Discussed in this Essay

When The Wire first aired on HBO in June 2002, I took a quick look and decided not to bother with a foul-mouthed TV series about cynical cops chasing violent drug dealers in the depressed black neighborhoods of West Baltimore. For one thing, I knew enough about commercialized rap music that I did not wish to join the vast pale-faced audience for a new brand of minstrelsy more exploitative than the old. And I was doubtless influenced by the fact that the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, had pushed inner-city poverty, social dysfunction, and misdirected policing off the national agenda.

The blight affecting the ghetto poor stayed off the agenda for a decade, as Americans fought two agonizing wars in the Middle East, got whacked by the financial crisis, and became enraged by political paralysis in Washington. It might still be off the agenda if the invention of the smartphone camera had not forced it back on. Unfortunately, being on the national agenda is now a liability, as cable “news” and “social” media whip every disagreement into a screaming match, if not an armed confrontation. The Russian operatives stoking the disinformation flames must be proud. But the fact is, we don’t need their help burning down our own house while accusing one another of arson.

The Wire was not a hit back in 2002, but it attracted a loyal audience and enough critical praise to get renewed for a second season, followed by three more. By the time Season Five ended in March 2008, it was routinely ranked as one of the best TV series of all time, and millions of fans were discovering the joys of watching a long, intricate series on DVD, as opposed to in weekly installments on cable. Today we can stream The Wire, and urged by certain wise heads of my acquaintance, I have now binged my way through all five seasons. The wise heads were right: it is a masterpiece.

Not a Hollywood masterpiece, mind you. The Wire was created by David Simon, who grew up in Bethesda, Maryland, and spent 13 years as a crime reporter for the Baltimore Sun; and Edward P. Burns, a Baltimore native and Vietnam veteran who spent 20 years as a homicide detective for the Baltimore Police Department, followed by seven years teaching in one of the city’s dysfunctional public schools. As Simon told the British writer Nick Hornby in 2007, “Our impulses are all the natural reactions of writers who live in close proximity to a specific American experience—independent of Hollywood.”

Simon has given hundreds of interviews on an ever-lengthening list of topics. As far as I can tell, Burns gave one short one with HBO in 2007, about his teaching experience. To be tactful about it: some people let success and fame go to their heads; others do not. Still, when Simon is not making sweeping pronouncements about world-historical issues, he speaks insightfully about his own work. In that same 2007 interview with Hornby, he made this canny observation:

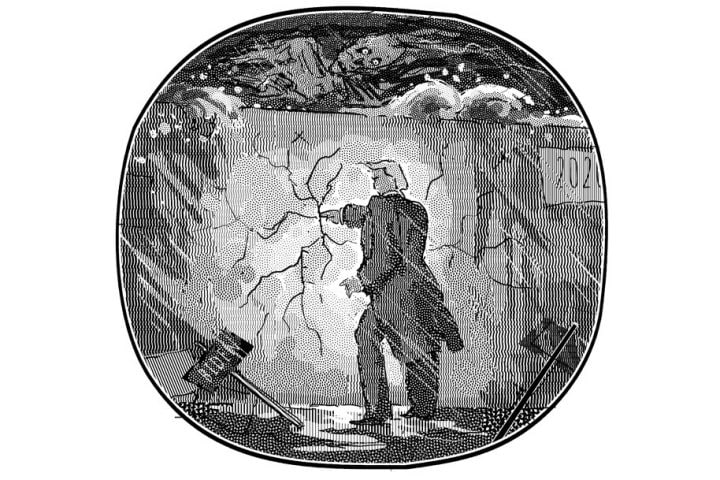

We’re…lifting our thematic stance wholesale from Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides to create doomed and fated protagonists who confront a rigged game and their own mortality…. But instead of the old gods, The Wire is a Greek tragedy in which the postmodern institutions are the Olympian forces. It’s the police department, or the drug economy, or the political structures, or the school administration, or the macroeconomic forces that are throwing the lightning bolts and hitting people in the ass for no decent reason.

Simon is wrong about Zeus hurling random lightning bolts at people; that was not the god’s style. And Simon confuses the Olympian gods with the Fates, or Moirai, ancient female deities who spin the thread of each human life, measure it out, and (when the time comes) cut it. But Simon is right about the general tendency of the Greek gods to kick back with some nectar and ambrosia and watch the strife and misery of human existence with a certain blithe indifference.

Fair-Minded Storytelling

To be honest, there is an element of blithe indifference in the way millions of Americans watch The Wire’s depiction of entrenched poverty, family dysfunction, drug addiction, and social isolation among “the truly disadvantaged,” to use the term coined 33 years ago by sociologist William Julius Wilson. But contrary to my suspicion back in 2002, The Wire doesn’t cater to the audience’s voyeuristic tendencies. It is far too demanding—and far too grounded in the lived experience, not just of Simon and Burns but of several cast and crew members, as well as the city residents and officials who greased the wheels of this five-year production. (Advice to non-native speakers of either white working-class or black inner-city Bawlmerese: turn on the English subtitles!)

Thanks to the critical race theorists of the 1980s, lived experience (“experiential knowledge”) is now a weapon in the culture war against reasoned analysis (“epistemic oppression”). This is unfortunate, because lived experience is essential, not as a replacement for reasoned analysis but as a rudder to steer it away from easy ideological answers and toward hard real-world questions.

We see this in the career of the aforementioned Professor Wilson, one of the few social scientists to include economic, social, political, and cultural factors in his lifelong study of the ghetto poor. As he remarked on a panel at the Brookings Institution in 2017, “[T]oo many liberal social scientists focus on social structure and ignore cultural conditions [and]…[t]oo many conservatives focus on cultural forces and ignore structural factors.” This fair-mindedness may stem in part from Wilson’s lived experience as the son of a coal miner in western Pennsylvania who died of lung disease at 39, leaving his widow to support their six children by cleaning houses. “What I distinctly remember,” he told the panel, “is hunger.”

In a similar way, the word “narrative” has been weaponized to mean politically tendentious retellings of history. This, too, is unfortunate, because without fair-minded storytelling, it is very difficult to teach complex subjects to the young. This is why Wilson included The Wire in a course he and Jeremy Levine co-taught at Harvard on “urban inequality.” The course was denounced in the Boston Globe by satirist Ishmael Reed, who accused Wilson and Levine (not by name) of teaching “hot courses built around sensational popular culture like hip-hop and crime shows as a way of filling seats in their classrooms.”

A glance at Wilson’s syllabus reveals how badly that barb missed its mark. All five seasons of The Wire are assigned in sequence, alongside a demanding and ideologically diverse reading list. The idea, argued Wilson in a 2010 op-ed for the Washington Post, was to put flesh on the bones of social science by dramatizing how economic, social, political, and cultural forces constrain the choices of an array of vivid and memorable characters: addicts shooting up in abandoned row houses, “corner boys” getting roughed up by police, hard-eyed “soldiers” in the drug game killing rivals and snitches, jaded cops “juking the stats” to game the system, resolute detectives trying to solve multiple murders, desperate dockworkers watching their jobs disappear, drug kingpins dreaming of respect and legitimacy, embattled teachers struggling to educate students while “teaching to the test,” and honest newspaper editors trying to uphold standards while hemorrhaging readers.

It’s easy to imagine a different TV series showing the same forces determining the fates of un-vivid, un-memorable characters while pushing a political message at every turn. This is called propaganda, and authoritarian regimes are not the only ones grinding it out like sausage. Perhaps the most crucial difference between propaganda and genuine storytelling is the role of moral agency. When Simon says that his “doomed and fated protagonists…confront a rigged game,” the word “confront” suggests a modicum of free will. Wilson puts it more strongly, writing that certain “circumstances…govern our lives—despite our best efforts to demonstrate our individual autonomy, distinctiveness, and moral and material worth” (emphasis added).

A Tragic Downfall

True determinism is hard to defend philosophically, and even harder to work into art. As noted by Aristotle in the Poetics, the most important element in tragedy is not character but plot—because plot is action, and character is revealed only through action. By action, Aristotle did not mean car chases and explosions (he would have classified these as spectacle, the least important of the six dramatic elements). What he meant was moral agency. Today, we use the word “tragedy” whenever people are brought low by circumstances beyond their control. In that sense, The Wire is chock-full of tragic figures. But if we go by Aristotle’s definition of a tragic hero as an “intermediate kind of personage, a man not pre-eminently virtuous and just, whose misfortune, however, is brought upon him not by vice and depravity but by some error of judgment,” then the series has only a few. Of these, the most poignant is Preston “Bodie” Broadus, played with eloquent understatement by J.D. Williams.

Like most of the characters in The Wire, Bodie is not prepossessing at first. We initially encounter him as a hunched figure in a navy blue hoodie, seated on a discarded orange sofa in the courtyard of a low-rise public housing project known as “the Pit,” with a permanent scowl on his face. At age 16 Bodie is a mid-level manager in the drug organization headed by Avon Barksdale (Wood Harris). Bodie does not respect his new boss, Avon’s nephew with the curious first name of D’Angelo (Larry Gilliard, Jr.). He is impatient with the young “hoppers” who perform the transactions. And he is contemptuous of the junkies shuffling up for their next fix. It slowly emerges that Bodie has reason to find fault with others: he is braver and smarter than most of the people around him, including the police.

Bodie never knew his father, and his mother overdosed when he was four, leaving him in the care of his grandmother (Caroline G. Pleasant). One criticism I would make of The Wire is its neglect of the older people, especially the women, who strive 24/7 to protect the young against the ravages of the ghetto environment. Bodie’s grandmother is on the screen for less than five minutes. If you blink you will miss her. But she has clearly given her grandson a steadiness and strength to match his intelligence.

In episode three of Season One, Bodie and a boyhood friend and fellow dealer named Wallace (played by Michael B. Jordan) are playing checkers with a chess set, when D’Angelo stops by and insists on teaching them the “much better game” of chess. The scene is bittersweet, because Bodie and Wallace are quick to see the connection between the “little bald-headed bitches,” or pawns, and their own place in the drug trade, a.k.a. “the Game.” Learning that pawns can only move one square forward except when capturing another piece or “the other dude’s king,” Bodie muses: “So if I make it to the end, then I’m top dog?” D’Angelo corrects him: “Yo, it ain’t like that. The pawns, man, in the game, they get capped quick. They be out the game early.” With one of his rare smiles, Bodie says, “Unless they some smart-ass pawns.”

But here we see the error that sets Bodie’s misfortune in motion. Strong, smart-ass Bodie catches the eye of Avon Barksdale’s second-in-command, Stringer Bell (Idris Elba) and, gratified by the older man’s attention, reluctantly agrees to execute Wallace for having informed on the gang. When the moment comes, Bodie falters, and it is only through the intervention of another boyhood friend and dealer, Poot (Tray Chaney), that the tender-hearted Wallace is cut down.

To trace Bodie’s fate is to deplore the waste of a life. But it is also to detect a tragic hero. In episode 13 of Season Four, Bodie meets with Detective McNulty (Dominic West), the only police officer he has ever come close to trusting, in Cylburn Arboretum, a beautiful leafy park that Bodie is surprised to learn is part of Baltimore. Bodie feels betrayed by Marlo Stanfield (Jamie Hector), a newly established gang leader who ruthlessly orders the deaths of everyone who looks at him sideways. So McNulty, who typically uses up all the oxygen in the room, keeps his mouth admirably shut while Bodie makes what may be the longest speech of his life:

I ain’t no snitch. I been doing this a long time…. I ain’t never talked to no cop…. I feel old. I been out there since I was thirteen. I ain’t never f–ked up on a count, ain’t never stole off a package, never did some shit that I wasn’t told to do. I been straight up. But what come back? You’d think if I got jammed up in some shit they’d be like, “All right. Yeah. Bodie been there. Bodie hang tough. We got his pay lawyer, we got a bail.” They want me to stand with them, right? But where the f–k they at when they supposed to be standing by us? I mean, when the shit goes bad and there’s hell to pay, where they at?

Bodie has no intention of informing on his corner boys or the remnants of the Barksdale gang. “But Marlo, this n–ga and his kind? They gotta fall. They gotta.” To McNulty’s warning, “For that to happen, somebody’s gotta step up,” Bodie replies, “I do what I gotta. I don’t give a f–k! Just don’t ask me to live on my f–king knees.” McNulty remarks quietly, “You’re a soldier, Bodie.” And Bodie says, “Hell, yeah.”

By informing on Marlo, Bodie signs his own death warrant. He also makes it possible for McNulty and his fellow detectives to solve a score of cold-case murders—although by pointing this out, I realize I am going against the consensus of a large portion of the pale-faced commentariat, for whom The Wire is a masterpiece precisely because it offers no hope. As one celebrity thinker, British philosopher John Gray, expressed it in 2012, “[O]ne of the show’s greatest achievements” is that it “presents a damning portrait of inner-city life in America without the prospect of redemption.”

My response to this is simple: what about Bubbles?

A Lost Soul Redeemed

Of all the misery on display in The Wire, the most affecting is that of the heroin addict Reginald “Bubbles” Cousins. In an extraordinary performance by Andre Royo, Bubbles makes his entrance as one of the pathetic homeless figures one sees sleeping in doorways and pushing jam-packed shopping carts. Then gradually, with many stops and starts, we watch this seemingly lost soul morph into a scrappy entrepreneur, a police spy too clever to get caught, a guardian angel to two young addicts, and in Season Three, a poor man’s Dante in Hell.

This last reference is to a social experiment undertaken—without permission—by Major Howard “Bunny” Colvin (Robert Wisdom), an independent-minded police officer nearing retirement. Having lived and worked in West Baltimore his whole life, Colvin attempts to curb the ravages of the drug trade, and the war on drugs, by corralling all the dealers and users into a few abandoned blocks and telling the police to let them alone. The experiment succeeds in restoring a blessed sense of normalcy to the rest of the district. But when Bubbles crosses into one of these special “free zones,” dubbed “Hamsterdam” by a corner boy who has never heard of Amsterdam, he enters the Inferno.

It is beyond me how Simon could have created these horrific scenes while at the same time confidently asserting that the drug plague would disappear with legalization. Unlike Simon, I do not have the solution up my sleeve. But to its credit, neither does The Wire. On the night Bubbles pushes his shopping cart full of T-shirts through the firelit streets of Hamsterdam, his hawker’s call is drowned out by the calls of the dealers, and the cries of a mob of ragged, contorted shadows beating, robbing, and prostituting one another for the price of their next dose. The expression on Bubbles’s face suggests that, like Dante, he is being harrowed in his soul.

The Wire is not apolitical. While it has precious few kind words for the Democratic establishment in Baltimore, it has none for the Republicans in state government. A good friend refuses to watch The Wire because, as she says, “I don’t like being preached at.” Given the noxious virtue-signaling now pervading the culture, I don’t blame her for expecting The Wire to be about as enlightening as a CNN debate over how many woke activists can dance on the head of a pin. But here’s the thing: this series could probably not be made today. Or if it were, it would be denounced by those same woke activists for failing to toe the “progressive” party line.

For example, only once in the entire 60 hours does a police officer use deadly force. In episode nine of Season Three, a rookie cop called Prez (for Pryzbylewski), panics in a dark alley and shoots a black man who turns out to be an undercover cop. Totally inept with guns, Prez (Jim True-Frost) has proved himself as a talented breaker of codes used by the Barksdale gang. But now he must quit the force, and the next time we see him, he is struggling to teach math in a chaotic middle school.

I have never been a cop, drug dealer, dockworker, or district attorney. But I have been an inner-city schoolteacher, and of all the films and TV shows I have seen about that challenging occupation, The Wire rings the truest. I have also seen a close family member recover from addiction, and I feel the same way about Bubbles’s recovery. Those who declare The Wire to be without hope must have watched the part about Bubbles with their eyes closed, because while the tale of this downtrodden but valiant spirit does not illustrate anyone’s ideology, it does speak, poetically, of redemption.