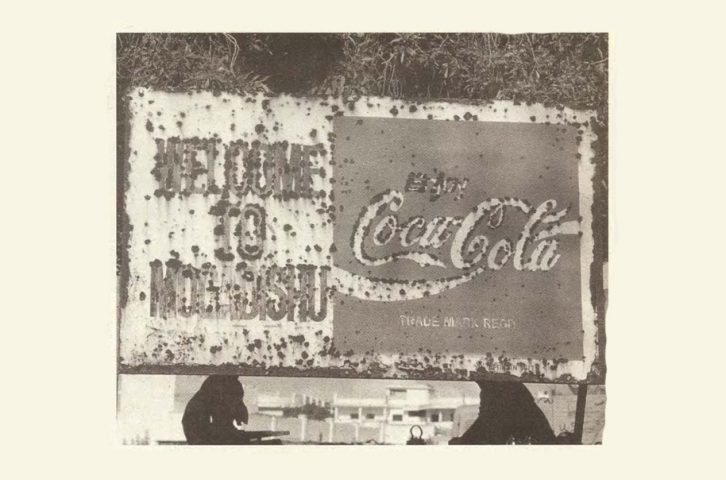

Opening with a quotation from Plato on war, Ridley Scott’s “Black Hawk Down” depicts the U.S.-led effort in 1993 to impose order in a Somalia beset by famine and civil war. This specific episode of that little war seems to defy all reason. What was supposed to be a 30-minute hit-and-run raid to capture a warlord’s lieutenants became a hellacious 17-hour firefight. The recovery of the bodies of fallen U.S. Army Rangers and Black Hawk helicopter pilots motivates a great portion of the action in the movie—”leave no man behind” is the moral premise, supported by helicopters and high-tech weaponry. The simplicity of that ethic has nightmarish consequences. All of the West’s technological and military might is barely sufficient in the face of thousands of Kalishnikov-toting “skinnies,” as the Somalis are called by their would-be protectors.

It should have been a one-sided fight. But with the Americans’ rationalism come bureaucratic modes of battle-fighting under preposterous rules of engagement; a preference for shows of force over use of force, the commitment to international peace-keeping; and the Clinton Administration’s obsession with “nation-building.” These even the skinnies’ odds considerably. Even Somali children know they can ridicule the American warriors.

While Americans curse their fate and babble bureaucratically, the most sophisticated character in the movie may be the Somali interrogator of a downed American helicopter pilot. When the American turns down the offer of a cigarette, the Somali remarks that of course Americans no longer smoke; they would rather live long and boring lives. The interrogator observes that even though the pilot is authorized to make war, he cannot negotiate. In Somalia, war is negotiation. He then reflects that Americans don’t belong there—it’s a Somali matter. His urbanity contrasts with the naïveté of the American discussion of the war, seen at the beginning of the film.

Americans exhibit their faults—braggadocio, superficiality, arrogance, sentimentality: The upper echelon of the military is a helpless bureaucracy, anesthetized from the battlefield’s “fog of war” and “friction.” These make the cunning and courage of the soldiers on the ground and in the air all the more credible, and necessary. We are driven from the comforts of technology to the reality of the body. We see the bodies shot, blown in half, mangled.

Like “Saving Private Ryan,” “Black Hawk Down” drains the viewer. This movie about claiming bodies claims our body. Ridley Scott beats us into submission.

But the patriotism of “Private Ryan,” with its thrusting of obligation upon us, is not present in “Black Hawk Down.” It combines the virtues of that unappreciated Vietnam movie, “Go Tell the Spartans,” and of the better-known “Zulu.” Like Scott’s best film, “Bladerunner,” it examines how men can overcome overwhelming odds to preserve themselves—whether against machines or against skinnies. As in “Gladiator,” we must fight to preserve our humanity. Both films reveal the manly qualities, if not ruthlessness, required to preserve not merely life but a life worth living.

The West may boast of its rationality, its technology, and its efficiency. But it requires the raw courage of warriors to save its humanity. This is why Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg honored the fallen—for “the cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion.”

The fundamental difference between peoples lies in their regimes, the principles by which they live. The American regime requires reason, for we are a nation whose fundamental principle is the rational, self-evident truth of human equality. The lesson of “Black Hawk Down” is that without a proper understanding of that truth, we will become just like the “skinnies.”

* * *

The power and the radical limitations of the attenuated, Cartesian notion of human reason are vividly displayed in “A Beautiful Mind,” which stars “Gladiator”‘s Russell Crowe as economist and code-breaker John Nash. We see a man’s attempt to mathematize the universe. But, in fact, the political needs of post-World War II America dominate Nash’s life. Striving to reconcile the mathematical with the political, he goes mad. But love saves the disturbed economist who will later win the Nobel Prize. That the nerdish Nash could be played so well by “Maximus” Crowe shows how great and versatile an actor he really is.

* * *

Writers, however secular they may be, often make elaborate use of religious motifs. For example, Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Remains of the Day” (the film is a weak image of the novel) describes a kind of reverse Canterbury pilgrimage of a butler who drives west across England and talks to himself, seemingly uncomprehendingly, about his vacuous life. But does the pointed absence of religion mean that a religious resolution is being limned, emerging from the shadows, chiaroscuro-like? A more recent case, “American Beauty,” was merely a boring diatribe against the American middle-class, unless one takes seriously the Christian symbols. But what is the producer-director’s intent? One would have to take seriously the notion that the symbols of religion have a power of their own, and hence, they are not mere symbols.

One should keep this possibility in mind while enjoying Joel and Ethan Coen’s latest movie, “The Man Who Wasn’t There.” We see scam after scam, deceiving believers, spouses, juries, business partners, the nation. Any emotional attachment represents a possibility for exploitation. A priest appears to be raising the Host, which turns out to be a bingo number. The featured two-man barbershop has a trinity of chairs that is noted but never explained. As in other Coen brothers films (e.g., “Miller’s Crossing”), religious allusions abound. The resigned, purposeless life led by the barber-protagonist, played by Billy Bob Thornton, reminds us of Albert Camus’s “The Stranger.” Is the real “man who wasn’t there” Jesus Christ? Their previous film, “Oh Brother, Where Art Thou,” is loosely based on the Odyssey—while lacking Odysseus’s son, Telemachus. In that film, the New Deal and rural electrification appear to take the place of God. But what is the purpose of the recalling of religion, other than to tease and mock the audience? Could it be that the Coen brothers are fooling themselves?