Books Reviewed

Has law become the enemy of liberty in 21st-century America? Most people will bridle at the suggestion; those on the Left will recall the role of law in liberating African-Americans after 1954, while those on the Right will think of the mighty contributions to liberty deriving from legal protections of property and contract. But those on either side who seriously attend to this provocative little book might just change their minds.

Philip Howard is a partner at Covington and Burling, active in civic organizations in New York City, and a self-described “legal reformer” whose observations on the ever-expanding legal imperium have appeared on many op-ed pages. His previous book, The Death of Common Sense (1995), demonstrated powerfully that the substitution of “process” for human judgment in the law is causing profoundly irrational social effects.

In this new book, Howard covers some familiar ground. He attacks the extension of tort liability in recent decades (ever more “creative” notions of who can sue whom for what), and the frequent capriciousness of damage awards wrung from pliant juries. He also addresses the unceasing creation of new individual rights (both rights against government and rights against other individuals); he laments (again) the proliferation of procedural requirements and constraints that render effective leadership and the pursuit of excellence increasingly difficult in both public and private institutions. But what makes the book much better than its predecessor is not the hair-raising series of examples he presents, but rather his perceptive accounting of the costs of all this, of what is lost by the encroachment of too much law into too many aspects of our lives. What is lost is liberty.

Discussing the plague of preposterous lawsuits that has descended on our land, for instance, Howard highlights the case of a “volunteer for the Legion of Mary in Milwaukee, delivering a statue of the Virgin Mary to an ill parishioner.” The unfortunate volunteer ran a red light and caused an accident seriously injuring the other driver, an 82-year-old man. The victim, “in search of a deep pocket, sued the Catholic Arch-Diocese of Milwaukee,” claiming it was liable for the acts of all volunteers, even in remotely affiliated organizations. Without a word (apparently without a thought) about the larger social implications of such galloping liability (an old lady bringing a casserole to church supper?) the judge sent the case to the jury that returned $17 million in damages. “[L]awsuits in America,” Howard concludes, “are limited mainly by the imagination of the lawyers.” But then he takes account of the “liberty costs” of legal incontinence, quoting former Harvard president Derek Bok’s observation that lawsuits “often have their greatest effect on people who are neither parties to the litigation nor aware it is going on.” It is fear of being sued that causes people (towns, public officials, businessmen, teachers) to forgo their freedom to choose— “to do what they think is right…where there’s even the slightest possibility someone might have a different view.” The point is that “[w]hat people can sue for is a key marker defining the scope of free activity.” Ever expanding notions of liability resonate and reverberate through society. People become reflexively defensive, pulling in their horns, covering their backsides, and progressively forfeiting their liberty.

* * *

Howard’s chapters on the “legalization” of the schools are equally devastating. He cites a study of all the legal rules imposed on a high school in New York City. The inventory found “thousands of discrete legal requirements imposed by every level of government.” Of course, rules are sometimes desirable—no one celebrates the exercise of unbridled power by those in positions of authority—but what is sacrificed to a plethora of rules is the leader’s capacity to exercise judgment, the indispensable quality that sustains success and satisfaction in all human (or humane) endeavors. It is precisely liberty to pursue excellence that is imperiled by reflexive legalizing. Howard reminds us that in certain important ways rules are also the enemy of justice. Justice involves a subtle fitting of disposition to the case at hand, employing a number of criteria which cannot all be specified in advance, which may themselves be in tension, and which are not susceptible to rank ordering. Law, by contrast, involves specifying certain gross aspects of human situations and treating these alone as decisive. Rules are mindless, undiscriminating things. They cannot be inflected to pick up the variety—the differentness—of situations without sacrificing the one, sometimes valuable, thing they can deliver, uniformity of outcomes.

The proliferation of rules is closely related, of course, to the catastrophic breakdown of discipline in public schools. Howard invokes Professor Richard Arum, who concluded in Judging School Discipline: The Crisis of Moral Authority (2005) that “[t]he decline of order…is directly tied to the rise of ‘due process.'” Judicially mandated due process standards, and the cumbersome special education strictures embodied in legislation such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, have made the liberties of students, teachers, and administrators increasingly captive to the most disturbed and disruptive pupils (and their parents and lawyers).

Howard understands the liberty issues involved because he properly understands that liberty is a binary concept. It has both an individual and a corporate dimension; it includes not only individual rights against government and against other individuals, but self-government—the capacity of groups of people to order significant aspects of their communities and institutions according to their own lights without external direction or control. This is what historian Herman Belz meant when he wrote some years ago of “the idea of self-government which defines American nationality—that is citizens governing themselves as individuals in local communities and private associations.” To enjoy liberty in this sense people must be able to choose leaders who can actually lead, who are not progressively disabled by a thousand strands of lawyerly restraint.

The march of legalization has pounded through all American institutions (think of doctors over-prescribing). Remember General Tommy Franks, focused on a screen showing the Mullah Omar’s car, framed in cross-hairs, racing out of Kabul, with an air controller in Arizona ready to pull the trigger, when Central Command’s JAG officer opines that doing so might violate a Ford-era executive order banning assassinations of heads of state. Anyone who doesn’t think that lawyers are increasingly influential in American councils of war hasn’t been paying attention.

* * *

How did this happen to us? How did the law, historically the guarantor of our liberties, come so to overpower us and infantilize us? Here, Howard is not so helpful. He has written a fierce polemic and polemics are not long on explanations, yet an explanation we must have if we are to combat the malady effectively. Howard does take a first step when he writes that:

In the heyday of the rights revolution, in the 1960s and 1970s, the Supreme Court expanded the reach of the due process clause to personnel decisions for public employees. The basic idea is that competence can be proved in a legal hearing.

Well, the Court did that and much, much more. In Goldberg v. Kelly (1970), the Justices extended due process to administrative decisions to terminate welfare benefits, and in Goss v. Lopez (1975), the Court insisted on due process for even mild school punishments such as suspensions. The litany of Warren and later Supreme Court rights creation is long, complicated, and fills a five-foot shelf of books. But what is only now coming into sharp focus is how the Court’s rights revolution reverberated throughout American society. Private institutions, especially universities and other non-profits, rushed to legalize their own internal operations, emulating the models of “fairness” on display in the public sector. Private employers rushed to promulgate cumbersome, liberty-restricting rule books to protect themselves against complaints that they were insufficiently attentive to affirmative action or sexual harassment. So, the rights revolution, largely but not completely judicially driven (e.g., the Americans with Disabilities Act), drove contemporary hyper-legalization.

But what drove the rights revolution?

The answer to that, bringing us finally to the heart of the matter, is the consuming preoccupation with equality of condition that has been the intellectual hallmark of American elites over the last half century. It was this—that ever-so-visible inequality between the sympathetic injured plaintiff and the big public sector or private sector defendant—that fueled not only the Court’s rights revolution, but also the vaulting expansion of tort liability with ever more attenuated theories inserting plaintiffs’ lawyers’ hands into deep pockets. So what if the attribution of fault to the defendant is implausible—help out the little guy! The same egalitarian logic seeks to grind down all asymmetries of power. That is why we legally Gulliverize authority figures with a hobbling latticework of rules, because legalizing is thought to reduce what we are now taught to believe are the terrible dangers lurking in unequal relationships.

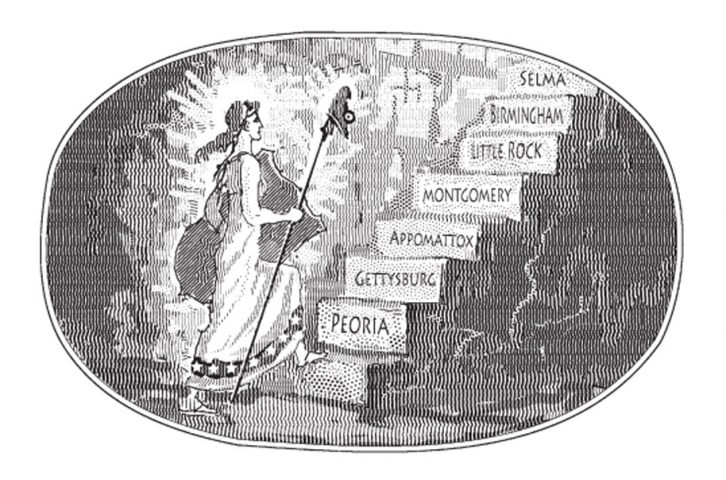

This stands the American political tradition on its head. For the revolutionary, founding, and formative generations, the purpose of government was to protect individual liberty, and tyranny occurred when government interfered with the kinds of individual and private group choices it was established to protect. This describes just as well the generation that won the Civil War and framed the 14th amendment. Of course, they were concerned with equality, but it was equality in the sense of equal liberty. Equality thus understood did not threaten liberty in the American intellectual and constitutional architecture, it enhanced it. The inherent tension between equality and liberty was a fruitful one. Ours was a liberal notion of equality, which responded temperately to the leveling impulse that had been part of Anglo-American political thought since the English Revolution.

In retrospect we can see how a misunderstanding of the idea of equality achieved a sudden ascendency in the political imagination of Americans after 1960. Righting the great national wrong done to black people was imperative and inspiring, and equality was seen somehow to be at the center of that. But now, in the age of Obama, it is necessary to return to our intellectual roots, and to remember that it was not equality under despotism that the American revolutionaries fought for, but equality in liberty. Among many other good things, remembering this will arm us to resist the hyper-legalization that so burdens and diminishes our liberty today.